Stakeholder engagement is an important part of planning for emergencies and disasters. This paper describes and discusses the processes of engagement, particularly information sharing, between local government disaster managers, land-use planners and the developer of a large master-planned community in Logan City in South East Queensland. Due to its large scale and importance for the local economy, this development has been designated as a Priority Development Area by the Queensland Government, meaning that approval processes are managed by the state rather than the local government. This study found that local disaster managers are keen to promote strategic disaster planning by improving their engagement with state-level planning, development and assessment processes governing priority development areas. Collaboration with local ‘place managers’ emerges as a potential way forward. A better understanding of the roles, responsibilities, accessible information and opportunities for collaboration across stakeholders and between disaster management and planning frameworks can facilitate improved outcomes for emergency and disaster management.

Introduction

Strategies for population and urban growth management in South East Queensland include the development of large, residential master-planned communities (MPCs) within the region’s peri-urban (urban fringe) landscapes (Queensland Government 2017a). Some of these are designated by the state government as Priority Development Areas (PDAs) that streamline land-use planning and assessment processes and, in some cases, shift these responsibilities from the local council to the Queensland Government. Some local government disaster managers1 have formally expressed concerns about their ability to advance strategic disaster planning when large, prioritised residential MPCs (PDA MPCs) are expanding within local jurisdictions.

In Logan City in South East Queensland, two large, state-managed residential PDA MPCs are emerging. Interviews with Logan City Council disaster managers indicated a need for better engagement with the PDA MPC planning and development decision-makers to gain improved knowledge of changing and future landscapes. Better integrating land-use planning and disaster management for building community disaster resilience is widely advocated in policy (Queensland Government 2017b, Queensland Government 2017c, Planning Institute of Australia 2016), but still faces challenges, including optimising engagement (e.g. March & Leon 2013). Such engagement implies working together, collaborative action, shared capacity and strong relationships (Australian Emergency Management Institute 2013). Models of effective engagement (some have been developed in the disaster management space) include identifying and engaging stakeholders and resources, information sharing and ongoing commitment. They offer a conceptual framework for this area of research (e.g. Australian Emergency Management Institute 2013, National Research Council of the National Academies 2011).

Aims

This was an exploratory study using Logan City as a case study. Using a concept of ‘engagement’ as the liaisons and means that immediately support information sharing, the aims of the study were to:

- capture and report expert knowledge and reflections of contemporary engagement from active participants in a development-and-disaster-management context

- understand the perceived gaps in information sharing and engagement that can hamper local, strategic disaster planning

- consider ways to facilitate better engagement based on suggestions and opinions from participants.

Stakeholder representatives who participated in this study comprised local disaster managers, emergency services representatives, land-use planners, development assessors (state and local level) and land developers. The insights offered during this study provide a basis for further research to analyse and critically evaluate specific current practices to identify improvements.

Disaster management and land-use planning frameworks

Queensland local governments assume lead responsibility for local disaster management within a hierarchical policy and management framework (Disaster Management Act 2003 (Qld), Queensland Government 2018). Land-use planning and development assessment can, however, be managed locally, or in the case of some PDAs, at the state-government level.

In general, Queensland local governments, guided by state planning legislation and subordinate policies are responsible for local land-use planning and development assessment (i.e. the Planning Act 2016 (Qld) replacing the Sustainable Planning Act 2009 (Qld), Queensland Government 2017b). Considerations of hazard risks and community resilience are achieved through addressing state interests in the local planning scheme (i.e. Queensland Government 2016).

When the Queensland Government considers developments (including MPCs) to be of economic importance, they can be declared as a PDA and removed from the regular planning and assessment system under the Queensland Economic Development Act 2012. Planning and assessment are executed by Economic Development Queensland (EDQ)—the Queensland Government’s specialist, state-level land-use planning and development unit—unless development assessment is delegated to local government. In undertaking these functions, EDQ considers state planning policies and interests (i.e. those developed under the Planning Act 2016 (Qld)). PDA declaration, however, reflects a clear government intention to expedite development. PDA planning schemes generally take precedence over other schemes and provisions to make appeals are limited.

Although PDA planning and development assessment functions have been turned over to local governments in several cases, external management by EDQ is common and, therefore, warrants attention related to its engagement with local disaster management. Large MPCs in South East Queensland that are managed by EDQ include Yarrabilba and Greater Flagstone (Logan City), Caloundra South (Sunshine Coast) and Northshore Hamilton (Brisbane). Smaller developments are located near Gladstone (Central Queensland) and Townsville (North Queensland).

