Abstract

In 2009, four major bushfires destroyed vast areas of Gippsland in eastern Victorian including the areas around Delburn, Bunyip, Churchill and Wilsons Promontory, and are collectively known as the 2009 Gippsland bushfires. This paper explores how young adults in the rural areas are recovering from these bushfires and what psychosocial supports they perceive assists their recovery. A diversity of recovery experiences and needs were expressed reflecting that young adults are not a homogenous group. However, there were commonalities in their stories and they described the bushfires as being the most defining moment of their lives. Participants also reported low engagement with recovery supports, being ‘out of the loop’ when recovery information and support was distributed. Because young adults are often in the process of moving to or from the area because of life transitions such as relationships, jobs, study, or travel, participants reported exclusion from ‘placebased’ recovery supports. They reported ongoing emotional and physical health issues and exacerbation of chronic illness that had not been sufficiently acknowledged. Despite challenges in accessing important recovery supports, young adults in this study are moving forward with hope and optimism.

Introduction

Australia experiences extreme weather events and repeated natural disasters. The region of Gippsland in eastern Victoria is prone to flood and drought and is an at-risk area when it comes to bushfires (Department of Sustainability and Environment 2009). In January and February 2009, southeast Australia experienced the most severe heatwave in recorded history (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2013, Australian Medical Association 2008, Department of Human Services 2009, Teague, McLeod & Pascoe 2010). The last weeks of the heatwave coincided with the Black Saturday bushfires on 7 February 2009, which killed 173 people, injured over 800 people and adversely affected many others (Teague, McLeod & Pascoe 2010). These fires provide the background to this research with a focus on the Delburn, Bunyip, Churchill and Wilsons Promontory bushfires. This study is part of a larger study exploring young adults in these areas and their longer-term recovery.

There is a paucity of literature defining recovery from the perspective of young people and so it is important to glean young adults’ specific recovery perspectives and journeys. ‘Personal recovery’ here refers to an ongoing, holistic process of individual growth, restoration and self-determination following a traumatic event (Slade 2009, Onken et al. 2007). Stories from young adults of loss and dislocation following the 2009 bushfires were complex, nuanced and fluid; reflecting the liminal predicament of young adults at this age. Of note, there were some commonalities. All participants indicated acknowledgment as a key factor in their recovery.

Methodology

This research was exploratory and was informed by social constructionism, which views the world as being produced and upheld through processes of social interactions (Creswell 2013). It is an appropriate methodology for exploring complex areas such as the recovery of young adults, where there has been little first-hand research (Creswell 2013, Braun & Clarke 2013). There is a reflexive interplay between intentional acts such as the language’ used in stories that are the source of social reality and the social reality that, in turn, informs these intentional acts. As Drevdahl (1999) puts it, ‘language speaks as much as we speak it’ (p. 1). In other words, language socially constructed, in turn, socially constructs. Further, recovery is progressively seen as a social process (Marino 2015). The exploration of these recovery experiences was filtered through the lens of language, rural location, and the current state, national and global recovery frameworks. This epistemology provided an understanding of the personal constraints and compounding issues that may influence young rural adults during their recovery.

Method

A purposive sample of young rural adults aged 24-34 affected by the 2009 Gippsland bushfires was used. The 24-34 cohort was chosen as it has been underrepresented in previous research studies (Durkin 2012, Grealey et al. 2010).

The research data was constructed from data collected via a qualitative online survey and in-depth audio recorded telephone interviews with transcripts analysed using qualitative thematic analysis. Socio-demographic data collected included gender, age at the time of the 2009 bushfires, current age, where participants considered home to be, the postcode at the time of the bushfires and any relocation due to the bushfires. The qualitative survey and interview questions included bushfire exposure and effect, recovery social networks and supports, community attitudes and support, information exchange and communication, physical health, mental health and wellbeing, personal growth and any final thoughts.

Ethics

This research was approved by Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee. All publicly available information about the participants is anonymous and is confidential. Names and identifying information were not used in the data analysis nor in the final report. Names and identifying features such as a specific place of residence were excluded. Participants were allocated pseudonyms.

Participation process and procedure

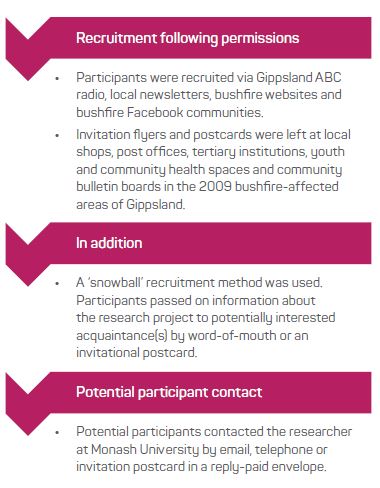

The recruitment process is outlined in Figure 1.

