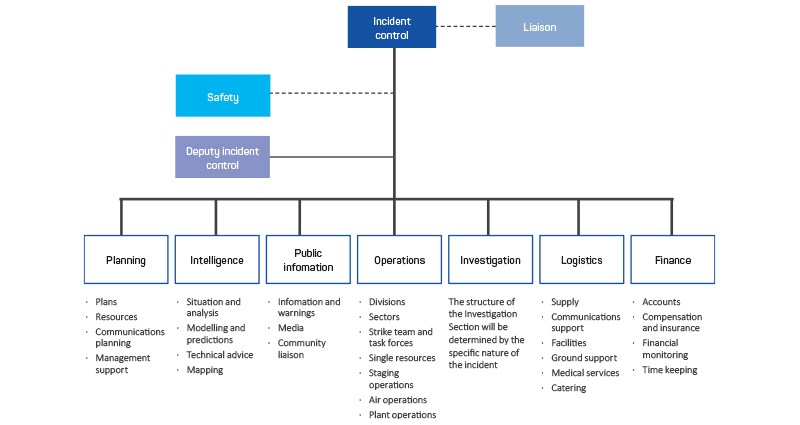

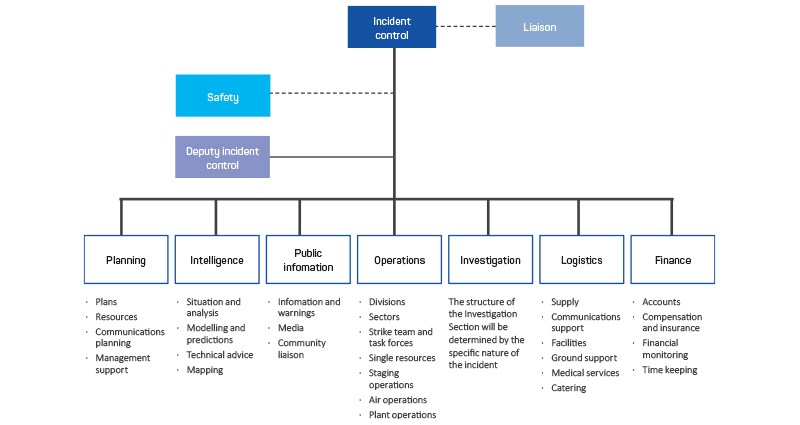

In AIIMS, every incident has these functions. In a very small fire (e.g. a park bin set a light) all the functions would be performed by the crew commander of a single fire appliance who would be the incident controller and the entire IMT. At a state-level, the IMT would scale up so that each of the functions would be headed by a senior officer supported by a staff (see Figure 1).

AIIMS is a robust system for incident management. IMTs exist until the incident that caused it to be stood up is resolved. In services with large numbers of volunteers (e.g. the NSW Rural Fire Service (NSWRFS) or the NSW State Emergency Service) the volunteer crews are stood down as soon as possible so that volunteers may resume their normal lives. The salaried work forces of these agencies are quite small and exist to support the volunteer workforce. Among the NSW combat agencies, it is the NSW Police Force that have an entirely full-time, salaried workforce; even Fire and Rescue NSW (FRNSW) has some part-time salaried firefighters.

