An effective alerting process is an essential component in emergency and disaster management. Based on a qualitative survey conducted in 5 countries (Australia, Belgium, France, Indonesia, the USA), this study looked at the organisational, socio-political, technical and human aspects inherent in the tools used for warning systems currently in place. This work highlights the similarity of organisational objectives, but also the importance of political choices linked to national culture and the disparity in terms of integration of technological tools. It was found that none of the 5 countries had completed the digital transition of its alert systems. In the future, it will be a question of better linking prevention, technical tools and end users.

Introduction

An effective alert must provide timely information that helps people prepare adequately for an emergency or disaster (Arru, Negre & Rosenthal-Sabroux 2018). However, there is great diversity in the implementation of this process, particularly in areas of alerts, the doctrine, the number of stakeholders authorised to disseminate alerts, the modes of communication and the dissemination tools used (Sorensen 2000, Vivier et al. 2019). Since the early 2000s, changes in communication technologies have opened up new perspectives and issues in the fields of alerting and crisis management. Social networks, mobile telephony, the Internet of things and cell-broadcast and real-time information systems have improved the suitability of tools and unpredictability of risks (Houston et al. 2015, Laverdet et al. 2018, Poslad et al. 2015). Over time, many countries have developed effective national warnings systems using these technologies (ETSI 2010). However, changes seem to be driven by political choices, by pitfalls observed after major events or following the failure of certain tools. This raises the question: do alerting tools change the way organisations operate or does the evolution of organisations require changes in the system?

To answer this, existing national alert systems of 5 countries (Australia, Belgium, France, Indonesia and the USA) were analysed by using methods derived from the contingency theory (Burns & Stalker 1969). We focused on ‘what’, ‘when’, ‘how’, ‘for what’ and ‘how to evolve’ questions and postulate that:

- national alerting systems depend on the structure and inherited governance more than on social and cultural characteristics of people or the nature of risks

- technological improvements in warning systems are leading to their mutation as some countries appear more advanced than others in the use of new warning technologies (i.e. cell-broadcast in the USA since 2006, social networks in Indonesia since 2011).

Considering this, this paper presents the characteristic elements of alerting systems in selected countries, presents the issues and an analysis, describes the main results and discusses improvements to alerts in France, where transition to digital alerting transition has been delayed.

Method

Five countries with strong differences

This analysis focused on 5 countries that have implemented, or are in the process of implementing, a Location-Based Alerting System (LBAS) (see Table 1). Location-Based SMS (LB-SMS) and cell-broadcast are 2 alerting systems commonly used at national scales. Three countries already use a LBAS (USA since 2006, Australia since 2013 and Belgium since 2017) and 2 others (France and Indonesia) do not yet have LBAS at the national level (although localised uses of these tools are possible).

Table 1: Main characteristics of the 5 selected study countries.

| Country | Number of inhabitants (millions) | HDI1 | Name of the national alerting system | Main alerting tool | Number of natural disasters (1970–2020)2 | Number of deaths (1970–2020)2 |

| Australia | 25.7 | 0.938 | Emergency Alert Australia | LB-SMS | 229 | 1,388 |

| Belgium | 11.5 | 0.919 | Be-Alert | LB-SMS | 58 | 3,295 |

| France | 66.9 | 0.891 | SAIP3 | Siren | 164 | 26,590 |

| Indonesia | 269.8 | 0.689 | Indonesian Warning System | Many used | 496 | 200,474 |

