This article proposes a working definition for the term ‘lost wilderness tourist’ and uses this definition to examine lost wilderness tourist events through the lenses of tourism literature, lost person behaviour literature, search and rescue literature and wilderness tourists in Australia. A tool was developed using existing literature to recruit self-identifying lost wilderness tourists. First-person stories were collected through open ended, one-on-one qualitative interviews. Interview data were analysed using 3-step coding. The findings propose a definition for the term ‘lost wilderness tourist’, establish that lost wilderness tourist events can be categorised as ‘disorientated’ or ‘stuck’ and that these 2 meta categories can be further divided into subcategories. The findings offer insights into the lived experiences of lost wilderness tourists. These insights are useful for anyone with an interest in lost wilderness events and the safety of people in Australia’s wilderness areas.

Introduction

The Australian landmass covers approximately 7.6 million square kilometres and includes deserts, savannahs, rainforests, mountains and alpine regions (Australian Maritime Safety Authority 2021). Each year, approximately one and a half million people enter Australian wilderness spaces in pursuit of leisure or pleasure (Cohen 1979, Leiper 1979, McCabe 2005, Yu et al. 2012). Several thousand of these people become lost (Dacey, Whitsed & Gonzalez 2022).

The benefits of wilderness tourism are well documented and include spiritual, physical and mental health benefits (Boller et al. 2010, Boore & Bock 2013). Tourists1 are however, vulnerable because of their tourist status (Faulkner 2001, Gurtner 2014, Jeuring & Becken 2013). Despite their unique wants, needs and vulnerabilities, wilderness tourists are not identified in contemporary lost person taxonomies. Lost person taxonomies have been developed by Koester (2008b), Twardy, Koester and Gatt (2006), the Australian Maritime Safety Authority (2021), Schwartz (2022) and Whitehead (2015). These taxonomies are based on statistical data that connects found locations, demographics, psychographics and behavioural patterns (Australian Maritime Safety Authority 2021, Koester 2008b et al. 2016). However, the current body of work lacks consistency and the depth that is required to address the unique needs of lost wilderness tourists. This paper uses qualitative analysis to ask who a lost Australian wilderness tourist is and what constitutes a lost wilderness tourist event.

These questions are answered by positioning tourists within lost person literature, developing a working definition for the term ‘lost wilderness tourist’ and using that definition to categorise lost wilderness tourists. This provides a baseline understanding of lost tourists and provides a tool for further lost wilderness tourist research.

Theoretical overview

Literature review

Tourists are voluntary, temporary travellers making discretionary trips outside of their usual environments to engage in touristic behaviour in pursuit of leisure or pleasure (Cohen 1979, Leiper 1979, McCabe 2005, Yu et al. 2012). They either self-identify as tourists or are easily identified by others as tourists (Yu et al. 2012).

Lost people theorists such as Schwartz (2022), Montello (2020), Fernández Velasco and Casati (2020), Dudchenko (2010), Hill (1998, 2010) and Syrotuck and Syrotuck (2000) show that lost people may be unable to find their way, may be injured or incapacitated, may be unable to be found, may be unable to understand or to cope with the situation, may be deceased, may be thought of by others as lost or may be experiencing a combination of these predicaments. Fernández Velasco and Casati (2020) also suggest that being lost has both subjective and objective elements as lost people negotiate the objective reality of being lost and the subjective feeling of disorientation.

By merging tourism, social science, lost person behaviour and search and rescue literature Schwartz (2022) defined lost wilderness tourists as:

…people who engage in touristic behaviours in wilderness environments and are identified by themselves or others as tourists who are geographically disorientated and / or unable to return to places of safe refuge. (p.64)

This definition is used to develop the research method for this paper as it seeks to answer the question ‘who is a lost Australian wilderness tourist?’.

Method

Tourists regularly become lost in wilderness environments (Boore & Bock 2013, Goodrich et al. 2008, Scott & Scott 2008, Twardy et al. 2006). This study examined who lost wilderness tourists are and explored what constitutes a lost wilderness tourist experience. It steps away from the searcher-centric quantitative methodologies of existing taxonomies such as those developed by Koester (2008b), Twardy et al. (2006) and the Australian Maritime Safety Authority (2021) and takes a qualitative, lost-person centred approach. Sampling, data collection and data analysis is consistent with generally accepted qualitative research design, methods and methodologies as prescribed by Maxwell (2005) and Neuman (2014).