PPRR

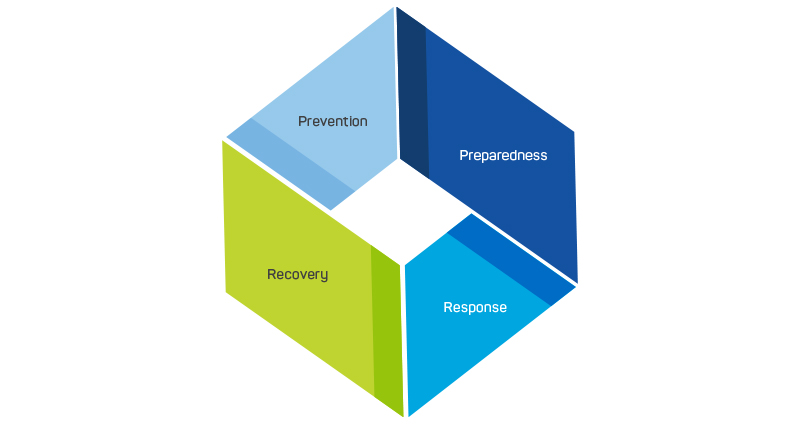

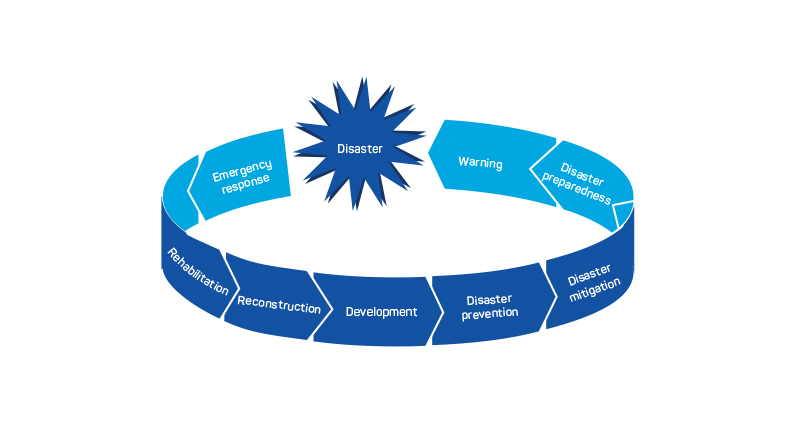

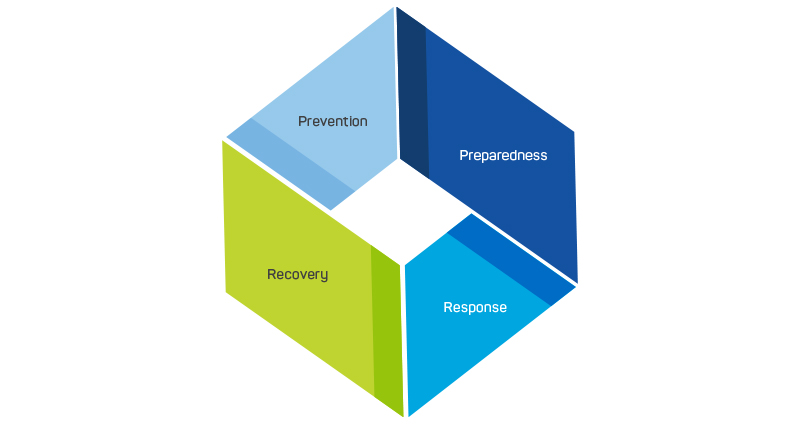

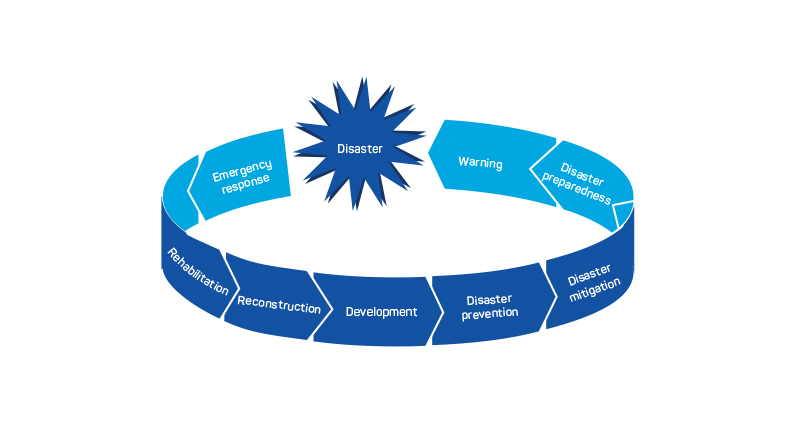

The PPRR cycle is commonly used in emergency management. Often, ‘mitigation’ is substituted for ‘prevention’ (Petak 1985, p.3; Simonović 2011, p.31). The model has its origins in the USA from 1978 (Crondstedt 2002, p.10, Rogers 2011, p.55). The model is used in the NSW State Emergency and Rescue Management Act 1989 to describe the ‘stages of an emergency’ (State Emergency and Recovery Management Act 1989 (NSW), s. 5). Figure 2 shows the 4 interconnected phases of the PPRR model.

