Residents look to state leaders during high-risk events for advice and guidance. Previous events have reinforced the vital role that governments play in delivering emergency messages. Creating meaningful messages during emergencies is vital to inform affected populations and to encourage them to take appropriate actions. In February 2022, South East Queensland experienced a significant flooding event that resulted in the loss of life and property. This study identified that conflicting information was released due to the uncertainty of the weather event. Many residents used Twitter to post about what was being experienced, creating a real-time display of what was happening. This study analysed the public-facing government media conferences held over 4 days against Situational Crisis Communication Theory1 and compared the response to Twitter posts during the key days of the February flood. The study found an overwhelming use of the theory’s denial and diminishment approaches used by some communicators combined with the rebuilding approach used by others. This had great potential to cause conflicting and confusing messages. This research is important because language encourages people to believe that floods can be prevented. Conflicting messaging can cause significant harm by not providing clear direction regarding evacuation and other safety measures.

Background

In February 2022, areas of South East Queensland experienced heavy rain that resulted in significant localised and river flooding. Several lives were lost in this event, including that of an SES volunteer (QFES 2022). While residents watched the water rise, the messages from authorities suggested the event was ‘unprecedented’ and not similar to past flooding events (Nally 2022). Eleven years prior, South East Queensland was inundated by a ‘wall of water’ (AIDR n.d) that resulted in the rapid rise of the Brisbane River, primarily from dam releases, and inundated more than 28,000 homes (AIDR n.d). A Commission of Inquiry was conducted to investigate the cause of the flood and this cemented the event in the memory of residents. The inquiry found that the dam manuals required updating to mitigate future floods. This contributed to a popular mindset that floods will be prevented (Cook 2018). Despite the short time between events and the similarities felt on the ground by residents, the events were scientifically different. The Queensland Premier commented, ‘this is not the same situation as 2011’ and ‘there is no concern for alarm’. However, online platforms, particularly Twitter, showed scenes experienced by residents of the river breaching banks and inundating properties.

This research considers crisis communication by exploring how Situational Crisis Communication Theory (SCCT) was reflected in 6 media conferences delivered on the 4 prominent days of the flood event. This study analyses the conferences by comparing the key messages to social media commentary, particularly visual evidence on Twitter under the hashtag #bnefloods. It examines the role social media could play in government crisis communication messaging during life-threatening events.

Media conferences have a significant role in Australia and have increased in importance since 2010, when events began to be live-streamed (Queensland Police Service n.d.). Although people in Australia do not necessarily watch entire media conferences regularly, live-streaming has increased in use since the COVID-19 pandemic (Villegas 2020). Audiences have become familiar with watching full-version broadcasts rather than viewing a compressed version delivered in the news. Media conferences can be highly performative and play a part in public politics (Craig 2016). They have played a significant role in providing information to the public, are a public spectacle and a symbolic display of political accountability (McLean & Ewart 2020). In Queensland, media conferences are typically run by the Premier and the State Disaster Coordinator who can propose resolutions to issues or approve warnings advice (Craig 2016, McLean & Ewart 2020).

There is significant scholarship on crisis communications, particularly related to how an organisation should communicate. It is essential for organisations to actively listen to and engage in social media discussions to assist in maintaining reputation (Coombs & Holladay 2014). Although its use pre-dates social media, SCCT can also help retain reputation by linking responses to crisis types (Coombs 2017). The communication approaches are set out as 4 options:

- denial

- diminish

- rebuild

- bolster.

Denial is where the communicator denies the event, the severity of the event or any responsibility for the event. This is not a recommended approach during an emergency situation as it can reduce trust as the crisis unfolds.

The diminish approach minimises the event's effects. It is also not recommended during emergencies as the public expects communicators to show control regardless of their ability to take control.

Rebuilding is a recommended approach where the communicator takes responsibility and action. Ultimately, it is about showing control and guiding those affected to a desirable outcome.

