Australia’s summer bushfires of 2019–20 were a reminder that animals are increasingly exposed to risks from changing climate conditions. In Australia, differing organisational approaches to managing owned animals in disasters can lead to different welfare and safety outcomes for animals and the people responsible for them. The need for consistency was reinforced by recent Australian royal commission findings. In 2014, the Australia-New Zealand Emergency Management Committee endorsed the National Planning Principles for Animals in Disasters, a tool supporting best practice in emergency planning and policy for animal welfare. This study examines current planning for animals in disasters in relation to the principles and describes their implementation in the Australian context. A national survey of organisation representatives with a stake in animal management in disasters (n=137) and addressing the national principles implementation was conducted from July to October 2020. Findings show moderate awareness of the principles by respondents and low to moderate implementation of these in planning processes and arrangements for animal welfare. Implementation of specific principles is described from the perspectives of stakeholders. Greater awareness of the national principles and attention to specific principles promotes consistency in animal welfare planning arrangements.

Introduction

The summer bushfires in Australia in 2019–20 (Davey & Sarre 2020) and unprecedented loss of animal life reiterated the need for disaster planning, preparation and response that effectively includes animals. This is reflected in recommendations from Australia’s Royal Commission into National Natural Disaster Arrangements (Commonwealth of Australia 2020), where animal management and evacuation planning needs were highlighted and animals were indirectly implicated across various other recommendations (e.g. jurisdictional cooperation). In this particular natural disaster example, there was significant loss of animal life, with an estimated 3 billion animals killed or displaced (van Eeden et al. 2020), 1.8 million hectares across southeast Australia affected by bushfires (Bradstock et al. 2021) and 33 human lives lost.

In 2014, the National Planning Principles for Animals in Disasters (NPPAD) was released by the National Advisory Committee for Animals in Emergencies (2014) and endorsed by the Australia-New Zealand Emergency Management Committee (World Animal Protection 2015). The principles were designed as a non-prescriptive tool and aimed to promote best practice for integrating animals into disaster planning. The NPPAD comprises 24 principles; 8 relate to the planning process (Table 1) and 16 to disaster plans (Table 2).

The principles are referred to in this text by number, for example (P2), (P18). Following its endorsement, the principles were, to varying extents, incorporated into policies and plans at state and territory governments as well as at the local government level. However, since the Australian Government disbanded the National Australian Animal Welfare Advisory Committee in 2013, there has been no published information tracking the adoption of the principles nor assessing the utility of this guidance across disaster arrangements.

As Australia’s Disaster Risk Reduction Framework (Commonwealth of Australia 2019a) is largely silent on animals, further research and policy action is needed to promote effective integration of animals into Australia’s disaster response arrangements. Animal welfare in disasters has been framed as a risk issue for human safety (Trigg et al. 2017, Squance et al. 2018), a social value concern for animal displacement, injury or death (Rogers et al. 2019) and an economic consideration for industry (Campbell & Knowles 2011). As these issues span national research priorities for emergency management (Commonwealth of Australia 2019b), examining how the NPPAD is implemented in Australia will inform the policy agenda to benefit people and animals. Ideally, this can leverage the growing attention this receives in public discourse (Reed, DeYoung & Farmer 2020) and emergency response development (McKenna 2020).

This study examined awareness and implementation of the NPPAD in disaster planning arrangements in Australia to describe how these had been applied and to discuss future needs. This study is part of a larger project examining animal planning and policy principles in Australia.

Sheep penned within a burnt area after bushfire require water and food.

Image: NSW Department of Primary Industries, Local Land Services

Method

Design

A national survey was developed to examine awareness and implementation of the NPPAD by organisations with a stake in animal emergency management or welfare in natural disaster contexts. This study focused on owned animals (e.g. farmed animals, companion animals) although did not exclude stakeholders with responsibility for non-owned animals (e.g. wildlife). The 48 survey items took approximately 40 minutes to complete via a combination of multiple choice, rating scale and open-ended items. The questions addressed organisational perspectives on planning, policy and response for animal management in emergency and disaster events. These included organisation characteristics, awareness of jurisdictional emergency arrangements for animals, awareness of the NPPAD and how these were implemented to support animal welfare. Implementation questions focused on how the principles were applied in the process of creating and maintaining plans for animals (i.e. planning process) and how the principles were represented in the final emergency planning arrangements (i.e. disaster plan). Scoping conversations with stakeholder representatives and a literature review informed the survey design. Questions relating to specific principles also required open comments about implementation.