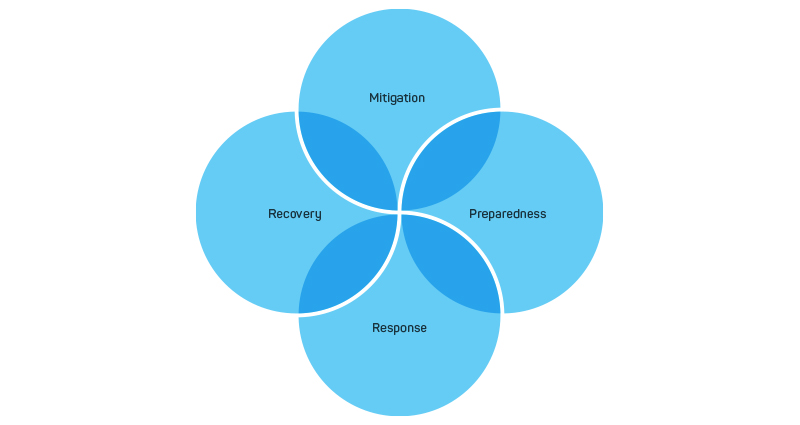

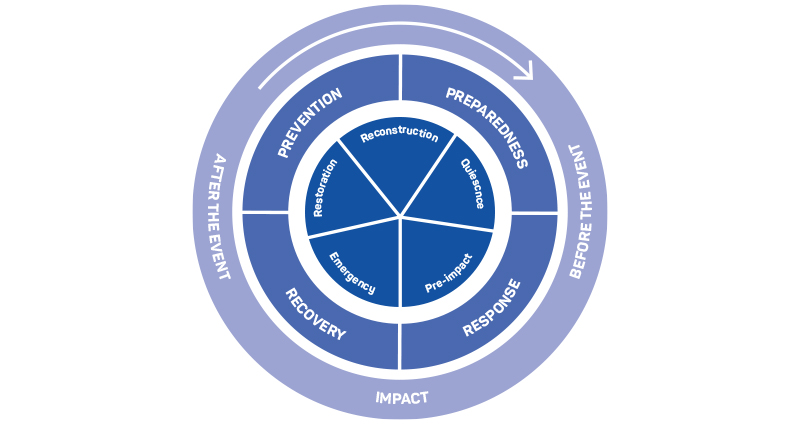

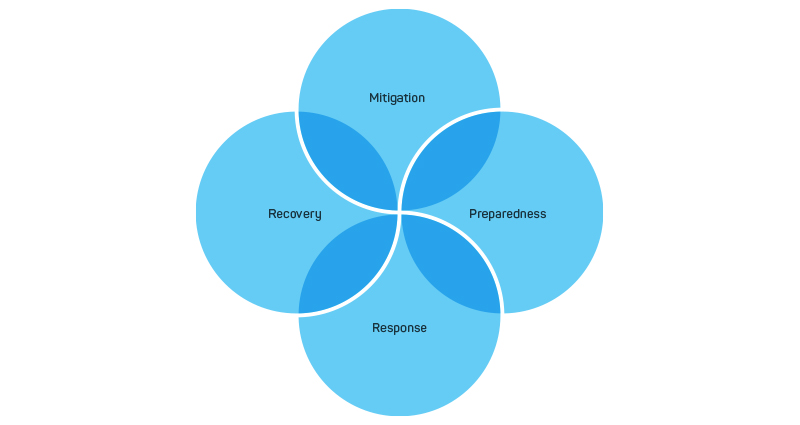

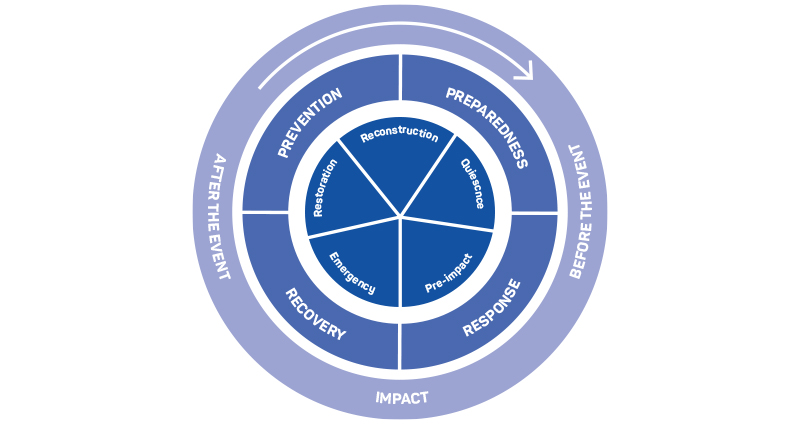

Simonović (2011), advocating an integrated approach to emergency management, presented PPRR in a Venn diagram (Figure 3). The overlapping sectors suggests there is a central coordination function. Coppola (2015) provided a more complex construct to show the inter-relationships between stages of an emergency. In Figure 4, the emphasis is that disasters tend to exist in a continuum, with the recovery from one often leading straight into another. And while response is often pictured as beginning immediately after an event, it is not uncommon for the actual response to begin before the event actually happens (Coppola 2015). In this model, all phases can coexist within a dominant phase.

