Research into the human-animal bond in disasters can be used to inform practice and organisation planning and response. A closer alignment of social work and animal services can be addressed by conceptually framing the human-animal bond within theoretical perspectives.

Research highlights that human behaviour is often influenced by our bonds with our animals.1,2 However, disaster and response planning within human service and social work organisations in Australasia has rarely included non-human family members despite high levels of companion animals in households3 and the ethical imperative that recognises animal sentience.4

In 2020, Companion Animals in New Zealand5 estimated that 41 per cent of households included a cat and 34 per cent had a dog. Recent figures from Australia estimated 27 per cent of households with cats and 40 per cent with dogs.6

In social work, animals and humans are frequently seen as 2 distinct domains.7,8 The use of theoretical perspectives familiar to social workers and other human services practitioners can create a conceptual shift in thinking towards a whole-of-system orientation necessary for animal-inclusive disaster and response planning. Ecological and deep ecological theory as well as attachment theory are possible approaches.

Animal-inclusive ecological practice

Social work practice is systemic, using an ecological, ‘person-in-environment’ understanding. People are connected to, and potentially sustained or disadvantaged by, systems beyond themselves. These include family/whanau, community, external structures and processes and identities of gender, culture, belief, sexual orientation and disability. All of these influence our lives.

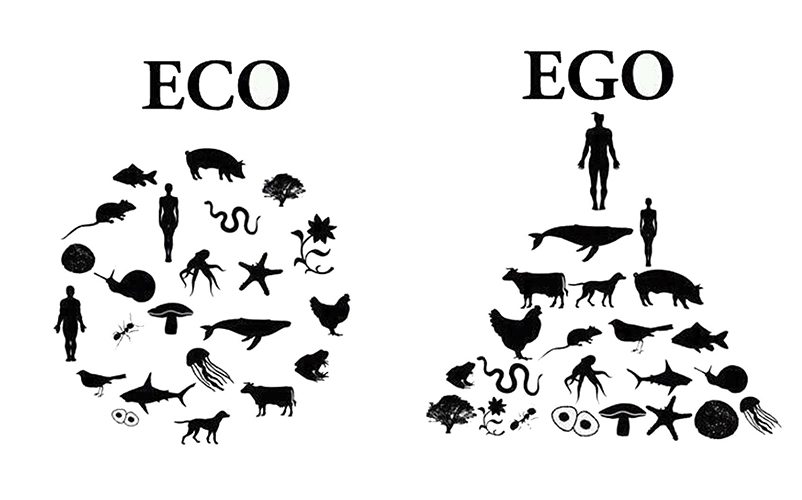

By extending an anthropocentric perspective to a recognition that human beings have mutual interdependence with the living world, theories of deep ecology can be introduced, potentially shifting the social work gaze towards the wider ecology of ‘environment-including-people' (see Figure 1).9 Thus, social work and human service practice can be inclusive of all beings within households and provide an imperative for including companion animals within disaster risk reduction (DRR).

Figure 1: Shifting the ecological gaze.

Image: Reflect for Change.

Human attachment to companion animals

Even without reframing the position of humans within ecological systems, social work practice in planning and response can be informed by people’s attachment to their animals. Social and human services recognise the importance of relationships and that companion animals become integral parts of family life.10 Attachment theory provides a conceptual explanation for how relationships with animals can influence human behaviour in a crisis. Use of assessment skills such as genograms and ecomaps that are standard tools of social work practice can be adapted to include relationships with companion animals within households, families and other living configurations.11

Vulnerable people, vulnerable animals

Attachment theory can be used to identify the importance of animals in the lives of vulnerable and marginalised people who are often disproportionately affected by disasters. Older people and those living with disability or mental health challenges may ‘live alone’ but share their lives with companion animals that provide much needed caring responsibilities and mutual affection. People living without safe or permanent housing may rely on animals for support, warmth, companionship and safety. There are perils to ignoring the centrality of animals in their lives. The considerations of animals within disaster planning may encourage participation by otherwise hard-to-reach families and communities.12

The rationale for animal-inclusive disaster planning

There are several arguments for the inclusion of companion animals in social service planning particularly for emergencies and disasters:

- Having responsibility for animals can encourage people to prepare for disasters as well as assist in their recovery.