Participant recruitment

Recruitment of participants was via online and other channels such as word of mouth, print media, radio advertising, and snowballing to target people who had been lost in the wilderness while engaging in recreational or touristic activities. Self-identifying candidates were asked to contact the researcher through email, telephone or, a third-party contact. Potential candidates were screened for eligibility and suitability. Candidates who were deemed suitable were offered places in the study. Targeted advertising and self-selection ensured a high conversion rate between the people who connected with the study and those who participated. One candidate was excluded because they became lost while working. One candidate self-excluded because they felt that participating could become traumatic. The recruitment process resulted in 14 suitable candidates to be interviewed for this study.

Data analysis

Data was collected via one-on-one interviews. Interviews were electronically recorded and transcribed and coded using a 3-step process. Initial coding identified emergent themes. Axial coding clustered the open codes into meta-level themes and selective coding was used to identify key narratives. Ethical considerations were addressed through the James Cook University Human Research Ethics Committee (ethics approval number H8401).

Screening questions

Each participant was screened for age and to ensure they had been a lost wilderness tourist in Australia.

Question 1. Is the person over 18 years of age?

Question 2. Did the experience occur whilst engaging in touristic or recreational activity?

Question 3. Did the lost experience happen in an Australian wilderness area?

If the answer to all these questions was yes they were asked four further qualifying questions.

Question 4. Did they know their geographic location?

Question 5. Did they know where their intended destination was?

Question 6. Could they get to their intended destination unaided?

Question 7. Did someone else believe they were lost?

If a participant answered ‘no’ to any of questions 4, 5 or 6 or ‘yes’ to question 7, they were invited to continue in the study. Candidates were given study information and asked to provide informed consent. All participants were assigned pseudonyms that are used throughout this paper.

Findings

Overview

Participants included males and females ranging in age from early 20s to mid-70s. All identified as Australians and all had some prior wilderness experience. All had entered wilderness areas on foot and all were motivated by recreational goals such as hiking, photography and exploring. Some had travelled considerable distances to reach their wilderness destination.

Lost events occurred in various environments including rainforests, mountains, alpine regions, savannahs and outback regions. Most events occurred on the Australian mainland; one took place in Tasmania and one occurred on a subtropical island approximately 700km off the Australian east coast. Participants were considered lost because they self-identified as lost, were considered lost by other people or both self-identified as lost and were also thought of as lost by others. Lost events could be broadly categorised into those involving disorientation and those involving entrapment.

Geographically disorientated

Participants who identified as geographically disorientated were those unsure about their location, their destination or their route. Some were completely lost, some were partially lost and some became lost, unlost and then re-lost. Some participants became disorientated after failing to navigate tracks, some became disorientated while attempting to navigate off-track and some were unable to navigate between known locations. The most common scenario for participants who were geographically disorientated was that they were partially or temporarily disorientated.

Partially disorientated while on-track

Some participants became disorientated while they were following a formed and marked track. Bruce, for example, became disorientated while on the Overland Track2 because of unexpected foul weather.

We were about halfway up the mountain when it started sleeting. We thought, oh the weather will be fine- like it'd be okay; we're like we're all geared up for it. And the further we got up, the harder the wind got, the icier things got, the snow started or the sleet turned into little cubes of ice. We had trail markers; we weren't necessarily lost. But we also didn't know just how far because I hadn't been on that trail. We knew that we had to get to Kitchen Hut at one point on the trail, but we had no idea how far along the trail we were…pure sheer anxiety and we’re in a really bad space.

[Bruce]

Partially disorientated while off-track

Some participants became disorientated while off a trail. These participants had planned to explore off-track and were comfortable doing so. Thomas became disorientated exploring a rainforest valley. Max became disorientated attempting to return from a mountain summit and Liz became disorientated trying to navigate off a mountain top. Liz described her experience:

Dad decided we would not approach Mt Ossa by the usual track. We would go up a different track and then walk out the easy track. The problem with that was that meant you would follow markers on trees and rocks and so on because there wasn't a defined trail. It wasn't as well marked as many other trails.

We managed to get up to the top. And, of course, there was a cairn there and there were footprints everywhere. And it was like ‘okay, which was the way down?’. And we couldn't find the trail marking down because most people approach from the trail knowing where to go back to. So there were too many footprints and if you followed some, it would lead to nothing.