Bolstering is where the communicator reminds audiences of the good work previously done to maintain reputation. This approach should not be used on its own but should be combined with one of the other 3 approaches.

SCCT has been used to analyse crisis responses in scholarship, particularly regarding organisations’ responses. This research used the theory to analyse government media conferences. Stakeholders are at its core, and the theory encourages crisis communicators to place affected stakeholders first (Coombs 2017).

Methods

Media conferences were viewed on the Queensland Premier YouTube channel, where they were presented in full and are unedited. Six media conferences over 4 days were considered. The conferences related to the weather event and subsequent flooding between 25 and 28 February 2022. Drawing from Villegas (2020), the videos were analysed by taking notes on the communicators involved, their role, the key message and the SCCT approach used. Further, tensions exhibited through body language or vocal tone were also noted to bring attention to conflicts that may occur in the delivery of the message.

Netlytic2 was used to collect posts from Twitter between 25 and 28 February 2022. A total of 43,233 public tweets were collected using a Twitter API. The tweets were first analysed by date. The majority (n = 22.68k) was posted on 27 February, which aligns with the peak of the flood and when members of the community were most affected. Tweets were then analysed for sentiment and theme to allow examples to be extracted and used as comparisons for key messages from the conferences.

Findings

Table 1 shows the communicators at each media conference, their role and when they were present. Despite being lead authorities in the response, there were some representatives not present at any media conferences.

Table 1: Role and attendance of each speaker at the media conference.

| Queensland Premier | The Premier is the state leader, an authoritative figure who informs people of what to expect. |

26 February PM |

| The Hon. Mark Ryan MP | Minister for Police, Fire and Emergency Services and Minister for Corrective Services who provided an overview of the situation. | 26 February AM |

| The Hon. Mark Bailey MP | Minister for Transport and Main Roads who provided information on road and transport impacts. | 27 February AM |

| Lord Mayor of Brisbane | The Lord Mayor is the elected leader for the City of Brisbane. While his role was not clear, he was introduced by the Premier to inform on local impacts. | 27 February AM |

| Bureau of Meteorology Representative | Bureau representatives were different on each day and they provided information about predicted flood levels and rainfall. | Present at all media conferences |

| Queensland Police Service Commissioner | The Commissioner provided updates on the loss of life, searches for missing people and other police-related matters. | 26 February AM/PM 27 February AM/PM 28 February |

| State Disaster Coordinator | The Coordinator is the lead for the response and recovery who provided an overview on the approaches being taken. As a Deputy Commissioner of Police, he also provided some statistics related to police activity. | Representative |

| Queensland Fire and Emergency Services Commissioner | The Commissioner provided an overview of swift-water rescues and the SES response and rescue. | Present at all media conferences |

| SEQ Water | SEQ Water representatives (including water experts and dam experts) provided information on dam levels, release approaches and the implications on flooding. | 26 February PM 27 February AM/PM 28 February |

Table 2 shows that the SCCT communication approaches were mixed and that there was a shift in approaches from 26 February PM to the denial and diminish approaches.

Table 2: Use of SCCT communication approaches in media conferences.

| Date | Denial | Diminish | Bolster | Rebuild |

| 25 February | √ | |||

| 26 February AM | √ | |||

| 26 February PM | √ | √ | ||

| 27 February AM | √ | √ | ||

| 27 February PM | √ | √ | √ | |

| 28 February | √ | √ |

25 February

The media conferences were run in a similar format each day. They generally began with comment from the leading political representative. There was no political representative at the first media conference. Instead, the Bureau of Meteorology was the lead speaker and handed over to emergency services representatives. The primary SCCT approach used was the rebuild approach. All participants took control of the message and focused on the severity and dangerous nature of the event. There were hints that the event was going to have a serious effect, as seen in this quote from the Coordinator:

As you've heard from.. the Bureau of Meteorology, it is expected to continue for some time, yet it won't be over for a while, and we're coming into the night, and of course, that makes things more difficult.