Procedure

The confidential survey was administered using Qualtrics (Provo, UT) via a shareable link emailed to stakeholder groups and identified organisation representatives. The email included a study description and a participation and consent summary. Contacts were identified from hearings of the 2020 Royal Commission into Natural Disaster Arrangements, state emergency response organisations and government departments, as well as social media and email networks of professional associations. Participants were aged over 18 years and were currently or formerly employed in a role involved in planning, policy development and response for animals in emergencies and disasters. This included government agencies (e.g. agricultural departments, emergency services organisations), local government, animal organisations and not-for-profit organisations. Data were collected between July and October 2020 and a reminder email was sent prior to the survey’s close. Statistical analyses are largely descriptive and tested categorical differences where appropriate (e.g. Fisher’s test).

The study was approved by the Macquarie University Human Research Ethics Committee (Reference number: 6757).

Participants

Of the 215 eligible organisations and individuals consenting to the survey, 137 provided responses. As the survey was directed to animal management stakeholders, this represents a high degree of engagement with the target audience. Participant organisations were primarily from New South Wales (26 per cent), South Australia (15 per cent), Western Australia (15 per cent), Queensland (11 per cent) and Victoria (11 per cent), with 10 per cent reporting national jurisdiction, ‘Other’ (6 per cent), Tasmania (4 per cent) and Northern Territory (0.7 per cent). ‘Other’ included those who had held roles in Australia and New Zealand. Participants worked in state and territory government bodies (26 per cent), local government (21 per cent), emergency services organisations (13 per cent), not-for-profit organisations (26 per cent), professional associations (3 per cent), private companies (3 per cent) and other organisations (8 per cent).

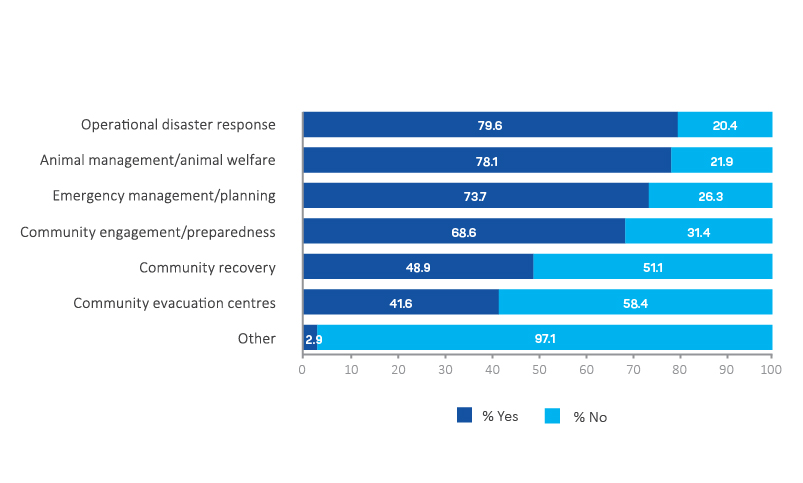

Participant roles at their organisations were primarily described as emergency management (35 per cent), animal welfare management (27 per cent), veterinary response (13 per cent) and industry representation (7 per cent). Figure 1 shows participant areas of oversight for disasters and emergencies were largely in operational response, animal management and welfare, emergency management and planning, and community engagement and preparedness. Participants could select multiple oversight areas.

