Australians are some of the lightest consumers of news in the world.1 Although the start of the pandemic saw a rapid increase in news consumption as people yearned for information, that has since dropped away.

In 2021, heavy news use dropped from 69% in April 2020 back to a level lower than pre-pandemic years (51% in January 2021).2 This is proof that, even with the threat of COVID-19 hanging over their heads, many people did not have the enthusiasm to consume news on a regular basis.3

Given our tendency to avoid news, it is not surprising that platforms such as Facebook, Twitter and Instagram have become an integral part of how many people communicate life-saving information in an emergency. In stark contrast to these news habits, people in Australia are among the heaviest social media users in the world. According to the Yellow Pages Social Media Report, almost 80% of the population use social media platforms. What’s more, they’re active from the morning with 58% admitting to checking social media as soon as they wake up.4

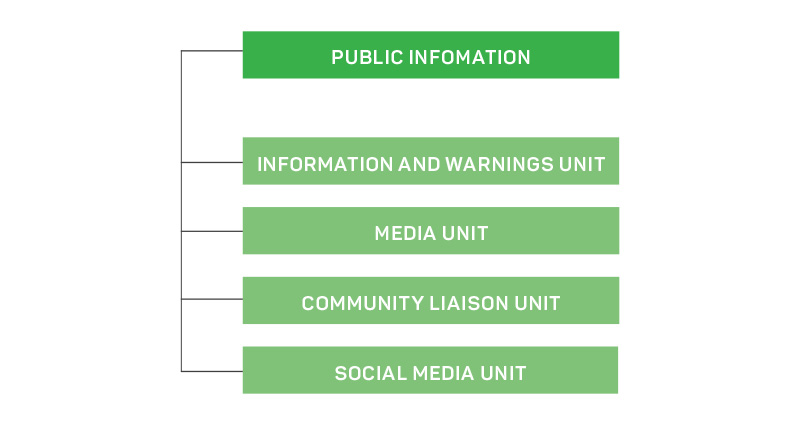

Social media and its usefulness in emergency management is acknowledged in the structure of the Public Information Section within the Australasian Inter-service Incident Management SystemTM (AIIMS). But just one, stand-alone Social Media Officer sitting in the Information and Warnings Unit is no longer enough. Even with a Social Media Support Officer added to the mix, the current system doesn’t reflect how much time, energy and resources it takes to properly manage social media during an emergency. It’s time to spin social media out into its own unit, allowing for the creation of roles to manage and moderate online content.

In a Level 3 incident, information and warnings, media and community liaison become too big for a Public Information Officer to handle alone. AIIMS has a built-in redundancy for this, allowing the Public Information Officer to appoint officers to manage each unit.5 Although it’s currently housed underneath the Information and Warnings Unit, social media isn’t solely an information and warnings tool. It’s not media or community liaison either. It’s a unique environment, feeding from and into all 3 Units in the Public Information Section.

Each unit in the Public Information Section of AIIMS reflects the need for specific knowledge and training that one needs to do the job. Social media is a multi-billion dollar industry that requires time and patience to master. It’s a skillset that is completely independent of the one needed to work within the Information and Warnings Unit.

It’s no secret that large emergencies are rarely managed by one agency. We help each other out; throwing people and resources at a disaster that might not be ours to manage. In such situations, it’s essential that we’re all speaking the same language, that we have a ‘consistent and universally understood and applied system’.6 This means that we can (and frequently do) take a Public Information Officer from one agency and have them manage communications in a completely different environment to one they are used to. AIIMS takes a large part of the guesswork out of what roles should be filled and when during an emergency. This allows for a consistent approach, better decision-making and less wasted time. It’s for this reason that social media needs to be its own unit. The less time we spend guessing what we need to do and when, the more people we can help.

Another reason why social media should be its own unit relates to maintaining a proper span of control, keeping the number of groups or individuals that can be successfully supervised by one person to a ratio between 1:3–1:7. Although it is not part of the formal definition7, span of control should also apply to the number of tasks or functions that one person can supervise. Adding more staff and resources to manage social media is one thing, however, it's only by creating its own unit that we can maintain a proper span of control in a large incident. As noted in AFAC (2017):

Organising the responders, so everyone understands what their task is, and who they are working with a reporting to, is central to the effective and safe management of an incident.8