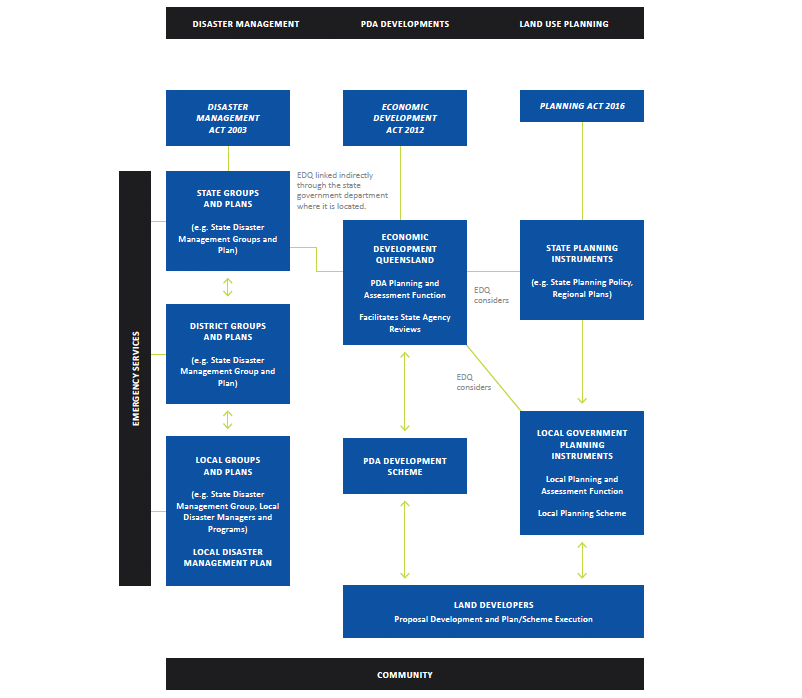

Figure 1 is a simplified illustration of the land-use planning, development and disaster-management frameworks. Indications of current ‘institutionalised’ engagement between entities is shown and reflects the present degree of separation between the existing structures.

Figure 1: Simplified representation of the contemporary frameworks for disaster management, PDA development and land-use planning in Queensland showing the strong, formalised and institutionalised linkages.

Research methods

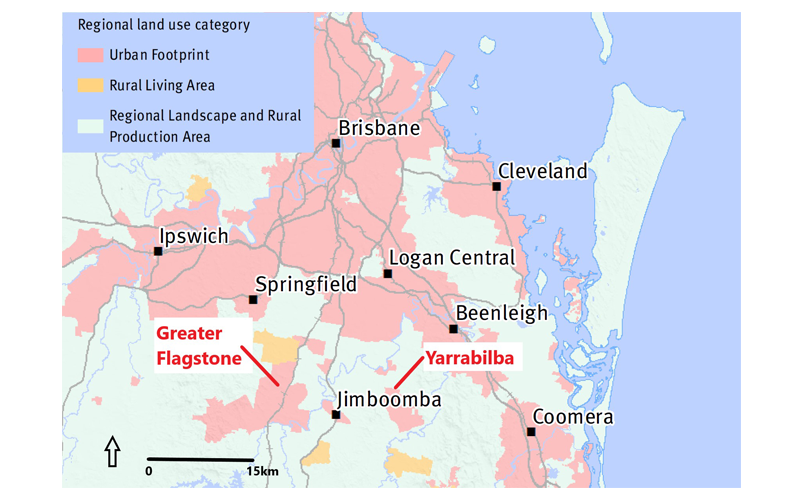

Research consisted of separate, semi-structured, face-to-face group interviews with volunteer stakeholder representatives relevant to disaster management and PDA MPC development in the Logan City area (see Table 1). Figure 2 shows the local government (council) area of Logan City and includes the PDA MPCs of Yarrabilba and Greater Flagstone, both managed by EDQ (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The Greater Flagstone and Yarrabilba priority development areas within Logan City local government area. Source: Queensland Department of Infrastructure, Local Government and Planning (2017a). The information on the maps in this source is not intended for reference to specific parcels of land and should be treated as indicative only.

Before the interviews, participants were provided with proposed discussion themes covering a range of locally relevant disaster and risk management topics. These included the nature and efficacy of stakeholder engagement regarding disaster management for PDA MPCs. Local council disaster managers were interviewed first to focus the research around a local disaster management perspective.

