Every year, flash floods hit many cities in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (Saudi Arabia) leading to many injuries and deaths as well as a huge amount of damage to infrastructure. Risks of frequent flash floods have been linked to a lack of emergency planning. This paper presents a systematic review of emergency planning for flash floods response currently in place in Saudi Arabia. Collected information was analysed based on the suitability of content and data for emergency planning in flash floods response. Aspects of the dominant approach of emergency planning and the community-based approach are examined and considered against applications in Saudi Arabia. A case study is used about flash floods in Jeddah in 2009 and 2011 to consider these approaches. This may be the first systematic review of emergency planning for flash floods response in Saudi Arabia and shortcomings listed may lead to improvements in policy, planning and training, particularly given the scientific consensus of an increase in the frequency and magnitude of flash floods in Saudi Arabia.

Introduction

The Emergency Events Database (UNDRR 2020) shows that a total of 7,348 natural disasters have occurred in the past 2 decades. Table 1 shows that between 2000 and 2019 around 1.23 million people died due to a natural hazard disaster, averaging 60,000 deaths annually, with other impacts on more than 4 billion people. In economic terms, such disasters globally caused a loss of around US$2.97 trillion (UNDRR 2020). Compared to the preceding 2 decades, the number and effects of natural hazards disasters have significantly increased. Between 1980 and 1999 there were 4,212 reported disasters across the globe, with loss of life of around 1.19 million people and impacts on more than 3 billion individuals, plus US$1.63 trillion lost in economic terms (UNDRR 2020). Remarkably, between 2000 and 2019, flash flooding made up 44% of recorded disasters and affected 1.6 billion people globally, which was more than for any other kind of disaster and averages 163 occurrences each year (UNDRR 2020).

Table 1: Effects of disasters: 1980–99 compared to 2000–19.

| Category | 1980-99 | 2000-19 |

| Reported disasters | 4,212 | 7,348 |

| Total costs from deaths | US$1.19 million | US$1.23 million |

|

Total costs from people affected |

US$3.25 billion | US$4.03 billion |

| Economic losses | US$1.63 trillion | US$2.97 trillion |

Source: UNDRR (2020)

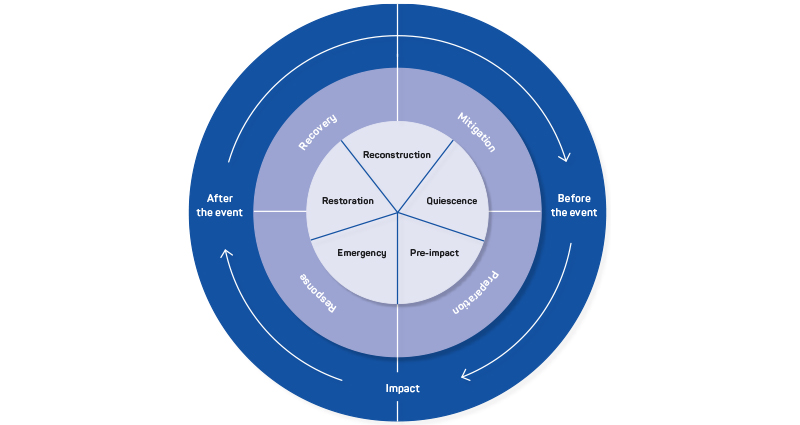

Studies including those of Alexander (2002), Shaluf (2008), Kusumasari, Alam and Siddiqui (2010) and Mikulsen and Diduck (2016), describe a 4-phase approach to managing emergencies namely: mitigation, preparedness, response and recovery, as shown in Figure 1. Each of these emergency management phases has a role in safeguarding lives as well as property. Although there is significance to actions taken in all of these phases, preparedness activities that include emergency planning are considered the most significant. The literature on managing emergencies continues to develop and the central role of planning for effective preparedness and response activities has increased in this field. With this in mind, this paper presents a systematic review of the approaches to emergency planning with a case study for flash floods response planning in the Saudi Arabia.