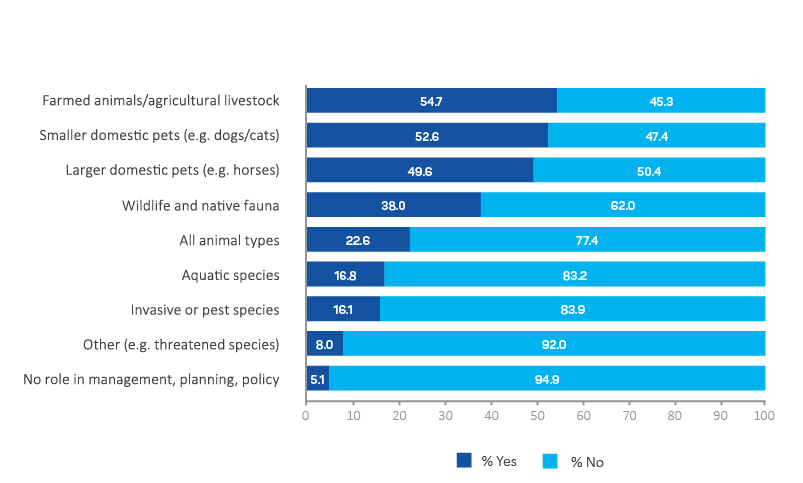

Most participants described their current role (89 per cent) and had direct contact with animal owners in this role (75 per cent). Across organisation types, direct contact with animal owners was most often reported by respondents from state and territory governments (69 per cent), local government (97 per cent), emergency services organisations (83 per cent) and not-for-profit organisations (85 per cent), compared to those from professional associations (67 per cent), private companies (67 per cent) or other organisations (56 per cent). Figure 2 shows that respondents from stakeholder organisations most often held responsibilities for farmed animals and agricultural livestock, domestic pets, wildlife and all animal types. In this context, ‘all animals’ refers to the ‘all species’ perspective taken by some organisations in disaster response and management.

Most respondents felt that their organisation should have responsibility for animals in emergency or disaster situations (55 per cent). While 25 per cent of respondents felt they should have more responsibility, 17 per cent desired no responsibility for animals.

Results from the survey sample are presented as a whole. Given the sample profile, these data should be viewed as broadly representative of Australian organisations with a stake in animal emergency management.

Figure 1: Stakeholder role areas of oversight for disasters and emergencies (n=137).

Figure 2: Stakeholder organisation responsibility for animal types in disasters and emergencies (n=137).

Results

Awareness of the NPPAD

Comments were provided describing levels of awareness and implementation of the principles (n=105). More than half of the respondents were aware of the NPPAD (58 per cent) with approximately a third (31 per cent) unaware of them and some were unsure whether they had encountered them (11 per cent). This suggests increased active promotion of the principles to organisations with a stake in animal welfare and management (e.g. through targeted information campaigns) is required.

Open responses for describing understanding of how the NPPAD is used in Australia suggest that respondents regarded the principles as a useful guide for planning rather than providing operational information. Example responses include:

The safety and welfare of people remains the overarching priority at all times—this is the key principle reflected in our planning. We are currently using [the] principles in our review of our local emergency animal welfare plan.

(local government)

They are a set of guidelines organisations can use and base their policy, practices, and procedures on.

(state/territory government)

The principles were used as a framework, and [were] considered in the development of the City’s Animal Welfare Plan.

(local government)

They are directly applied in this state as a result of our lead animal agency.

(state/territory government)

The principles inform our policy development work, although they are due for an update to bring them into line with contemporary emergency management practice and language.

(private company)

We are mindful of the principles, but the document has no operational information.

(state/territory government)

I know they exist, and have looked at them, but operationally, we remain focused on what our organisation requires and what works on the ground.

(state/territory government)

Descriptive analysis also suggests that, for respondents who were ‘unaware’ of or ‘unsure’ if they had encountered the principles (n=44):

- Over half felt that the official responses for animals could be improved (59 per cent).

- Over half held responsibilities for community engagement on disaster preparedness (57 per cent).

- Many held responsibilities for operational disaster response (73 per cent).

- Many held responsibilities for animal management or animal welfare (71 per cent).

- A third held responsibilities for community evacuation centres (30 per cent).

- Over half held responsibilities for emergency management planning (59 per cent).

- A third held responsibilities for community recovery (34 per cent).

These figures and comments indicate there is some level of awareness of the intended use of the NPPAD in informing animal emergency planning, however, an increased awareness of the principles is needed given respondent role responsibilities.

Implementation of the NPPAD

In general, of the respondents who were aware of the NPPAD (58 per cent), just over half (54 per cent) had implemented them to some degree in animal emergency planning and policy arrangements of their organisation. Respondents were asked for each NPPAD principle individually, whether they had fully, partially or had not implemented the principle or if it was not applicable to them. To provide a simple overview of implementation of the NPPAD, ‘overall’ data are the focus in this study (i.e. the sum of respondents who had either ‘fully’ or ‘partially’ implemented the areas covered in each principle), but all response categories are provided. The results are presented in Table 1 relating to the ‘planning process’ and Table 2 relating to the principles and ‘disaster plan’ arrangements.