- Animals have been linked with peoples’ failures to evacuate in accordance with warnings.

- People are exposed to greater risks if trying to rescue animals.

- People may experience added trauma if separated from their animals.

- Animals can enhance resilience by providing physiological and psychological benefits to people.

- People with poor support networks can be disproportionately affected by the loss of a companion animal in a disaster.

- Significant costs of failing to plan for the wellbeing of animals may arise during disasters.

Organisational responses for animal-inclusive social work

Social work practice can be the catalyst for a shift towards animal-inclusive DRR and this is best supported by systems-level planning for resources and processes to be in place prior to an event. Organisational-level planning can include social work practice activities of:

- instigating animal-inclusive training and education (pre- and post-qualification)

- establishing animal-inclusive assessment forms and processes

- planning or providing animal-inclusive accommodation, animal carriers, leads, etc.

- publishing registers of foster care available for animals that cannot remain with their owners

- establishing inter-agency agreements and protocols for identifying need and allocating responsibility for response animals within households

- maintaining registers of vulnerable people who may need to evacuate with their companion animals (including assistance dogs)

- identifying animals with special needs

- using microchips to identify animals separated from family

- identifying animal abuse and hoarding behaviour when animals are in shelter care.

For social work, animal-inclusive DRR has synergies with other crisis fields such as the interrelationships between family harm and animal abuse. Social work education and practice needs to be animal-inclusive to be truly human.

Endnotes

1. Appleby MC & Stokes T 2008, Why should we care about nonhuman animals during times of crisis? Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science, vol. 11, no. 2, pp.90–97. doi:10.1080/10888700801925612

2. Hunt MG, Bogue K & Rohrbaugh N 2012, Pet ownership and evacuation prior to Hurricane Irene. Animals (2076–2615), vol. 2, no. 4, pp.529–539. doi:10.3390/ani2040529

3. Darroch J & Adamson C 2016, Companion animals and disasters: The role of Human Services Organisations. Aotearoa New Zealand Social Work, vol. 28, no. 4, pp.100–108. At: doi:10.11157/anzswj-vol28iss4id189

4. Aotearoa New Zealand Association of Social Workers 2019, Code of ethics 2019. At: https://anzasw.nz/wp-content/uploads/ANZASW-Codeof-Ethics-Final-1-Aug-2019.pdf.

5. Companion Animals New Zealand 2020, Companion Animals in New Zealand 2020 Report. At: www.companionanimals.nz/2020-report.

6. Animal Medicines Australia 2019, Pet Ownership in Australia 2019. At: https://animalmedicinesaustralia.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/ANIM001-Pet-Survey-Report19_v1.7_WEB_high-res.pdf.

7. Ryan T 2011, Animals and social work: A moral introduction. Palgrave Macmillan.

8. Walker P, Aimers J & Perry C 2015, Animals and social work: An emerging field of practice for Aotearoa New Zealand. Aotearoa New Zealand Social Work Review, vol. 27, no. 1, pp.24–35.

9. Besthorn FH 2013, Radical equalitarian ecological justice: A social work call to action. In M. Gray, J. Coates, & T. Hetherington (Eds.), Environmental Social Work, pp.31–45. Routledge.

10. Trigg J, Thompson K, Smith B & Bennett P 2016, An animal just like me: The importance of preserving the identities of companion-animal owners in disaster contexts. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, vol. 10, no. 1, pp.26–40. doi:10.1111/spc3.12233

11. Walsh F 2009, Human-animal bonds II: The role of pets in family systems and family therapy. Family Process, vol. 48, no. 4, pp.481–499. doi:10.1111/j.1545-5300.2009.01297.x

12. Thompson K, Every D, Rainbird S, Cornell V, Smith B & Trigg J 2014, No pet or their person left behind: Increasing the disaster resilience of vulnerable groups through animal attachment, activities and networks. Animals (2076–2615), vol. 4, no. 2, pp.214–240. doi:10.3390/ani4020214