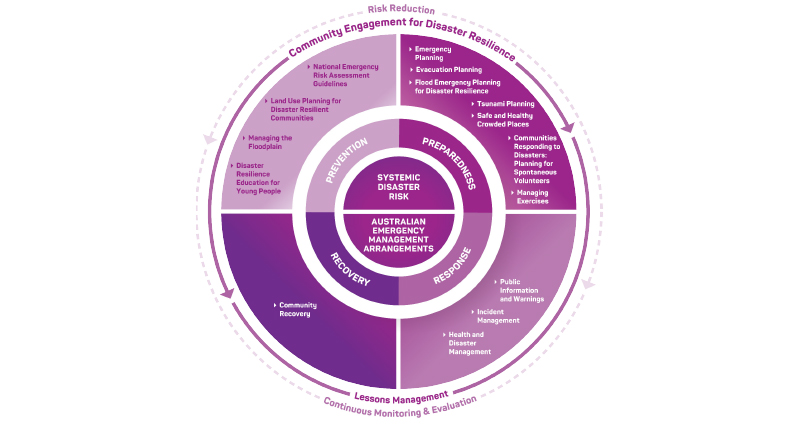

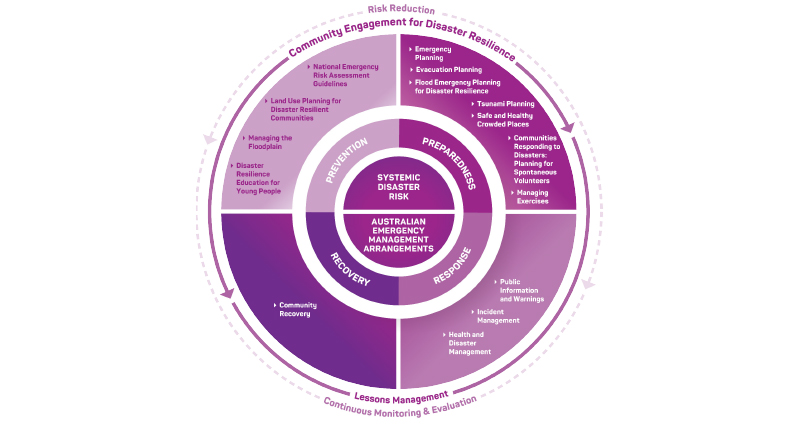

Figure 5 shows a detailed version of the PPRR model from the Systemic Disaster Risk Handbook (AIDR 2021) in its description of its ‘landscape’. The value of the model lies in its detailed allocation of emergency management activities and documentation for each phase. The lack of activities in recovery is notable, reflecting the relative lack of attention paid to recovery.

There are variations on the 2-dimensional cyclic representations of PPRR. Kelly (1999) noted Neal’s (1997) criticism of the essentially linear sequence in the conventional PPRR model where different sections of a population can experience different parts of the cycle simultaneously. This can be represented by Coppola’s (2015) Venn diagram model. Figure 6 shows a Mobius strip model, proposed by Anderson (1985), Cuny (1985) and (Kelly 1999, p.25). While it may be debatable whether this model amounts to a substantial change, Kelly (1999) offers a different visualisation of what occurs before, during and after an incident.

Figure 1: A fully expanded incident management structure showing functional areas.

Source: AFAC (2017), p.46.

Figure 2: The emergency management cycle.

Figure 3: The emergency management cycles as a Venn diagram of interrelated phases.

Source: Simonović (2011), p.31.

Figure 4: The emergency management model as a continuum.

Source: Coppola (2015), p.13)

Figure 5: The emergency management cycle is represented as a ‘policy landscape’.

Source: AIDR (2021)

Figure 7 shows the quadrants on a plane that are expressed in terms of resource use (Kelly 1999, p.26). The value of this model is that it does not envisage a situation where no resources are needed: what changes are the proportions.

A variation on the PPRR model comes from the NSW RFS in Figure 8. The value of this representation is the suggestion of a wave flow of events within a linear model. This reflects the perception of firefighters oriented to response while acknowledging the broader PPRR range of activities.

