Community participation and leadership as a shared responsibility of emergency and disaster preparedness is receiving increasing attention. This paper offers an approach informed by complexity and community development theories to support, map and gauge community-led disaster preparedness. A review of existing research, theoretical debates and primary research with communities suggests community preparedness is supported by action across 7 domains: information, networks, communication, resources, decision-making, self-organising and inclusion. These dimensions are best understood as part of a complex system; that is, dimensions interconnect and adapt in non-linear and dynamic ways. The aim of this paper is to offer theoretical foundations for work that strengthens community preparedness.

Introduction

Community engagement, participation and leadership are significant challenges to enacting shared responsibility in all aspects of emergencies and disasters. Policy makers and those on the front line of preparedness, response and recovery demonstrate a willingness to strengthen the community aspect of shared responsibility (Binskin, Bennett & Macintosh 2020). While the number of case studies of projects that have successfully enacted community engagement and participation is growing (see for example Mitchell 2019, Jolly 2020, McLennan 2020, Jewett et al. 2021) these remain to a great extent descriptive and the practices unmapped. There is also an increasing literature that attests to what might be understood as ‘culture clash’ between command-and-control processes (emergency services organisations) and ‘organic grass roots processes’ (community-based groups and organisations) (Crosweller & Tschakert 2021). This paper provides an approach for supporting, mapping and gauging community-led disaster preparedness based on research and theoretical conceptualisation of communities and complexity.

Understanding communities

Any efforts to strengthen the community aspect of shared responsibility must first define the notion of ‘community’. While a shared understanding is assumed, theorists and community development workers have struggled with the trickiness of the concept of ‘community’. In contemporary uses, the concept of ‘community’ is often ill-defined and infused, particularly in advertising and media, with romanticism (Ewart & McLean 2019; Rawsthorne & Howard 2013; Germov, Williams & Freij 2011). Geographic descriptors provide limited insight into how communities are constituted, experienced or function. Binary descriptors (resilient/vulnerable or prepared/unprepared) are also unhelpful. Understanding the contours of community processes is, however, vital if we are to support community actions and shared responsibility in disaster events. This is far from straightforward as each community is unique, despite often exhibiting similar contours (Taylor 2015, Ife 2016). Communities are socially produced, not an object to be acted upon. It is for this reason that policies that ‘roll out’ projects in a cookie cutter fashion often have very uneven traction between locations. These approaches are largely short lived with outcomes shaped by the project or funding logics rather than community priorities and processes.

There is no doubt that the notion of ‘community’ holds significant social, psychological and political power. In terms of shared responsibility, community is an ‘elastic’ concept (Collins 2010) that can be usefully mobilised to support social action. It is through dialogue with community members that shared understanding emerges, challenging the assumptions about community and power.

Community development theory and practice

Working with communities is an approach that is being embraced by many organisations and front-line workers, however, this is often unsupported by community development theoretical insights. The approach presented here adopts a relational lens, ‘a way of thinking about community that stresses the importance of relationships and connectivity’ (Oliver & Pitt 2013).

Effective community development practice, rather than following ‘rules’, requires Bourdieu’s notion of ‘a feel for the game’ (habitus). By observing sports people, Bourdieu (1990) argues that excellence arises from ‘a feel for the game’ that integrates both knowledge and technical skills with creativity, improvisation and inventiveness (Rawsthorne & Howard 2013). What is implicit in this metaphor is that developing a feel for the game in working effectively with communities requires practice. It is this experimental element of work with communities that draws heavily on reflection and creativity. If every community is unique then every engagement needs to be unique. This work requires an ability to shift power, to deeply listen and to participate.

Those seeking to strengthen community participation in shared responsibility need to develop a nuanced understanding of power, most particularly their own professional power to shape experiences (Crosweller & Tschakert 2021, Moreton 2018). Rawsthorne & Howard (2013) argue that shifting power is fundamental to community development practice (see also Howard & Rawsthorne 2019). This includes paying attention to symbolic power embodied in physical space (who sits at the head of the table) and uniforms and expertise (whose perspectives are privileged). It is also about paying attention to structural power such as who chairs meetings, how information is controlled, the balance between community members and ‘experts’ and, importantly, who sets the agenda. Shifting power is both enabled and demonstrated through the practice of deep listening (Oldam et al. 2020, Bacon 2013). This involves ‘loitering’ in communities (Howard & Rawsthorne 2019, Ledwith 2016), spending time in the everyday life of the community, not merely engaging with the community instrumentally around an agenda. Calling a community meeting will quickly surface the known or traditional leaders in communities (Sampson et al. 2021) who are likely to be very helpful to mainstream efforts in strengthening communities, but deep listening is also about taking time to seek out people and experiences that are not usually included (Howard & Rawsthorne 2019, Bacon 2013). This is particularly important given that marginalised sectors within communities are often those most affected by disasters (Mayer 2019, Crosweller & Tschakert 2021).

