The effects of climate change are particularly acute for children. Not only do these effects pose risks to children’s health, safety and survival in the near term, their younger age means they will be exposed to the increasing consequences into the future and for a greater proportion of their lives. As such, children are often presented in climate change debates, research and practice as being especially vulnerable and in particular need of support. However, this can lead to the portrayal of children as passive victims. This paper provides an overview of adaptation research and practice literature concerning children and young people, with a particular focus on whether and how child-centred responses to climate change can contribute to building the resilience of households and communities. In light of the increasing recognition of the roles of children and young people in climate advocacy, it is timely to consider how to more effectively include children in climate change adaptation action more broadly, and the consequences for them and their communities.

Introduction

It is well established that the impacts of climate change are already affecting the lives of children around the globe. The effects of climate change pose risks to children’s education, health, family security, safety and survival (Children in a Changing Climate 2005; Gibbons 2014; Goldhagen et al. 2020; Mitchell & Borchard 2014; Plan International 2015; Rahman, Ahsan & Rahim 2013; Reinvang 2013; UNICEF 2017a), and children are often disproportionately affected (Burgess 2011, Cabot Venton 2011, Chatterjee 2015, Mitchell 2016, UNICEF 2017b). Mirroring this acceptance from climate academics and practitioners, recognition is emerging from across a range of dedicated disciplines: for instance, a number of recent health and medical publications highlight the particular and disproportionate risks that climate change poses to children, including psychological affects as well as physical. Children and infants are, for example, disproportionately affected by dehydration and heat stress as well as by diarrhoeal diseases and, thus, are more vulnerable to increases in temperatures and changes in rainfall patterns (American Academy of Pediatrics’ Council on Environmental Health 2015; Goldhagen et al. 2020; Philipsborn & Chan 2018; Sheffield & Landrigan 2011; Stanberry, Thomson & James 2018; Xu et al. 2012). The direct and indirect consequences of climate change threaten children’s mental wellbeing, with fear and anxiety caused from concern about their futures even in the absence of direct impacts, as well as extreme stress and PTSD from exposure to specific climatic events (American Academy of Pediatrics’ Council on Environmental Health 2015; Burke, Sanson & Van Hoorn 2018; Goldhagen et al. 2020; Majeed & Lee 2017; Ojala 2016).

The equity concerns of climate change have also received increasing attention. The ‘Fridays for Future’ school strikes have helped to bring the issue of inter-generational justice to a mainstream audience (Warren 2019). Children have contributed least to the causes of climate change but will experience the effects long into the future. Climate change also impacts on different groups within society—and different kinds of children—differently, in ways that may exacerbate existing inequalities (Anderson 2010, Babugura 2016, Chatterjee 2015). For example, Johson and Boyland (2018) found that climatic changes and adaptation options are not uniform within a community, but varied depending on a multitude of factors. For instance, ethnicity, gender, marital status and age all affect whether migration in response to climatic changes is considered an available adaptation strategy within the communities they researched.

However, children are not passive victims; they can have agency, knowledge and capacity (Amponsem et al. 2019, Lawler & Patel 2012, Mitchell & Borchard 2014, Tanner 2010). Despite this, children’s particular vulnerability to climate change in the academic literature is rarely accompanied by a recognition of their potential contributions to action nor of possible benefits to themselves and to their communities from child-centred adaptation actions. Beyond the oft-cited (and somewhat patronising) idea that children can contribute to community adaptation activities through their enthusiasm and energy (Bartlett 2008, Cocco-Klein & Mauger 2018, Lawler & Patel 2012, Mitchell & Borchard 2014, Polack 2010), substantive examples and explanations are largely lacking.

This paper addresses this gap by bringing together practitioner-focused experiences with the emerging body of literature on child-centred adaptation research to demonstrate whether and how child-centred responses to climate change contribute to building the resilience of children, their households and their communities. This paper begins by summarising the existing literature, highlighting specific examples of child-centred adaptation actions from various practitioners, especially in the Global South1, that demonstrate concepts from the academic literature. Practice-based recommendations are then outlined.

The reviewed research shows that children can be effective communicators of climate risks and information, including information that leads to behaviour change. Children possess unique perceptions of risks. They have distinctive knowledge and experiences and are capable of identifying and implementing viable, locally appropriate adaptation responses. However, barriers remain that can prevent their inclusion and full participation in resilience-building programming.