The PPRR model is not without its critics. Rogers (2011) expressed concern that the conventional PPRR cycle does not include ‘anticipation and assessment’ of risk sufficiently in the cycle to properly inform national resilience (Rogers 2011, p.54). Cronstedt (2002) argued that the model is agency-focused rather than community-focused (Crondstedt 2002, p 11). Gabriel (2003) criticised the model because it is solely emergency-focused. Gabriel (2003) writes that it is inappropriate to concentrate on response and the necessary recovery when the emphasis ought to be on the community through treatment or risk reduction. Linton (2021, pp.5–6), while agreeing with Gabriel’s (2003) criticism, claimed that the PPRR model has a value and should be allowed to evolve to focus on disaster risk reduction. With PPRR enshrined in NSW emergency management legislation, the framework continues to define how government agencies plan for and manage emergencies.

Figure 6: The emergency management cycle shown as a circular Mobis strip.

Source: Kelly (1999), p.26

Figure 7: The emergency management process phase shown in terms of resource use.

Source: Kelly (1999), p.26

Figure 8: The emergency management cycle shown as a wave of events occurring along a linear phase of an event.

Source: NSW RFS (2019)

AIIMS, PPRR and agencies in NSW

AIIMS and PPRR differ fundamentally. AIIMS has been adopted and used operationally in emergencies across Australia and New Zealand for 20 years. PPRR is a theoretical framework used to explain the work of emergency management. Unlike AIIMS, which requires agencies to comply with its practices, PPRR provides a means of situating the work of different agencies and authorities within emergency management phases but provides no guidance as to operational practice. While it is reasonable to observe that PPRR is theoretical and AIIMS is practical, theoretical frameworks have value in guiding the planning for the necessary activities of a community faced with emergencies.

AIIMS assumes that there are 2 states of existence: incidents and normality. It notes that emergency management activity can be referred to in phases: before, during and after ‘to return to a new normality’ (AFAC 2017, p.3). The use of PPRR is acknowledged but the activities under the framework ‘may be neither linear or sequential’ (AFAC 2017, p.10). AIIMS guides combat agency activity for incidents, not the entire PPRR cycle. In AFAC (2017), ‘The wording throughout this AIIMS manual is aligned to response activities; however, AIIMS is equally applicable to recovery activities’ (p.2). AIIMS is designed for preparedness, response and recovery:

Emergency service agencies routinely work together in responding to and resolving incidents. Indeed, it is more likely the exception that an agency will work alone in preparedness, response and recovery. (AFAC 2017, p.1).

AIIMS assumes there will be inter-agency cooperation for the duration of the incident. Once the incident is over, the unity of command ends when the IMT is stood down and the different agencies resume business-as-normal.

During a large incident, an AIIMS IMT may move through the preparation, response and recovery phases. For example, during the 2019–20 bushfires in NSW, the IMT based at Katoomba was stood up because of a fire at the base of Echo Point. At the same time, the Gosper’s Mountain fire was moving south and the Green Wattle complex fire was moving north. This resulted in operations addressing the immediate threat while crews were preparing fire trails and the IMT did detailed planning for the arrival of the 2 larger fires. As the southern and northern fires arrived, personnel working the functional areas transitioned seamlessly from preparation to response. As the fire threat was reduced, some personnel transitioned to recovery. Figure 9 shows that in a very complex incident with multiple fire fronts, the overlaps between the different phases can be extreme (Simpson, Bradstock & Price 2019, pp.12–13). This is particularly true in flood events that effect different parts of river systems.

Figure 9: A typical transition from preparation to response to recovery in an emergency event.

