Women are on the front line as carers in our society with 75% of the health and social care services being provided by women globally.1 They are often lower paid, experience harsher working conditions and suffer from health issues due to their work. They also represent the largest most diverse demographic that is negatively affected when disasters strike, including the COVID-19 pandemic.

Recent climate and health disasters are excellent examples of how people in Australia and New Zealand have pulled together in the face of adversity and trauma. It is a part of our social culture to look after mates and extend a hand to those who are less fortunate or in need of assistance. It is also countercultural to speak up and vocalise about positive contributions that should be acknowledged and supported equally.

In Australia, the Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety exposed major operational gaps which contributed to the loss of life for those in care.2 The health and wellbeing of the staff providing the care was also undervalued, underpaid and neglected. But we didn’t need a royal commission to tell us this. Women over 50 are likely informal caregivers, whether they are employed elsewhere or not. In doing this, it is no surprise that women over 55 are the fastest growing group to experience homelessness. At the very least, this is the loss of a most valued, irreplaceable resource.

Low-paid childcare workers, predominantly women, are on the front line as undervalued essential service providers, caring for children of other essential services workers such as health care providers. This was highlighted throughout the pandemic restrictions and lockdowns, long before there was a vaccine.

In July 2020, the childcare sector was the first to be targeted by being ‘weaned’ off JobKeeper payments by the Australian Government. The government decided that childcare workers, who were mostly women, were no longer eligible to receive JobKeeper payments due to number-crunching rationalisation in subsidies that supposedly looked after their employment and commitment to service. For many, that eventually meant the end of their employment with the closure of childcare centres that were unable to function or meet the requirements of legislated ratios.

Community-based not-for-profit childcare providers suffered the most as their other fundraising activities were ceased as part of the response to the pandemic. Today, there is a shortage of childcare educators, either unwilling to return to the demanding low-paid work or not being vaccinated. This affects other working women who need childcare, and the waiting lists are growing.

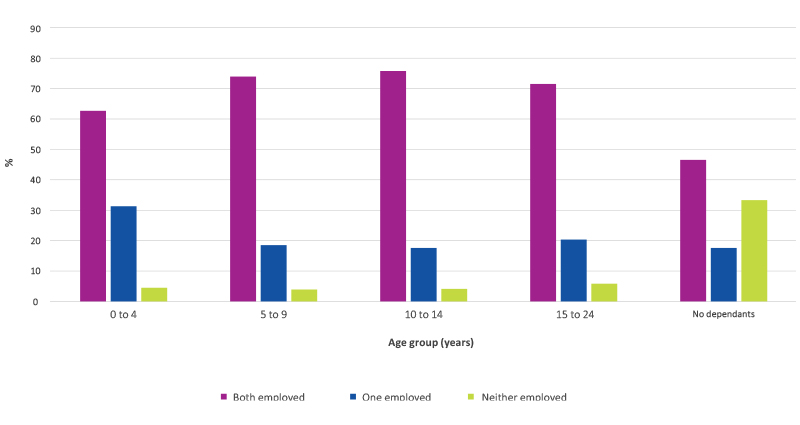

Table 1 shows that today, up to 25% of working couple families have children under 4 years old. Over 70% of couples with children under 15 have mothers who are employed. And up to 80% of one parent families are headed up by mothers.3

Figure 1: Couple families by number employed and age of youngest dependant as at June 2021

Image: Australian Bureau of Statistics, Labour Force Status of Families, June 2021

How do these statistics impact on women who were working from home during the school closures? Ad hoc reports from the community sector indicate that women were not only trying to continue with their usual home duties pre-pandemic, they were also in charge of conducting the home schooling of their children, sometimes with multiple children, while trying to keep up with their working-from-home obligations at the same time.

In many cases, partners were reported as not necessarily contributing equally to this effort. Traditionally considered as ‘women’s work’, the roles of women were regarded as having less economic benefit and could be sacrificed in some manner. But what was also sacrificed was the mental health of women to some extent. Women expressed feeling guilty about failing to meet all of their work obligations, home schooling demands, supporting their partner and keeping the home together.

When women, who perform the majority of care work, are negatively affected mentally and physically by disasters and health events, who will be available to provide the necessary care required to recover from these calamities? Society, employers and government leaders must value the work and health of women if cultures are to advance with the necessary skills and workforce required to meet the challenges of climate extremes and pandemics. We have been given a taster with the concurrent knockout punches of bushfires, floods, droughts and a pandemic over the last 2 years. If not now, then when?