People with disability rely on different levels and types of function-based support. Access to this support can be compromised during and after a disaster.

People with disability are disproportionately affected1 and experience higher rates of injury and death as well as face increased challenges during disaster response and recovery.2,3,4,5 The Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030 calls for ‘a more people-centred preventative approach to disaster risk’. Australia, as a signatory to the framework must find ways to assist people to prepare for emergency events triggered by natural hazards. This includes people with disability and their support networks.

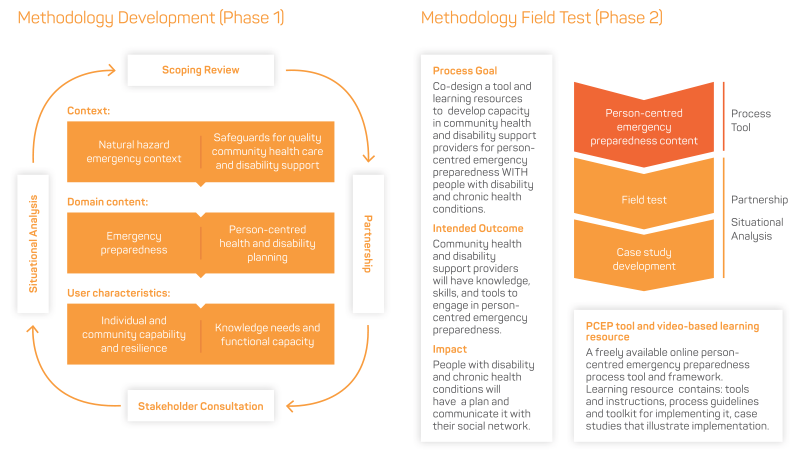

The Person-Centred Emergency Preparedness (PCEP) is a strengths-based process tool for people with disability and their service providers to develop emergency preparedness through self-assessment, targeted actions and advocacy relevant to the support needs they will have in an emergency. The PCEP was co-designed with 115 stakeholders from the disability, community and emergency services sectors. It was field-tested with people with disability in New South Wales and their community health and support providers. The project included a technical advisory committee that informed and guided the co-design process. Figure 1 illustrates the co-design methodology.

Figure 1: Co-design of the Person-Centred Emergency Preparedness Toolkit took place in two phases: Development and Field Test.

The PCEP enables people with disability to self-assess their emergency preparedness through the identification of capabilities and function-based support needs in eight areas: communication, management of health, assistive technology, personal support, assistance animals, transportation, living situation and social connectedness.

The PCEP classifies function-based needs that people with disability have in emergencies. Focusing on function enables more effective planning. For example, identifying risks for a person with spinal injury does not provide any information related to their support needs or how they will manage in an emergency situation. However, identifying disaster risk in terms of need for electricity to recharge batteries on a powered wheelchair and the importance of accessible transportation assists with effective problem-solving about how an individual will manage to shelter in place or evacuate safely.

The PCEP supports implementation of priorities outlined in the National Strategy for Disaster Resilience and the National Disaster Risk Reduction Framework by:

- defining person-centred responsibilities of people with disability to reduce their risks

- optimising the capability of service providers to contribute to disability-inclusive risk reduction through person-centred planning.

Person-centred preparedness conversations help people with disability to be involved in planning how they will respond in an emergency situation. Field tests showed that conversations about emergency preparedness can support people with disability to take steps towards increasing their preparedness. An open-access user guide and series of three videos illustrate how to implement the PCEP. The user guide contains quizzes and case examples to help people get started. As a person-centred planning tool, the PCEP supports community service staff to work with people with disability to:

- increase capacity for emergency preparedness

- reduce negative consequences of emergencies

- improve recovery.6

When an individual’s needs do not match the level of support available, community service providers are encouraged to work together with individuals, their family and other people in the community, including local emergency managers, to address those discrepancies through collaboration.

Eight elements of the PCEP framework

Communication: getting and giving information by speaking or using some other medium (sign language, picture exchange, voice output device). It includes the use of Augmentative and Alternative Communication (*AAC). It is also the means of sending or receiving information such as telephone or computers.

*AAC are communication methods used to supplement or replace speech or writing for those with impairments in the production or comprehension of spoken or written language.

Management of health: medical management of conditions include medicines, nutritional or health treatment, management of wounds, catheters or ostomies, access to medical supplies and equipment and their maintenance, operating power-dependent equipment to sustain life.

Assistive technology: any device, system or design that allows a task to be performed that can increase safety or make tasks easier.

Personal support: assistance received for personal care or support with activities of daily living. It can include practical and emotional support.

Assistance animals and pets: trained and registered animals that provide help people to participate in personal and public life activities with confidence and independence (e.g. mobility guide, hearing assistance, diabetic or seizure alert). A pet or companion animal also provides support but are not classified as assistance animals and pets.

Transportation: includes independent travel and travel with others (e.g. family, personal support, carers) and includes transport of assistive technology and assistance animals.

Living situation: covers where people live and the context of their home situation including who they live with, the type of building, how long they have lived there, its accessibility, safety, security and adequacy of the physical environment and the geographic location.

Social connectedness: are personal and professional relationships. Personal (family, friend, neighbour) and professional (service provider, community leader) relationships can vary in closeness (e.g. acquaintance vs. close friend) and can be with individuals who are similar in status or with individuals of varying status and power.

Adapted with permission from Villeneuve, Sterman and Llewellyn (2018).