Recent events in Aotearoa New Zealand, such as the Canterbury earthquakes in 2010 and 2011 and the Kaikōura earthquake in 2016, highlight the need for comprehensive and inclusive disaster education programs that are geographically and contextually relevant. Disaster risk reduction activities in Aotearoa New Zealand have historically adopted a top-down, expert-driven approach. They have also employed relatively homogenous methods for how communities in New Zealand can prepare for and respond to disasters. As a result, the inclusion of Māori communities and voices within traditional disaster risk reduction planning has been sparse. In addition, there is a lack of preparedness materials for tsunami designed specifically by Māori with Māori community needs front and centre. This paper documents a pilot education project taking an inclusive approach to increasing the knowledge and preparedness of tamariki (children) and rangatahi (youth) in coastal areas of Aotearoa New Zealand that are vulnerable to tsunami. Research was undertaken to develop a toolkit with kura kaupapa Māori (Māori-language immersion schools) and schools located in tsunami evacuation zones in Hawke’s Bay, on the east coast of the North Island. A Māori-led, bi-cultural approach to developing and running the activities was taken. The aim was to create culturally and locally relevant materials for ākonga (students) and kura kaupapa Māori as well as giving ākonga a proactive role in making their communities better prepared for a tsunami event.

A glossary of Māori words is included at the end of this paper.

Introduction

Aotearoa New Zealand is exposed to natural hazards such as earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, floods and landslides (Crozier & Aggett 2000). These hazards are linked to New Zealand’s location on the boundary of the Australian and the Pacific tectonic plates and Ranginui (Sky Father) and Papatūānuku (Earth Mother). The National Hazardscape Report (Officials Committee for Domestic and External Security Coordination 2007) and National Civil Defence Emergency Management Plan Order 2015 (Ministry of Civil Defence and Emergency Management [MCDEM] 2015) identify the most prevalent hazards from a traditional science perspective. Therefore, most mainstream hazard education resources take a similar approach to sharing science knowledge and, in the main, do not recognise Mātauranga Māori. This is despite the extensive knowledge Māori have of their local area and the history of hazards from both the land and from the sea.

Building natural hazard risk awareness, risk literacy and risk management capability is a focus of the National Disaster Resilience Strategy (MCDEM 2019). As such, emphasis is being placed on natural hazards education, particularly within schools.

Most schools in Aoteraoa New Zealand teach the national curriculum and are secular (non-religious). In the late 1980s, kura kaupapa Māori were established to support Māori tamariki and their families to reinforce cultural identity by enabling Māori language and culture to flourish in education. These schools operate fully or partially under Māori custom and have curricula developed to include Te Reo Māori and Tikanga Māori (Māori language and cultural practices). Māori kaupapa (values), Mātauranga Māori (Māori knowledge) and Te Reo (language) are crucial considerations for the development of education resources developed for kura, bilingual and mainstream schools.

The impetus of this research was to develop culturally appropriate tsunami education resources for kuru and schools while also promoting tsunami risk reduction. This Māori-centred research takes a school community-based-participatory approach, framed by qualitative and kaupapa Māori research methodologies and uses a range of data collection methods including interviews, focus groups and surveys. Researchers collaborated with Māori education stakeholders, kaiako (Māori teachers), senior Māori researchers and whānau (family) throughout the project to ensure it aligned with the school kaupapa values and national curricula. The education program applied a tuākana/tēina mentorship Māori teaching-and-learning approach in which high-school-aged ākonga (tuākana) developed tsunami preparedness activities to run with primary-school-aged ākonga (tēina). At the end of the education program, ākonga in high schools were asked to reflect on their participation, what they had learnt and what they had enjoyed during the activities.

Background

Schools play a crucial role in raising awareness of natural hazards, risk and risk reduction among students, teachers and parents (Shaw et al. 2004). In the literature concerning disaster risk reduction, it is suggested the importance of disaster education at school is increasing because:

- children are one of the most vulnerable groups of a society during a disaster

- children represent future resilience

- schools serve as central locations within communities for meetings and group activities

- effects of education can be transferred to parents and the community (Shiwaku 2009).

Tamariki (children) building tsunami resilient structures.