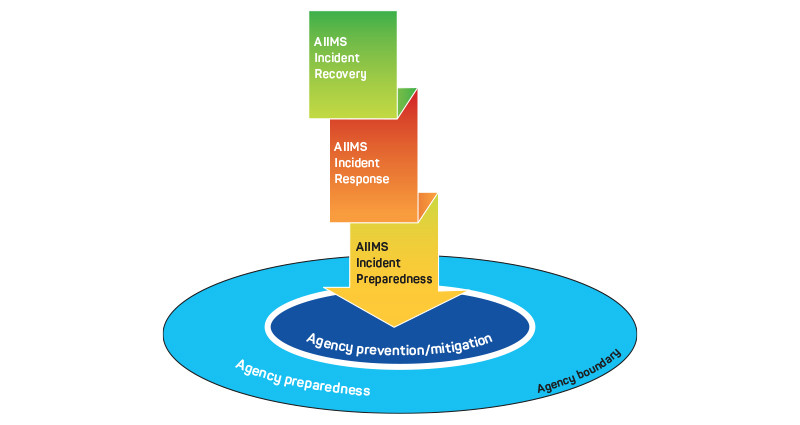

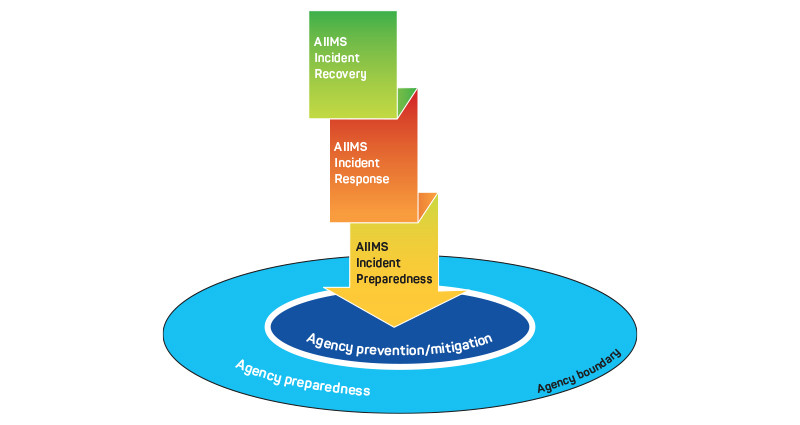

PPRR is not a practical guide for a workplan. In all agencies, not only combat agencies, prevention/mitigation runs concurrently with preparedness, often with little sense of a distinction. During incidents, recovery, at least in theory, begins when the incident starts (AFAC 2017, p 97). The NSW RFS and land management agencies, like local government and NSW Parks and Wildlife Service, have roles in prevention/mitigation. In the example provided from the Blue Mountains, for mitigation, NSW RFS and the NSW Parks and Wildlife Service conducted hazard reduction burns. Those agencies and the Blue Mountains City Council maintained fire trails and trained personnel. These agency prevention/mitigation and preparation measures are ongoing components of each organisation’s work, interrupted by emergencies when AIIMS arrangements are put in place. Mitigation is not a component of AIIMS work but preparedness is. This is different from agency preparedness work that is not concentrated on hazards of a current incident. Once an incident begins, the agency prevention/mitigation and preparedness works ceases to support the preparedness, response and recovery under AIIMS. When the incident is resolved and the IMT is stood down, the organisations resume their normal business practices (Figure 10).

Figure 10: Agency preparedness and prevention/mitigation and AIIMS PPRR in an incident. Note: the agency boundary is breached by AIIMS.

Mitigation and preparedness: whole-of-government use of AIIMS

Setting aside the organisational difficulties, the AIIMS structure offers a very sound way of managing prevention/mitigation and agency preparedness. Agencies have specific obligations in relation to mitigation. The NSW Rural Fires Act 1997 includes a legislative base for the ‘prevention, mitigation and suppression of bush and other fires in local government areas (or parts of areas) and other parts of the State constituted as rural fire districts’ (Rural Fires Act (NSW) 1997, s.3). The principal instrument provided in the Act is the Bush Fire Co-ordinating Committee (BFCC), which is tasked with the formation of Bush Fire Management Committees (BFMC) across the state (Rural Fires Act (NSW) 1997, p.3). Recommendation 7 of the Final Report of the NSW Bushfire Inquiry looks to the development of resource allocation protocols between NSW RFS and FRNSW (Owens & O’Kane 2020, p.108). However, Recommendation 8 goes much further:

Recommendation 8: That, to strengthen cross-agency accountability and deliver improved bush fire risk management outcomes:

a. BFCC members from NSW government agencies are at the level of Coordinator General/Deputy Secretary/Agency Head/Deputy Commissioner (or equivalent)

b. the BFCC ensures all Bush Fire Risk Management Plans, Operation Coordination Plans and Fire Access and Fire Trail (FAFT) Plans are compliant with the timeframes outlined in section 52 of the Rural Fires Act as soon as practicable

c. the BFCC develops a risk-based performance auditing cycle to ensure Bush Fire Risk Management Plans, Operation Coordination Plans and FAFT Plans are fit-for-purpose and any opportunities for improvement are identified and actioned

d. the NSW RFS considers the best way of enhancing the transparency of BFCC decision-making, for example by publishing BFCC membership and minutes on its website

e. the BFCC endorses the annual statement to Parliament on the likely fire risk and the effectiveness of planning and preparation

f. relevant agencies review Bush Fire Management Committee (BFMC) membership and confirm to the NSW RFS that members have sufficient discretion and authority to agree and implement risk mitigation activities at the local level

g. the NSW RFS Commissioner amends the BFMC Policy to require BFMCs to refer unresolved issues to the BFCC for resolution. (Owens & O’Kane 2020, p.115)

Recommendation 8 goes to the very heart of bushfire prevention/mitigation for agencies. Arguably, the implementation of this recommendation requires a major change in procedures, particularly at the coordination level across agencies through a whole-of-government strategy. The BFCC will depend on the cooperation of agencies without any powers of compliance and with no command-and-control functions.

