Griffith University researchers have partnered with the Office of the Inspector-General Emergency Management to develop a community-of-practice across Queensland to build community-based food resilience at the local level.

Severe weather events pose significant risks to food supply chains that rely on transport infrastructure such as road and rail. Empowering individuals and communities to exercise choice for their self-reliance and take responsibility for the risks they live with is a priority action in Australia’s National Strategy for Disaster Resilience.1 This requires local resilience-based planning that anticipates actions across the prevention-preparedness-response-recovery spectrum.

Gaining knowledge of the community’s long-term needs and tools for managing their risk to exposure is central, as are creating partnerships that are inclusive of communities with the relevant agencies and organisations.1 As disaster risk management practitioners, we know this is important. However, do we relate this imperative to our relationship with food?

This call to action for community-based food resilience is based on findings from consultations in 2011 and 2018. Consultations were conducted with practitioners concerned with building community self-reliance around food provision. Despite the span of almost a decade, both cohorts provided similar and valuable insights; identifying immediate practical needs identified from working directly in disaster resilience and local food initiatives.

The first set of findings were drawn from interviews conducted immediately following the Queensland floods in 2011.2 Analysis resulted in five findings, as well as insights and recommendations, to aid policy practitioners seeking to develop food-related disaster resilience at the community level.3 The second set of findings arise from two jointly-hosted practitioner workshops held in 2018.

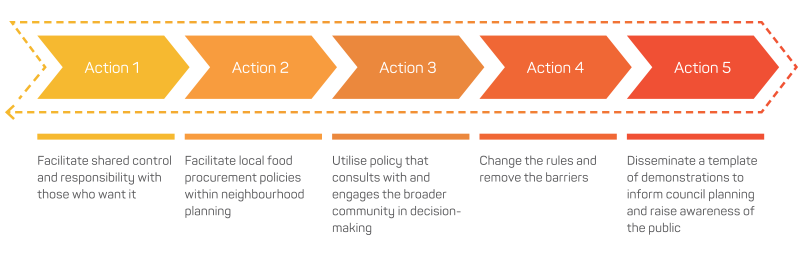

Synthesising the 2018 workshop insights with the 2011 findings, a straightforward, five-step action plan for practitioners ‘closes the loop’ on meaningful community action for local food contingency planning. Figure 1 shows the five-step plan.

Figure 1: Actions to close the loop for enabling local food contingency planning.

Source: Reis 2019

Action 1: Facilitate shared control and responsibility with those who want it

‘Individuals and communities are the starting point to build disaster resilience and the way to work with communities is to connect with what is already there.’4 It is important to tap into the human desire to express goodwill, connect with existing capacities in the community and harness the power of successful precedents. There is no need to reinvent the wheel, rather, community members need to know that they have permission to participate and express their goodwill.

Action 2: Facilitate local food procurement policies within neighbourhood planning

‘Engaging a community in how it can prepare for, respond to and recover from emergencies is more likely to result in decisions and outcomes the community is confident about and will act upon, and this in turn will support the work of emergency management organisations.’4 An increasing number of local food procurement policies can provide options for neighbourhood planning processes that address local conditions, needs and aspirations. Examples for local food procurement strategies include:

- People’s food plan (Australian Food Sovereignty Alliance 2013)5

- Food-sensitive planning and urban design (Heart Foundation 2011)6

- A Future for Food (Public Health Association Australia 2012)7

- Paddock to Plate (Campbell 2009).8

Action 3: Utilise policy that consults with and engages the broader community in decision-making

Knowing that ‘one-size’ solutions do not address the needs of all contexts and circumstances, the key approach to emergency and disaster management is engagement with communities. The Community Engagement Model for Emergency Management, detailed in Australian Disaster Resilience Handbook 64, is guided by three overarching principles:

- Gauge the capacities, strengths and priorities of local communities such as their knowledge, experiences and existing networks.

- Acknowledge that communities are different and have varied perceptions of risk.

- Partnering with communities to support existing networks is contingent on mobilising the ‘strategies that empower local action’.

Action 4: Change the rules and remove the barriers

An acknowledgment of the different perceptions of risk within communities necessitates ‘identifying and addressing barriers to engagement’.4 This includes internal barriers within government that produce policy and behavioural inflexibility to community innovation, participation in and distribution of locally-sourced food. This requires relaxation of legislative and policy constraints during and after severe weather events. For example, farmers being locked into exclusive contracts with corporations whereby food is physically available but contractually unavailable. Organisations need to be ‘flexible enough to use knowledge to adapt to emerging situations. Learning may be difficult, but it is often unlearning that we really struggle with’.9

Learning organisations require ‘purposefully modifying behaviour to reflect new knowledge and insights’, which entails ‘amending the existing way of doing things’.9 Local councils have demonstrated creative capacities to do that in relation to ‘street-curb’ gardens. Once considered as ‘guerrilla gardening’ (the illegal activity of gardening on public land such as footpaths) gardening is now a legitimate activity through the creation of Verge Garden Guidelines. These guidelines allow individuals and communities to grow edible produce between the property boundary and the road kerb, for example, Brisbane City Council (2019).10

Action 5: Disseminate a template of demonstrations to inform council planning and raise awareness of the public

‘Stakeholders need to be encouraged to share their potential lessons.’9 Identifying and showcasing projects is an essential tool to raise public awareness of what can be done. Disseminating the achievements of local food visionaries and early adopters has good potential for building momentum. A focus for this is to build a business model for accessing locally available food. This includes local communities and businesses having business-based approaches to local food contingency plans. Formalising these arrangements can facilitate shared control and responsibility with those who want it – thus closing the loop.