Image: Lucy Kaiser

There are several studies in New Zealand that recognise the value of hazards education programs in schools and the benefits to children who are repeatedly involved in hazard education activities (Ronan & Johnston 2001). King and Tarrant (2013) also suggest that there are numerous benefits of integrated school hazard education programs. These include increased awareness of risks (Mitchell et al. 2008, Ronan & Johnston 2001) and motivating preparedness actions (Shaw et al. 2004).

The literature indicates that knowledge is a key aspect of positive coping. It can assist young people to understand the processes of a natural hazard event and its effects and they can feel less stressed and less out-of-control following such events.

Children’s knowledge of safe practices regarding earthquakes and tsunami was confirmed as a key aspect of their belief that they would be able to cope in the event of an earthquake.

(King & Tarrant 2013, p.24).

Additionally, Peek (2008) argued that programs within schools have the potential for great impact on communities. Additional studies confirm that children who participate in school-based hazards education programs have more accurate knowledge of hazards, reduced levels of fear and realistic risk perceptions compared to their peers (Johnson et al. 2014)

Hikurangi subduction zone and tsunami risk reduction

The Hikurangi subduction zone lies off the east coast of the North Island and poses a significant risk to local communities. From a social science perspective, little is known about how communities relate to and interpret education resources and their correlation to changing preparedness behaviours in relation to earthquakes and tsunami along the Hikurangi subduction zone. As a result, there is ample opportunity for the creation of culturally appropriate and location-specific tsunami risk reduction educational activities for at-risk areas of Hawke’s Bay region (one of the regions most likely to be affected by a large earthquake and tsunami from the Hikurangi subduction zone).

Local tsunami education research activities

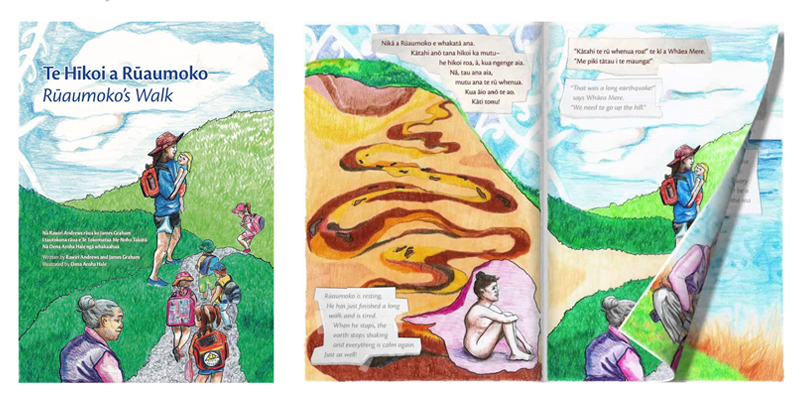

This project was designed to align with two existing programs that were developed in Hawke’s Bay; Me Noho Takatū and Tsunami Safer Schools. Both projects increase the participation of schools and children in disaster risk reduction and increase local knowledge of tsunami risk. While both projects are inclusive of all schools and early childhood education centres in the region, Te Hīkoi a Rūamoko is developed by Māori and places indigenous knowledge and indigenous audiences at its centre.

A multi-year project, Me Noho Takatū ‘Be Prepared’, was developed and piloted in Hawke’s Bay led by the Hawke’s Bay Civil Defence and Emergency Management Group. Through this project, a bilingual pukapuka (book) was produced, Te Hīkoi a Rūamoko (Rūaumoko’s Walk) based on Ngāti Kahungunu iwi (tribe) pūrākau (stories) that relate to earthquake and tusnami warnings and preparedness within their region (Ehrhardt 2014). The project was considered a success for increasing hazard resilience for tamariki, educators and wider whānau. Project materials were received positively (see Figure 1). The pukapuka will be digitised into an interactive medium with animation and informative pop ups.

The Tsunami Safer Schools project (Johnston et al. 2016) was led by the East Coast LAB. The project developed a toolbox for Civil Defence Emergency Management groups to use to help early childhood education centres and schools become tsunami safer schools. Early learning services and schools in Gisborne, Napier and Wellington provided input for the guide. The toolbox includes practice guides and templates for response procedures, guidelines for communicating with families and emergency services agencies, information sheets for parents and teachers as well as guidelines to carry out annual tsunami evacuation walks.