Motivations

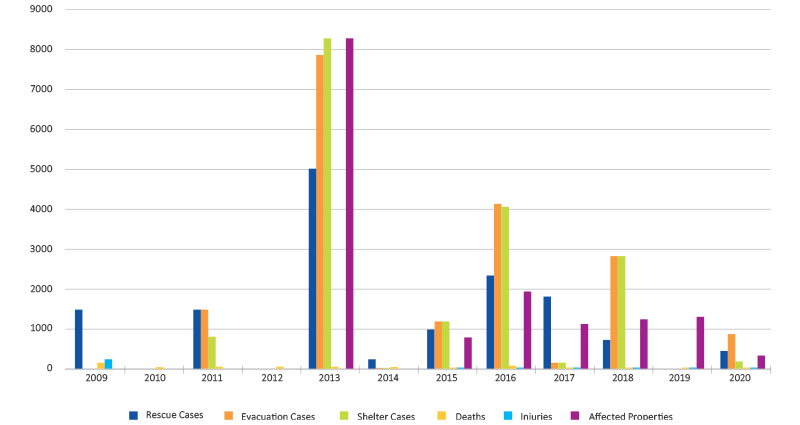

Although the climate in Saudi Arabia is characterised as dry overall, flash floods are increasingly occurring and affecting most Saudi cities (Mohamed 2017; Chen, Yeh & Chen 2018). These flash floods have resulted in injuries and deaths as well as general damage to residences, vehicles and other property (Youssef et al. 2016, Abdalla 2018) as shown in Figure 2. Both socially and economically, such events severely affect the country.

The planning for flash floods response varies significantly from country to country. In Saudi Arabia, the General Directorate of Civil Defence (GDCD) holds overall responsibility for managing and planning for emergencies as well as for protecting lives and properties (GDCD 2020a, GDCD 2020b). This is characterised as ‘working from the top down’. However, while GDCD has shown intent for identifying flash floods risks, its policies, legislation and regulation development related to emergency planning for flash floods response has been a prolonged process (Abosuliman, Kumar & Alam 2013). According to Alamri (2010), the GDCD has struggled to be proactive when planning for risks related to flash floods and may be less prepared for possible future flash floods as risk-reduction approaches are mainly reactive rather than proactive (Ledraa & Al-Ghamdi 2020).

Figure 1: The emergency management cycle

Source: Alexander (2002)

Saudi Arabia has been subject to criticism from individuals and local and international societies related to its policies, procedures and plans used in planning for flash floods. It is clear that there is a need for effective emergency and disaster response planning on the part of the decision-makers and response agencies. This systematic review of the literature aims to understand the trends in planning for emergency and disaster response that focuses on flash floods response in Saudi Arabia. Lessons are identified.

Methodology

Research approach

According to Khan and co-authors (2001), a systematic review is defined as:

A review of the literature on a clearly formulated question that uses systematic and explicit methods to identify, select and critically appraise relevant secondary data, and to extract and analyse data from the studies that are included in the review. (p.12).

The literature review for this paper was performed on databases such as Google Scholar and Scopus, since each database has different functionality. The research used terms such as: 'disaster response', 'disaster preparedness', 'emergency planning', 'emergency management policies and plans', 'emergency training or capability' and 'flash floods in Saudi Arabia. The full papers (in English or Arabic languages) were used on yearly national emergency prevention and response, on flash floods, threats and mitigation of floods, emergency preparedness, emergency response, flood guidance and emergency policies/decrees. The papers were evaluated on the basis of their link with disasters and components of disaster management, especially preparedness and planning for response to flash flooding.

English and Arabic publications were selected that related to disaster preparedness and response planning research in Saudi Arabia between January 2000 and December 2020. Publications that included compound terms such as ‘emergency policy and preparedness’, ‘disaster management reforms’ or ‘floods impacts’ were analysed, regardless of the paper's form and content.

The full publication type for each paper was analysed on disaster preparedness and response planning. Any overlaps were noted, such as between preparedness and response policy and disaster management. In order to explore how prepared Saudi Arabia’s government and response authorities are with regards to responding to flash flooding, emergency planning papers linked specifically to flash floods were reviewed, except those that did not match the full criteria.