Implementation in the planning process

Almost three-quarters of respondents (73–74 per cent) reported integrating needs of animals into their disaster planning to improve human and animal welfare outcomes (P1, P2) and that their planning processes clearly identified roles with animal welfare responsibilities (P3). However, just under two-thirds of stakeholders (62–63 per cent) reported that they recognised and consulted with a wide range of parties when writing and reviewing plans (P4) or included effective communication about plan implementation with those likely to be involved or affected (P7).

Fewer again (58 per cent) reported that their planning process respected the role of local government or local government expertise in understanding local needs (P5) or considered effective integration of animal welfare in planning processes and training (P6). This suggests that despite acknowledgment of the importance of integrating animals into disaster planning processes, there is still a need to be better involved with relevant audiences. In particular, the accessibility of language used in the planning process for stakeholders including the general public (P8) was the area least likely to have been fully implemented. This suggests that the planning process was more likely to include technical or expert audiences or would be less understandable by general audiences.

Table 1: Stakeholder organisation endorsement of the National Planning Principles for Animals in Disasters in Planning Processes (n=90).

| Implementation | |||||

| Fully | Partially | Overall | Not | N/A | |

| The planning process should: | |||||

| P1. Explicitly recognise that integrating animals into emergency management plans will improve animal welfare outcomes. | 47 (52%) |

19 (21%) |

66 (73%) |

6 (7%) |

18 (20%) |

| P2. Explicitly recognise that integration of animals into emergency management plans will help secure improved human welfare and safety during disasters. | 46 (51%) |

21 (23%) |

67 (74%) |

6 (7%) |

17 (19%) |

| P3. Aim, for the benefit of emergency managers and animal welfare managers, to clearly identify roles and responsibilities within command-and-control structures in sufficient detail to allow for effective implementation of animal welfare measures. | 41 (46%) |

23 (26%) |

64 (71%) |

6 (7%) |

20 (22%) |

| P4. Recognise the wide range of parties involved in animal welfare at each stage of the disaster cycle and ensure these organisations are consulted during writing or reviewing disaster plans. | 32 (36%) |

24 (27%) |

56 (62%) |

14 (16%) |

20 (22%) |

| P5. Respect the role of local government, especially with reference to animal welfare and animal management arrangements within the local area, as ‘first responders’ in disasters and acknowledge local government expertise in understanding local needs and resource availability. | 31 (34%) |

21 (23%) |

52 (58%) |

17 (19%) |

21 (23%) |

| P6. Consider how best to ensure effective integration and implementation of the plan by, for example, extensive consultation during the planning process or inclusion of an animal welfare element in requirements for disaster training exercises. | 28 (31%) |

24 (27%) |

49 (58%) |

13 (14%) |

25 (28%) |

| P7. Include effective communication about plan implementation with those parties who may be involved as well as those who may be impacted by disasters. | 28 (31%) |

29 (32%) |

57 (63%) |

10 (11%) |

23 (26%) |

| P8. Be communicated in language that is accessible to all stakeholders including the general public. | 23 (26%) |

29 (32%) |

52 (58%) |

13 (14%) |

25 (28%) |

Note: Frequencies and valid percentages reported. N/A responses were self-selected. Percentages have been rounded.

Implementation in disaster plans

Reviewing the implementation of the NPPAD in emergency and disaster plans, a greater proportion of respondents (71 per cent) indicated that their plans specified that the person in charge of an animal held ultimate responsibility for the animal’s welfare (P9) and the same proportion included an outline of processes for inter-agency cooperation disaster stages (P21). There were also relatively higher levels (62 per cent) of consideration for scaling up response and resources to match the effects of disasters on human and animal welfare (P17) and in using accessible language to describe command-and-control structures (P20). Respondents indicated greater inclusion of systems for formalising animal welfare support arrangements (P22), consideration of logistical challenges (P23) and having situated their plans within jurisdictional regulatory and legal frameworks (P10). All these requirements are fundamental for effectively executing plans and suggest that practical and operational issues were relatively well considered in disaster planning. Additionally, a similar proportion of respondents had adopted an all-hazards and all-species approach to animal welfare (P11), although it should be noted that some organisations have a specific disaster or species focus.