A practical way that deep listening can be incorporated into project development is to include a ‘discovery’ phase in the planning (Howard & Rawsthorne 2019, Ledwith 2016). The specifics of the remainder of the action or intervention should be subject to what is learnt in the discovery phase. Strengthening community participation in shared responsibility requires facilitation skills. This is not only understanding meeting procedures but creating environments that are safe for participants to share perspectives; environments in which ideas can be explored. This could include creating non-meeting-related opportunities for participation, such as community events or competitions or working through schools or sporting clubs. There are many examples to draw on; the approach will be informed by the deep listening.

Supporting community action for disaster preparedness

Drawing on theoretical insights and empirical research (Howard et al. 2014, 2017a, 2017b, 2018, 2020, 2021), 7 dimensions of community action have been identified that support disaster preparedness. For those working with communities, these domains provide an adaptable approach to map, support and gauge community-led disaster preparedness. A singular, static, ‘cookbook’ model is not recommended, and this is not the only way to strengthen community-led disaster planning. The approach has guiding principles based on research and theory about community development, participatory planning and social change that informs its theory of change, including that:

- change takes place when local communities can express their needs and have decision-making power to influence planning

- to enact change, local knowledge, participation and decision-making needs to be connected and integrated with formal regional, State and national preparedness, response and recovery approaches

- recognising, supporting and building on existing community strengths embeds change and supports sustainability in local planning.

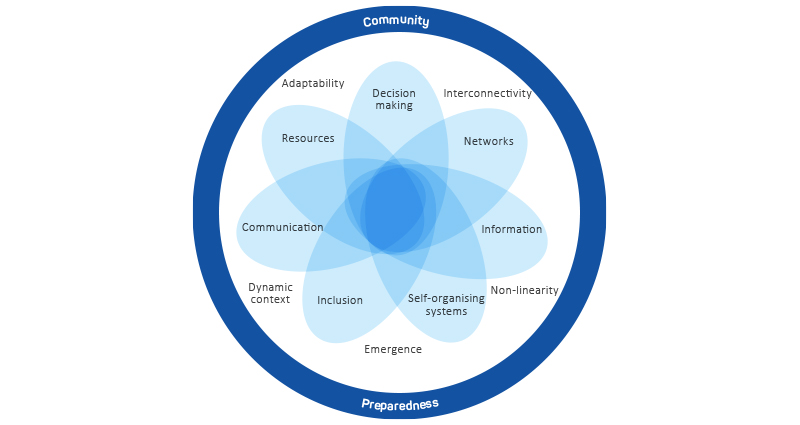

Figure 1 places the 7 dimensions within a complex system and highlights the relationships between the dimensions that are interconnected, non-linear, dynamic, adaptable and emergent. Complexity theory presents an alternative to reductionist approaches that seek to simplify difficult or multi-layered problems (Turner & Baker 2019). It acknowledges and values the messiness and uncertainty that are inherent in social life. Through this lens, it is possible to incorporate the changing, unexpected and only partly knowable characteristics of communities. While the goal of traditional efforts to reduce complex problems into simplified, understandable and quantifiable parts seek to ‘provide us with at least the illusion of control’ (Pycroft 2014) or ‘to facilitate ease of … action’ (Hager & Beckett 2019), complexity theory argues that to do so is inherently ineffective, due to the ongoing influence of excluded elements. The 5 core concepts of complexity theory are particularly helpful to understand community preparedness.

Figure 1: Community action on disaster preparedness.

Interconnectivity

Fundamental to the notion of complexity is the idea of interconnection between elements within a system (Cilliers 1998, Pycroft 2014), and between multiple systems that may be nested (Byrne 1998). Most importantly, the concept of interconnectivity reflects active processes occurring over time, as opposed to a static structure. Cilliers (1998) notes that the interconnections in complex systems occur primarily between proximal elements (in this context, in relationships at the local level). This is an important aspect of community preparedness as it emphasises the importance of local action in building preparedness and may go some way to explaining the challenges faced by those who attempt to impose interventions from afar.

