Digital platforms have become valuable resources to citizens as they allow immediate access to quality information and news. Staying up to date with information and news is particularly vital in crises such as bushfires. The 2019–20 bushfire season in Australia was extreme, resulting in widespread devastation and loss of life, property and wildlife. Communicating with affected communities is a critical component of community response and resilience in a disaster. Organisations, such as ACT Emergency Services Agency and the NSW Rural Fire Service, need to provide timely, accurate and reliable information. This study investigated official communication using Facebook during the Orroral Valley bushfires from these two emergency services agencies and considers to what extent messaging demonstrated the characteristics of effective crisis communication, including application of the National Framework for Scaled Advice and Warnings to the Community. A content analysis of over 600 posts revealed marked differences in approaches. The study revealed the benefits of using a combination of text, images and infographics in communication activities. Suggestions are provided about how social media could be used more effectively by truly connecting with communities to improve community preparedness and resilience.

Introduction

The Australian 2019–20 bushfire season was extreme, resulting in loss of life, property and wildlife and caused environmental destruction. By early December 2019, large swathes of NSW were blanketed in smoke and poor air quality had become an issue for many areas, including Canberra and the ACT. The uncontrolled bushfires that surrounded Canberra were reminiscent of the bushfire tragedy of 2003 in which 4 lives were lost and over 500 houses were damaged or razed when bushfires crossed into Canberra suburbs. During a crisis such as a bushfire, information from trusted sources about risk and safety becomes crucial, as it may influence life-and-death decisions.

The Royal Commission into National Natural Disaster Arrangements was established in February 2020 to investigate the ‘coordination, preparedness for, response to and recovery from disasters as well as improving resilience and adapting to changing climatic conditions and mitigating the impact of natural disasters’ (Royal Commission 2020a). The final report, tabled in Parliament in October, noted that ‘there are confusing and unnecessary inconsistencies in some of the information provided to the public’ (2020b, p.28) and that ‘governments should educate people and provide accessible information to help them make informed decisions and take appropriate action’ (p.21). Findings in the report highlight the need for improved communication with the public, including timely and accurate warnings, echoing recommendations from previous reviews. From the perspective of emergency services organisations, digital communication platforms, including social media, have become crucial communication media to keep communities informed (Yell & Duffy 2018). While many studies have been undertaken to learn what constitutes good social media practices in crisis communication from a practical perspective, there are fewer on how to apply research and evidence-based recommendations to improve strategic and tactical crisis communication.

Significance of trusted sources during a crisis

Clear and unambiguous information from trusted sources about risk and safety becomes crucial in a crisis. A report on COVID-19 news and misinformation found that government was the second most trusted source of information after scientists and health experts. People in Australia were also less inclined to think that government exaggerated claims about the virus and its effects, compared to news media and social media (Park et al. 2020a).

In Australia, the trusted organisations and sources of information in a bushfire context are government agencies such as emergency services organisations, rural fire services and the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (radio, television and online). While news media remains the most important source of information during crises, government agencies are significant contributors to crisis communication as the most trusted and critical source of information. Previous studies, with a focus on organisational crisis communication, suggest that community resilience in preparedness for a bushfire event is enhanced by deep and sustained engagement and communication with communities prior to, during and after the event (Prior & Paton 2008; Sharp, Millar & Curtis 2009). While receiving accurate, timely and reliable information is important, affected community members need to ask questions and seek information from authoritative personnel and be approached in a dialogic, rather than didactic way (Sharp, Millar & Curtis 2009). Further, community engagement, coupled with mass communication techniques, encourages better collective preparedness. Specifically, this can help individuals build trust and confidence in the organisations that are responsible for providing information and, consequently, promote collective action and better outcomes (Prior & Paton 2008).

Characteristics of effective crisis communication

Steelman and McCaffrey (2013) identified characteristics of effective crisis communication. Their framework brings together best practice and theoretical literature from risk communication and crisis communication to derive key characteristics associated with best communication practices. The work highlights that ‘effective communication is often identified as a key practice to move towards the desired goal which is more disaster-resilient communities’ (p.683). The framework consists of 5 characteristics:

- Engage in interactive processes or dialogue.

- Strive to understand the social context in which the threat is situated.

- Provide honest, timely, accurate and reliable information.

- Work with credible sources, including authority figures when appropriate.

- Communicate before and during a crisis.

Evaluating the data collected in this study against this framework draws out the areas of crisis communication where Facebook can usefully contribute.

