On an ominous afternoon on 12 January 2010, just before 5pm, dogs began barking frantically in Port-Au-Prince, the capital of Haïti. Seconds after, the ground shook as a strong earthquake unleashed chaos and destruction, killing in excess of 240,000 people and an unknown number of pets and domestic animals.

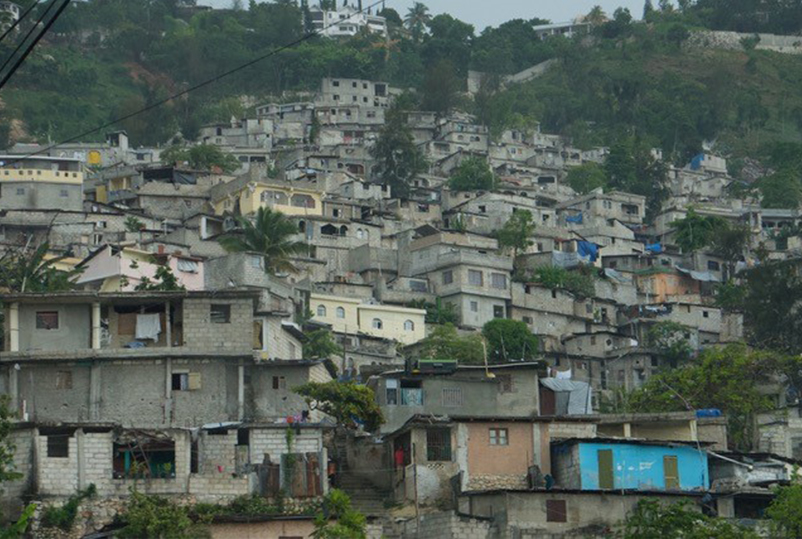

The earthquake brought catastrophic devastation to the city. In Port-Au-Prince, many roofs are made of concrete to protect from the Caribbean sun. When most of them collapsed, thousands of people were trapped, injured or were killed.

While international aid agencies prepared to assist Haïti, the poorest country on the American continent, and readied to dispatch human aid relief, World Animal Protection dispatched a response team 72 hours after the island had been violently shaken.

The cataclysmic devastation in the city was widespread and I knew the team would face challenges not seen before. Our first priority was to coordinate with local animal health authorities and with United Nations representatives to set up mobile veterinary clinics and bring relief to any surviving injured animals. The the team I led was on-site for 15 months and over US$1 million was contributed to the relief effort.

In Port-Au-Prince, many buildings collapsed during the earthquake.

Image: World Animal Protection

Coalition for coordination: To represent animals better before the Government of Haïti, 20 non-government organisations from 2 continents established the Animal Relief Coalition for Haïti Arch to pool resources and maximise the number of animals we could reach and help. Over the 15 months, approximately 70,000 animals were treated and many would certainly have died without the help they received.

Emergency relief: The mobile animal clinics moved continuously from one neighbourhood to another to reach as many communities and animals as possible. The teams helped local authorities with epidemiological surveillance rings when cases of rabies in animals were suspected and worked to prevent the widespread and inhumane use of strychnine to kill dogs. The vets worked with communities to reassure them that help was available for their animals. The mobile clinics were preceded by messengers using megaphones announcing the arrival of the clinic and teams. A long line of people would form with cats, dogs, pigs, cattle, horses and goats waiting for our vets.

Animal health: Two important laboratories and all their equipment at the Department of Animal Health were destroyed during the earthquake. These were rebuilt to provide monitoring of endemic and new diseases and pathogens. We also established a network of cold stations around the capital that were powered by solar energy to allow for biological samples and vaccines to travel safely and be used to protect animal and human health.

Dog census: The first city dog census was carried out to estimate their numbers, zoonoses trends for rabies and leptospirosis and the resources needed for a future healthy dog-human relationship.

Capacity building and awareness: Together with the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction, we trained local veterinarians on how to mitigate disaster risk for animals and also developed a public awareness campaign in the local Creole language. There were also contests at local primary schools designed to reach animal owners with the basics of disaster preparedness and promoting family emergency plans that included pets and domestic animals.

Support communities: To ‘build back better and to do no harm’, we hired all manpower locally as soon as people were properly trained and, where possible, purchased the necessary drugs and medicines from local providers.

Global policy: In an overarching effort to protect animals from disasters, 5 years after the Haïti earthquake, farm and working animals were included by the United Nations member states into the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030.

Haïti’s development and recovery challenges, including its vulnerability to extreme hazards, will require a long-term approach from many stakeholders. Poverty levels are high while governance is still weak in the country, thus presenting mid-term challenges and opportunities for providers of disaster risk reduction and recovery management.

The World Animal Protection team assessed injuries and diseases of animals during the 15 month deployment.

Image: World Animal Protection