| USA | 331.8 | 0.920 | IPAWS4 | Cell-broadcast | 893 | 17,003 |

1 HDI (Human Development Index)

2 EM-DAT database (www.emdat.be/)

3 SAIP: Population Alert and Information System

4 IPAWS: Integrating Public Alert and Warning System

These 5 countries are of interest for other reasons. Australia has a federalised alerting structure, which makes it possible to adapt the alert to the characteristics of each Australian state and territory. Belgium abandoned its siren network in 2016 to replace it with LB-SMS, while centralising several digital alert tools within a single platform (Be-Alert). France is modernising its siren network. However, attempts to switch alerts by LBAS have failed due to the abandonment of the SAIP (Population Alert and Information System) application and the lack of agreement with operators to acquire LB-SMS or cell-broadcast since 2010 (Vogel 2017). The SAIP application was abandoned following dysfunctions (excessively long delays during the Nice bombing in 2016, and sending of false alerts in 2016 and 2017) and a lack of awareness of the tool by the population. But a 2018 European decree now requires all Europe members to set up a LBAS by June 2022. Indonesia is a multicultural country where the use of social platforms (like Twitter and Whatsapp) has become widespread. As early as 2006, the USA set up a multi-channel platform using the Common Alerting Protocol1 that integrates wide variety of organisations to disseminate alerts. The USA has also used cell-broadcast since 2012 and tests indicate good performance (Bopp & Douvinet 2020).

Table 2: Selected national reports used in this study.

| Selected country | Scientific literature | Technical report |

| Australia | Dufty 2014 | Vivier et al. 2019, AIDR 2019 |

| Belgium | Vivier et al. 2019, IBZ 2017 | |

| France | Douvinet et al. 2017, Bopp & Douvinet 2020, Douvinet 2018 | Ministère de l’Intérieur 2013, Vogel 2017 |

| Indonesia | Ai et al. 2016, Lavigne et al. 2010, Carley et al. 2016, Anggunia & Kumaralalita 2014 | AHA Center 2019 |

| USA | Bean et al. 2016, Bean 2019 | Vivier et al. 2019, FEMA 2018 |

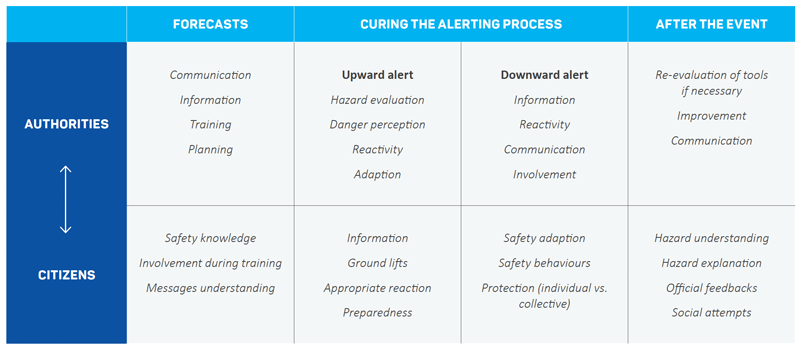

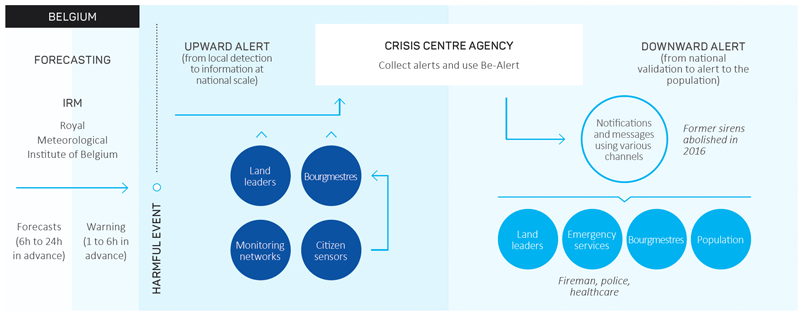

Figure 1: Overview of the organisations involved in the Public Warning System (Douvinet et al. 2020).

Qualitative survey based on contingency theory

An initial bibliography was compiled for each of the countries selected. Few scientific works have focused on the analysis of national alerting systems (Rogers & Tsirkunov 2011, Sorensen 2000) and the bibliography therefore focused on the many national reports and feedback following disasters (Table 2). This literature review highlighted a possible contingent aspect of alerting systems. Contingency theory states that systems must be adapted to their environment in order to be effective (Donaldson 2001). Previous work has shown that crisis organisations are contingent on their political, economic, social and natural environments (Jarman & Kouzmin 1994, Rosenthal & Kouzmin 1997). But what about organisational aspects, that is, procedures, type and number of actors authorised to disseminate the alert, hazard-detection modes, communications modes and interactions with tools? In order to answer this and to test the hypotheses, semi-directive interviews (N=35) with operational crisis managers in the 5 countries were conducted using an interview guide created around four topics:

- The organisational objectives of alerting: What are the objectives of the alert? In which temporalities? What place is given to the interpretation and decision-making?