Figure 1: Te Hīkoi a Rūamoko tsunami education project materials.

Image: Courtesy of East Coast LAB

Methodology

This project used a school-based participatory research model so it was important that the school community was involved. The research was structured using discussions in hui (Māori-medium meetings and workshops) with school staff and kaiako and the content and direction of lessons were informed by feedback from the students involved. The project was conducted in accordance with a kaupapa Māori methodology ensuring that the research was designed by and for Māori, addressed Māori concerns, was implemented by Māori researchers and conducted in accordance with Māori cultural values and research practices (Smith 2013). Some of the principles of Smith’s work were adopted and four kaupapa Māori values were identified to determine that holistic long-term community resilience projects contribute to:

- Mōhiotanga (capable): people understand the risks they face and know how to reduce and manage these risks. Participants know what to do and how to help each other in the event of an emergency.

- Whanaungatanga (connected): there is a strong community spirit. People are connected and have relationships with other people within, and outside, their community.

- Manaakitanga (caring): people, families and communities look after each other. They ensure that everyone is cared for physically and emotionally.

- Kotahitanga (collaborative): people, households and communities work together. They reduce their risks together, get ready together, respond to emergencies together and recover together.

Culturally, it was important that, as often as possible, meetings were conducted ‘kanohi ki te kanohi’ (face-to-face). Cultural and educational guidance and expertise were provided by two senior academic mentors who provided peer review throughout the project. To ensure human ethics requirements were followed, a low risk ethics notification was lodged via Massey University for this project (Ethics Notification Number: 4000018005).

Data collection methods included a combination of hui, focus groups, observation and qualitative surveys using a bricolage approach that draws from thematic and content analysis methods (Denzin & Ryan 2007). Evaluation at the beginning and the end of the project was conducted using a combination of informal discussion and surveys. Transcripts and surveys were coded thematically by the research team to develop core themes (Saldaña 2009).

There were limitations to this research. In terms of engagement, only one member of the research team was based full-time in the community, therefore kanohi ki te kanohi (face-to-face) meetings were not possible as often as liked. Additionally, at the outset of the project researchers did not have established relationships and the team had limited time to engage with kura, kaiako and ākonga. As this project was a small pilot project, the team did not conduct a comparative program at different schools in the region to compare and contrast the findings. However, a similar program was conducted with a Kura in Wellington (concluding in April 2020) that used the findings from this research. This project involved a small number of participants and there was little capacity to conduct in-depth quantitative or qualitative analysis that would offer statistically significant data. However, reflections and feedback from participants provided insights for future project iterations.

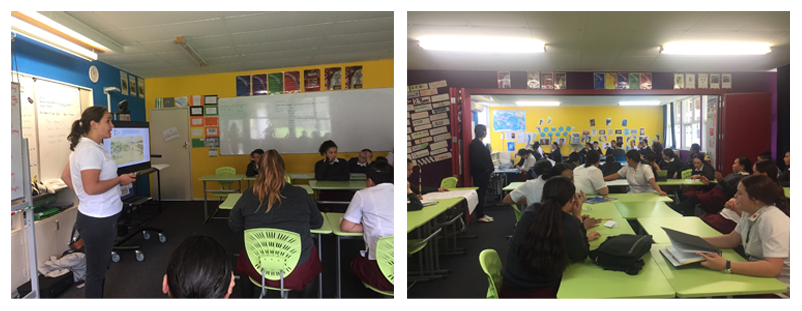

Classroom sessions were facilitated by East Coast LAB.

Image: Lucy Kaiser

Activity design

Before developing the kete of activities, the research team and the principal of the kura wanted to find out what would be most useful for the kura and school communities. To do this, a hui was co-facilitated with kura and school staff to provide specific information about tsunami risk in their community to understand what kaiako already knew about tsunami risk and what activities and knowledge they would consider useful for their ākonga. A focus group workshop with 17 participants including school staff, kaiako, kōhanga reo kaiako (early childhood education teachers) and whānau (family members) was carried out with guided group discussions of a series of thematic questions. Participants were asked what activities their ākonga found most engaging. A range of activities was identified such as waiata (songs), drawing, creative writing, physical activities and art. These were included in the activity design to reach the broad range of ākonga.

