Enhancing community resilience: what emergency management can learn from Vanilla Ice

Dan Neely

Dan Neely, Manager, Community Resilience, Wellington Region Emergency Management Office, shares the practical ways community resilience is being built in New Zealand.

Article

This paper is based on a presentation given at the EMPA NZ Conference (Auckland) in May 2014.

It might seem odd to think that Vanilla Ice should act as a guidepost for the future of the emergency management sector, but stay with me, and I’ll do my best to explain how Ice Ice Baby1 has become a mantra in Wellington.

Nearly three years ago, the nine local councils throughout the Wellington Region were amalgamated to form the Wellington Region Emergency Management Office (WREMO). The goal was to adopt a singular approach across the region as well as rethink how emergency management is practiced in our communities. This directive gave the new Regional Manager, Bruce Pepperell, the mandate to explore non-traditional organisational models and methodologies. With the Christchurch earthquakes fresh in our minds, ‘community resilience’ became a particular area of focus for the new WREMO, with one-third of the organisation’s resources dedicated to delivering resilience outcomes.

Resilience is, quite possibly, the buzzword of the decade and much nuanced discussion has been made regarding what a resilient community looks like. Unfortunately for practitioners, there are few guideposts that outline how to operationalise resilience and what our role should be in that process. The Christchurch earthquakes of 2010 and 2011 reframed the sector’s understanding of just how amazingly capable and innovative the public is during response and recovery. The challenge for emergency managers is how to harness that energy to help build stronger, more connected and prepared communities. One of the keys to unlocking this challenge is to help communities function well every day, not just during and after an emergency event.

Build capacity, increase connectedness and foster co-operation

In 2013 the editor of TIME magazine wrote, ‘we are living through the most immense transfer of power from institutions to individuals in history’ (Sept 30, 2013). This decentralisation of power is occurring across the world in the forms of Wikileaks, citizen journalism via Twitter, and the spontaneous formation of groups like the Student Volunteer Army that largely shaped the Christchurch response. The internet and mobile phone are empowering individuals to organise themselves in ways unimaginable in the recent past. As one of the institutions of power, emergency management needs to embrace this shift and recognise it as an opportunity to create meaningful partnerships with our community leaders across all phases of emergency management.

Relationships matter. There is a significant body of research that highlights the important role of social relationships in response and recovery. Just as our everyday lives rely on the support of family, friends and wider acquaintances, these established relationships are often the best resource during and after an emergency event.

For the new Community Resilience team, the first step was to move past ‘public awareness’ and ‘survival’ towards increasing the connectedness of communities and enabling people to feel empowered to manage their households and neighbourhoods in the event of an emergency. We needed to move from promoting can openers to promoting co-operation. The team wanted to work with community leaders in more collaborative ways, become facilitators of their ideas and help them create pathways to connect with each other, and us. Finally, we wanted to create a system that linked the informal community response and recovery to the formal government one. To achieve this, we had to step away from the command-and-control comfort zone towards something more akin to community development. This required a re-examination of what we thought we knew and resulted in some upskilling of the team with training in facilitation, storytelling, Design Thinking, and marketing. Most importantly, we had to learn to listen better to communities and partners. If we are going to create an environment that empowers others to be more connected and prepared, we must really understand their diverse interests and needs. If command-and-control is the appropriate model for response, then communicate-and-collaborate has become WREMO’s complementary model for enhancing community resilience. It is an organisational structure that is more akin to a plate of spaghetti where relationships intertwine and overlap, instead of connecting through a defined structure like an incident command system. This ‘messy’ connectedness approach aligns with WREMO’s goal of being a ‘network enabled’ organisation, whereby a small team is leveraging off the efforts of others as well as the benefits of modern technology.

Stop. Collaborate and listen

Setting aside the artistic merits of Ice Ice Baby, the song’s opening line provides sufficient guidance for practitioners to begin effectively engaging with communities. By adopting a communicate-and-collaborate mindset, we cease doing things to communities and approach our work with them as partners.

Community Resilience Strategy. At: www.getprepared.org.nz/publications.