Non-linearity

The interconnections between elements in complex systems occur in non-linear ways. In contrast to linear and predictable approaches where interventions can be designed, implemented, measured and evaluated against predicted outcomes, community life features non-linear processes with delays, reversals, multiplicity and the (often intangible) influences of human relationships. In complex systems, non-linearity means that cause-and-effect relationships may be difficult to track. Furthermore, the non-linear nature of interactions results in consequences that may be disproportionate and difficult to predict. Adopting a sensitivity to complexity and non-linearity is a marked departure from formalised planned approaches. As an example, a community gathering to celebrate the beginning of the rebuild of a community hall can be an opportunity to build inclusion (through a smoking ceremony lead by local Indigenous peoples) or strengthen networks (through inviting a club or association to cater for the event). Coincidental or unexpected outcomes may emerge, with local Aboriginal and Torres Straits Islander residents sharing their knowledge of Country with members of traditional community-based organisations whom they might not normally have contact with.

Dynamic context

Byrne and Callaghan (2014) suggest that systems have narratives, with histories and futures. As such, the structure and activity of communities and organisations, as well as the wider environments in which they are situated, can be understood to exist in a dynamic state in both time and space. While a system’s history can suggest trends, ‘(t)here are things we do not know which might have a determinant influence on future trajectories’ (Byrne & Callaghan 2014). Earlier iterations of systems theory proposed that systems seek to maintain a ‘dynamic equilibrium’ in response to stressors. But Cilliers (1998) argues that disequilibrium itself can, to an extent, be energising.

Equilibrium, symmetry and complete stability mean death. Just as the flow of energy is necessary to fight entropy and maintain the complex structure of the system, society can only survive as a process. It is defined not by its origins or its goals, but by what it is doing. … (and) to yearn for a state of complete equilibrium is to yearn for a sarcophagus. (Cilliers 1998)

Moreover, the dynamic interplay between elements of the system, and between multiple systems, can offer hope for future trajectories as ‘working with, rather than against (notions of ambiguity and complexity), will produce more creative and innovative responses’ (Stalker 2003).

Emergence

Emergence acknowledges the way in which the interconnected relationships and processes that occur within a community are productive, bringing about a shared and locally informed identification of problems and resources. As an outcome of the dynamic and non-linear interconnections of a community, the emergence can be seen of new ways of being, doing and knowing, in a process of ‘co-evolution’ (Allen 1997, in Byrne & Callaghan 2014). The concept of emergence incorporates both uncertainty and unpredictability. This is at the heart of system complexity, where ‘simple bits interacting in a simple way may lead to (a) rich variety of realistic outcomes’ (Johnson 2007, in Byrne & Callaghan 2014).

Adaptability

Binary understandings (‘resilient/vulnerable’ and ‘formal/informal’) are unhelpful in achieving effective and sustainable outcomes in community development. Using the lens of complexity theory, it is possible to recognise flows of power that are interconnected, dynamic and non-linear. The combination of the characteristics of a system allow it to adapt in response to challenges, changes and threats. In contrast to linear cause-and-effect models, adaptive systems are influenced by multiple interactions and effects that may be disproportionate. While this makes outcomes difficult to predict, the decentralised nature of such systems fosters adaptability as the absence of a single ‘control mechanism’ allows other parts of the systems to innovate and compensate (Pycroft 2014).

Dimensions of community action

Despite the complexity of communities and disaster events, we repeatedly see communities act collectively. There are 7 broad dimensions that contribute to disaster preparedness that we have identified through review of existing research, theoretical engagement and primary research.

Information

Information is generated before, during and after crises by multiple players. Central control of information is impossible during any of these stages. Without information, or with incorrect information, community action may be hindered, ineffective or, at worst, dangerous. It is vital to understand how information moves within a community as it is a key domain of action. Information needs to be understood not only as a product but also as a process. Mapping how information flows within communities is a useful tool in strengthening community-led disaster preparedness (Chazdon et al. 2017). Those interested in supporting community-led disaster preparedness need to be attentive to what sources are used to generate information with a view to supporting the local production of information. In this way, communities can be understood as consumers of information and also producers of information. This mapping identifies the sources and the credibility of the information and how people put this information to use.

When communities are producers of information it is more likely that this information translates into action. Policy makers and emergency services agencies rely on information provision to change behaviours. The risk is leaving communities feeling bombarded by information products if attention is not paid to the coordination and relevance of information. Developing trusted information sources through ongoing discussion that includes community members and other stakeholders supports effective information flow and utilisation.

Networks

The ability to map and mobilise (or tap into) networks is important. Strengthening community action requires an in-depth knowledge and understanding of the strength, diversity, density and interconnections of local networks. These networks may be formal or informal and are likely to shift over time. Taking the time to listen and observe community networks is important to understand the historical processes that play out in community actions. The integration of formal emergency services agency networks and informal community networks supports community participation in shared responsibility. This integration needs to acknowledge the power differentials and the historical processes that make it so challenging.