- The structure of the organisations: Who receives the upward information? Who disseminates the alert? Who are the stakeholders involved?

- The techniques used: What are the means for hazards detection? What are the communications tools and the means for alerting?

- The operational culture: What are the values, beliefs, behavioural norms, lifestyles, symbols, etc.? How do they impact on choices and strategies?

Table 3 details the functions and the organisations of the participants interviewed for this study.

Table 3: List of institutions and services (without the name of people interviewed).

| Country | Function |

| Belgium | Head of Crisis Management Task Force, Belgium |

| Project Manager, BE-ALERT | |

| Australia | Zefonar Advisory, specialist in the design of requirement-led multi-purpose Public Warning System |

| Chief of Staff, Director, Operations Support, Australasian Fire and Emergency Service Authorities Council | |

| Manager, Emergency Management Community Information | |

| Public Information and Warnings, State Emergency Service, Victoria | |

| Deputy Chief Officer, Country Fire Authority, Victoria | |

| Project Manager, Disaster Mitigation, Bureau of Meteorology | |

| Assistant Commissioner, Victoria Police | |

| Manager Consultant in Solution / Everbridge | |

| USA | Professor, University of California, Berkeley |

| PhD (with former experience in risk forecasting in Brazil) | |

| Assistant Fire Director, US Forest Service | |

| Fire Chief, Sacramento Fire Department | |

| Deputy Fire Chief, Santa Rosa Fire Department | |

| Deputy Chief, California Office of Emergency Service | |

| Indonesia | Professor of Geology, Universitas Gadjah Mada |

| Psychologist, Institute for Community Behavioral Change | |

| Merapi Forecast, Center for Volcanology and Geological Hazard Mitigation | |

| Primary Planner, Regional Development | |

| Junior Planner, BMKG (Meteorology, Climatology, and Geophysical Agency) | |

| Vice-President, BMKG | |

| Researcher, Christian University of Jakarta | |

| Director for disadvantaged areas, BAPPENAS (Ministry of National Development Planning of Indonesia) | |

| France | Interministerial Chief of Staff for the South-West |

| Association of French Departments | |

| Deputy Director, Association of French Mayors | |

| Digital Department for Public Safety | |

| Liaison Officer for the Tour de France, Civil Security and Crisis Management Directorate | |

| Security and Safety Department Manager, Avignon University | |

| Security Manager, Orange Vélodrome Stadium | |

| Prefect, Hérault Department (former director of Civil Security and Crisis Management Directorate) | |

| Director, SDIS-13, President of the National Federation of French Fire Fighters | |

| Prefect, Seine-Maritime Department |

Results

Similar organisational objectives

The purpose of alerts is to warn as many people as possible of the arrival of a threat or a danger so that they can take appropriate protective action. The alert must be context-specific and adjusted to the evolution of the situation (during forecasting, a few hours before impact but also during the upward and downward process and after the event). The main objective is to minimise human and economic losses (Figure 1). From the point of view of the authorities, individuals must be receptive to the signals given in order to apply the instructions. The panic effects of crowds are a challenge to authorities although they are misrepresented in the literature (Weiss, Girandola & Colbeau-Justin 2011, Douvinet 2020). The objectives are achieved when institutions are prepared (through exercises) and citizens are informed of the risks, which is not always the case depending on the territory. Two visions of the alerting process therefore coexist: a binary approach (as in France, Indonesia and Belgium) or a gradual approach (USA and Australia).