So we were looking for a ridge and then the track should have been slightly to the side of it. And so unfortunately, there was another very prominent ridge running directly south which was not the ridge that we were meant to be on. So we searched everywhere along that ridge line and to the banks on each side of it. And it had been too many years since my dad had climbed Mt Ossa so he couldn't remember. So of course, we're looking down and everywhere we looked it was this huge boulder field. So these massive boulders took a lot of effort to climb up and over them. And so we looked, I don't know how many hours we were looking.

[Liz]

Unable to navigate between known locations

Some participants knew where they were and knew where they wanted to go but couldn’t navigate between known locations without becoming disorientated. This was especially common at the tops of mountains and peaks. These participants were unable to navigate to target destinations but could easily return to their known locations at the tops of hills or mountains. This was described by Dale talking about how he dealt with a panicked member in his walking party.

Two of the guys got into a panic state, so I tried to keep them from getting too panicky about the fact that, you know, we don't know where we are and everything. I’d say, ‘well we know where we are on top of this mountain we know exactly where we are we just can’t see where we're going’.

[Dale]

For Dale, factors that made it impossible to navigate included too many trails, poor weather and reduced visibility.

Once we got on top of the mountain that was a big problem; it was just tracks everywhere. And then a big weather front came through. And it just closed in over us and the visibility was about 2 metres in front of us. We had no idea exactly where we were.

[Dale]

Max also became stuck at the top of a hill. He described his disbelief at being unable to find the way down.

It was probably about 6 hours that we were lost. In fact, I don't even like to use the word lost because I knew exactly where I was. I just couldn't get out…I was feeling a bit scared at this stage. We continued going up and down for probably 2 hours, 3 hours. And I could not believe that we couldn't find our way back down because there was no trail, but it was simply just walked up. And well, how come we can't walk back down? Yeah, I mean, it's just [you] follow a ridge line. And to know you’re just going to a peak. Yeah. It was amazing that you can be so close and still not get out. You’re still lost. You still can't get down.

[Max]

Reorientation attempts

When participants realised they were disorientated they typically sought to reorientate themselves back to their original target destinations or to other known locations such as tracks, high points and roads. For some, these reorientation attempts were successful. One example was William.

I didn't realise the weather was a problem. And 3 or 4 hours later, after I'd been trying to get down and I got the break in the clouds, [I] climbed a tree and looked out and saw the islands off to the right. Not straight ahead. And that's when I realised that the clouds had confused me. Until then I didn't realise and perhaps I might have been able to get myself out of it.

[William]

An example of failing to reorientate was Mary. On the second day of her lost experience Mary found a marker and thought she had become reorientated. She then lost the track again.

And the next morning I got up and I found a marker. So I set off thinking, ‘oh, this is great’. You know, I'll be back. I knew I didn't walk very far…good I'm on my way back. I can't be very far I'm right. I still had a tin of sardines. And I wasn't worried about food. I think I still had a muesli bar. I was positive and somehow then I got lost again.

[Mary]

Completely disorientated

Participants who reported being completely disorientated included Mary (early 70s) and Carly (early 20s). Mary became disorientated because the trail she was following was poorly marked. Carly became disorientated because she followed the wrong creek bed. Mary was lost for 3 days and 2 nights before being spotted and rescued via helicopter. Carly was rescued via helicopter after she activated her personal locator beacon on the first day she was lost. Mary described becoming disorientated.

And after a bit you couldn't see any path on the ground. It wasn't discernible at all. It was rocky, it was open. But it was still, you know, a bit hilly and you were relying on metal posts with a triangle. And sometimes you couldn't see, you couldn't always see them in your line of sight. So you're heading thinking, ‘I think I'm going the right way’. And then I'd have to backtrack to the previous post. And that's how I got lost. I lost the posts.

[Mary]

Carly also described realising that she was disorientated.

I realised that afternoon that I was meant to be at a campsite at a certain time and that time had passed. And I was just happily travelling along a creek bed. And I looked at my map and realised that I'd actually meant to be going, I think, southeast and I was going northeast. And I had no idea how long I'd been going in the wrong direction for I had no idea kind of where I was. And I immediately panicked.

And like now looking back, I'm like ‘how did I select the wrong creek bed?’. But I was obviously just having a great time trotting along. There were markers. Yeah, I just missed the marker. I just missed the marker like… there's so many dry creek beds that are kind of going every which direction along that trail and I'd obviously been looking at something and missed it and just kept walking. And as I said, it was when I looked at the map that day, and I was like, ‘ I'm supposed to be going southeast, but I'm going northeast’. That's what I really realised. Like I've missed, I'm not in the place where I'm supposed to be today. And I'm not going the way that I meant to be going.

