Whether cultural burns are the answer or not, depends on the question. During the Australian summer of 2019–20, Aboriginal peoples’ landscape fires—often called cultural, traditional or Aboriginal burns—were central in discussions about bushfire responses. Aboriginal peoples have traditionally lit ‘cool’ fires to reduce the occurrence of hot fires and for other reasons. But what question is really being asked about cultural burning?

If the question is: how does Australia eliminate large bushfires?, then cultural burns are not the answer and neither are any other bushfire risk mitigation activities. There have always been large fires in Australia and always will be.

A more helpful question is: how do we reduce bushfire risk? This approach reflects Australia’s reality. However, before discussion narrows to specific burning techniques, there are other questions, for example, what is at risk and why?

Values are fundamental to whether people do something about bushfire risk or not. This is evidenced by the difference between fire risk mitigation in western Arnhem Land (owned and managed by Aboriginal people) and neighbouring World Heritage Kakadu National Park (owned by Aboriginal people and joint-managed with the Australian Government’s Parks Australia in Canberra).

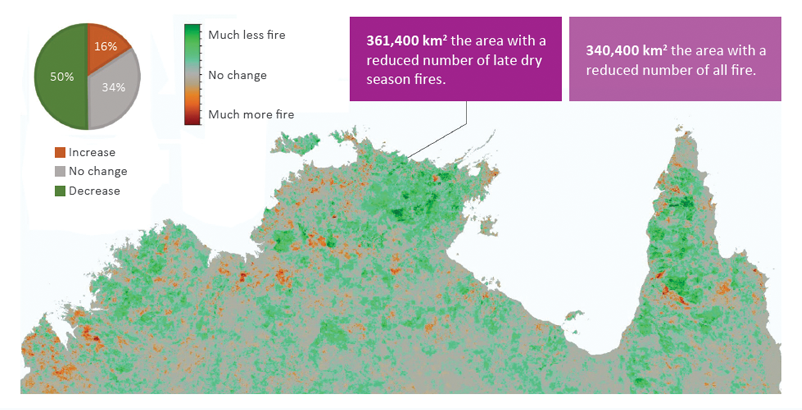

Two decades of scientific research confirms that Aboriginal burning reduced the intensity of bushfires in Arnhem Land. These results arise from Aboriginal people’s initiatives to collaborate with researchers and organisations to reduce destructive bushfires and secure international carbon abatement funding. While Kakadu has improved its fire regime marginally, satellite pictures1 show that it lags behind the success evident in Arnhem Land. The geographic proximity of the two fire regimes raises issues as to why Kakadu has not achieved similar reductions in hot fires. The answer must lie in a consideration of the human context.

Figure 1: Comparisons of the average fire frequency in North Australia between 2000–2006 and 2013–2019.

Source: North Australia Fire Information website at: www.nafi.org.au

In response to the 2019–20 summer of catastrophic bushfires, Bushfire and Natural Hazards Cooperative Research Centre CEO Richard Thornton wrote:

What is needed is a quantum shift in our thinking. Just doing the same thing or planning to do the same thing, but just more of it, is a simple solution that is neat and plausible. And wrong.

The Australian, 4 January 2020

Governments and inquiry processes looking for a quantum shift in thinking could start with Australia’s Indigenous leaders who have inherited unique knowledge that has been formed over millennia with the land. Indeed, Indigenous people repeatedly express that ‘the land and the people are one’.

Indigenous fire practitioner Victor Steffensen has said:

We can’t continue to sit back and watch hundreds of kilometres of land being annihilated and yet just sit down and just think about ourselves. But, in due respect, we need to be looking after our residents and we need to be looking after our houses, but what’s the point in doing that if we’re not looking after the land?

SBS Insight, 16 February 2016

Steffensen emphasised that looking after people and property cannot be separated from looking after the land. This does not downgrade the importance of people and property but understands that looking after the land is also looking after people and property. Indigenous peoples express this land ethic as ‘Country’.

As a researcher of meaning and assumption, I’ve studied how ways of thinking influence the possibilities that people see. I’ve tracked how explicit and implicit conceptual moves determine what is considered normal and appropriate from different viewpoints to identify where shared values lie. The environment is neither dispensable nor just a nice place to visit. People live within it and it supports everything. When we conceptually separate the land from lives, we do so at our own peril.

Cultural burns in southeast Australia made headlines for saving property at Tathra in NSW in the 2018 fire and in multiple locations during the 2019–20 bushfires. This was good news, but not the core purpose. Cultural burns are embedded in ways of knowing and doing that are attuned to the land and that sustain relationships across generations with practical and purposeful understanding. I believe the question that needs to be asked of cultural burning is: how do we understand Country? Because what is at risk is Country, and Country is everything.