Method

There is an emerging body of literature about child-centred adaptation, both from Australia and overseas. Search terms of academic literature included ‘climate change’, ‘adaptation’, ‘resilience’, ‘youth’ and ‘child’2. Grey literature was predominantly sourced from the websites of child-centred, practice-based organisations such as Save the Children, Plan International, World Vision and UNICEF, supplemented by publications from organisations with a climate change action or research focus (e.g. Oxfam or the International Institute for Environment and Development, IIED) where their publications included the relevant focus on both adaptation and children. The focus for this literature review was on articles published within the last decade, though some older publications have been included where they proved foundational.

Child-centred action on climate change: what works?

Relative to the substantial body of work on climate change, academic literature on child-centred adaptation is limited (Cocco-Klein & Mauger 2018, Mitchell & Borchard 2014). For example, a 2011 systematic literature review of English peer-reviewed academic literature on adaptation found that out of the 1741 articles that mentioned adaptation, only 87 were primarily about human-focused adaptation (as opposed to adaptation of natural systems, vulnerability, risk assessments, etc). Of those, only three papers explicitly mentioned children, the elderly or women (Berrang-Ford, Ford & Paterson 2011). While the corpus has grown somewhat since that systematic review, overall, the academic literature that focuses on child-centred adaptation remains scant. There is a larger, growing body of grey literature that documents practice-based interventions and the lessons learnt, predominantly focused on interventions in the Global South.

Some of the most effective and prevalent examples of improving children’s resilience include:

- climate change education to build skills and knowledge on climatic risks and possible adaptation strategies (Anderson 2010, Kabir et al. 2015) as well as education more broadly (Kwauk & Braga 2017)

- conducting child-centred climate vulnerability and capacity assessments to identify the specific risks and hazards climate change poses to a particular group of children (Children in a Changing Climate 2015, Plan International 2015, Rahman et al. 2013, Schoch & Treichel 2015)

- advocacy by children at local, national or international levels (Morrissey et al. 2015, Polack 2010, Swarup et al. 2011, Warren 2019).

The literature is also clear that participating and taking action on climate change provides children with confidence and self-assurance that can, in and of itself, be a form of resilience-building (Bartlett 2009; Boyden 2003; Sanson, Van Hoorn & Burke 2019; UNICEF Office of Research 2014). However, Brown and Dodman (2014) note that when activities of this kind are carried out as stand-alone, child-centred projects in isolation, the interventions tend to be short-lived and the outcomes not integrated into the community. Mitchell and Borchard (2014) express a similar concern. The long-term benefits of discrete child-centred adaptation activities that are not integrated into community programming are thus uncertain.

Well-designed and child-centred interventions have multiple benefits. For example, including children in both climate risk assessments and in adaptation design helps to avoid the risk of maladaptation (Lawler & Patel 2012, Tanner 2010). Children possess unique perceptions of the risks they face as well as distinctive knowledge and experiences (Babugura 2016, Bartlett 2008, Lawson et al. 2018, Reinvang 2013, Tanner 2010). When their intimate understanding of their own lives and vulnerabilities is combined with appropriate information gained from external information sources, they are capable of identifying both relevant climatic risks and viable, locally appropriate adaptation strategies (Bartlett 2009, Boyden 2003, Brown & Dodman 2014, Gibbons 2014, Lawler & Patel 2012, Mitchell & Borchard 2014). For example, Polack’s study on children in Cambodia and Vietnam found that:

Children are an integral part of household and community adaptation and are engaged citizens. Their identification of adaptation strategies is comparable to adults, and they often know clearly who is responsible for delivery. Evidence gathered from the children participating in this research demonstrated their aptitude for: absorbing new information; proposing adaptation strategies; acting on their future visions and the needs of future generations; taking action for the benefit of their community; and prioritising sustainable management of natural resources.

(Polack 2010, p.36).

Similarly, Tanner’s research on child-led responses to climate change in El Salvador and the Philippines demonstrated that children:

…have a close awareness of the risks facing their lives, identifying the complex mix of hazards as well as the people, families or geographical areas where greater vulnerability to these hazards exists.

(Tanner 2010, p.343).

In research from Bangladesh, children were able to identify multiple appropriate adaptation actions they could take (Chatterjee 2015). Similarly, a 2015 Plan International report outlined that children in Fiji identified coastal erosion resulting from rising sea-levels as an issue for their community. The children determined that mangrove planting would be an appropriate response and, through a child-centred project, the children purchased, planted and maintained the mangroves to effectively recover the beachfront (Plan International 2015). In Zambia, a UNICEF child-led advocacy program has empowered approximately 1000 teenagers aged 11–17 years to become climate ambassadors who engage in peer-to-peer outreach and activities. The project claims many impressive results, including the planting of 30,000 tress, the construction of a floating school in an area susceptible to flooding and the uptake of conservation agriculture by small-holder farmers (UNICEF 2015). In Ghana, young people have worked with the National Disaster Management Organisation to conduct risk assessments and update early warning risk maps. They have also undertaken work that supports the community by clearing drainage systems and building makeshift levees of sandbags (Amponsem et al. 2019). Integrating child-centred adaptation activities and interventions into the plans, policies and programs for the community can thus have benefits not only for the children involved, but also for their families and society broadly.

