The project, ‘Diversity and inclusion: building strength and capability’1 (2017–2021) has provided an evidence-based framework and new insights to support practitioners effectively manage and measure diversity and inclusion.

The report’s project was commissioned by the Bushfire and Natural Hazards Cooperative research Centre (BNHCRC) and was carried out in 3 phases: (1) understanding the context, (2) framework development and (3) testing. Each phase was subject to annual review and the program adjusted in response to those reviews.

The project used a working-from-the-inside-out methodology, a trans-disciplinary approach used to develop workable solutions to seemingly intractable problems through collaborative research codesigned with end users. It starts with understanding user needs and context, surveys available knowledge from a wide range of sources and puts this knowledge into formats that can be used in practice, which are tested and refined with end users. The purpose is so that research is fit-for-purpose and useable.

Following the scoping phase, 3 lines of inquiry were established being organisational, economic and community-based. A mixed-methods approach incorporated case studies, semi-structured interviews, focus groups, decision-making assessments, desktop reviews of organisational documents, informal and formal literature and ongoing review and feedback. The review showed that the research literature had matured and the emphasis on diversity and inclusion has moved on from addressing diversity to understanding roles of inclusion. However, few examples of successful implementation were identified. Emergency management organisations (EMOs) were poorly represented, despite global acknowledgment of low workforce diversity.

‘Diversity is what creates the change, inclusion is how you manage it’

Three case studies were undertaken that highlighted that implementation was a process of social change and the need to focus on inclusion. Diversity and inclusion principles and programs were present but were not well-integrated into systems and processes nor connected to day-to-day decision-making and tasks. It was also primarily seen as being about men and women. The largest barrier was culture and the largest need was management. A lack of strategic vision and supportive organisational frameworks and processes were resulting in mostly shorter-term, reactive approaches to achieving diversity and inclusion.

A turning point for the project occurred as part of a workshop held in December 2018 titled, Into the future: building skills and capabilities for a diverse and inclusive workforce. Analysis of the workshop outputs showed a wide range of social, human and innovation risks that were not being formally managed or, in some cases, even recognised. If left unmanaged, these risks would likely ‘impair the ability of EMOs to perform their functions effectively’.2 The connection to risk provided the connection between day-to-day tasks and the business imperative that emergency services organisations face.

Two economic case studies highlighted the benefits that could be achieved by successful programs. The Indigenous Fire and Rescue Employment Strategy program produced $20 worth of benefits for every dollar invested.3 However, existing economic models need development before programs for different cultural cohorts can be comprehensively assessed. Appropriate data also needs to be collected from the beginning of programs to support this.

The community case studies illustrated some of the complexities in relation to the capabilities of diverse cohorts and young people, but each has its own context that needs further exploration.4,5 Although culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) communities have many capabilities, there was little awareness of these, and they were often not harnessed effectively.

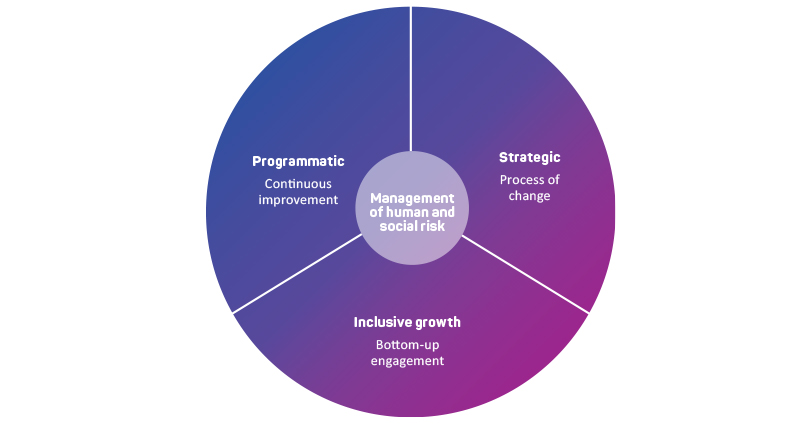

The final diversity and inclusion framework6 is constructed around 4 components as shown in Figure 1:

- Strategic – transformational change

- Programmatic – continuous improvement

- Inclusive growth – bottom-up engagement

- Risk management – human, social and innovation risk associated with diversity and inclusion.

Figure 1: Diversity and inclusion framework components.