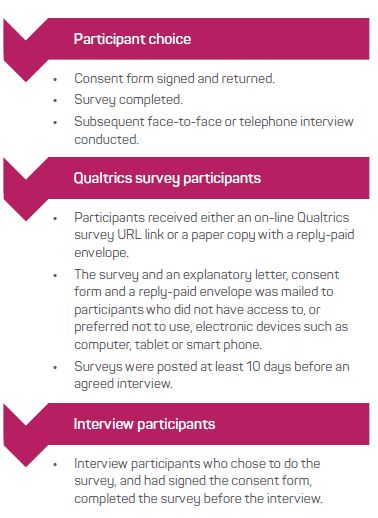

As a result of the broad call for participants, 20 respondents participated. Figure 2 summarises the participation procedure.

Figure 1: Recruitment summary

Figure 2: Participation procedures.

Thematic analysis

Thematic analysis followed Braun and Clarke’s (2013) six-phased approach. Specifically, the thematic analysis comprised of creating the initial report through familiarisation with the data generating initial codes, identifying the themes, reviewing the potential themes, naming and defining the themes and a final thematic analysis, discussion and write up. This approach was not a linear process. Rather, it involved traversing back and forth throughout the data.

Six themes emerged from the analysis of the data. The themes align with and were organised according to the five interlinking recovery processes described in the existing CHIME personal recovery framework of Mental Health Coordinating Council (MHCC): connectedness, hope, identity, meaning and empowerment (Leamey et al. 2011). The CHIME framework provides a useful matrix for the personal recovery research efforts in this study. Both personal recovery and the wider social context of participants’ lived recovery experiences coincided with many aspects of recovery for young adults using the modified Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service (MHCC 2015, 2016) model. Modifications to CHIME definitions and language advocated by Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service (2015) and the MHCC (2016), also reflected most of the participant language used in the surveys and interviews. From the

data, a further theme, ‘acknowledgment’, was identified as a sixth overarching theme. This sixth theme is key to participant engagement with psychosocial supports and their recovery and is the focus of this paper.

Results and discussion

Young adults talked about the 2009 Gippsland bushfires as being the most defining moment of their lives. All said that they felt unfamiliar in their previous home environment due to the loss of the physical reminders that anchored them to place, and they expressed a sense of losing their ‘whole lives’ including their childhood. Recovery effectively occurs in the context of community and personal relationships where the reality and the unfairness of traumatising events are acknowledged (Xu et al. 2015). Tamsin said ‘feeling as though your story has been heard, understood, [helps recovery]’. The theme of acknowledgment underpinned all CHIME recovery themes.

Acknowledgment

Meuller and colleagues (2009) define ‘acknowledgment’ as a social understanding of a person’s unique experiences. Social, in this context, refers not only to family and friends but also to service providers, workplaces and community. In the recovery literature and information, it is directed towards and is about young adults. Social acknowledgment, as a concept, includes social acceptance, peer pressure and judgements (Maercker et al. 2009). It can also impact on illnesses such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Meuller and colleagues (2009) found ‘that disapproval from family and the social environment was related to higher PTSD symptoms’ (p. 160). Further, Maercker and colleagues (2009) determined that social acknowledgment should be viewed as a protective factor for PTSD symptoms because a higher level of social acknowledgment was associated with fewer PTSD symptoms. Acknowledgment appeared as a powerful theme and even more so because in all cases, young adults in this research said it was the single most important way that their recovery could be improved.

According to Gibbs and colleagues (2016) the protective, affiliate and affirmative role of relationships, connectedness and acknowledgment of trauma performs a positive role in promoting resilience and recovery. The aspect of acknowledgment was interwoven through all participant stories and underpinned all CHIME themes. Young adults said they were disempowered due to lack of consultation and acknowledgment of their particular needs. Participants commented on several factors that led to unacknowledged needs. A recurrent theme was the importance of understanding, acknowledgment and validation both by others and of their own feelings through the opportunity to tell their story. As Karen stated, ‘I think the more that you tell a story the more it…becomes your truth…and so in that way I think telling the story is really helpful and validating’. Felicity also recognised that talking and being understood was essential to recovery. She commented:

Just talking is the main thing in recovery! It is important to have someone to talk to who understands, and our family is quite close so we spent the whole time together. I was lucky to have supportive parents, and my sister and a new business to distract me.