Social media and crisis communication

Digital platforms have become valuable resources, allowing immediate access to quality information and news. Staying up to date with information is particularly essential in a crisis with citizens thirsty for credible, fast news and information (Park et al. 2020b). Social media has become increasingly popular as a source of information and news. In the study ‘COVID-19: Australian news and misinformation’, Park and colleagues (2020a) found that social media is the second most used source of information about COVID-19 and the pandemic. Crisis communication research shows that social media is a critical component of crisis communication as ‘it creates opportunities for immediate transmission of important crisis information to as many people as possible’ (Eriksson 2018, p.538). In this context, it would be limited to as many people who are using Facebook and who have sufficient capability to understand English. Research into crisis communication during health crises highlights the need for organisations to pre-establish a strong social media presence on multiple platforms before the crisis to optimise communication during the crises (Guidry et al. 2017). Frequent, consistent and interactive communication with users, where the conversation is already taking place, plays a significant role in building trust (Guidry et al. 2017). People go to the source of information they trust in times of crisis and are, increasingly, searching for current and local information using social media channels.

Researchers have recognised the importance of social media use in crisis communication practice. Eriksson (2018) highlights the contribution of research to evaluation, particularly the use of social media, and how research can develop evidence-based recommendations to improve communication practice. In line with other researchers (Steelman & McCaffrey 2013; Prior & Paton 2008; Sharp, Millar & Curtis 2009; Eriksson 2018) demonstrated the need for crisis communication to be based on community engagement principles and practices, which means extensive community involvement during all phases of the crisis life cycle. Guidry and co-authors (2017) revealed that social media messages are likely to be most effective when they come from organisations that people are familiar with and trust. Message effectiveness is also enhanced when based on ‘the strategic use of risk communication principles such as solution-based messaging, incorporation of visual imagery, and acknowledgment of public fears and concerns’ (Guidry et al. 2017, p.477).

The study

Why and how organisations build trust with audiences and stakeholders before an event and how they balance the gravity of a situation with a hopeful outlook is of direct relevance to this study. This study focused on the use of social media by particular organisations as part of their communication plans. The organisations chosen were the NSW Rural Fire Service (NSWRFS) and the ACT Emergency Services Agency (ACT ESA). The Orroral Valley bushfire in January 2020 was used to examine the interplay between the 2 agencies and compare the use of social media in the context of this fire and how it contributed to community engagement and communication during the crisis. The Orroral Valley fire was selected as a case study as it was the only fire during the last bushfire season that began within the ACT and had the potential to threaten property and lives.

As the ACT is geographically located within NSW and fires are not confined within state boundaries, residents of the ACT were sourcing information from NSW sources as well as those from the ACT. In the period immediately before the outbreak of the Orroral Valley fire, ACT residents were monitoring fires over the border in NSW via the NSW RFS.

Method

This study used content analysis in a mixed-method approach to explore how the 2 agencies managed their social media communication during the Orroral Valley bushfire. The data collected comprised unique Facebook posts from the official ACT ESA and NSWRFS Facebook pages between 20 January and 5 March 2020. The Orroral Valley fire started on 27 January and was declared as extinguished on 27 February. The peak fire days were from 27 January to 10 February, when the fire was declared as contained.

The total number of posts was 613; 397 from the ACT ESA page and 216 from the NSWRFS page. Of these, 47 per cent of posts on the ACT ESA page were related to the Orroral Valley bushfire and 13 per cent of posts on the NSWRFS page were about the Orroral Valley/Clear Range fire. Focusing on the peak fire period enabled an in-depth analysis of the posts explicitly relating to the fire and reduced the risk of diluting the findings with non-related posts. The content analysis was conducted against 4 characteristics and measures from the Steelman and McCaffrey (2013) framework (see Table 1).

Table 1: Steelman and McCaffrey (2013) framework and measures.

| Characteristic | Quantitative measures | Qualitative measures |

| Engage in interactive processes or dialogue to understand risk perspectives and how they might be addressed. | Statistics (followers, shares, likes, comments). | Opportunities to engage the agencies. |

| Strive to understand the social context so that messages and content can fit the circumstance. |

Types and attributes of content. Application of the National Framework for Scaled Advice and Warnings to the Community. |

Provision of location or region-specific information. |

| Provide honest, timely, accurate and reliable information. |

Number and frequency of posts. Types and attributes of content. |

Key messages in media conferences. |

| Work with credible sources that have legitimacy, including authority figures, where appropriate. | Statistics (followers, shares, likes, comments). | Visibility and credibility of leaders and spokespeople. |

Posts were categorised by type of content (text, video, images, banners) and attributes of content (tone and style, length, number and frequency and accessibility). This was used to analyse each agency’s understanding of the social context and information provided. The different Facebook properties such as numbers of followers, shares, likes and comments was used to analyse interaction with users. In addition, the number and frequency of posts related to forums and engagement activities were measured. Posts were qualitatively analysed to draw out similarities and differences in approaches by the agencies in connecting with users and increasing the credibility of sources.