After each group interview, the data were interpreted and a synthesised account of discussions was forwarded to the participants for ratification.

Participants reviewed and returned them to the researchers. These final versions were manually interpreted and analysed qualitatively using a thematic content analysis to resolve narratives that specifically addressed the research aims. Analyses were conducted with reference to PDA MPC land-use planning and development and disaster management frameworks and guided by the study’s conceptual model of engagement. Ethics approval was obtained from the Office of Research, Bond University (Bond Ethics Reference Number BB00054).

The reported results and discussion are based on the ratified stakeholder interview data and its subsequent interpretation, synthesis and analysis. As flagged, engagement here particularly refers to the liaisons and means that immediately support information sharing.

Logan City PDA MPCs

Yarrabilba and Greater Flagstone are characterised by their planned size, growth and fragmentation away from existing urban areas. Yarrabilba, located south of Logan Central, is a fast-developing MPC anticipated to house approximately 50,000 people on about 2200 hectares. The site is exposed to bushfire risk and flooding is an issue for some existing residences immediately downstream of the development, making the management of stormwater run-off an important consideration. The area is periodically affected by thunderstorms. Developer Lendlease participated in the research and is progressively developing Yarrabilba, where the population now exceeds 8000.2 Greater Flagstone is similarly under development by Peet Limited. It is located to the west of Yarrabilba and has an expected population of 120,000 (Queensland State Development, Manufacturing, Infrastructure and Planning 2019).

Results: stakeholders’ knowledge and reflections

Supporting local disaster management

The initial interview with the Logan City Disaster Management Program representatives (local disaster managers) revealed there were opportunities to progress information sharing and engagement between that group and the land-use planners and development assessors responsible for the Yarrabilba and Greater Flagstone PDA MPCs; both being managed by EDQ. Timely exposure to detailed, fit-for-purpose information on evolving or planned changes such as population size, demography, community infrastructure and the design of the built environment would augment the understanding of local council disaster managers of what the growth areas would look like in coming years. This could hence underpin enhanced strategic disaster planning for the area. Improving and formalising mechanisms for information sharing between local disaster managers and PDA planning and development stakeholders, including EDQ, state agencies and developers, was viewed as a way forward.

Community education and engagement related to disasters is another role of the local Disaster Management Program that would benefit from improved information about land developments. Community needs as well as available and required facilities would be identified. Target audiences could be better defined and anticipated in designing information and education programs.

The research refined how the Disaster Management Program and stakeholders managed PDA MPC developments and ways to share information for better outcomes.

Table 1: Details of groups and participants.

| Groups | Level | Responsibilities representing | Number of interview participants |

| Logan City Disaster Management Program | Local government | Local disaster management and planning | 2 |

| Logan City Major Developments and Appeals Program and place managers | Local government | Local land-use planning, development assessment and place management | 4 |

| Lendlease | Private developer | MPC planning and development | 3 |

| Economic Development Queensland | Queensland Government | MPC PDA planning and development assessment | 4 |

| Queensland Fire and Emergency Services Emergency Management and Community Capability Unit | Queensland Government | Community resilience and risk mitigation, sustainable development | 2 |

Local government engagement with EDQ

The study indicated there was significant liaison and information sharing between Logan City council land-use planners and development assessors (and development-related council entities) and EDQ regarding developing PDA MPCs. The local council’s role was one of consultative and strategic involvement, which supported their later role in assuming community assets and responsibilities when the development project is completed. Local land-use planners and development assessors, however, had limited involvement in producing PDA MPC development schemes, infrastructure master plans and overarching site strategies. This included the application of hazard-related risk management in these plans.

The appointment of local ‘place managers’ for Yarrabilba and Greater Flagstone at the Logan City Council enhanced engagement between EDQ and Logan City Council. Their role was to provide a contact point liaison between EDQ, local planners and development assessors and other council business units. The place managers were informed by EDQ of progress in PDA planning and development and generally knew the volume, nature and status of development applications and approvals. They are valued as being a focus point to synthesise a consensus local government view from diverse or fragmented information, responsibilities, motivations and interests. The land-use planners and development assessors and developers viewed the establishment of place managers as a significant step to provide a single local contact and conduit for council-related matters. The study interviews indicated that contact between EDQ and the place managers was ‘frequent’ and included face-to-face meetings, although this was dependant on the issues and needs. There is a distinction between the place management role described in this study and that of ‘place making’. Responsibility for place making that typically involves planning, design and social infrastructure development to create community cohesion and a sense of place remained with the developer and is guided by EDQ guidelines.