Felicity

In contrast, Karen felt that because she had not had a forum to tell her story, her experience was ‘unacknowledged’ and was ‘illegitimate or false’. She explained:

I didn’t want to be in the way. I didn’t talk to anyone, not my mum or partner or anyone for a few years. Now I am angry enough to start to get some help. I understand that for some people telling their story might be harmful and bring things up or that they might ruminate on the negatives, but I feel that I have not had a forum to tell my story so it feels illegitimate and false. It feels like it didn’t really happen.

Karen

Later, after the interview, Karen commented that telling her story via the interview process offered, ‘an opportunity over repeated telling to validate and understand [her] experience of the fires’. In all instances, the participants considered that others seldom acknowledged the trauma they experienced or their subsequent support requests.

Overlaying this, because they were not commonly property owners, participants said they were disadvantaged when it came to receiving a fair share of recovery supports. Beth commented on this sense of inequity, saying, ‘I gained some support, but was overlooked for most. Everything went to my parents first, because they were officially recognised as having lost their house, whereas I was not’. Adam said, ‘I think that if you didn’t have your house burn down then your pain is seen as less important’. Laurel reflected, ‘[I wanted] acknowledgment that I suffered and lost the same as my parents and others’.

Participants cited that a lack of acknowledgment of their needs led to being ‘overlooked’ and therefore inequities in distribution of recovery resources. Laurel’s following point of view about young adults’ inadequate access to recovery resources and information reflects the final reports on the 2009 bushfire access and distribution of psychosocial recovery supports (VCOSS 2012, Grealy et al. 2011, DHS 2009). Laurel commented:

A lot of people were extremely dismissive of the young adult demographic and what they were entitled to. I know a lot of funding was handed out to households; it might’ve just been one adult per household. So, parents or under 18 got quite a bit of support but between 18 to 35 years old there was a massive hole where information was just falling through gaps, and it was like that demographic was forgotten, and then when people did try and advocate for them a lot of people were very dismissive.

Laurel

Because of their age and financial dependence on parents, young adults said they were often ineligible for support services, such as case management and material aid. Laurel concurred with others on the general lack of support, commenting:

I gained some support but was overlooked by most. Equity? Barely at all. Not for my age. I had to seek out and pay for my own professional support.

Laurel

William said:

Young adults were definitely missed when it came to funding, psychological support, Blue cards and case management. It felt like there was nothing available.

William

The objective of the Victorian Bushfire Case Management Service was to facilitate access to services, grants and information and to assist recovery. One case manager was allocated per household not to children or young people. Case managers worked with parents to support all members of the family. This was aimed at supporting the integrity of the family unit, particularly post-disaster, where supporting parent confidence and capacity can be important aspects of the work (Hawe 2009). Many young adults relocated elsewhere after the bushfires and were not living with their family and missed out on this support. Young adults who left the bushfire-affected area said that their ongoing predicament was unacknowledged.

Young adults in this study said that they were silent in order to protect their parents from further stress. Mary explained that she wanted to shield her family from her own distress, ‘because they were already stressed and I did not want to add to this stress’. Laurel concurred, saying, ‘yeah, young adults were not talking in order to protect their parents from further stress, this is what I did and this is what I heard others did’. Participants recognised that this behaviour reduced their voice, meant their needs were not acknowledged and further disempowered them. Inevitably, this abnegation of voice contributed to lack of acknowledgment.

If young adults are not acknowledged for their specific loss and needs then they may be left adrift from essential recovery supports. Jack’s opinion was that young adults’ needs were sometimes overlooked because the community failed to acknowledge their vulnerability. He pointed out that those who were independent with limited social networks did not always have the capacity to source the support they needed after the bushfires.

Jack explained:

I don’t think there is an issue with the community’s attitudes or support towards young adults. It is probably just the lack of awareness that community needs may be so varied and that young adults’ needs are different to [older] adults. Young adults’ abilities to be proactive, make good choices, cope with stress and have positive role models can be all over the place from person to person, and after disasters, have potential to leave them helpless unless looked out for by other grown-ups. Probably just recognising that age group for its vulnerability and needs is the biggest thing. Further, those who were independent would have had to source [support] information. I know a few that didn’t do that and basically got no support. It makes it harder if you had very little or no social networks in the affected community.