Results

By examining the types and attributes of the content, comparisons were made between the agencies to evaluate the different approaches against the characteristics of effective crisis communication as defined in Steelman and McCaffrey’s (2013) framework. Table 2 shows a quantitative comparison.

Characteristic 1 - Engage in interactive processes or dialogue

In line with their official communication plans, both agencies use Facebook as a one-way communication channel to provide information to the community during bushfires. While this one-way broad cast of information ‘improves transparency’ as defined by the Australian Government 2.0 Taskforce Report (2009), the data does not support a finding that either agency used Facebook to increase ‘participation’ and ‘collaboration’, the other headline goals of the government’s 2.0 strategy. Within the framework for official communication in natural disasters, the ACT’s strategies to provide ‘timely, effective fire danger information, advice and warnings about bushfire events’ specify a wide range of communications methods and appropriate public information protocols (ACT Government 2019, p.38). The NSW Government State Emergency Management Plan specifically lists social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter and Instagram as appropriate channels to broadcast warnings and messages (NSW Government 2018, p.14). Neither agency prescribes two-way engagement or collaboration with communities using social media.

To examine the engagement in interactive processes of the two agencies, the number of followers, shares, likes and comments were compared. Table 2 shows the comparison for the peak fire period 27 January to 10 February 2020. The data highlights a high level of community interest in the information provided by the 2 agencies and the desire to engage with the content. We also looked for opportunities for people to seek further information and clarification, including response posts (in response to community questions), promotion of community forums and door-knock campaigns. These were observed in ACT ESA posts only.

Characteristic 2 – Strive to understand the social context

To assess the extent to which each agency demonstrated this characteristic, a comparison was made of the types and attributes of content, the use of visual content, whether the posts included location or region-specific information and if the National Framework for Scaled Advice and Warnings to the Community was used. The results showed striking differences in the social media communication approach between the 2 agencies (Table 2).

Table 2: Comparison of types and attributes of content and interactions.

| ACT ESA | NSWRFS | ||

| # of posts | 397 | 216 | |

| # of posts about Orroral Valley/Clear Range Fire | 188 (47.4%) | 28 (13.0%) | |

| Types of content |

Text only |

213 (53.7%) | 43 (20%) |

|

Video |

66 (16%) | 26 (12%) | |

|

Images |

125 (31%) | 143 (66%) | |

|

Infographics |

28 (7%) | 93 (43%) | |

|

Coloured banners |

188 (47.4%) | 66 (30.5%) | |

| Tone |

Positive |

11% | 12% |

|

Neutral |

87% | 88% | |

|

Negative |

2% | 0% | |

| Length |

Short (less than 50 words) |

30% | 94% |

|

Medium (50-150 words) |

29% | 6% | |

|

Long (over 150 words) |

41% | 0% | |

| Facebook followers as percentage of population | 102,941 (>25%) | 748,927 (10%) | |

| Interaction |

Likes |

158,834 | 230,219 |

|

Shares |

41,046 | 53,971 | |

|

Comments |

33,096 | 17,658 | |

| Response posts | 4 | - | |

| Community forums | 9 | - | |

| Door-knock campaigns | 4 | - | |

NSWRFS fire posts consisted predominantly of images and infographics, text in dot points and were short in length, whereas ACT ESA fire posts included the warning system coloured banners, were long and text dense without headings. Overall, NSWRFS included many more images and infographics in its posts (66 per cent for NSW and 31 per cent for ACT ESA) with 43 per cent of their total posts including an infographic such as a graph, table or map to visually represent information. The majority of NSWRFS posts about specific fires included an infographic such as a fire prediction map or chart. Only 7 per cent of the ACT ESA’s posts included an infographic.

In terms of attributes of content used by the agencies, most posts, text and audio were neutral (official) in tone. Both agencies tailored messages to localised audiences to some extent through titles of their posts and specific content within the posts. During the peak fire period, both agencies posted videos to their Facebook pages in approximately the same proportion.

Use of visual content in social media crisis communication

As shown in Table 2, NSWRFS used a combination of text and images with infographics. These appeared in 44 per cent of its posts, whereas the ACT ESA included infographics in only 7 per cent of posts. More than half of the ACT ESA posts comprised text only, whereas approximately 1 in 5 NSWRFS posts used words exclusively. The majority of ACT ESA posts containing critical information about the fire were commonly over 350 words where none of NSWRFS posts were in the long category; the majority (94 per cent) being in the short category.