In this 15-minute media conference, the word ‘dangerous’ was used 7 times and ‘life-threatening’ was used 6 times. This suggests that the impending weather event was substantial and likely to have significant consequences.

26 February AM

On 26 February, the media conferences occurred in the morning and afternoon as the weather intensified. The Minister for Police, Fire and Emergency Services led the morning media conference. The minister used the rebuilding approach when delivering the news of the death of 2 people in flood waters, particularly an SES volunteer who died while on duty. This approach was reflected in his comments:

The event is not over, though and for many parts of South East Queensland, this is the biggest flooding event that they will see for a decade.

People need to be really aware of their circumstances, continue to listen to the authorities and make very sensible decisions about what they are doing.

These comments are consistent with commentary on Twitter during the morning of 26 February (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Tweet 26 February, AM.

The Bureau of Meteorology was consistent in using the rebuilding approach by warning residents of the impact the flood could have on communities in the coming days:

Just know for the next 24 hours we're in a high flood risk with the potential for a lot of flooding around the south-east and it's not just going to stop tomorrow once this weather system moves on this flood waters are going to continue.

The overall tone of this conference was of sadness and assertiveness perhaps due to the deaths. However, journalists asked questions about comparisons to the 2011 floods. The Bureau of Meteorology representative stated:

In comparison to 2011, every location is different … all the flooding that happened across the Lockyer Valley as of yesterday again very similar though some of the peaks were just shy of what happened back in 2011.

The prominence of the rebuilding approach in this conference suggests a significant event and that residents should be on high alert. The theme of danger and severity are continued with the use of words such as ‘dangerous’ (used 11 times).

26 February PM

The Premier led the afternoon media conference. This was her first appearance for this weather event. In her opening statements, she displayed the denial approach through comments such as:

I know this is of concern to many people who have experienced 2011, Please there is no concern for alarm.

However, the Bureau of Meteorology spokesperson took on a rebuilding approach by raising concerns about safety and possible similarities to 2011:

With many catchments now saturated, there is a potential for dangerous and life-threatening flash flooding … 2011 levels for both these catchments are still much higher but again, rain is still falling across these catchments.

There was less focus on danger at this conference. The Bureau of Meteorology, the Coordinator and the Queensland Fire and Emergency Services Commissioner used the word ‘significant’ to describe the flooding. The word ‘evacuation’ was used 6 times. Five of these mentions were by the Coordinator. The Premier mentioned ‘evacuation’ once related to Gympie. There was no advice on where evacuation centres were located. The Coordinator mentioned evacuation information was available online.

