Abstract

There is broad evidence that social connectedness is a significant factor contributing to mental health and wellbeing. Research on first responders in Australia has demonstrated that social connectedness moderates various aspects of psychological health. For first responders, social connectedness exerts a protective influence on the harmful effects of trauma exposure, such as psychological distress in the form of anxiety, depression, Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), and increased suicide risk. Furthermore, first responders’ social support, team cohesion, engagement with workplace support programs and work-life balance are all associated with higher resilience. The research also identified barriers to seeking help among first responders who may be struggling. These included poor mental health literacy, stigma and delayed help-seeking due to a lack of confidence in psychological treatments.1 These barriers increase the potential for mental health issues to develop into larger and debilitating problems that adversely affect workplace functioning and people’s quality of life.

Program description

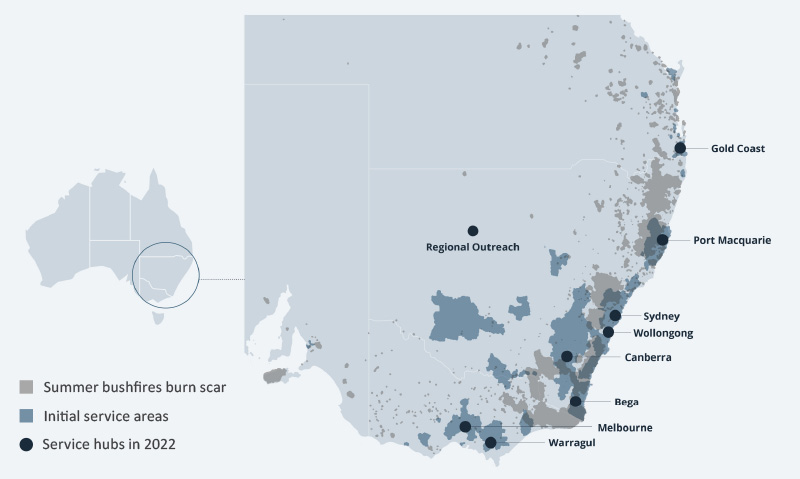

This paper presents a model of care that places the wellbeing and mental health of first responders and their families at the centre. The model is designed to help protect first responders from the negative effects of their work by improving protective factors and addressing the barriers to help-seeking identified in the research. Fortem’s programs are independent and adjunctive to other workplace programs. They are available to employees, volunteers and family members of over 30 emergency services, law enforcement and national security agencies. A core feature of the model of care has been to establish service delivery ‘on the ground’ in locations where need is greatest. This allows direct, in-person connection within specific first responder communities. This is augmented by virtual activities that extend the reach to members who are deployed overseas and has allowed continuity of service during pandemic lockdowns. Fortem has 4 service offerings suited to first responders: wellbeing programs, clinical services, mental health literacy and transition support. This paper focuses on data from the wellbeing programs and clinical services.

The social connection-focused wellbeing activities enhance resilience for first responders and also for their families. Based on evidence for the modifiable determinants of wellbeing summarised in the Royal Melbourne Hospital’s 5 Ways to Wellbeing framework2, the activities provide opportunities to build connections within families, work teams and between different first responder agencies, allowing the formation of networks of safety and support. Furthermore, through low-threat, low-stigma activities, the program engages first responders who may otherwise be unaware of the need for, or indeed actively avoid, overt attempts to address mental health concerns. These activities pave the way for early detection and early intervention for mental ill health and serve as a ‘soft entry’ into clinical services.

The wellbeing model draws on international research about the modifiable determinants of wellbeing summarised in the 5 Ways to Wellbeing framework.

Fortem’s specialist psychology services are first responder-culture-informed, confidential, accessible, independent of injury management systems and inclusive of family. Participants can access psychological support via self-referral or referral from internal agency support or other health professionals. Evidence-based psychological treatments are provided via face-to-face and telehealth consultations to maximise accessibility, especially for people in regional areas.

Service locations were established to ‘reach in’ to communities most effected by the summer bushfires.

Methods

The preliminary qualitative and quantitative data collected for study was done via routine quality assurance monitoring. Data from the wellbeing programs was derived from a sample of 975 participants in activities held between March 2020 and April 2022. For short (single day) events, post-activity surveys covered areas of engagement, satisfaction, wellbeing and mental health. Longer programs (4 weeks or more) also included standardised measures for wellbeing (Personal Wellbeing Index) and social support (Brief 2-Way Social Support Scale). The clinical services data was derived from a sample of 46 first responder employees, volunteers and family members who completed a course of treatment between December 2020 and April 2022.