The Final Report of the NSW Bushfire Inquiry also makes recommendations related to preparation. Recommendation 6 addresses what the inquiry saw as deficiencies in preparation by agencies for the recent fires: ‘The Inquiry has identified a series of initial priorities for training to ensure that firefighting practice keeps up with new and emerging research’ (Owens & O’Kane 2020, ps.101, 103). Recommendation 9 speaks to the available firefighting workforce, either from NSW agencies or from outside the state (Owens & O’Kane 2020, p.120). Recommendation 15 addresses community engagement (Owens & O’Kane 2020, p.143). Recommendation 16 looks at the need for inter-agency support for tourist bodies and Recommendation 17 seeks to address deficiencies in the provision Safer Neighbourhood Places (Owens & O’Kane 2020,ps.145, 148). Recommendations 18–33 refer to additional matters that fall under the preparation rubric (Owens & O’Kane 2020, pp.ix-xiv). Most, if not all, of these recommendations require inter-agency cooperation within a PPRR framework.

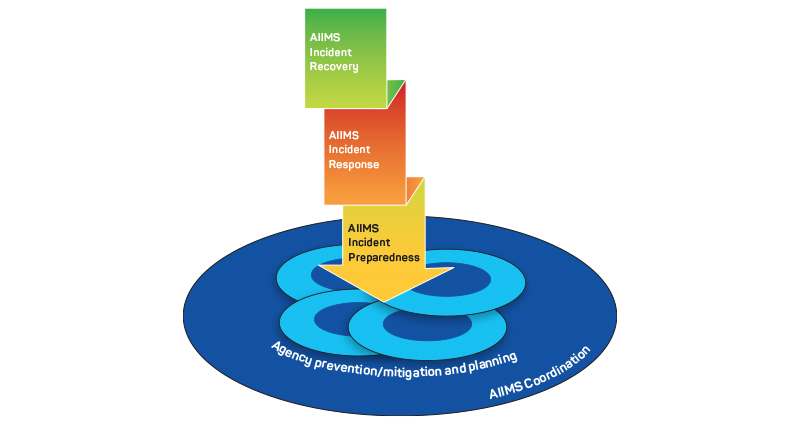

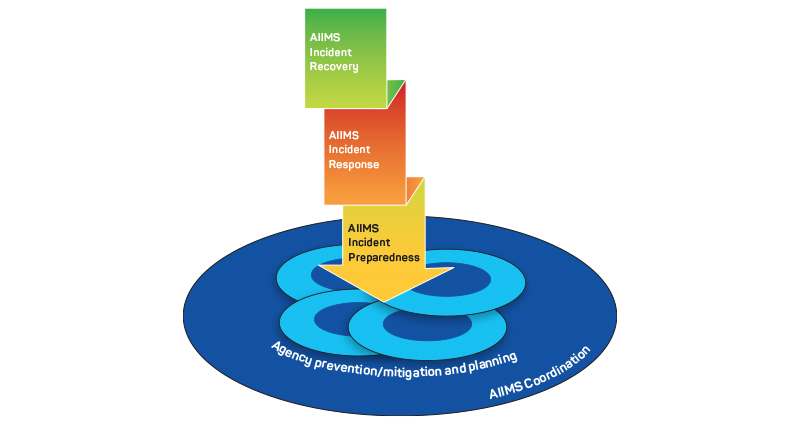

The structure of AIIMS is suited to progressing these recommendations. Current inter-agency cooperation seeks to use collaborative committees like the BFCC. Such committees, common across bureaucracies, struggle for traction because agency representatives are necessarily driven by each agency’s priorities. Figure 11 represents how, with a whole-of-government strategy, using AIIMS principles of flexibility, management by objectives, functional management structures, unity of command and span of control, governments can achieve coordination across agencies, as it does during major incidents with a command approach to breach agency boundaries and co-opt agency personnel. A whole-of-government IMT would need to be a permanent entity, supported by appropriate legislation and regulation, coordinating some of the work of current agencies. A particular advantage of using AIIMS is that agency assumptions and self-imposed limitations in scenario planning are lessened, leading to much better preparation for the worst-case scenario (Gissing, Eburn & McAneney 2018, p.7; Jenkins & Edwards-Winslow 2003, p.49; Kahane 2012; Reos Partners 2021). Deficiencies can be identified and addressed before they become problematic or even fatal. In relation to prevention/mitigation, a particular challenge is the acceptance by agencies of risk ownership. It is likely that such ownership will become clear under AIIMS (Young & Jones 2018, ps.49, 53). Resilience NSW would be an obvious body to manage this whole-of-government structure with its public focus on preparation, rescue, recovery and broader emergency management including the State Emergency Management Plan (NSW Government).

Figure 11: AIIMS coordination for state-level prevention/mitigation and planning.

Recovery: a role for AIIMS at state-level as well as in IMTs

Recovery after the 2019–20 bushfires has been problematic, in part due to the number of communities that suffered. Figures 9 and 10 show recovery within AIIMS as the responsibility of an IMT although, under AIIMS, recovery can be transferred to another organisation (AFAC, 2017, p.62). In AIIMS terms, recovery is incident specific and a responsibility of each IMT, drawing support from other agencies as needed. Figure 12 shows how the AIIMS functional areas would work in supporting recovery specific to an incident. IMTs have long lacked the