27 February AM

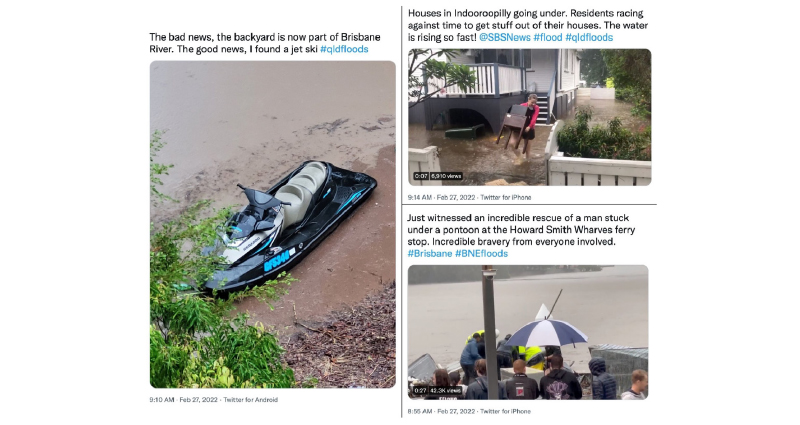

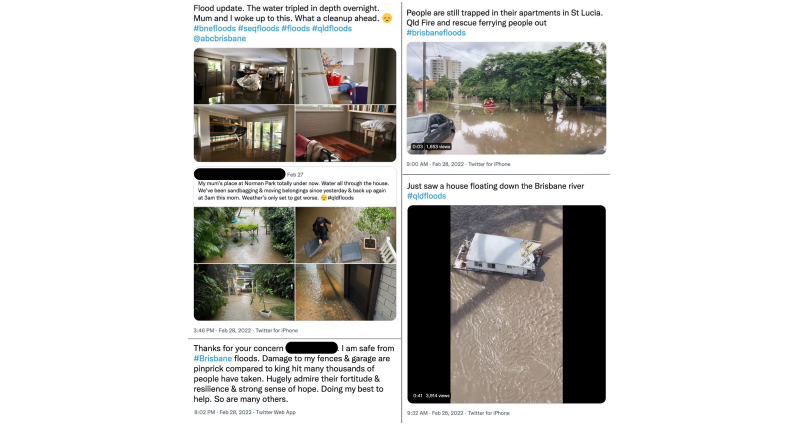

The critical issue with the denial commentary from 26 February PM was that many residents awoke to significant flooding. This was represented in tweets shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Tweets 27 February AM.

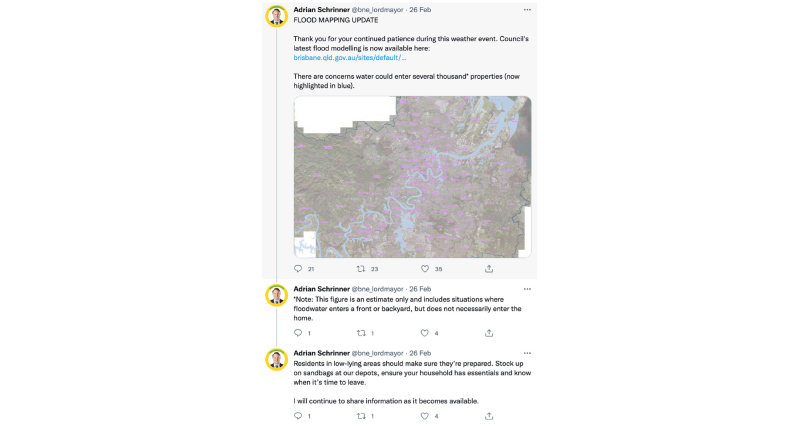

The Premier led the morning media conference on 27 February and was joined by the Lord Mayor of Brisbane. The presence of the Lord Mayor is significant as he had issued a tweet (Figure 3) that morning about the potential inundation of thousands of homes. This tweet is consistent with the rebuilding approach in that it provides information on what to expect, where to get help and evacuation advice. However, he used the bolstering approach at the media conference by reminding people to stay home as they did during the pandemic. He moved to the rebuild approach when he reminded residents to stay safe. He also talked about the difference between the 2011 flood, which led to the denial approach.

Figure 3: Tweets by Brisbane Lord Mayor Adrian Schrinner.

Police provided information on 2 more deaths. The police contribution used the rebuilding approach. The Coordinator and the Police Commissioner focused on the need for everyone to stay off the roads and away from flood waters. There remained a level of emergency in delivering this information.

During this conference, the word ‘evacuation’ was used only 4 times. The first mention was by the Premier regarding the Gympie evacuation centre and the evacuation orders the day prior. The next 2 mentions were by the Coordinator, who gave numbers of people in evacuation centres across Queensland. The final mention was from the Lord Mayor of Brisbane who included the location of an evacuation centre in Brisbane. There was no indication for people to be ready to evacuate or what to consider when deciding to evacuate.

27 February PM

By 27 February PM, the weather event was increasing in magnitude. In an opening statement, the Premier encouraged residents to consider evacuation:

Now is the time to start thinking about your safety plan.