Engagement between local Disaster Management Program managers, EDQ and the place managers was less structured. Disaster managers understood EDQ’s role in administering the Yarrabilba and Greater Flagstone developments but there were no direct means of engagement between the program and EDQ. Engagement with council-based place managers does not occur on a regular and systematic basis.

From an EDQ viewpoint, disaster management was largely a local government responsibility. The compatibility of a PDA with local disaster planning was not purposefully addressed in the understanding that local disaster managers develop their own plans to recognise and manage new PDAs in their local area. PDA development schemes (and related instruments) provided a holistic, ‘high order’ framework and incorporated information including population projections and densities, development footprints and development types.

Engagement within local government

The establishment of place managers and, hence, the information exchange between land-use planners, development assessors and EDQ suggested that significant detail on PDA MPC developments was potentially available through mechanisms of information sharing within local government. The study indicated that land-use planners, development assessors and place managers did not participate in the Local Disaster Management Group but could be invited to attend as advisers. This had occurred, but the PDA MPCs had not been extensively discussed in this forum. Data describing planning, development and community profiles were on local databases but participants were uncertain if stakeholders were aware of these sources and their accessibility.

Improved engagement between local land-use planners and disaster managers was generally supported, but differing perceptions of their roles in disaster risk management were obvious in the study. The role of land-use planning was viewed by planners as mitigating hazard risks ‘up front’ by applying state planning policies and interests through local zoning and development codes to assess development proposals. Disaster managers conceptualised their objectives in terms of strategic, holistic and adaptive landscape management and planning, rather than being focused on operational responses to events, as can be the perception.

Developer, emergency services and local government engagement

The Queensland Fire and Emergency Services (QFES), EDQ and Lendlease had productive, ongoing and frequent interactions regarding PDAs, including Yarrabilba. This was driven by state-level, EDQ-led processes of PDA planning and development approval. In the early stages of planning and development, EDQ facilitated the engagement across state agencies (including with emergency services organisations) and engaged with agencies on specific planning and assessment issues. Outcomes were fed back to the developer. Local councils can be included in discussions if, for example, council reserves are involved. With Yarrabilba, QFES conducted reviews of the interim and final plan schemes and guided operational and strategic considerations, including infrastructure requirements.

QFES engaged directly with developers in conversations when operational conditions were being considered (e.g. development staging). For Yarrabilba, Lendlease initially engaged with emergency services organisations through EDQ but then continued direct liaison for the provision of land for emergency services (required by EDQ) and the establishment of these services in the community. Meeting schedules were not necessarily regular nor formalised (i.e. were based on need) and occurred every few months, with EDQ ‘kept in the loop’. EDQ, still the primary planning and assessment entity, was noted to be content with handing over service-provision decisions to the appropriate agencies once land handover had occurred.

In terms of Queensland’s disaster management system, local and district QFES (and emergency services organisations generally) are typically represented on local and district disaster management groups. This facilitates their contact with local disaster management programs. QFES advocated a multi-level approach to engagement; dealing locally with the community but escalating complex legal and planning issues to higher levels within a robust, hierarchical structure. Based on their experiences, QFES considered this approach covered strategic issues, local issues and service and planning requirements as well as opened opportunities for all-hazards-based cooperative planning and management.

Developers were less likely to systematically engage with Queensland’s disaster management system through disaster committees and groups membership. However, Lendlease provided information to entities, including to the Logan City Council, as well as via the appropriate place manager. Lendlease also deals directly with specific council business units with the knowledge of the place manager as well as with emergency services organisations. The place manager indicated that Lendlease’s protocol of engaging with local disaster management programs was through that role.

Discussion: facilitating better engagement

These results and discussion are based on one case study of Logan City local government area. Application of study results to other areas and contexts is a matter for further research. However, anecdotal evidence suggests broader application in comparable development situations.

Stakeholder accounts and reflections of information sharing and engagement revealed that relationships and networks were underpinned by formal policy and legislative requirements but significantly supported by less formal arrangements and local stakeholder initiatives. Although productive engagement between EDQ, the Logan City Council, the developer and QFES were noted, gaps were identified in the information flow between the local Disaster Management Program and land-use planning and development stakeholders. These gaps resulted from a lack of formal inclusion of local disaster managers in planning and development frameworks and, conversely, lack of involvement of land-use planners, assessors and developers in those of disaster management.