[Carly]

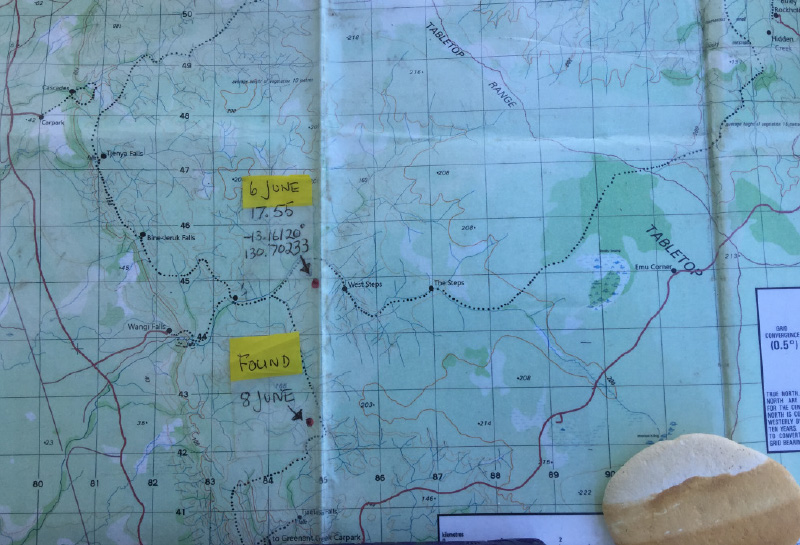

Map showing Mary’s location when lost.

Image: supplied (Mary)

Physically stuck

Physically stuck participants had become stuck because of external factors such as extreme weather or impenetrable terrain or because of internal factors such as injury, fatigue and skill deficiency. Some knew exactly where they were, some had some idea where they were and others were completely disorientated.

Entrapped

One participant who became entrapped was Bryan. Bryan had abseiled midway down a waterfall and became stuck on the rock face. After several self-rescue attempts, Bryan became fatigued and remained where he was until he was rescued via helicopter the following morning.

We decided to start climbing and I was having a lot of trouble. I was only getting a few metres and it was taking a long time to do it. He was sort of trying to show me, but we were just having trouble. Then we stopped for a while and then the next section I just free climbed up because that was easier for me; it’s exhausting but it’s easier. Then we got to the point where I stopped and that’s where I stayed. I waited for someone to go back up…right at the beginning I thought I would, it didn't look hard. You don’t realise it could be so much trouble.

[Bryan]

Stuck due to injury

Oscar became stuck after falling and injuring his foot.

So basically, it [the log] fell and it collapsed on my foot. And what I did is, yeah, I just looked around at everyone. And I said, ‘look’, I just laughed and I said, ‘we'll go to the summit, I'll put my boot on’. And straightaway I remember standing up and this enormous pain; I just went ‘this is so intense’. This is like, this absolutely sucks. And what I did is I literally stood up and then fell back down and then my foot just stayed in the water. And that's where I stayed for 2 and a half hours. I couldn't move.

[Oscar]

After the onset of a genuine fear for his survival, Oscar accepted he was stuck and called for help.

I just wanted to get back to the car because I knew the trip was over straightaway. And I just said, ‘maybe we'll come back in 3 weeks to do it again’. And I looked at everyone and I said, ‘look, we've got to call…we've got to call an ambulance, because what happens if a blood clots here? You know, like, what happens if there's a blood clot and I don't want to die’.

[Oscar]

Oscar became stuck in this creek after injuring his foot.

Image: supplied (Oscar)

The log that injured Oscar’s foot.

Image: supplied (Oscar)

Disorientated and stuck

Some participants were both disorientated and stuck. Thomas became disorientated in tropical rainforest, then became stuck in impassable terrain and then injured himself trying to self-rescue. Max and his companion became stuck after trying to navigate through harsh tropical vegetation.

And when we started to come back down, we got caught in this big wait a while thicket, that was the thickest infestation of wait a while I’ve ever seen in my life. And we're getting lacerated and so we went OK, this is stupid. We didn't come through this on the way up. So we just climbed back up, and it's quite steep at the top. Got to the very top, you can tell you’re at the top because it's only about the size of a small house. Then, so we thought okay, so we were just down there so let's just bear off a couple of degrees and we beared off a couple of degrees and we thought we'll go down here.