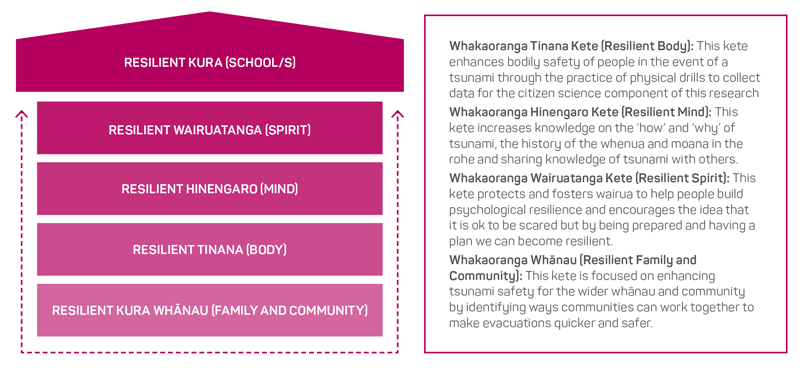

The structure of the activities was framed using a Te Ao Māori kaupapa framework, a holistic approach to tsunami resilience adapted from Durie's public health model, Te Whare Tapa Whā (Durie 1994) that is addressed in the kura curriculum. In order to support tsunami resilient communities, the kura and the school community filled four kete (baskets) with contextually appropriate activities that improve tsunami awareness, preparedness and knowledge (see Figure 2).

The five learning sessions consisted of several modules to learn more about tsunami and tsunami preparedness as well as interactive activities including creative writing, singing, drawing and group discussion. Mātauranga Māori (Māori knowledge) and Māori kupu (words) were integrated into the sessions. The first four sessions were conducted in the classroom of the high school ākonga while the fifth and final sessions included a visit to the primary school to run the activities that the ākonga had designed. While the initial lesson plan framework was created in collaboration with the kaiako and the kura staff, the ākonga informed the content of the lessons and had autonomy for designing and facilitating their tamariki activities. At the conclusion of the two-week program, the high school ākonga completed a survey and reflected on what they had learnt.

Figure 2: Whakaoranga Kura (resilient school) framework.

Findings

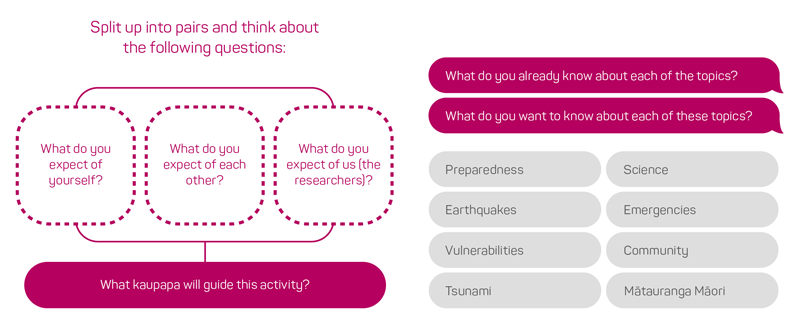

Student pre-program exercise

An activity was conducted at the outset of the sessions with the ākonga to benchmark what they knew about tsunami, what they were interested in learning about and what their classroom rules would be (see Figure 3). The evaluation was run in groups of two for discussions that was followed with classroom discussions. Responses from ākonga were recorded on large pieces of paper that were revisited at the conclusion of the classroom sessions to stimulate reflection.

In terms of what ākonga already knew about tsunami, there was limited knowledge of how tsunami occur and the science behind them. Additionally, awareness about civil defence messaging for tsunami such as ‘if it’s long and strong get gone’ and what to do in the event of a tsunami was low among the ākonga. Earthquakes were mentioned frequently by ākonga, which may have been due to experience of semi-regular earthquakes of moderate size in the region (Becker et al. 2017, p.4), prolific media attention on the 2010, 2011 and 2016 earthquakes (Carter & Kenney 2018) or regular public and school-based campaigns on earthquake preparedness. Confidence of ākonga discussing mātauranga Māori and using Te Reo was also mixed with some ākonga happy to discuss pūrākau (oral histories) and speak in Te Reo, while others were more reluctant.

