Author

Author

Chas Keys

Reviewed by

Andrew Gissing, Natural Hazards Research Australia

Published by

Flood Plain Publishing

ISBN: 0646818759, 9780646818757

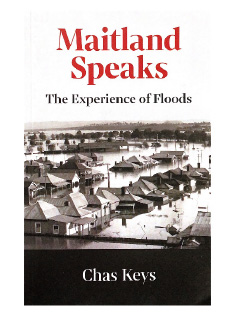

Our nation’s history is entwined with disasters. Many of us have experienced disaster first-hand. In my youth, growing up in the hills of the Murrumbidgee Valley, my grandparents would share their experiences of flooding. Instilling knowledge that would continue in its application for decades. It is the immense value of storytelling that Chas Keys captures in his accounts of those that have experienced flooding in his latest book Maitland Speaks: The Experience of Floods.

Keys, a former Deputy Director General of the NSW State Emergency Service, has been a keen observer of the Australian experience of flooding, with a particular interest in people living in the New South Wales Hunter Valley. The experiences of residents in the valley provides a rich tapestry to understand the effects of flooding and the challenges posed to communities in their adaptation to flood risk.

The book comprises 2 parts. Firstly, Keys explores the stories of 12 long-term Maitland residents stretching back as far as 1930 to illustrate the importance of understanding social perspectives that define the responses of individuals to flooding.

In each story, Keys captures the human emotion and experience as well as the practicalities of flood adaptation through a practitioner’s lens. The story of Lillian Adams is one of many interesting examples Keys explores. Following the devastation of the Hunter River flood in 1955, Lillian’s mother participated in a scheme arranged by the local Lions Club to relocate her home and many others to higher ground. The home is still occupied today after being dismantled and relocated.

The second part provides a synthesis of the community’s adaptation to flood hazard. As Keys describes, flooding has been ingrained in the local culture and the experiences of individuals has shaped the response to floods, although the absence of significant floods in recent decades has led to apathy. Brought about by construction of levees, apathy has disrupted the community’s connection with the flood threat as flooding has become less frequent. As Keys says:

Floods are not simply reacted to logically but produce understandings that are subjective and may in some cases be in error or otherwise not necessarily to people’s advantage: there is much community psychology to be uncovered in this.

Keys rightly challenges authorities not to be lured by a false sense of security created by flood mitigation but to maintain a close connection with the flood threat and its prudent management.

I particularly enjoyed the book’s collation and description of local flood-themed literature and arts that succinctly captures the community’s experience. A verse from the poem, ‘The Hunter and His Prey’, by Archer Crawford illustrates many of Keys’s arguments for the community to respect the inevitability of flooding.

Go bury your dead and weep for the bold

Who gifted the life that they’d sell not for gold.

Ask not for mercy, you damned Maitland men

Prepare for tomorrow, I’ll flood you again.

Overall, the book is an important contribution to disaster literature through exploration and illustration of historical adaptation in a local community setting. The lessons described are relevant to all flood-prone communities and are useful to inform responses to modern-day disaster management challenges. All disaster managers keen to ensure lessons of the past are not forgotten will enjoy this book.