Volunteers participate in exercises after completion of Level 1 modules. Plans and sub-plans must be exercised, tested and reviewed in peacetime; it is completely inadequate to ‘test’ plans in operational response. Likewise, a rigorous process of debrief and after-action review at the end of the day, end of the shift or end of the response are important contributions to continuous improvement where lessons identified translate to lessons learnt and are implemented by the leadership team. Every incident is different and new lessons are identified and learnt on each occasion. The debrief process is valuable to promote mental health and provides team members opportunities to tell and share their experiences.

Attending a fireground in the immediate aftermath of a fire is physically, mentally and emotionally taxing. Veterinarians often have good counselling skills exercised in their day-to-day practice and this can be a strength, especially when assisting traumatised animal owners. But confronting scenes of hundreds of burned animal bodies, injuries and destruction of property, habitat and environment tests even the most field-hardened. To address this, SAVEM sends groups of volunteers to psychological first aid training, not only to learn how to assist people affected, but to help volunteers manage their own traumas. Support services for volunteers must be available to help address adverse effects of the things that cannot be un-seen or un-heard.

Firegrounds are very dangerous places. People can die or suffer serious injury long after the fire front has passed, and long after a fire is contained. Dynamic risk assessment is a key skill. There are several major fireground hazards that can kill – other than the fire – including falling trees, intensely hot craters beneath a surface crust of white ash and building hazards such as asbestos or stored chemicals or explosives. Even experienced, trained firefighters have died in what should have been benign circumstances but escalated unexpectedly.1 As such, participants must understand that not every animal can be saved and not every animal refuge area is safely accessible. SAVEM has a zero tolerance for participants who disregard safety directives and put themselves or others at risk, or who self-activate. A paramount and positive culture of safety is non-negotiable. Safety on incident ground is everyone’s responsibility, not only the duty of the team leader.

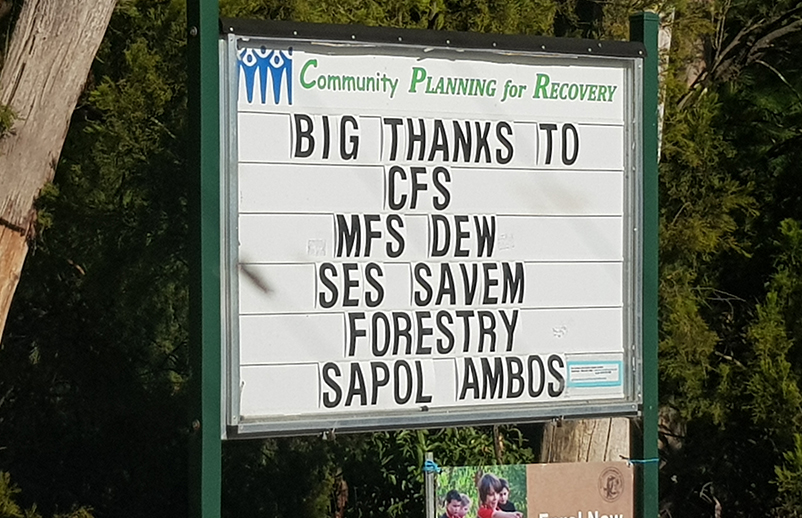

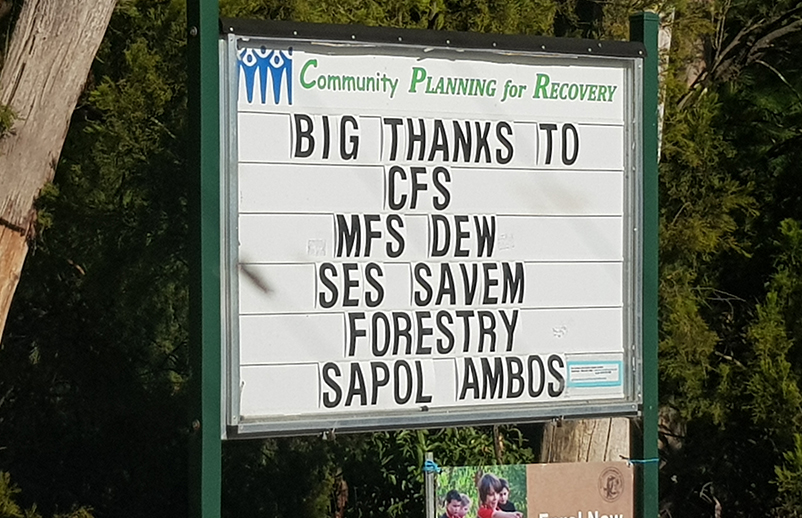

The Scott Creek community notice board after the January 2021 Adelaide Hills fire.

Image: SAVEM Inc.

First – think, act, speak and train in the context of being an emergency service with an animal welfare emergency management remit. A fireground response is nothing like veterinary clinical practice. Typical ‘day job’ skills may not equip volunteers to be operationally adept. It is a mistake to try to replicate a veterinary clinic environment on incident grounds. It is a mistake to come to a response with only an ‘animal rescue’ mindset. There are times when best animal welfare outcomes are achieved by support and monitor-in-situ, rather than removing animals from their habitat and bringing them into care unnecessarily – just because we can. ‘Rescuing’ animals might make humans feel good, but iatrogenic2 morbidities triggered by handling, transport, confinement and ongoing treatment are avoidable: first do no harm!

Forging strong alliances with emergency services first responders is critical. Frontline responders need to be confident veterinary teams will, without exception, operate according to established rules of engagement and respect chain of command. This is why SAVEM trains to the Australasian Inter-service Incident Management System™ (AIIMS™), enabling volunteers to understand and speak the same language as first responders, and to learn how to respond equally well to all hazards.

In South Australia, bushfire is the major hazard of concern for six months of the year, but there are nine hazard types listed in the SEMP that may be encountered. These are urban fire, rural fire, earthquake, flood, extreme weather, hazardous materials, human disease, animal and plant disease and terrorism.

Developing a veterinary emergency management capability does not happen overnight. It takes time and effort to form, maintain and grow an agency such as SAVEM. Government departments cannot do this as the volunteer sector provides operational resources and expertise that reaches far beyond the limitations of government and bureaucracy. The most important asset is having the right people. Veterinary emergency management is not easy and is not suited for everyone. SAVEM volunteers are from varied backgrounds but are like-minded individuals who mesh together and form strong teams and lasting friendships. Our people are improvisers, problem solvers and have a ‘can-do’ attitude.

To achieve best-practice animal welfare outcomes, it is critical for supporting agencies to embed with local emergency services. Volunteers must earn trust, respect and build credibility to become a formal, legislated participant in state emergency management arrangements. Going into a response with only an ‘animal rescue’ mindset is dangerous and won’t achieve access to an incident ground. Having an emergency management approach and an alignment with the emergency services requirements makes all

the difference.