Around half of the respondents indicated their organisation’s plan focused on disaster types most likely to affect animals in their jurisdiction (P13) and just under half of respondents indicated their planning arrangements considered animals at all stages of the cycle (i.e. preparedness, response, recovery and mitigation) (P14). For those not developing plans across all stages, a greater focus was placed on animal welfare in the preparation (71 per cent) and response (87 per cent) stages, relative to recovery (63 per cent) and prevention (46 per cent), suggesting that further emphasis on animal welfare planning in risk reduction and in post-disaster stages would be beneficial. Around this mid-level of implementation was the inclusion of requirements and arrangements for regular testing and review of plans (P24). Although periodic review and testing forms part of planning processes, it is evident that these aspects are not always undertaken where animal welfare is a focus.

Four principles with relatively lower levels of implementation (36–42 per cent) were noted. Relatively few respondents reported the inclusion of vision statements in plans that outlined the value of securing animal welfare (P18) or included rationale statements describing the broad benefits to animal welfare, human wellbeing and the economy of integrating animals into disaster planning (P19). This is interesting, given the greater recognition of the importance of animal integration to human and animal safety in planning processes. The principles least likely to be implemented were including an emphasis that biosecurity is important and biosecurity protocols must be followed as far as possible (P16) and explicit mention that animal disease and biosecurity emergencies are out of scope in the disaster plan (P15). An initial explanation for this overall lower level of implementation is that around a third of stakeholders reported that P16 was ‘not applicable’. This finding may reflect the organisational profile of the sample in the study.

Table 2: Stakeholder organisation endorsement of the National Planning Principles for Animals in Disasters in Disaster Plans (n=83).

| Implementation | |||||

| Fully | Partially | Overall | Not | N/A | |

| The disaster plan that incorporates animals should: | |||||

| P9. Specify that the individual in charge of an animal is ultimately responsible for its welfare in disasters. | 35 (46%) |

19 (25%) |

54 (71%) |

4 (5%) |

18 (24%) |

| P10. Make reference to, and situate the plan within, the local area and/or jurisdictional regulatory and legal frameworks. | 29 (35%) |

18 (22%) |

47 (57%) |

14 (17%) |

22 (27%) |

| P11. Take an ‘all hazards’ humane approach to all species and encompass a wide range of possible disaster-type situations that may impact upon the welfare of livestock, companion animals, wildlife and other categories of animals such as laboratory animals. | 18 (22%) |

29 (35%) |

47 (57%) |

18 (22%) |

18 (22%) |

| P12. Use a definition of disaster that aligns with the National Strategy for Disaster Resilience | - | - | - | - | - |

| P13. Appropriately plan for animals taking into consideration the types of disasters most likely to be experienced in the particular jurisdiction. | 25 (32%) |

15 (19%) |

40 (51%) |

16 (21%) |

22 (28%) |

| P14. Include consideration of animals at all stages of the disaster cycle including preparedness, response, recovery and mitigation. | 27 (47%) |

- | 27 (47%) |

30 (53%) |

- |

| P15. Include a statement of scope that excludes animal disease and biosecurity emergencies from the plan. | 18 (23%) |

10 (13%) |

28 (36%) |

28 (36%) |

22 (28%) |

| P16. Emphasise that biosecurity requirements are of utmost importance in disasters and that quarantine and biosecurity protocols must be followed wherever practicable. | 18 (23%) |

15 (19%) |

33 (42%) |

19 (24%) |

26 (33%) |

| P17. Provide for a staggered scaling up of response and resources in line with the scale and severity of disasters and their impact on animal and human welfare. | 24 (31%) |

24 (31%) |

48 (62%) |

13 (17%) |

17 (22%) |

| P18. Include a vision statement that makes reference to the importance of securing animal welfare outcomes in disasters. | 17 (21%) |

16 (19%) |

33 (40%) |

31 (37%) |

19 (23%) |

| P19. Include a brief rationale statement that includes reference to the benefits of the plan for animal welfare, human safety and wellbeing and for the economy. | 9 (11%) |

25 (30%) |

34 (41%) |

26 (31%) |

23 (28%) |

| P20. Outline command-and-control structures in language that is accessible to the general public. | 23 (30%) |

25 (32%) |

48 (62%) |

10 (13%) |

20 (26%) |

| P21. Outline the processes for interagency cooperation at all stages of the disaster cycle. | 35 (46%) |