Figure 3: Pre-program exercise questions.

Student post-program reflections

The high-school-aged students (N=31) completed a short survey evaluating the education program. There were three open-ended questions used to understand the ākonga thoughts and reflections on the activities and to improve the development and facilitation of future kura-centred tsunami education activities. The questions were:

Q1-What is something new you have learnt about tsunami over the last five sessions?

Q2-What is something you have learnt while designing and carrying out your activity with the tamariki?

Q3-What was your favourite part of the project?

Several ākonga addressed multiple points in a single answer while others responded to one or two of the open-ended questions.

Q1-What is something new you have learnt about tsunami over the last five sessions?

Ākonga discussed a range of tsunami-related learnings particularly in the civil defence and preparedness realm. Answers included that they knew ‘to go inland or to higher land’, ‘if an earthquake is long and strong, get gone’, ‘our school would have less than 30 minutes to evacuate in the event of a near-source tsunami’, ‘we need to have a family discussion about emergencies’, ‘do not wait for tsunami sirens’ and ‘what to have in a survival kit (only the necessities; torch, radio, medication)’. Ākonga were also aware of the location of evacuation zones; what the different colours meant on evacuation maps and where they could find maps online. Much of the civil defence and preparedness information was disseminated in the form of interactive activities and discussions as opposed to lectures. As such, the experiential nature of these activities could be a potential contributing factor for ākonga retaining this knowledge.

Q2-What is something you have learnt while designing and carrying out your activity with the students?

Student answers to this question were largely focused on group dynamics and their interactions with the younger students. Respondents discussed their ability to work in groups and be productive when they weren’t supervised: ‘it wasn’t as easy as it may seem to teach [tamariki] new things’ but ‘once you’re organised and ready it’s easy to teach children’, ‘[tamariki] love giving things a try’ and that they ‘listen well and would act quick if there was a tsunami’. Thay also reported that ‘[tamariki] learn easier through hands-on activities’ and that it was ‘important to make activities interactive’. Some ākonga who were initially reluctant to work with younger students reported that tamariki are ‘really nice to work with’ and they enjoyed the experience.

Q3-What was your favourite part of the project?

The majority of all responses showed that the trip to the school to teach the tamariki the activities was their favourite part of the project. Many of them enjoyed meeting the tamariki and expressed a wish to return to the school in the future for another activity. One ākonga reflected that these activities were important because it showed that ‘we should take things seriously for younger ones’. Several ākonga identified that learning and teaching the tsunami rap to the ākonga and performing it as a big group was a highlight for them and they were proud to see the results of their work.

This feedback was useful for understanding participant thoughts on some of the research outcomes. However, feedback was not analysed in-depth for themes due to the short and informal nature of the survey and the small number of participants. Still, it gives a broad understanding of the ākonga’ reported experiences. Formal evaluation of the primary-school-aged tamariki did not occur as it was not within the approved ethical parameters of this project. Kura staff indicated that tamariki found the activities enjoyable, however, a single session was unlikely to make a significant impact on their personal tsunami resilience.

Reflections

Classroom management was a challenge due to the number of ākonga and the amount of semi-unsupervised group work that meant it was hard to keep everyone on track. The support of the kaiako was extremely helpful to maintain order in the classroom. For future iterations of the program, a smaller group size is recommended.

Time management was also difficult, The initial lesson plan was developed in collaboration with the kaiako to comply with the classroom curriculum and to be responsive to what the ākonga reported they wanted to learn. However, all planned activities could not be conducted across the first few sessions as more questions were raised than anticipated. It was clear that the lecture style of presentations was not very engaging for some of the ākonga. This was anticipated to some degree based on feedback from the kura hui as well as by previous experiences working with ākonga. Future lessons would benefit from a balance of presentations and interactive activities.