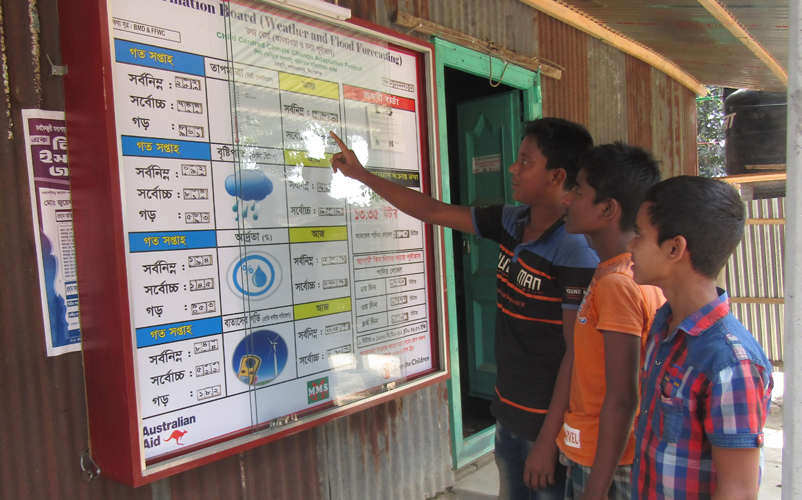

Sirajganj district in Bangladesh is prone to floods and other climatic hazards. Through technical sessions, children learnt about climate change and adaptation actions and were able to understand weather and flood information and forecasts and respond appropriately. Image: Mohammad Badrul Alam Talukder, Save the Children

Effective communicators: for households, communities and beyond

The literature reveals a body of evidence showing that taking a child-centred approach to adaptation can benefit children, their households and the community (Bartlett 2009; Cocco-Klein & Mauger 2018; Lawler & Patel 2012; Mitchell & Borchard 2014; Rahman, Ahsan & Rahim 2013; Tanner 2010). Child-centred activities can be an entry-point for other community activities (Mitchell & Borchard 2014). At a pragmatic level, education resources and activities developed for children can also be used by adults, particularly in contexts where understanding of climate science is low (Cocco-Klein & Mauger 2018). For example, in Bangladesh, a project implemented by Save the Children identified multiple benefits to children and the community from undertaking child-facilitated, awareness-raising activities. Project activities included children leading discussions with other children at school, children facilitating discussions with adults (both men and women) in their community, children writing and performing plays and debates about climate change and children implementing demonstration actions such as creating climate-resilient gardens. According to Rahman, Ahsan and Rahim (2013) these events not only built children’s knowledge and skills, but also improved the understanding of members of the community of the causes, consequences and possible responses to climate change. Because information from children often permeates back through their families (Lawson et al. 2018; Mitchell, Tanner & Haynes 2009), this can also allow knowledge of climate risks to reach those who may not be exposed to other interventions (Schoch & Treichel 2015).

Children have also repeatedly shown themselves to be effective communicators of climate risks and information, including in ways that lead to behaviour change (i.e. adaptation) (Chatterjee 2015; Children in a Changing Climate 2015; Lawler et al. 2011; Turnbull, Sterrett & Hilleboe 2013). These changes might be in the behaviour of children (e.g. through peer education programs (Lawler & Patel 2012, Polack 2010)), or of their families and the community (Schoch & Treichel 2015). For example, in the Philippines, a child-centred adaptation program aimed to build children’s knowledge and confidence on climate change, including through developing a community radio show hosted by children, called ‘Bulilit Brodkasters’ (child broadcasters). During these shows, children facilitated discussions about the science and effects of climate change, disaster preparedness and climate change adaptation efforts in communities and schools. Climate change and disaster experts were invited onto the show to be interviewed by the children and answer phone or text questions from listeners. The project implementers noted that ‘research has found that such interactive programming creates a platform for two-way exchanges and learning, boosting the uptake of information’ (Schoch & Treichel 2015, p.28).