Networking enacts collaboration that ideally supports emergent community action that is flexible, adaptive and inclusive. Strengthening community-led disaster planning requires collaboration based on co-configuration and distributed expertise, that is, the actions reflect the ideas of many ‘experts’ particularly residents whose knowledge is based on lived experience. This means there is no one prescribed approach as it will differ in different settings. The ability to mobilise networks requires a combination of values (a commitment to working with others), skills (the capacity to work with others) and structures (the existence of locally tailored processes). A particular challenge is letting go of control and feeling comfortable as new ideas or directions emerge from bringing people together. The most creative and exhilarating partnership practice requires highly skilled ‘boundary crossers’ engaged in expansive learning from others.

Decision-making processes

Decision-making processes are vital to realising community-led disaster preparedness. This is not about how decisions are made within formal structures but about who is included in the decision-making process, where decisions are made and the transparency and accountability of these decisions. It is often a point of conflict between emergency services agencies and other systems and community processes, due to the traditional command-and-control hierarchy. Rather than decisions being made by external experts, strengthening community-led preparedness requires collaborative planning processes in which decisions are reached over time through consensus. Conflict occurs when community-driven decision-making is overridden or ignored by formal systems.

Communication

The importance of communication in strengthening community-led disaster preparedness can be obvious, however, more effort is needed to support communication processes rather than products. During emergencies and disasters, communication prioritises the delivery of messages (one way). However, effective communication is multi-directional, involves institutions, communities and stakeholders in a local area. There is a wealth of important knowledge within communities that can be harnessed for all elements of the disaster cycle as well as localised communication pathways. Who is included in which discussions and planning processes now and who else needs to be included for integrated communication are important questions. Closely related to information, communication, is deliberative and ongoing with the most important work being undertaken outside response times.

Self-organising systems

Self-organising initiatives or systems are well recognised in disasters, particularly in the response and recovery phases. Often this is an imperative given that local people are ‘on the ground’ when disaster hits, even when it is anticipated. Australia has a long history of communities self-organising around disasters and this is viewed as a valuable cultural practice (Handmer & Maynard 2021). Self-organising is important in the preparedness and prevention phase as well. Communities self-organise across a diverse range of issues such as the physical environment, the built environment, social connections and people’s wellbeing. These self-organised systems should consider disaster preparedness as part of their work. Identifying, supporting and integrating existing self-organising systems during preparedness has the added benefit of strengthening community capacity in response and recovery.

Resources

Resources are commonly viewed as significant to community engagement by emergency services agencies locally and globally. These resources historically have been material resources (sandbags, generators, boats) but, more recently, a significant focus on mental health resources has emerged. There needs to be an additional understanding of resources related to access to funds, time and expertise. Long-term community preparedness actions that rely only on goodwill or self-interest is unlikely to create sustainability. Time and local knowledge are resources often overlooked and taken for granted in disasters. It is vital these are acknowledged and supported.

Philanthropic donations as well as food, clothes and furniture donations risk overwhelming communities. Organising, distributing and managing the inundation of donations and support requires robust, reliable and already established local social and economic infrastructure. Long-term community action sets up local ways (including local groups, organisations, networks and relationships) to manage and, in some cases, resist the well-meaning but potentially chaotic convergence of assistance during and just after a disaster.

Inclusion

There is clear evidence within Australia and internationally that those at the social margin are often the groups and community members most affected by disasters. For this reason, reducing social exclusion needs to be a priority in community preparedness. Disaster preparedness should specifically include diverse groups within the community. In each community it is likely that different groups will experience exclusion. The experiences of First Nations people, people with disability and people experiencing homelessness are commonly overlooked in planning and research.Genuine inclusion is only achieved when formal structures are disrupted and alternative processes are introduced. Mainstream processes such as meetings, community workshops and committees are effective in supporting disaster preparedness with those already engaged in these processes (Sampson et al. 2021). Again, long-term community action needs to seek out the people who are not normally involved, take discussions outside of the traditional forums and listen deeply to the experiences of excluded groups. This requires loitering or proactive outreach (invited) in places such skate ramps, social groups, shopping centres or gathering places used by local residents of diverse backgrounds.

Conclusion

The frequency and extent of emergencies and disasters is likely to increase in Australia with significant social, economic and political costs. Enacting government policies of ‘shared responsibility’ is proving difficult with a significant gap between policy and practice in community participation and leadership in preparedness and recovery. This paper contributes to efforts to bridge this gap, drawing on theoretical insights on community development and complexity. It outlined a framework to support community-led preparedness through action across 7 interrelated dimensions. Supporting communities to pay attention to these dimensions strengthens

their capacity to prepare for and recover from future disasters.