Jack

Tamsin said that the recovery process needs to be non-judgemental and accepting of the effect of different experiences and recovery rates for young adults. Tamsin felt strongly that it was important to acknowledge everyone’s experiences without judgement. She pointed out that it is not simply the loss of property that leads to a sense of grief and strong emotional response. She said there is a need to:

Reiterate at school, work, home, groups etcetera that ANYONE is allowed to feel grief, sadness, anger etcetera about these fires for as long and as deeply as they need to. I saw first-hand a person telling another off for being so visibly affected because they didn’t lose their house or family.

Tamsin

How young adults are recovering

Despite the reported lack of acknowledgment of their needs and the consequent deficits in psychosocial supports, all young adults in this research demonstrated resilience, initiative, creativity and a capacity for posttraumatic growth. Nonetheless, when asked how they were recovering from the Gippsland bushfires, the majority reported that although there was a lengthy time when they were ‘not OK’, they were now doing ‘OK’. The term ‘OK’ informally means, ‘satisfactory but not especially good’ (Oxford Dictionary 2017). It is worth noting that in their responses to the survey, many participants described their physical and emotional health as being ‘good’ but not ‘very good’. Five out of 20 young adults in this study reported having medically diagnosed PTSD. Six participants reported poor physical health in the aftermath of the catastrophic event. In addition, three participants cited exacerbation of their chronic illnesses.

When asked what would have improved recovery, they all said it would have helped to be acknowledged as independent adults who needed advocacy and support; that it would have helped to have access to case managers and material aid and better access to appropriate and affordable psychosocial support in general. Most importantly, participants commented that they wanted to be recognised and acknowledged as suffering the same trauma as their parents and others in the community and entitled to the same recovery supports.

In coming to terms with the bushfires, most participants said that despite the fact that the bushfires had left them with an emotional and sometimes physical imprint, they had grown personally because of the bushfires and felt they were wiser, stronger and had a greater appreciation of life. Tamsin’s view of her present life was upbeat and optimistic and she demonstrated an awareness of how the disaster has imbued her with strengths and given her capacities that she offered to others:

Sometimes it takes a horrible event like that to kind of show what weaknesses are currently apparent in emergency situations and subsequent generations can benefit from events like that … My experiences offered me advantages in my career where I gained ‘cred’ and respect from others in the bushfire industry, within which I continued to work, and still do. I think I’m doing extremely well. Obviously it’s still a part of my life. However, for such a horrible situation to go through, I’ve turned it into positive, the best positive outcome possible, and then used it as leverage to make me resilient.

Tamsin

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. Firstly, coding and theme development requires a reflexive process and it inevitably imposes the researcher’s imprint on the data analysis (Denzin & Lincoln 2011). Nevertheless, participants could choose to either answer or not answer the questions, so the focus on certain aspects of their individual recovery remains largely self-driven. Secondly, the generalisation of the socio-demographic aspects of this study has limitations due to the relatively small sample size. While the findings of this study may not necessarily be generalisable to other young adults who have been subjected to a catastrophic event, the study offers an important insight and may be of use to other service providers, policy makers and researchers. In addition, a salient feature of qualitative study is that the number of participants is often small. Scale is not crucial in qualitative studies and there is no need for estimates of statistical significance because the number of a phenomenon may only occur once in order to be significant (Braun & Clarke 2012).

Conclusion

Acknowledgment was a pivotal and overarching theme that emerged and the key missing factor that young adults said would improve their recovery. Acknowledgment means listening to young adults’ stories, gaining an understanding of their predicament, consulting with them and validating their needs. It also means acknowledging that young adults are not a homogeneous group and recognising that young adulthood is a particular developmental stage. The current focus of community recovery models on ‘placebased’ and ‘on-the-ground’ recovery activities meant that this mobile and transitional cohort of young adults was often left to their own devices once they left the area. A recommendation of this study is to enhance localised disaster recovery responses by outreach to young adults who have relocated elsewhere.

Young adults in this research reported that not having their recovery needs acknowledged meant they felt disconnected from important psychosocial recovery supports. Listening to young adults’ stories is an important part of understanding and acknowledging their particular experiences and consequent needs. An imperative for recovery responders is to listen to young adults’ stories and for support services to facilitate their engagement.

To help young adults, community planners must develop ways of providing access to supports that acknowledges their longer-term recovery needs. This research suggests that acknowledgment could be considered first in the CHIME personal recovery process so that losses and predicaments of young adults are validated. It is recommended that further research examine the utility of expanding the CHIME process to include ‘acknowledgment’.