An Excel spreadsheet was used to compile the data and to analyse themes of emergency planning for flash flood response and any challenges, particularly in relation to flash flooding in Saudi Arabia.

Figure 2: Frequency of flash floods in Saudi Arabia between 2009 and 2020.

Source: GDCD (2021)

Results

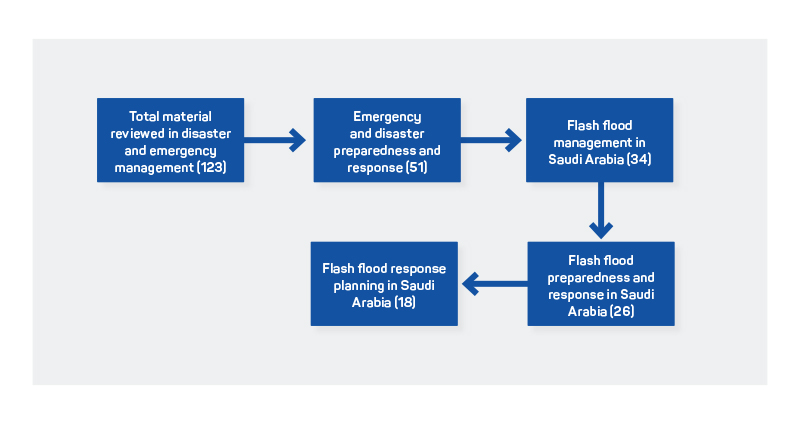

A total of 123 articles, papers and plans were obtained and reviewed. Of these, 18 complete papers met the inclusion criteria, including the GDCD website. These were analysed based on the suitability of content and data for emergency planning for flash flood response in Saudi Arabia (see Figure 3).

Discussion

Planning

Governments, experts and organisations are continually working on methods to prepare for and respond to hazards and threats to minimise the severe effects of these events on individuals, communities and infrastructure. Planning is an essential and vital part of the preparedness phase. The concept of planning varies according to the field in which it functions. Generally, scholars have held that it has been taking place since biblical times: the story of Noah’s Ark is often cited as one instance where plans were developed in advance of a severe disaster. Additionally, Alexander (2002) states that emergency planning started to spread in government, business and culture in the 1990s and defines emergency planning as, ‘A response to the requirement to enhance safety as well as progressing understanding of hazards’ (p.10).

The wide range of disasters that has led to extensive harm and lives lost attests to the importance and value of planning. Zhao and co-authors (2017) indicate that before an event occurs, emergency planning can effectively minimise the harm; in other words, emergency planning is key for effective emergency management. The approaches to emergency planning include how planning should be performed and who should be doing it. In general, 2 viewpoints have been established over the last 2 decades: the ‘dominant’ and the ‘community-based’ approach.

The dominant approach

Looking into history, planning was a unidirectional, information-driven process implemented ‘top-down’ by practising specialists of emergency planning (McGuirk 2001). This approach is known as the dominant approach and concentrates on hazards as the main factor in an emergency and positions it as central to response planning. Based on this interpretation, the dominant approach tends to concentrate on strategies for infrastructure such as flood dams and technological solutions to control the hazard. A dominant ‘top-down’ strategy may also recommend, for example, moving individuals to safer areas to avoid the flood threat.

The historical record of the dominant approach can be seen, for example, in the use of constructed flood controls such as dams in ancient urban civilisations (Jones 2000, Fleming et al. 2001). Additionally, the Indian Ocean tsunami in 2004, was monitored by a highly technical early warning system. The severity of that event resulted in a request from the British government for a Natural Hazard Working Group meeting to be held to advise on the monitoring of tsunamis, floods, cyclones and other natural disasters (King et al. 2005).