Structural differences related to socio-political organisations

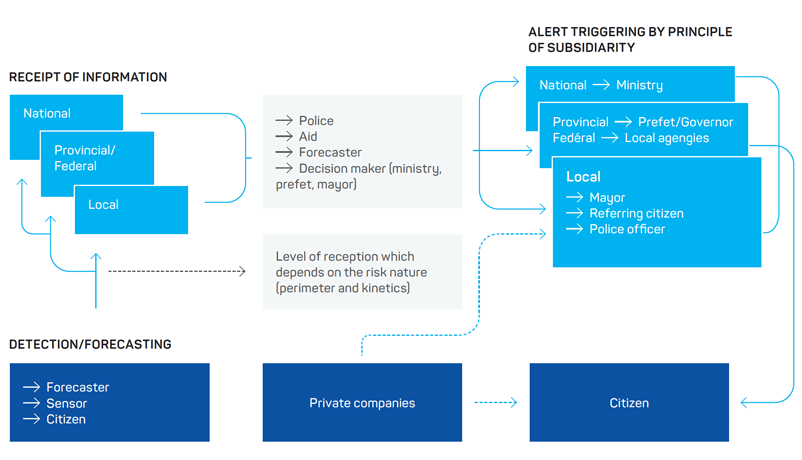

A pyramid-like structure is commonly observed that integrates 3 components (see Figure 2): the forecasters (i.e. the ‘experts’), the authorities (decision-makers) and the population (people to be protected). The subsidiarity of the alert was common to all the studied countries, except in Indonesia where the treatment of a crises is regional. The differences between federal (USA, Australia, Belgium) and unitary (France, Indonesia) states are secondary, in that, when there is a specific organisation responsible for warnings at the federal level (i.e. for structuring and for specific modes of communication), it is accompanied by harmonisation at the national level. In addition, in federal states, the actors involved in warnings are globally better interconnected than are those in unitary states. For example, incident controllers in Australia and police officers in Belgium are responsible for disseminating alerts. While Indonesia uses automated systems, decision-making remains essentially political and community leaders play a key role at the local level.

Figure 2: A recurrent pyramid-like structure exists in the studied countries.

Major disasters generally serve as a trigger in the evolution of national warning systems. Crises set the pace for the evolution of alert systems rather than the implementation of new high-performance alert tools.