Another example is an energy and water-saving campaign from rural Vietnam. Children were taught simple resource-saving techniques that could be applied at home, such as switching off electrical appliances or ensuring water taps were fully closed. This allowed children to advocate to their parents about environmental issues and also provided their families with potential ways to save money. The children analysed their household bills to monitor progress. In the first three months of the project, the participating communities saved over 8.4 million VND (USD$388). The children’s efforts provided a financial saving for families with co-benefits for the climate (Schoch & Treichel 2015).

These practice-based examples are supported by developments in academic literature. For example, a recent paper in Global Environmental Change explored child-based communication for climate change action and noted that children’s ability to influence their parents’ behaviours has been well documented in other environmental fields. The authors go so far as to say that (at least in the United States):

...children appear to be the ideal conduit for climate change communication to their parents, as they are capable of understanding and acting on the subject more effectively than parents and are more trusted by parents than other information sources.

(Lawson et al. 2018, p.205).

As well as being effectual activists for climate action in their households, children can be successful advocates within and beyond their communities (Gibbons 2014, Lawler & Patel 2012). A clear and topical example is the school strikes led by Greta Thunberg that began in 2018. By early 2019, these had gained international attention and support. For example, on 15 March 2019, an estimated 1.4 million students in 112 countries joined in a strike and protest and more than 12,000 scientists signed a letter in support of the students’ demands (Cohen & Heberle 2019, Warren 2019). While Greta Thunberg is well-recognised internationally, there are many other youth activists globally, including Leah Namugerwa from Uganda (Sarwar 2020, The Green Market Oracle n.d.) and Brianna Fruean from Samoa (The Pacific Community n.d.).

An example from Papua New Guinea illustrates that children can be effective when adults are not. Plan International documented a local children’s group’s success in securing government assistance for their community after several unsuccessful funding applications by community leaders. The children’s group produced a short video and poster in which they outlined how climate change is impacting on their lives and their community. They were able to show these to a Member of Parliament who ‘immediately approved a start-up fund required to begin a project to build a sea wall’ (Plan International 2015, p.10).

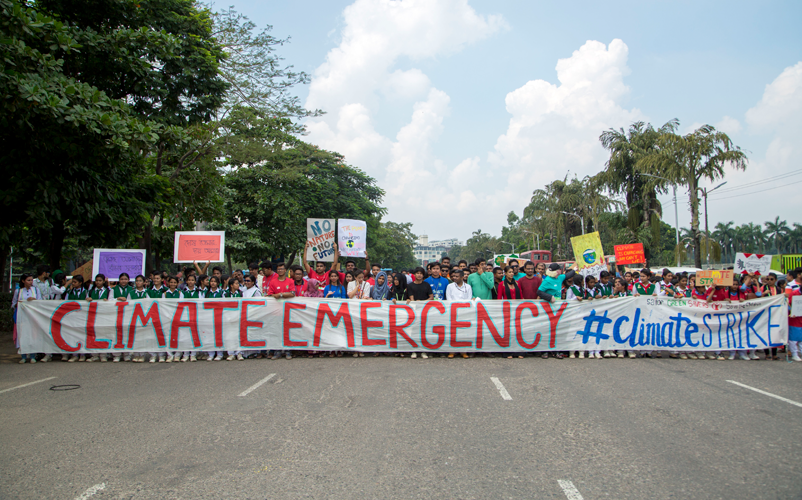

In September 2019, children from around the world participated in global strikes and marches, calling for action on climate change. In Bangladesh, more than 3000 children and their supporters gathered in front of Parliament in Dhaka urging world leaders to act. Image: Emdadul Islam Bitu, Save the Children

A rationale for inclusion

The economic benefits for communities as a result of child-centred initiatives are also highlighted in the literature as a rationale for undertaking more child-centred adaptation actions. For example, because many of the impacts of climate change will be felt in the future, investing in children’s resilience now helps to ensure the resilience of the community in the medium- to long-term (Cabot Venton 2011; Children in a Changing Climate 2015; Gibbons 2014; Schoch & Treichel 2015; Turnbull, Sterrett & Hilleboe 2013). The high vulnerability of children to the effects of climate change means that measures to reduce those vulnerabilities are also offsetting potential future costs to the community, particularly in terms of health and protection, and so are underscored as a wise economic investment (Cabot Venton 2011). Children are often one of the largest groups within a developing country’s population. Targeting their specific needs means the effects of climate change across a significant proportion of the vulnerable population can be reduced, thereby improving the efficacy of resilience projects (Children in a Changing Climate 2015).