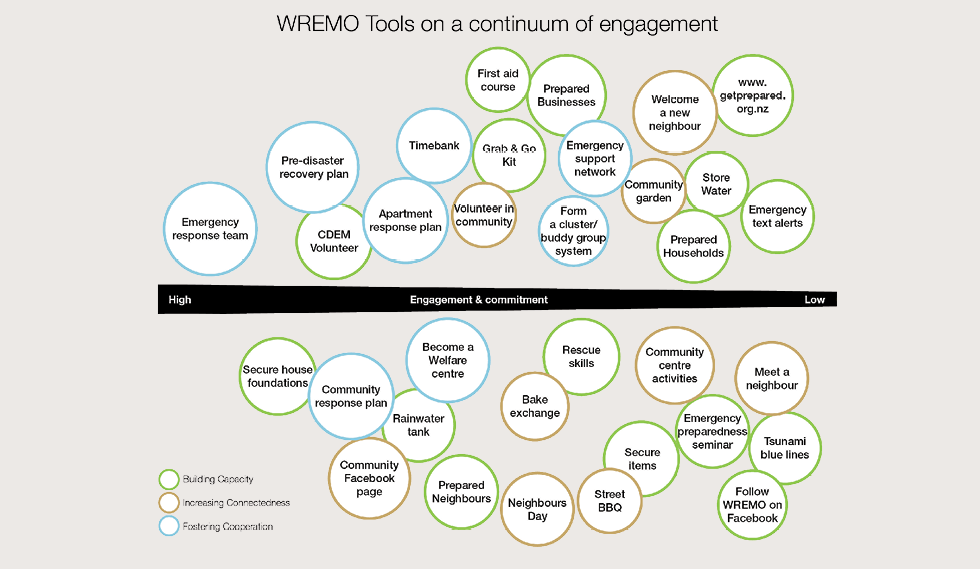

To help guide our resilience compass north, the team developed a Community Resilience Strategy that provides a set of engagement principles, such as ‘listen first’ and ‘focus on local solutions’, as well as a range of tools for individuals and organisations to get involved in ways that are appropriate for them, not us. Instead of educating everyone to achieve ‘Rambo Level 5’ preparedness, the approach has focussed on developing a wide range of tools that cater to diverse interests and levels of commitment. For the less enthusiastic, minimal engagement might be through a painted blue tsunami marker line on the road or nothing more than following WREMOnz on Facebook. For those who have greater interest or time, completing a CDEM volunteer training program or participating in the creation of community response plans helps build capacity and foster co-operation. A Continuum of Engagement model presented in Figure 1 provides an example of how these tools are represented by a person’s level of interest.

Figure 1: Model of Community-Driven Emergency Management.

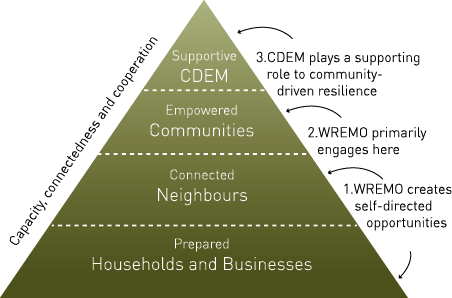

To implement this communicate-and-collaborate model, each team member is given a geographical area of responsibility with a staff-to-resident ratio of roughly 1:75 000. When viewed from this perspective, the large connectedness challenges are obvious, which is why, philosophically, we have moved away from presenting to classrooms of children, onto meeting with school principals to implement school-wide response and education plans. This approach begins by building capacity, increasing connectedness and fostering co-operation with householders and businesses as the foundation of connectedness, represented by the System of Community-Driven Emergency Management shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: WREMO tools on a continuum of engagement.

Building on this foundation the next level emphasises the relationships of neighbours, which is our number one preparedness resource promoted before, during and after an emergency. The majority of tools developed for these two groups, such as the It’s Easy suite of emergency preparedness guides, can be applied without the guidance or support from an Emergency Management Advisor.

The third level illustrates the focus on working with local leaders to bring about change within their networks. Some of the drivers of change include school principals, managers of social agencies, and locally elected community members. Finally, representing the least amount of space in this model is the overarching role of a ‘supportive CDEM’. This is a change of mindset for our organisation and reflects how we have evolved to seeing our community as partners.

Armed with this diverse set of tools (and a razor thin budget), each member of the team is embedding themselves into their defined geographical areas. They are seeking out community leaders, listening to what matters to them, and helping with initiatives that increase their area’s connectedness and preparedness. Another way we are achieving this is by allocating ten per cent of the team’s time to support community organisations in ways that have little or nothing to do with emergency management. This might take the form of spending a couple hours just getting to know the people in their environment or providing hands-on assistance at a community event. All of these inputs lead to the enhanced resilience of our region, whether it be in preparing for an inevitable large earthquake or managing the stressors of life’s day-to-day challenges.