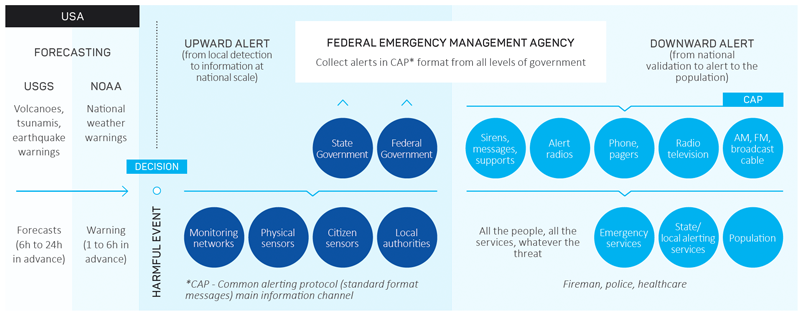

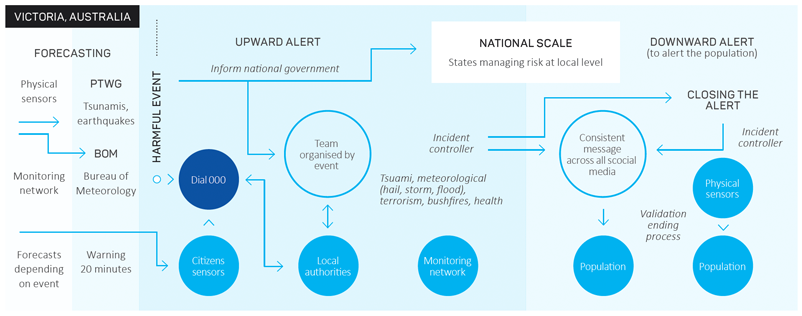

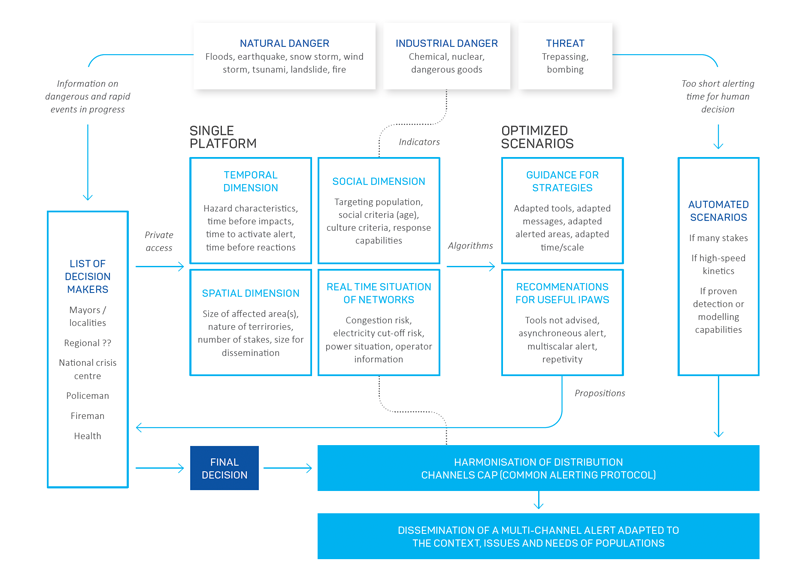

Tools are not always integrated in a multi-channel platform

From a technological point of view, multi-channel logic is favoured and needs to be encouraged. But each country is not similarly advanced on this point. This doctrine is advanced in the USA (Figure 3), in Australia (Figure 4) and in Belgium (Figure 5). The choice of dissemination tools depends on the nature of the crisis and on the estimated consequences, but all are integrated in a single approach. In Belgium, the LB-SMS is used by mayors for localised and adaptive alerts, as in Australia. In the 2 other studied countries, there is a greater disparity of tools and a lack of coherence between them. France has a large private sector participation in the field of alert systems. In Indonesia, there is a great disparity in access to alerts between inhabitants depending on their place of residence and their means of access to means of communication and social networks.

Figure 3: Multi-channel logic in USA with the Integrating Public Alert and Warning System infrastructure.

Figure 4: Multi-channel logic in Australia.

Figure 5: Multi-channel logic in Belgium with BE-Alert.

Pitfalls and drawbacks on human factor

Unsurprisingly, individual perceptions and, more broadly, human factors are difficult to take into account in every alerting system. Survey participants noted the difficulties in reporting information and the difficulties in trusting people to report this information. The contribution of community managers is in its infancy (in France) and is unevenly structured (in Australia and Belgium). In Indonesia, its cultural context makes it possible to use community leaders to improve the acceptability of alert messages, but the overwhelming power of these leaders can lead them to not follow warning recommendations. Exercises with communities are being used in Belgium and Australia. Many interlocutors recognise that certain categories of people remain excluded from alerts (due to disability, age and language barriers), although Australia is better recognising vulnerable or previously excluded sectors of communities for inclusion in emergency planning.

Discussion

This study showed that if organisational objectives are identical overall, the actors involved in issuing alerts do not have the same frame of reference or the same approach. The methods used are influenced by the national context and the crises that have occurred in the past, which have contributed either to the transformation or the improvement of the national warning system. More actors are becoming aware of community involvement during crises. But alerts are still too vertical and standardised to really empower local communities, despite the use of tools that could enable it. Although a vertical approach in terms of warning systems is challenged, the pyramid approach remains predominant (especially in France). Moreover, believing that warning tools can be ‘non-political’ (like the procedure itself) is a myth. Firstly, government advocates for warning systems to justify the funding allocated to them (Matveeva 2006) and often use them as a ‘good excuse’ (‘We did the best we could’). However, it is not because the tools are available that they are used. This observation, made in the early 2000s (Sorensen 2000), is still relevant today. The multi-channel doctrine has proved its effectiveness and could be better organised by defining a common alert protocol and using secure web-based platforms.