However, by this time, many residents were already trapped by floodwaters, as seen in tweets such as:

Figure 4: Tweet 27 February PM – 1.

The police appealed to the public to take the flooding seriously as there were several incidents where residents had to be rescued due to complacent conduct. The Police Commissioner was stern in the delivery of this information and stressed the severity of the situation.

Emotions were more obvious throughout this media conference, with questions from journalists becoming heated. The Premier was asked about water releases from dams and how the actions aligned with the updated dam manual that was an outcome of the Queensland Floods Commission of Inquiry. SEQ Water provided information on how the dam works, but journalists raised questions about why the city flooded again despite an inquiry to mitigate future floods.

The Premier’s advisor attempted to wrap up the conferences as the Premier was due to meet with the Prime Minister. However, journalists stated that the flood crises was of greater importance given that people had their homes flooded 11 years ago and were going through the process again. A few more questions were asked but the conference was brought to a close.

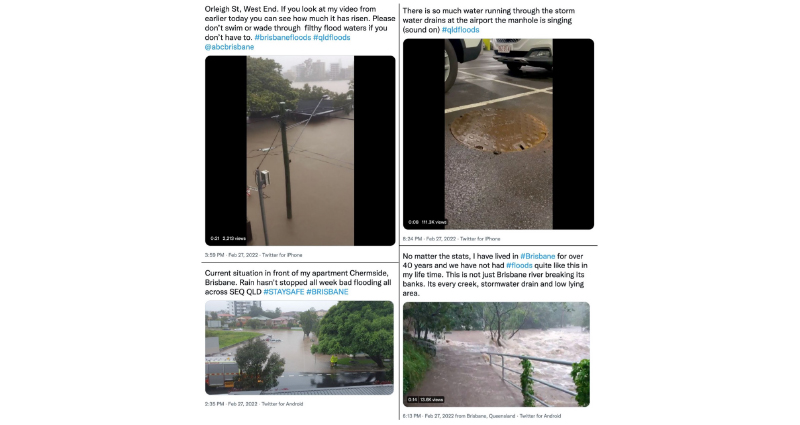

On Twitter, Brisbane residents posted images as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Tweets 27 February PM – 2.

28 February

On the morning of 28 February, Brisbane experienced further flooding and residents were alerted or awoken overnight by an evacuation alert issued through the Brisbane City Council text message service (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Brisbane City Council text message alert.

The Premier opened the media conference with a reserved tone. She discussed the impact of the event on residents and on infrastructure. Her opening statement included the number of emergency calls received by Queensland Fire and Emergency Services and SES and the Queensland Fire and Emergency Services Commissioner provided specific numbers.

Questioning from journalists was calmer, but there was persistent questioning regarding water releases from dams and subsequent flooding. The Premier appeared frustrated and one journalist highlighted that the Premier appeared dismissive of the weather event on Saturday. The Premier responded that she did not downplay the severity of the event. Further conflict was witnessed in this conference when the Bureau of Meteorology representative stated that they alerted the Queensland Government of the potential for heavy rainfall on the Tuesday of the week prior. Words such as ‘unpredictable’ were used often in this conference. The Premier talked about ‘mother nature’ 7 times, perhaps to highlight that we have no control over such incidents.

On Twitter, the trending discussion related to the lateness of the evacuation alert (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Tweet 28 February – 1.

Also, on 28 February, images posted on Twitter showed damage and devastating scenes experienced by residents (Figure 8).

Figure 8: Tweet 28 February – 2.

Figure 9: Tweet – disaster language.

Discussion

Media conferences are highly performative and strategic events and give governments control over the message being delivered (Craig 2016, McLean & Ewart 2020). In this study, the contradictions noted in conferences on 26 February do not support the level of control that should be delivered in government-provided information. Media conferences should show the support between the authorities, and all should point to a unified outcome (Craig 2016). In the earlier conferences, the consistent use of the rebuilding approach creates a sense of harmony within the messaging. The message is that of a substantial weather event that will likely cause significant flooding. However, this approach did not flow through to the later conferences. Instead, the denial and diminishment approaches became prominent.