The reflections and comments of the participants prompted discussion of two potential engagement mechanisms to enhance information sharing: use of the Local Disaster Management Group and the engagement of place managers. Study participants offered critical appraisals of these suggestions and made further proposals for arrangements and protocols to improve the situation.

Augmenting local disaster management groups

Disaster management groups offer an existing, institutionalised, vertically integrated pathway for stakeholder engagement that can meet the criteria for good practice (e.g. Australian Emergency Management Institute 2013, National Research Council of the National Academies 2011). Representatives from government, emergency services organisations, critical infrastructure providers and community groups are already part of these groups. However, Queensland disaster management policy and guidelines do not mandate positions for EDQ nor land developers on the state, district or local disaster management groups and committees. While it may be possible to invite EDQ and land developers as observers or advisers to these groups, it has not occurred regarding the Logan City PDA MPCs.

The proposal to have EDQ and PDA developers represented on local and district disaster management groups was canvassed with study participants. While not dismissive of the proposal, both EDQ and PDA developer participants expressed concerns about the practicality of the approach. EDQ already embraces wide-ranging responsibilities and has no direct role in operational matters in disaster management and advocates agencies should take responsibility for their strategic planning in their areas of business. Greater involvement of land developers on district and local groups risked ‘overloading’ these groups with additional and diverse membership.

Engaging council place managers

A related proposal involved the expanded use of council-located place managers in a liaison position. As local representatives for EDQ-driven PDA development processes, they can potentially engage closely and systematically with local and district disaster management groups. This could occur even when development assessment responsibilities are delegated to local government. In this case study, place managers as facilitators of engagement and information exchange were favourably supported by participants. Their inclusion in disaster management planning, particularly their involvement with the Local Disaster Management Group, could provide a conduit to PDA information for the Local Disaster Management Program. They also may promote greater knowledge across stakeholders of the needs of local disaster managers to execute their roles.

From a critical viewpoint, however, participants pointed out that place managers were not currently appointed for all major developments in all local governments. They (and their local council) would need to be amenable to expanding their responsibilities. Land developer participants indicated that place management, as described here, might not be always appropriate, including where it fosters excessive competition for resources from within hierarchical administrative structures, or contributes to the fragmentation of responsibilities. The appointment of place managers for some, suitable developments (e.g. prioritised or particularly large developments) may be a better option.

Improving arrangements and protocols

Participants were generally supportive of collaborative approaches but pathways and protocols to this end were not always clear. They were sometimes reliant on relatively informal, though often successful, processes. Participants suggested several tactics that would improve collaboration. These included:

- better defining, publicising and widely disseminating information on roles, responsibilities, chains of command and issue-specific contact points within and across relevant organisations

- improving and publicising data accessibility (e.g. development plans and assessments) so providers better understand and engage with the potential users

- encouraging and supporting wide, systematic and purposeful collaboration between local disaster management and planning and development stakeholders by promoting processes through policies, guidelines and exemplars

- investigating how the Queensland Emergency Risk Management Framework (Queensland Government n.d.) may provide a common basis for engagement and collaborative, risk-based planning.

Barriers and constraints

In this study, all participants expressed considerable desire and ‘good will’ to pursue better integration of local land-use planning, disaster management and PDA processes. However, participants observed that basic issues such as resources and staffing constraints could directly challenge local capacities to establish and maintain information sharing and engagement. The range of responsibilities often bestowed on local staff, exacerbated by high staff turnover in some areas, were two factors in this context. Also expressed was the need to address a common misconception that the role of disaster management focuses on response.

Conclusion

This research used a case study of Logan City to confirm the need to support information sharing and engagement between local council disaster managers and planners, land developers and development assessors of PDA MPCs. Study participants’ perspectives indicate a potential way forward is to establish local council place managers for major PDA MPC developments. Their role would be to liaise with stakeholders and be a single, common contact point for information exchange and referrals. Their formal inclusion in the Local Disaster Management Group would provide a clear conduit within existing frameworks for information exchange and engagement. However, the appropriateness of this approach needs to be considered in individual circumstances and supported by other improvements to information-exchange pathways and protocols.

Resolving participant reflections on engagement and information sharing and clarifying both formal and informal engagement mechanisms provides a basis on which to promote discussion and research. This research would critically evaluate engagement and its wider applicability, including in other development situations.