Finally, for ākonga-run activities, the groups prepared at different levels and, as multiple activities were run concurrently, it was hard to maintain structure and order as well as provide assistance to each group. Better planning and supervision of the groups, as well as backup activities to keep everyone engaged, is required. Fortunately, the tsunami rap could be adapted for any group size so ākonga who lost focus could be directed to join this group and contribute.

Including kura kaiako and staff in the development and implementation of education activities is crucial to the success of such projects. It is important to engage members early and often to ensure that activities can be accommodated into school calendars.

Conclusions

The reflections provide guidance to the suitability of the four holistic outcomes as aspirations for future programs as well as what resonated with ākonga. In terms of mōhiotanga (capability), what to do in the event of a tsunami and preparedness actions were front of mind for many of the respondents. Further research into the reasons why this information resonated with ākonga could reveal motivations to act. In terms of whanaungatanga (connectedness), many of the ākonga were ex-pupils of the kura or had younger siblings. There was an observed enthusiastic performance of waiata and haka at each of the schools, which indicated a sense of cultural pride and connection. In terms of manaakitanga (caring), some of the ākonga discussed feeling a responsibility to ensure that tamariki are safe in the event of a tsunami and saw fostering resilience for others as important. In relation to kotahitanga (collaboration), this was facilitated through group work and working with both schools. Based on the desire of some of the ākonga to return to the kura (and the kotahitanga that already exists between the schools), there are opportunities for further work using a tuākana/tēina model for increasing tsunami preparedness.

This project was small in scope but offers opportunity for work in this area with the same or other schools to develop tsunami activities that embrace Māori kaupapa and bi-cultural learning. This aim is to enhance the resilience of our coastal communities, schools and students to tsunami and other natural hazards.

Glossary

| Te Reo Māori | English |

| Ākonga | students |

| Hīkoi | to walk, trek, journey |

| Hui | to gather, congregate, assemble, meet |

| Iwi | tribe |

| Kaumatua | elder - a person of status within the whānau |

| Kai | food, to share a meal |

| Kaiako | teachers |

| Kanohi ki te kanohi | face-to-face, in person |

| Karakia | to recite ritual chants, say grace, pray, say a blessing |

| Kaupapa | topic, policy, purpose, matter for discussion |

| Kaupapa Māori | Māori approach, Māori topic, Māori customary practice, Māori institution, Māori agenda, Māori principles, Māori ideology; a philosophical doctrine, incorporating the knowledge, skills, attitudes and values of Māori society |

| Kawa | specific karakia and customs for the opening of new houses, canoes and other important events |

| Kete | basket, kit |

| Kia Takatū | to prepare, get ready (people) |

| Koha | Gift, contribution |

| Kōhanga reo | early childhood education centre that uses Māori kauapa values, tikanga, kawa and aspirations to guide their practice |

| Kōrero | discussion |

| Kura | school |

| Mahi | work, accomplish, practise |

| Mana | prestige, authority, influence, status, influence |

| Māori | Indigenous people of Aotearoa New Zealand |

| Mātauranga Māori | Māori knowledge - the body of knowledge originating from Māori ancestors, including the Māori world view and perspectives, Māori creativity and cultural practices |

| Mihi | to greet, pay tribute, acknowledge, thank |

| Rangatahi | younger generation, youth |

| Rūaumoko | a Māori ancestor with influence over earthquake, volcanic and geothermal activity |

| Rohe | area of land, boundary, territory, |

| Rōpū | Group, committee |

| Parawhenua | the personified form of the waters of earth, associated with tsunami |

| Pukapuka | book |

| Pūrākau | cultural stories passed down through ancestral lines |

| Tamariki | children |

| Tangata Whenua | Indigenous people - people born of the whenua (i.e. where the people's ancestors have lived and where their placenta are buried) |

| Te Ao Māori | a Māori worldview |

| Te Reo Māori | Māori language |

| Tēina | younger brother, sister |

| Te Whare Tapa Whā | a model for understanding Māori health |

| Tikanga | customary protocols - the customary system of values and practices that have developed over time and are deeply embedded in the social context |

| Tuākana | elder brother, sister |

| Waiata | song |

| Whakapapa | genealogy, lineage, descent |

| Whānau | extended family |