The dominant approach, however, is marked by many flaws. Several studies have criticised the organisational top down approach in emergency planning, especially in the developing world (Jain 2000, Magrabi 2012). These difficulties and shortcomings prompted planners to investigate other decision-making methods and to encourage community participation. A gradual transition from the dominant approach to the community-based approach is ongoing albeit slower than expected (Buckle, Marsh & Smail 2003).

Figure 3: Literature review search results for emergency planning for disaster response.

The community-based approach

The community-based approach includes planning that is undertaken by a variety of people and typically values democratic and opinion values. There is a dependency on engagement and consultation and also on the representation and interaction of a variety of participants. The community-based approach emphasises inclusion and participation of partners in the planning stage as well as the cooperation and coordination between decision-makers and affected communities (Innes 2004, Koontz & Johnson 2004). The concept is also known as ‘community-based’ in non-government organisations and community-based organisations.

Giddens (2013) indicates that the theoretical framework for the community-based approach is based in Critical Theory by Jürgen Habermas. In the decision-making phase, planning includes and involves all stakeholders and planners to facilitate shared comprehension of the information based on real, truthful communication and discussion between planners and community members. In this way, the community-based planning approach is intrinsically collaborative, consultative and participative.

The main difference between this approach and the dominant approach is that it stresses susceptibility to a hazard instead of the hazard itself, with groups considered vulnerable being able to participate effectively as part of the problem-solving efforts. The community-based approach provides a ‘bottom-up’ procedure from the people at risk, showing the connection between disasters and humans and their physical, economic and social situations. Thus, Heijmans (2004) argues that successful emergency planning should be based on social, political and economic community factors.

Although the community-based approach is widely acknowledged by many community organisations, others underestimate the role of local communities. In India, the High Committee on Disaster Management argued that due to the low literacy levels and extensive poverty of their population, the community as an important entity is yet to take form (National Centre for Disaster Management 2001). However, there have been many attempts to shape and enhance local community-based organisations.

Jeddah flash floods: a case study

The statistical analysis of disasters showed that the most widespread threat in the past 2 decades has been flash floods (Alamri 2010, Youssef et al. 2016). This risk is largely due to the geography and topography of Saudi Arabia (Solecki, Leichenko & O’Brien 2011). To explore the effectiveness of emergency planning in Saudi Arabia, the Jeddah flash floods in 2009 and 2011 are examined as a case study. Figure 4 shows the location of Jeddah city.

Figure 4: Location of Jeddah City within Saudi Arabia.

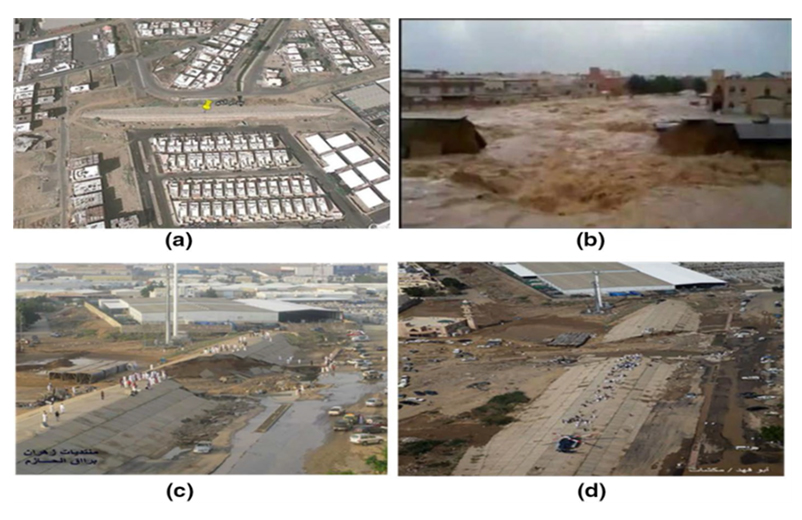

On 25 November 2009, the city of Jeddah experienced substantial rainfall with 90mm of rain within 4 hours. This was twice the city's annual average (Azzam & Ali 2019). Flash flooding hit multiple areas across Jeddah at midday and poorer neighbourhoods to the south of the city were most affected (Abosuliman, Kumar & ALam 2014). Less than 2 years on, on 26 January 2011, the city suffered another severe heavy rain event of 111mm (Ameur 2016). Azeez and co-authors (2020) state that this heavy rain led to a flash flood, causing the Um al-Khair Dam to fail. As a result, many people, homes and other properties were destroyed or severely damaged. Figure 5 shows a collection of satellite images of the Um al-Khair Dam. Image (a) is the dam before the collapse, image (b) shows the dam during the failure, image (c) shows the second day of the flash flood and image (d) shows the dam several days after the flash flood.