Despite evidence of children’s competency identifying and implementing appropriate adaptation actions, there are significant barriers to achieve the full benefits of child-centred adaptation. Notwithstanding the above findings that children can be effective communicators of climate risk, children’s voices are often not heard at community or the household level, nor are their views taken into account in climate change decision-making (Babugura 2016, Tanner & Seballos 2012). At the government and policy level, children are often only considered in terms of their vulnerabilities, if they are included at all (Amponsem et al. 2019, Berse 2017, Mitchell 2016, Polack 2010). A recent publication from the Brookings Institute found that only 67 out of 160 countries’ Nationally Determined Contributions (a country’s formal submission to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC)) explicitly mentioned children or youth (Kwauk et al. 2019). Similarly, Thew and colleagues (2020) noted many challenges to meaningful youth participation in the UNFCCC, including difficulties gaining adequate recognition of young people’s role in the negotiations and a perceived ‘lack of formalized opportunities for them to provide input’ into the negotiations. Even within the increasingly large number of adaptation and resilience-building projects being implemented globally, children’s active participation remains limited (Berse 2017, Mitchell & Borchard 2014). Importantly, Mitchell, Tanner and Haynes (2009) noted that children may have valid concerns or motivations that limit their participation and that need to be overcome.

Recommendations

Much of the child-centred adaptation literature includes recommendations for effective child-centred adaptation actions, including as outputs from evaluations of implemented interventions. A summary of the primary recommendations is provided, many of which have direct practical applications for future program design and execution.

- Child-centred adaptation projects need to integrate activities for children and their communities from the outset (i.e. the design phase): Children's capacity to be effective change agents (for themselves and for their community) is limited if activities do not target their families as well as the children themselves (Plush 2008, Tanner 2010). Child-centred adaptation approaches should be equally about increasing the participation of children and engagement with households, communities, local and national governments and international organisations to ensure the effects last (Mitchell & Borchard 2014, Save the Children 2015). Moreover, while it is imperative that children be engaged in adaptation planning and decisions that affect them, it is also important that responsibility for solving the climate crisis is not left to children. This underscores the need for community-wide involvement.

- To ensure efficacy of activities, engage with existing structures and institutions (where these exist) (Chatterjee 2015): Several articles show that children can be effective agents of change when they have the adequate support and formal structures to do so. Tokenistic participation does not lead to enduring change (Brown & Dodman 2014, Tanner 2010).

- The active participation of targeted beneficiary groups is essential for long-term impact: In order for solutions to be appropriate for the context and to engender a sense of ownership from beneficiaries, adaptation actions need to be produced through participatory processes (Schoch & Treichel 2015). Predetermined, stand-alone or externally imposed solutions are unlikely to have lasting effect (Brown & Dodman 2014). Moreover, children and their local communities often know their own climate and climatic changes well (Tanner 2010), so including children and their communities in the design of adaptation actions allows responses to be developed that focus on the underlying drivers of vulnerability.

- Ensure adaptation activities target all children, including girls, boys, children with disabilities, ethnic minorities and others who may be overlooked (Johnson & Boyland 2018): Programs need to go beyond the assumption that certain groups—like children—are more vulnerable and begin to target the underlying barriers and constraints that make these groups more vulnerable in the first place.

- Understanding vulnerabilities (political, cultural, socio-economic, as well as climatic) is as important as technological innovations: Instead of focusing on externally provided ‘technological’ tools, resources should be focused on identifying and reducing underlying causes of vulnerability (Polack 2010). As Tanner (2010) noted, ‘no single model of child participation is universally appropriate for tackling … climate change’ (p.346). There are also multiple examples of the differences between rural and urban children’s contexts, noting that interventions that might have been appropriate in one of these geographies are inappropriate in the other (Brown & Dodman 2014, Chatterjee 2015, Lawler & Patel 2012).

Conclusions

There is an emerging body of evidence that indicates well-planned projects that integrate child-centred initiatives into the community in which they live can and do build the resilience of households and communities as well as the children themselves. Relative to other aspects of climate change, however, adaptation actions for children remain significantly under-researched.

The continued documentation and dissemination of examples of child-centred adaptation initiatives, both their successes and the lessons learnt, will be incredibly valuable, particularly within the academic literature. Areas for future research that would support these kinds of interventions include the characteristics of children’s vulnerability, their adaptive capacity and the resilience of communities (Lawler & Patel 2012, Sanson et al. 2019). In particular, examples that expressly showcase how different responses have been developed to respond to different kinds of child vulnerability would help to bolster knowledge in this area. Additional research to explain the critical features of successful child-centred adaptation programs, including the enabling environments that allows them to be replicated and sustained over time, would also be of great value (Mitchell & Borchard 2014).

Given that the effects of climate change are increasingly being felt, and the growing recognition of children and young people’s capacity to be effective advocates on the issue of climate change, it is time to increase children’s active participation in their own adaptation.