Community resilience tools

Tsunami Blue Lines

Capturing the public’s attention and motivating them to act is one of the biggest challenges facing planners and communicators. A pilot community was established to look at the use of tsunami signage in Wellington. The community could choose between traditional signage and ‘something else’ they could design. Community members jumped at the opportunity to create their own solution, which they did by painting big blue lines on roads to mark the maximum run-up height of a tsunami. The impact and buzz around the concept has been remarkable and independent researchers have found it has raised tsunami awareness by both locals and visitors. This innovative approach was made possible by creating the ‘white space’ for communities to consider and design their own solutions. The result was powerful and cost-effective solution that would never have been considered within the office environment.

CDEM volunteer training

The CDEM volunteer program teaches community members how to promote preparedness in two-minute conversations within their own networks (without sounding like fanatics), provides assistance to the official CDEM response, and supports their community after a large disaster. We no longer maintain a team format, we do not require a time commitment, we do not issue NZ Unit Standards nor teach CIMS. Instead, the CDEM volunteer training involves teaching large numbers of people the basics of emergency

co-ordination and how to provide comfort in an emergency so that a community response is more effective and efficient from the outset. We have experienced a huge surge of interest since revamping this program because the approach supports a way for anyone to get involved and contribute.

Image: WREMO

Community members are encouraged to promote preparedness in their local areas.

Preparedness enablers

To make preparedness products affordable and fit-for-purpose, we worked with private suppliers to create preparedness enablers that sell for half the price of similar products on the market. Examples include the Grab & Go Emergency Kit and the 200L Emergency Rainwater Tank. These products have been hugely popular and have helped householders and businesses make tangible improvements in preparedness. Creating ways to leverage off the private sector is the future for our team.

Social media

Increasingly, emergency management planners recognise the value of using social media to push messages and gather information during a response. Although it might seem counterintuitive, the WREMO team seldom posts emergency preparedness messages on its Facebook page. Instead, posts are generally about community events and ideas that bring people together. The guideline is that social media postings must be interesting to followers and somehow lead to stronger communities. Of course during an emergency posts are relevant and provide information for the public. This community approach has enabled Facebook/WREMOnz to build trusted relationships with its users and has fostered one of the largest followings for an emergency management office in the world with more than eight per cent of our public following the page.

Community-driven response plans

Ideally, communities should be able to look after themselves without the assistance of emergency services for the first few days after a disaster. We are helping to achieve this by bringing together leaders and managers of large resources within communities to meet each other, often for the first time, to work together to determine how they would address a set of common challenges following a devastating earthquake. Each plan is enabled by a Memorandum of Understanding with the local council to support and fund a community-driven response. This simple act goes a long way to build trust between community leaders and local government. The goal is to keep the working groups together by facilitating their collaboration and ideas on other projects that ‘make their community even more awesome’.

We’re learning as we go and we need your help

The approach to community resilience is an ongoing and adaptive process based on research, existing good practices in community development, and the willingness to trial and make errors. We are doing the best we can by our communities and in many respects, learning as we go. WREMO is working with other practitioners in the region and across the country such as our local councils, NZ Red Cross, and Marae. We are collaborating with leading international practitioners such as Daniel Homsey from the City of San Francisco Neighbourhood Empowerment Network and researchers like David Johnston and the team at NZ’s Massey University Joint Centre for Disaster research. In a shared initiative, the Community Resilience Strategy has become the foundation document for an International Centre of Excellence in Community Resilience (ICoE:CR) through the Integrated Research on Disaster Risk, a program within the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. The goal of the Centre is to bring researchers and practitioners together to help answer the question, ‘how does a community make itself resilient to future disasters?’

The Resilience Toolbox

Enhancing community resilience is a challenge many cities around the world are actively exploring. We are asking for your help to advance the practice of community resilience by sharing your work and research with us at www.resiliencetoolbox.org. Through the ICoE:CR, we have developed the Resilience Toolbox as an online knowledge-sharing bank of tools and practical research that helps answer the ‘how’ question. All of WREMO’s tools, as well as a growing list of partner resources, are freely available online.

Taking a cue from Vanilla Ice: the more we collaborate and listen to one another, the more our communities will benefit.

About WREMO

The Wellington Region Emergency Management Office is a semi-autonomous organisation that co-ordinates civil defence and emergency management services on behalf of the nine councils in the Wellington region in New Zealand.

Website: www.getprepared.org.nz

Email: wremo@gw.govt.nz

Facebook: www.facebook.com/WREMOnz

1 Ice Ice Baby is the title of a song by artist, Vanilla Ice, from the 1989 album ‘Hooked’.