The clinical services were evaluated using standardised psychometric measures administered both pre- and post-treatment. These cover mental health conditions and wellbeing constructs relevant to first responders. In choosing the measures, care was taken to balance the need to collect as much useful data as possible in key areas while also minimising the burden for participants. Measures were selected to benchmark with those used in population-level research on first responders in Australia. Additional demographic and engagement data were extracted from Fortem’s customer relationship management system.

Table 1: Standardised psychometric measures used to evaluate a range of clinical outcomes.

| Construct | Measure |

| Psychological distress | Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10) |

| PTSD | International Trauma Questionnaire (ITQ) |

| Complex PTSD | International Trauma Questionnaire (ITQ) |

| Alcohol use | Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) |

| Wellbeing | Personal Wellbeing Index (PWI-A) |

| Social support | Brief 2-Way Social Support Scale (Brief 2-WaySSS) |

| Resilience | Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale 2 (CD-RISC-2) |

Results

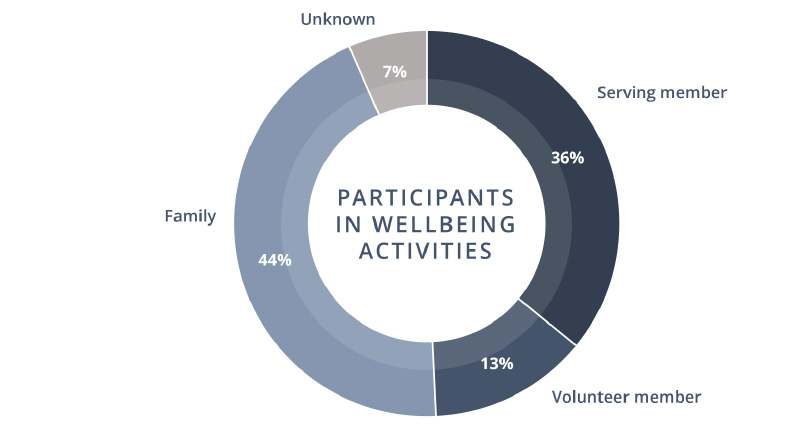

The quantitative and qualitative data from the wellbeing programs demonstrated broad engagement with wellbeing and protective lifestyle practices. Participants were employed first responders (36%), volunteers (13%) and family members (44%).

Participants reported relatively high social connectedness to family members (85% ‘well’ or ‘very well’ connected) with lower rates of connectedness to workmates (57% ‘well’ or ‘very well’ connected). Of the 5 Ways to Wellbeing, the category ‘Connect’ emerged as the way to wellbeing enhanced by a wellbeing activity by the greatest number of participants (79%). Similarly, 64% of participants indicated that they felt the activity had strengthened their social network. An overwhelming number of participants (97%) reported that an activity had benefited their health and wellbeing. Program feedback was generally very positive, with various measures of satisfaction and engagement between 89% and 91%.

Regarding attitudes towards help-seeking, a majority of participants (79%) indicated that they were either ‘likely’ or ‘extremely likely’ to seek mental health support if needed. There were some rich themes that emerged from the qualitative data that demonstrated increased awareness and engagement in behaviours that increase wellbeing. Participants indicated greater motivation to prioritise social connection and other wellbeing behaviours that were outside of their usual comfort zones.

Figure 1: Wellbeing program participants by role status

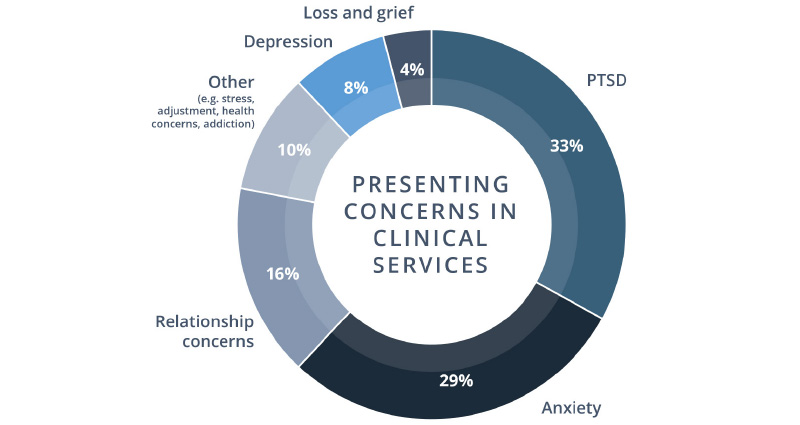

The clinical services data presented a broad story of preventative and restorative health: participants enter the service showing signs of compromised wellbeing and leave the service with this largely restored. Just over two-thirds (69%) of clinical services recipients were serving first responders, with the remainder (31%) being family members. A significant number (17%) accessed the clinical services following an experience of a wellbeing activity. The primary concerns included PTSD (33%), anxiety (29%) and relationship difficulties (16%). Feedback included:

This isn't an activity that I would have usually chosen for myself but by attending with my family… it allowed me to try something very much out of my comfort zone and help build confidence and skills. By meeting up with a colleague too it allowed us to have… time to chat and catch up too. (Survey participant response)

With regard to clinical outcomes, 80% of participants who demonstrated measurable symptoms of PTSD no longer had active PTSD symptoms after treatment.3,4 There is a related diagnosis known as Complex PTSD, which indicates a deeper and more extensive influence from multiple traumatic events and prolonged exposure to traumatic stress. Complex PTSD remains an under-recognised condition among first responders. Sixty-seven per cent of participants who had measurable symptoms of Complex PTSD no longer had active symptoms following treatment. This is encouraging as Complex PTSD can be hard to treat and generally takes longer to achieve clinically significant improvement. Psychological distress improved from ‘very high’ at intake to ‘moderate’ at discharge. This result is encouraging given research that demonstrates that first responders experience ‘substantially higher’ rates of psychological distress compared to the general population.1 At intake, the average levels of wellbeing were ‘compromised’ compared to the general population and largely restored to a ‘normal’ range by the end of treatment. Despite participants reporting relatively high levels of social support, the data indicated an increase in the sense of receiving emotional and instrumental support. Like wellbeing, the average levels of resilience were slightly compromised at intake and returned to within population norms at discharge.

Figure 2: Presenting concerns of participants seeking psychological support

Discussion

The primary focus of this work was to support the communities affected by the bushfires that occurred in the summer of 2019–20. It is apparent that there will be a long tail to the mental health impact of that event, not in the least exacerbated by the ongoing pandemic and other fire and flood events. For first responders, these extraordinary events add to the burden of an inherently high-stress occupation. Fortem will continue to extend the reach of its services that augment and complement existing supports.

The quantitative data from the wellbeing programs shows good engagement with protective factors and important mechanisms of wellbeing. The qualitative data gives a rich account of participants’ experiences and perceptions of outcomes and social connectedness emerged as a dominant theme. However, it is difficult to obtain meaningful quantitative data about sustained effects without longer-term follow up. Our aim is to partner with a first responder agency to pilot a longitudinal study exploring the lasting outcomes of wellbeing activities.

I have seen others that I have invited… begin to understand and reach out far more willingly because of the acceptance from others around them at events and the idea that these programs… are all directed at the lifestyle and career workings of [our] unique jobs.

(Survey participant response)

Lifestyle programs are often viewed as alternative to other mental health care. Mental fitness and resilience training programs often put the emphasis and onus on the individual, neglecting the important and powerful variable of social connectedness. We argue that facilitated wellbeing and social connection activities can not only be augmentative to traditional mental health interventions, but that social connection in and of itself can function as a primary lever of wellbeing and resilience in the first responder community.

Despite some limitations, the wellbeing program data indicates that facilitated social connection activities may not only strengthen social networks and enhance protective factors, but can also serve as a ‘soft entry’ into clinical services that allow first responders to benefit from evidence-based treatment for work-related psychological injuries. The clinical services outcomes suggest that, with early intervention (many participants indicated this was their first use of a psychological support service), compromised mental health and wellbeing can largely be restored. These outcomes may help reduce the burden of stress leave on first responder agencies and improve vocational functioning and career longevity for first responders. But more than this, we hope that this truly holistic approach leads to meaningful improvements in the quality of life of first responders and their families.

Endnotes

1. Lawrence D, Kyron M, Rikkers W, Bartlett J, Hafekost K, Goodsell B, Cunneen R 2018, Answering the call: National Survey of the Mental Health and Wellbeing of Police and Emergency Services. Detailed Report. Perth: Graduate School of Education, The University of Western Australia.

2. Royal Melbourne Hospital 5 Ways to Wellbeing, at https://5waystowellbeing.org.au/who-we-are/.

3. Barratt P, Stephens L & Palmer M 2018, When Helping Hurts: PTSD in First Responders. Australia p.21.

4. Jonas DE, Cusack K, Forneris CA, Wilkins TM, Sonis J, Middleton JC, Feltner C, Meredith D, Cavanaugh J, Brownley KA, Olmsted KR, Greenblatt A, Weil A & Gaynes BN 2013, Psychological and Pharmacological Treatments for Adults With Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD): Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 92. (Prepared by the RTI International-University of North Carolina Evidence-Based Practice Center Under Contract No. 290-2007-10056-I). AHRQ Publication No. 13-EHC011-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.