Source: Young and Jones (2020)

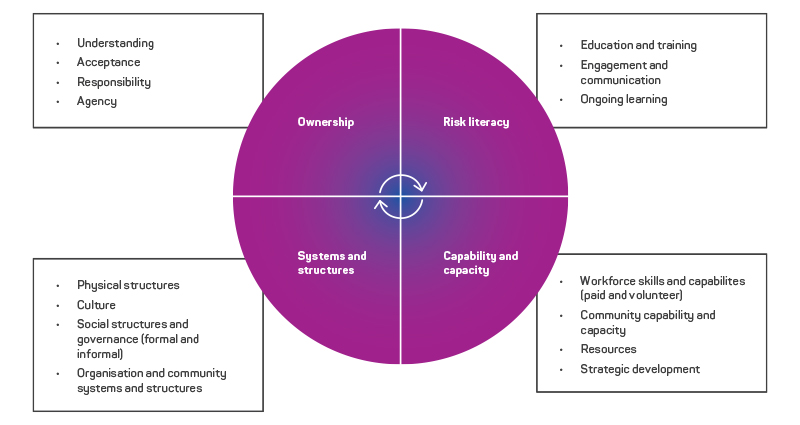

This is developed to be flexible and adaptable to aid decision-making in a range of different contexts. The strategic and programmatic processes are supported by guidance and question-focused considerations for practitioners.6 It also provides implementation areas and key tasks needed across operational areas (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Activities that support embedding diversity and inclusion risk into existing systems

Source: Young and Jones (2020)

The ‘Learning as you go’ support report7 provides case studies, guidance and tools for practitioners that includes a maturity matrix to support implementation. There are also 2 practitioner manuals that offer guidance for working with CALD communities and young people.8,9

The study has culminated in conclusive statements:

- Effective diversity and inclusion is an imperative for all emergency services organisations if they are to mitigate and manage the human, social and innovation risk associated with the changing risk landscape occupied by organisations and communities.

- Inclusive practice provides a tangible way to build robust and resilient social infrastructure in communities and organisations.

- Social and human risks associated with diversity and inclusion have been regarded as secondary to technical and tangible risks and their value is not well recognised nor understood.

- Diversity and inclusion is not a fixed-point destination to arrive at. It is a series of transitions that organisations and communities move through as they work towards a desired, inclusive vision connected to a set of agreed outcomes that may change over time.

- Inclusion is not about being permissive. It is about understanding the formation of new boundaries and who should decide what those boundaries are. This is not one conversation, but many different voices coming together to negotiate a collaborative outcome.

- Statements of inclusion drafted by diverse groups that outline the terms of their inclusion are needed to enable negotiation from a position of empowerment. These statements support the development of respectful relationships that celebrate difference through shared understandings.

- Considerable work is still needed to develop measurement protocols, particularly those related to economic evaluation and the effectiveness of inclusion.

- Further work is needed to identify and document the specific capabilities and skills in communities. Ongoing evaluation is needed to capture benefits, lessons identified and ensure that visibility is maintained.

- Social and human risk are often poorly understood and there is a need to build risk literacy in these areas across organisations.

Common aspects found to support effective programs:

- Safe spaces where difference is welcomed and accepted, where the terms of inclusion can be negotiated and concerns can be addressed.

- Organisations have an authorising environment (structures, governance and processes) and a mandate to operate (social licence) if programs are to be effective. Upper-level advocacy, support and commitment to diversity and inclusion over the longer term is critical.

- People who are undertaking and leading activities have the appropriate skills and knowledge to manage proactively and effectively. Authentic actions are critical to building trust.

- A pragmatic approach is adopted where organisational champions and leaders are able to respond, capitalise on and leverage opportunities as they arise.

- Looking beyond the organisation and understanding where the interactions between the community, emergency services organisations and other institutions (such as government), are managed and who needs to manage them.

- Developing collaborative and individual narratives that take discussion ‘beyond the numbers and quotas’ to tell stories that connect people and humanise risk so that it is understood and valued.

The high level of uptake and use of research during this 3-year project was aided by the emergency sector’s focus on progressing diversity and inclusion and the work of peak bodies and end user organisations to develop programs and leadership. It has contributed to the repositioning of diversity and inclusion as a risk-based business imperative. Its effectiveness and impact are due to the collaboration and commitment of the end user groups that have actively participated, supported and promoted the work over the life of the project.

The collateral from this project was developed in collaboration with emergency management practitioners and captures and consolidates the considerable knowledge that already exists. This project showed the dynamic nature of implementation and how different organisations are treading the long road to inclusion. Each year has produced new insights and some organisations are leaning into the uncertainty. Some find it harder, however, all of them are learning as they go.