19 (25%) |

54 (71%) |

4 (5%) |

18 (24%) |

| P22. Include a system for formalising arrangements with animal welfare support organisations. | 22 (29%) |

22 (29%) |

44 (58%) |

12 (16%) |

20 (26%) |

| P23. Take into consideration logistical challenges that may impact upon implementation of the plan during disasters, for example, in the event that key infrastructure or personnel are not able to be deployed, communication is affected or shelters are destroyed or otherwise unavailable. | 23 (30%) |

20 (26%) |

43 (57%) |

13 (17%) |

20 (26%) |

| P24. Include requirements and arrangements for regular testing and review of animal welfare in disasters plan. | 14 (18%) |

23 (30%) |

37 (49%) |

16 (21%) |

23 (30%) |

Note: Frequencies and valid percentages reported. N/A responses were self-selected. Principle numbering continues from Table 1 and disaster definition (P12), though not discussed here, is included for completeness. Percentages have been rounded.

Discussion

This study examined awareness and implementation of the NPPAD from the perspective of organisations in Australia with a stake in managing animals in emergencies and disasters. Most respondents were from government, emergency services organisations and not-for-profit organisations, they held roles with responsibilities related to animal management and were in direct contact with animal owners. One-quarter of respondents desired more responsibility for animals, and primarily held responsibilities for farmed animals and smaller domestic species (e.g. pets).

Respondent awareness of the principles as a resource for animal welfare planning and policy was moderate, as just over half the sample was aware of them but only slightly more than half had implemented them to some degree. This low level of overall implementation, and the variable level of applying specific principles covered in the NPPAD, demonstrates a clear need to increase awareness and uptake of the principles in many organisations.

At the state level, sound examples of implementation were found in state government planning and processes in Victoria (Victoria State Government 2019), South Australia (Primary Industries and Regions South Australia 2018) and Western Australia (State Emergency Management Commitee 2019). These serve as models for other organisations to consult when adopting the principles into their own arrangements. Importantly, although animal management planning in disasters primarily occurs at state and territory levels, the principles should be widely adopted as a common language by other non-government and private organisations to establish a consistency in Australia’s disaster response planning.

Reported implementation of the NPPAD suggests that despite acknowledging the importance of integrating animal considerations into planning processes and arrangements, there is still a need for animal interest groups and organisations to translate this to practice. An excellent example of this is the Committee for Animal Welfare in Emergencies, a Western Australian operational and policy initiative connecting government (e.g. local) and industry (e.g. agriculture) expertise in coordinating animal support during emergencies (Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development 2019). This also extends to providing local government support for animal emergency welfare planning and response capacity. As survey respondents indicated low recognition of local expertise and resources in this area, actions to improve this are needed.

In both disaster planning processes and plan arrangements, levels of implementation of best-practice communication recommended in the NPPAD varied such as consultation, engagement and accessibility of language. Improved strategic communication about how animal emergency plans are implemented is needed with affected and involved parties and this needs to be provided in easily accessible language (i.e. high readability, minimal jargon). Many animal owners may not understand emergency management and disaster planning and that they hold primary responsibility for their animal’s welfare—an animal emergency management tenet. However, as shared responsibility is also a goal in emergency management, it is essential that planning processes are inclusive and that plans are written and communicated in accessible language. Although preparedness resources for the public are available and written in accessible language (e.g. the NSW State Emergency Service ‘Get Ready Animals’ resources website (NSW State Emergency Service 2021)), it would be beneficial to test the readability and ease of comprehension of disaster plans and descriptions of planning processes with target audiences (e.g. smallholders, horse owners, companion animal owners).

Principles relating to final plan arrangements indicated a need to increase emergency animal planning considerations for the prevention and recovery stages. Respondents indicated a need for increasing formal arrangements for animal support and, although this is seen in animal management functional support structures (e.g. New South Wales Government 2017), non-government organisations can draw on these approaches in disaster planning. Given that this survey captured a convenience sample of Australian stakeholders, findings should be interpreted as a snapshot that is broadly representative of animal management planning and policy stakeholders. However, as stakeholders considered the position of their organisation, findings show specific principles that could be a focus for future research and action.

The NPPAD is an essential tool for the current and future improvement of Australia’s animal arrangements in disasters. This overview of how Australian organisations have adopted them highlights areas for those creating and managing animal welfare plans to implement, adapt and discuss the principles to protect animals from increasing risk.