The damage from both flood events was vast: 161 people lost their lives in the first occurrence and a further 11 died in 2011 (Ameur 2016, Youssef et al. 2016, Azzam & Ali 2019). Furthermore, 8,000 homes and over 7,000 vehicles were damaged (Abosuliman, Kumar & Alam 2014). The economic damages totalled approximately US$1 billion and the reimbursement for those affected was projected at a further US$2 billion (Ameur 2016). The floodwaters washed across 80% of the city, including highways, sidewalks and structures and covered around 400 to 600km2 (Azzam & Ali 2019). The flash flood effects led to condemnation by numerous accountable Saudi government organisations including wastewater control, flood prevention and emergency response (Al-Saud 2010).

Figure 5: Satellite images of the Um al-Khair Dam before (a), during (b) and after the collapse (c) and (d).

Source: Azeez et al. 2020

The primary objective of investigations into the Jeddah flash floods was to determine how response was planned. Firstly, there was a lack of data for forecasting, mitigation and emergency planning. The advanced warning system was ineffective and an incomplete Emergency Relief Plan also contributed to planning failures. A further and fundamental reason for inefficiency was the strictly centralised aspect of the emergency management system. Even though response and relief activities have been evident in rebuilding and rehabilitation and there has been a greater focus on the response and recovery phases, it does not mean that such phases were successfully applied. In fact, difficulties were likely to arise in each of the phases. Additionally, the lack of a master flood management plan was an important reason for a poor response. Finally, there were no qualified teams or special emergency response training at either the city or national levels.

This case summary indicates that the contributing failures could include:

- inefficiency in advanced emergency planning

- a top-down, centralised system for emergency planning rather than a bottom-up approach

- stakeholders are not involved in disaster response planning

- poor contact, collaboration and cooperation between response organisations, local communities and stakeholders

- inefficient or non-existent training in responding to floods

- a lack of preparation, experience and knowledge about major risk areas

- no central database system or a way to monitor and control the information management system.

Conclusions

This paper presented a systematic review of emergency planning for flash floods response in Saudi Arabia. This included a discussion of the dominant and the community-based approaches to emergency planning. The recognised advantages in using a community-based approach for emergency planning still experiences limitations on what could be accomplished through identification and analysis of risks as well as potential solutions at the community level. For example, when identifying and analysing potential hazards, communities may not place adequate focus on hazards and risk they have not yet encountered. These could include dormant volcanoes or threats associated with a changing climate.

Conversely, the remedial steps required using the dominant approach could be hampered by the substantial economic costs required to implement such steps. For example, flood risks found in upstream communities would affect downstream communities and they should also be considered. The resources needed to address these factors could generate further risks. Thus, it might be that a mixture of dominant and community-based approaches is an effective method for emergency planning for flash floods response.

There are challenges facing current emergency planning for flash floods response in Saudi Arabia particularly related to a lack of policies, an ambiguity of legislation and plans, poor coordination between stakeholders, a lack of involvement from all stakeholders, a lack of databases for emergency planning and poor training for personnel. Encouragingly, compared to neighbouring countries, emergency planning in Saudi Arabia has greatly improved over the past 2 decades. However, the focus remains on handling disasters reactively, rather than on planning for possible future hazards and being proactive and taking a risk-reduction approach. Emergency planning requires a proactive attitude and a mixture of the dominant and community-based planning approaches, especially with regards to flash flood preparedness, early warning systems, response planning and hazard risk identification and treatment.