Three principles must be observed to guarantee an effective warning system:

Be consistent in the broadcasting of signals and do not leave any ‘gray areas’.

Have the weak signals announcing danger confirmed by the authorities or relevant organisations to provide accurate, complete and honest information without making assumptions,

Use common references to better engage with communities (Matveeva 2006, Stokoe 2016, Kuligowski 2014).

Creating dedicated and secure web-based platforms requires strong advertising. We could thus envisage a greater accountability of private operators through a delegation of public service associated with the telecommunications 5G network. Similarly, industrial operators or those in charge of a sensitive infrastructure, must be better integrated and made responsible. Nevertheless, a major stake in future warnings will be to take into account the contribution of citizens. Better detection of weak signals on digital social networks, including via artificial intelligence, is an important step. At the local level, the setting up of local watchmen (citizen sensor), perpetuated by repeated exercises, will allow the involvement of communities and the visibility of their actions (Figure 6).

The national warning system in France is representative of the gap that exists between the technical, social and organisational dimensions of alerting systems. In response to the Directive (Eu) 2018/1972 of the European Parliament2 of 11 December 2018 that established a European electronic communications code, France announced in September 2020 the implementation of a new alert system to be gradually deployed from 2021. The FR-Alert platform is a consequent evolution of old sirens systems made obsolete by urban development. It will combine cell-broadcast and location-based SMS technologies, thus being a hybridisation of systems used in other countries.

Figure 6: The way to go for creating efficient alerting national systems.

This technological leap should not hide remaining gaps. Technological fetishism led, for example, to the abandonment in 2018 of the SAIP (Population Information and Alert System) application set up by the French Ministry of the Interior. This technically robust application had failed to take into account the dimensions of use and was not as successful as expected. However, other technical devices exist and are well suited to end users, for example ‘kidnap alert’ (inspired by the Amber Alert system set up in the USA in 1996) or motorway warning systems that combine technical and social dimensions. The technical aspects are only one part of the problem. Indeed, one may wonder about the efficiency of a system that could send thousands of messages in a few seconds if it is not adapted to the kinetics of the event or if it is not understood by those who receive it or if it takes hours for the authorities to make the decision to alert. France has made a bold choice, but the decision-making process, based on control-and-hierarchical command, raises questions about the real capacity to alert communities in good time. The lack of a long-term vision or political courage may prevent organisational changes.

Conclusion

None of the 5 countries studied has established a real upward alert platform and we consider that they have not yet completed a digital transition of their alert systems. This is, however, a major lever for the future. This study showed that a very hazard-centred approach to systems continues to persist. We note that contingency theory only partially explains the form and functioning of the national warning system. Two visions are opposed: on one hand there is no differentiation between the tools used to disseminate information according to the hazard; on the other hand, only the message must vary and be adapted. A third way seems relevant, which is the possibility of adapting the dissemination tool to the hazard type.

The 4 stages of this technological transition can be summarised:

- Step 1: Better crisis prevention. Modernisation of hazard measurement tools, priority given to sensor networks.

- Step 2: Internal reorganisation of the system, adaptation to the data from the (rapidly arriving) sensors. Reorganisation of communication modes. Start of communication on digital social networks. Use of a LBAS sparingly.

- Step 3: Official and national use of a LBAS.

- Step 4: Ability to receive upward citizen alerts.

A recurring aspect is the evolution of systems in response to major disaster events. These disasters reveal the limitations of traditional warning systems, leading countries to reform their warning systems and equip themselves with more powerful tools. This, in turn, conditions hazard-centred systems rather than people-centred ones (Gaillard et al. 2010). The race for technological innovation must not boil down to a race for technical performance but must, on the contrary, put the individual back at the heart of the system. Warnings and alerting can only be approached in a global way, with a multidisciplinary view, an inter-ministerial position and which places the end user, the citizen, at the heart of the system.