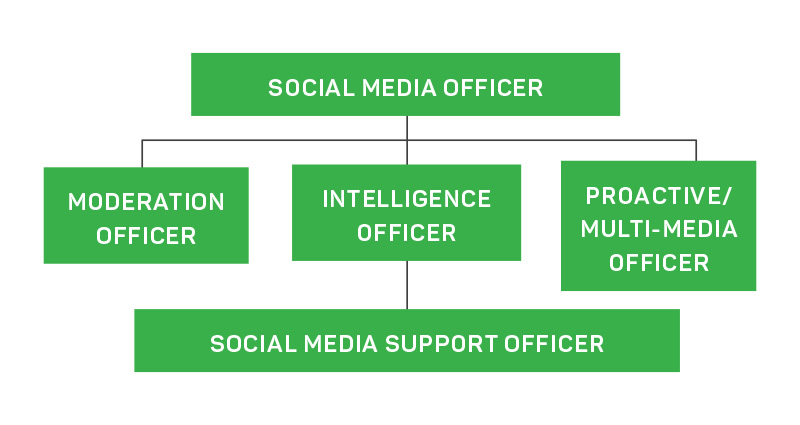

Much like the Media Unit, the basic structure of the Social Media Unit could include a Social Media Officer and Social Media Support Officer. In a Level 3 IMT, the Social Media Unit could be expanded to include roles such as a Moderation Officer, Social Media Intelligence Officer and Proactive/Multi-Media Officer. The tasks these roles would be responsible for are consistent and need to be filled in most major incidents.

Figure 1: What the structure of the Public Information Section would look like with a Social Media Unit

The most important role after a Social Media Officer is the Moderation Officer. The world of social and new media is filled with misinformation and, too often, a harmless-looking comment on a post turns into a rumour that can have the Media Unit trying to clarify a false story. But even if such a comment gains no traction and goes nowhere, it is still dangerous. Following the wrong information in an emergency can lead to injury and death; something we try very hard to prevent. It’s very easy for someone to read advice on a post and believe it because there is no one in the Public Information Unit given the sole task of responding to and moderating comments on social media.

The next most valuable role is a Social Media Intelligence Officer. Gathering information and passing it onto the Intelligence Unit is one of the essential functions of the Public Information Section9, yet it is normally one of the first to fall by the wayside in a crisis when the pressure is on and help is in short supply. Having a Social Media intelligence Officer dedicated to finding and passing on information would be invaluable in large-scale events.

Lastly, appointing a Proactive or Multi-Media Officer to help coordinate what should be published and when would help to keep the flood of content that needs to be published during an emergency to a manageable level. This role could also process or edit video content to help the Media Unit package footage for TV networks and YouTube channels.

Figure 2: What the structure of the Social Media Unit might look like in a Level 3 IMT.

Having a good social media presence can make all the difference in a crisis. The first place time-poor and overworked journalists go for updates is a Twitter or Facebook account. Videos posted to social media can gain hundreds or thousands of views within minutes, spreading necessary information far and wide. While radio is still king in areas where a disaster has brought down telecommunications infrastructure, social media helps emergency services organisations reach a larger audience. It can raise awareness and build resilience, making communities aware that they, too, might need to be prepared for a flood or fire one day. The importance of social media in Australia can’t be overstated, yet its place is not reflected in the current AIIMS structure. The first step towards taming the beast that is social media is to give it its own unit, allowing for a set structure of roles that all emergency services agencies can understand and use.

Endnotes

1. Fisher C, Fuller G, Park S, Young Lee J & Sang Y 2019, Australians are less interested in news and consume less of it compared to other countries, survey finds, The Conversation. At: https://theconversation.com/australians-are-less-interested-in-news-and-consume-less-of-it-compared-to-other-countries-survey-finds-118333.

2. Park S, Fisher C, McGuinness K, Lee JY & McCallum K 2021, Digital News Report: Australia 2021. Canberra: News and Media Research Centre, University of Canberra. At: https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2021-06/apo-nid312650_0.pdf.

3. Park S, McGuinness K, Fisher C, Lee JY, McCallum K & Nolan D 2022, Digital News Report: Australia 2022. Canberra: News and Media Research Centre, University of Canberra. At: www.canberra.edu.au/research/faculty-research-centres/nmrc/digital-news-report-australia-2022.

4. Teng K 2022, Surprising social media statistics about Australia, Yellow Pages. At: www.yellow.com.au/business-hub/surprising-social-media-facts-about-australia.

5. Australasian Fire and Emergency Service Authorities Council 2017, The Australasian Inter-service Incident Management System: A management system for any emergency 2017, AFAC Ltd, East Melbourne, VIC Australia, p.121.

6. Australasian Fire Authority Council 2004, The Australasian Inter-service Incident Management System: A Management System for any Emergency, 3rd edn. At: https://training.fema.gov/hiedu/docs/cem/comparative%20em%20-%20session%2021%20-%20handout%2021-1%20aiims%20manual.pdf.

7. Australasian Fire and Emergency Service Authorities Council (AFAC) 2017, The Australasian Inter-service Incident Management System: A management system for any emergency 2017, AFAC Ltd, East Melbourne, VIC Australia, p.15.

8. Australasian Fire and Emergency Service Authorities Council (AFAC) 2017, The Australasian Inter-service Incident Management System: A management system for any emergency 2017, AFAC Ltd, East Melbourne, VIC Australia, p.3.

9. Australasian Fire and Emergency Service Authorities Council (AFAC) 2017, The Australasian Inter-service Incident Management System: A management system for any emergency 2017, AFAC Ltd, East Melbourne, VIC, Australia, p.125.