resources to manage recovery. For example, in the wake of the 2013 Linksview fire in the lower Blue Mountains, a separate recovery organisation, relying on the Red Cross and local government and non-government resources, was set up. Recovery does not feature strongly in NSW RFS training for volunteers. The NSW RFS, relying on a volunteer workforce at brigade level and a small salaried staff, while having the capability, lacks the capacity to support recovery and must draw on other agencies. Even if each IMT that operated during the 2019–20 bushfires was able to handle recovery, effective coordination of resource use across NSW would still have been necessary. It is unfortunate that the terms of reference for the NSW Bushfire Inquiry excluded recovery (Owens & O’Kane 2020, p.6). A significant outcome of the experiences of 2019–20 was the recasting of the Office of Emergency Management as Resilience NSW with a specific responsibility in preparation and recovery within the PPRR framework. Empowering Resilience NSW in a whole-of-government strategy using AIIMS could provide the means to address circumstances that led to its formation. Resilience NSW has released a NSW Recovery Plan (Resilience NSW 2021). This is an admirable start, but it remains that the State Emergency and Rescue Management Act 1989 will be used to create a permanent entity to develop high-quality plans for and across NSW. When NSW faces challenges like those of 2019–20, recovery would benefit from using AIIMS command-and-control structures.

Figure 12: An example of AIIMS functional areas in support of recovery.

Conclusion

The nature of the threats to communities due to climatic events is evidenced by the 2019–20 bushfires that led to recommendations in the Final Report of the NSW Bushfire Inquiry (Owens and O’Kane 2020). The BFCC looks to implement some recommendations but its role is confined to the statutory responsibilities of the NSW RFS (Bush Fire Co-ordinating Committee 2021). The State Recovery Plan is an excellent start. A comprehensive strategic response would lie with Resilience NSW and its State Emergency Management Committee (State Emergency and Recovery Management Act 1989 (NSW), s.15). AIIMS provides a means of working across agencies to enhance the safety of communities in NSW and Resilience NSW is well placed to progress a whole-of-government response. To leave response to recommendations to individual agencies would put NSW at risk of being subject to the lack of appropriate prevention/mitigation, preparation and recovery that emerged from the 2019–20 bushfires.

There is little dispute that AIIMS is a robust and valuable system for incident management in Australia and New Zealand. PPRR, on the other hand is something of an orphan: obviously there but owned by none. Nevertheless, the value of the framework has not been seriously questioned as a conceptual framework for describing the transition from normality to disaster and back to a new normality. In many respects, PPRR operates at a strategic level while AIIMS is tactical. This paper has attempted to clarify what PPRR means during an incident. While prevention/mitigation are clearly pre-incident, preparedness has a different complexion in normality than during an incident under AIIMS. For Resilience NSW, AIIMS provides an appropriate means of carrying out recovery using a whole-of-government strategy for coordinating the work of agencies in prevention/mitigation, preparedness and recovery for the benefit of NSW.