Challenging questions from journalists are an example of what Coombs (2017) calls a ‘challenge paracrisis’ that occurs when a stakeholder publicly claims the organisation is acting irresponsibly. The Premier and SEQ Water responses on 27 and 28 February align with ‘refutation’. Coombs (2017) explains this to be when the responder claims the challenged information is invalid and that they are compliant with the expected actions. Instead, this appears as conflict in a publicly facing space such as a live-streamed conference. Although media conferences are scripted with key messages for news reproduction, the events being live-streamed give the public access to greater detail presented, along with the questions from journalists.

Media conferences can be referred to as ‘rituals of affliction’ (Cottle 2006, Villegas 2020) and are held for citizens, journalists and other stakeholders during events. A media conference, as a ritual of affliction, is described by Villegas (2020) as a way to activate processes to respond to trauma. They can be used to prevent future concerns, perform political accountability and require a ‘responsible person’ (Villegas 2020, p.356) to generate public action through meaningful advice. In the conferences viewed for this study, the Premier is the responsible person. She is the one the public looks to for information on how to act. The contradictions and conflict presented in the conferences from 26 February PM are at odds when her role is to provide stability (e.g. the lack of evacuation information). Water was beginning to flood homes so evacuation advice would be expected at this stage of the conference proceedings. Although evacuations are the responsibility of local government, the Premier has a significant profile and influence to support and deliver this messaging.

The appearance of the Lord Mayor on 27 February added to the confusion given the day prior where the Premier had stated there was ‘no concern for alarm’. The change in messaging from the Lord Mayor's tweet to the information delivered at the conference added to the confusion. Cook (2018) discusses the need to change the language used during events. Reference to ‘one-in-one-hundred-year’ or ‘unprecedented event’ has little relevance and can confuse the public. Although the weather event was scientifically different from 2011, people’s flood memory can influence society more than the scientific explanation for the weather (Cook 2018). The collective memory of people living in Brisbane is of a recent flood that resulted in the loss of life and property and the significant disruption to everyday activity. By focusing on scientific explanations and taking what could be regarded as a dismissive stance to prior flood events, authorities created uncertainty within the community, as evidenced by the collected tweets in this study.

Although most of the tweets related to this study were positive in tone, they also indicated confusion. This was represented in the apparent complacency shown by police in the 27 February PM conference. The late notice of evacuation was reflected in the number of calls to the SES that were received on the evening of 27 February. The SES received 2,200 requests for assistance; 41% of these callouts occurred in one night (QFES n.d). The Twitter commentary raises questions regarding the approach taken by communicators in conferences when crises occur. It highlights the challenges faced when the public is relying on flood memory to make comparisons. While it is clear that the communicators involved in these conferences were attempting to provide truthful and useful information to clarify the differences between the 2 events, this attempt created confusion.

Conclusion

This paper offered commentary and analysis of the Queensland Government media conference response to the 2022 Queensland floods. It concludes that taking multiple approaches to crisis communication can cause confusion. A combination of the denial and diminishment SCCT approaches was noted despite the desired rebuilding approach having been established. It is important for an organisation to focus on a consistent rebuilding approach when communicating about a crisis. Conflicting messaging can potentially put lives at risk (Miles 2022). Social media platforms must be used and acknowledged by communicators when delivering public safety messages. This highlights the challenges facing communicators when explaining scientifically specific weather events. Further research is required to cross-examine crisis communication approaches based on crisis type and location, particularly regarding the effect past disaster history can have on public responses to official messaging. This analysis found that when drawing from SCCT approaches, one approach should be taken by all parties. There should be unity in the delivery of messages to avoid complacency because conflicting messaging can cause harm through a lack of clear directions regarding evacuation and other safety measures.