But anyway, so we beared off a few degrees and we went down again. Still wait a while forest. What the hell. So we went back up again. Beared off a bit more went down again, wait a while. So we thought okay, we must have been a bit this way. So we try the third time. And we came to the real cliff face… my head starting to go holy crap…And Bruce was cramping. We've run out of water. And he started to get a little panicky. So I was trying on the outside to be really calm, but inside I’m thinking how can we not find this trail?.... He got so exhausted and the cramps are so bad, he just had to sit, I made him just stop and just sit under a tree.

[Max]

Discussion

The objective of lost person research is to develop better understandings about how people become lost and what can happen in lost person events in order to plan for, prevent, respond to and recover from these events. Contemporary lost person behaviour research has tended to be searcher focused and quantitative in design. This approach has produced excellent predictive models such as those developed by Koester (2008a) and has undoubtedly saved many lives, but it may lack some of the richness and depth provided by qualitative studies.

This study has moved away from that approach by adopting a lost person focus, by using a qualitative research methodology and by looking beyond rescue literature as it has sought to define and categorise lost wilderness tourist events. This study used multi-disciplinary literature, first-person narratives and qualitative enquiry to ask who a lost Australian wilderness tourist is and what constitutes a lost wilderness tourist event. A literature-based definition provided a baseline for recruiting participants. Self-identified participants were screened against this literature-based definition and working definitions were developed.

All study participants had entered wilderness areas in pursuit of leisure or pleasure. They expected to engage in activities of their choosing, they expected to traverse their chosen paths and they expected to leave the wilderness areas at times and places of their choosing. This did not happen. Some participants became disorientated, some became stuck and some became both disorientated and stuck. Some participants self-rescued and some required external assistance. The study findings suggest that a lost wilderness tourist might be defined as:

…a person who has entered a wilderness area in the pursuit of leisure or pleasure and who has become permanently or temporarily unable to reach a place of safety because they are geographically disorientated, geographically stuck or both disorientated and stuck.

The study findings also resulted in 2 meta-level lost categories and 5 subcategories of lost wilderness tourists. The meta-level categories are ‘geographically disorientated’ and ‘physically stuck’. Participants who were disorientated could be further categorised into ‘partially disorientated’, ‘completely disorientated’ and ‘unable to navigate between known locations’. Participants who were physically stuck could be further categorised into those who were ‘impeded by internal restrictions’ and those who were ‘impeded by external restrictions’. This is summarised in Table 1.

Table 1: Geographic awareness of lost people.

| Fully aware | Somewhat aware | Not at all aware |

Knows:

|

Unsure of:

|

No awareness of:

|

| This person is not geographically lost. | This person is partially disorientated. | This person is completely lost. |

| This person may still be a lost person if they are immobile or entrapped. | This person may also be a lost person because they are immobile or entrapped. | This person may also be a lost person because they are immobile or entrapped. |

Limitations

A limitation of this study was the lack of international tourists. This was due to government-imposed travel restrictions associated with the pandemic response. A second limitation is that the study was informed by only 14 participants. This low sample rate is typical of qualitative research. All the participates provided valuable qualitative data that was used to develop the findings. Furthermore the participants experiences reflected most Australian landscapes including Tasmanian alps, northern rainforests and central Australian deserts.

Future research

The methodology, the findings and the conclusions of this study offer research opportunities. The proposed definition and taxonomies might be tested and refined. The qualitative, user-centric methodology might be used to further understand lost wilderness tourist experiences. The proposed methodology might also be used to better understand other groups of lost people such as people with disability and people with dementia. Future research might seek to compare, contrast and combine the richness of qualitative research with the high sample rates of quantitative research methods to develop understandings of lost person behaviour and guide lifesaving best practice. Future research should also seek to recruit international tourists who become lost to examine the similarities and differences between lost local tourists, lost domestic tourists and lost international tourists.

Conclusions

This paper achieved 3 outcomes. It positioned lost wilderness tourists inside lost person literature. It developed a working definition for the term ‘lost wilderness tourist’ and it used the proposed definition to categorise lost wilderness tourists.

Combining tourism literature, lost person behaviour literature and search and rescue literature with empirical research positions tourists inside lost tourist research. This produces findings that can be used by anyone including wilderness tourists, tourism agencies, response agencies, policy planners and academic theorists. Tourist-centric stakeholders could use the findings to better understand lost tourist journeys. Stakeholders with an interest in prevention could use the findings to develop risk reduction strategies to reduce the trauma of lost tourist events. Search and rescue stakeholders might seek to integrate the proposed lost wilderness tourist definition and categories into existing taxonomies to improve search outcomes.