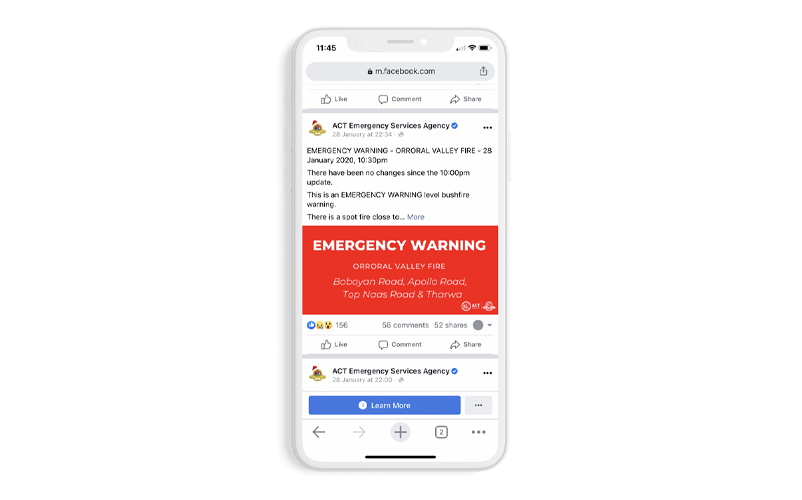

ACT ESA posts were lengthy containing over 350 words with the warning banner at the end.

Characteristic 3 - Provide honest, timely, accurate and reliable information

Consideration of the types and attributes of content and number and frequency of posts provides a gauge of how well the agencies met this criterion.

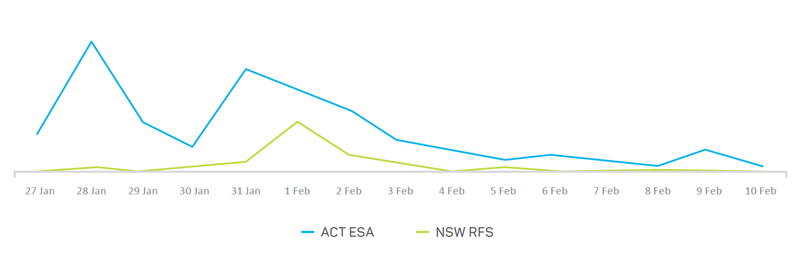

ACT ESA erred on the side of providing more detail rather than less, whereas NSWRFS posts were more likely to be short with critical messages and an image. Not surprisingly, the number and frequency of posts increased as the fire activity and warning level increased (Figure 1). For example, on the day the fire started (27 January), there were 11 posts on the ACT ESA page. The following day, there were 37 posts, 29 posts on 31 January, 24 posts on 1 February and 18 posts on 2 February. On those days, the fire warning level was at ‘emergency’ level. Similarly, on the NSWRFS page, there was one post on 28 January, 2 on 30 January, 3 on 31 January and 14 on 1 February when the fire crossed over into NSW and reached emergency level. During the media conferences, both agencies presented factual information about the fires and conditions on the firegrounds, including clear advice that fires were unpredictable and concrete predictions could not be given.

Application of the National Framework for Scaled Advice and Warnings to the Community

Both agencies provided regular updates on their Facebook pages about what was going on in the various firegrounds and, observing the requirements of the national warning system, provided predictable updates depending on the level of warning. ‘Emergency’ warning level requires an update every 30 minutes, ‘watch and act’ every 2 hours and ‘advice’ level every 24 hours. Both agencies provided different levels of detail in their posts but were consistent in the provision of that information on a predictable basis. In line with the framework, both agencies consistently used coloured banners to highlight the current warning level so that people could see it at a glance. However, on a small mobile screen, the coloured banner was not visible until the user scrolled to the bottom of the post.

Figure 1: Orroral Valley Fire/Clear Range fire posts per day.

Characteristic 4 - Work with credible sources who have legitimacy

This specific criterion was evaluated based on qualitative analysis of the media conferences streamed by both agencies and the visibility and credibility of their leaders and spokespeople. Eriksson (2018) emphasised that using an official representative and credible source will positively influence the sharing and propagation of information online. Both NSWRFS and ACT ESA had leaders with a high personal level of trust and credibility; Commissioner Shane Fitzsimmons (NSWRFS) and Commissioner Georgeina Whelan (ACT ESA). These individuals were front and centre for their agencies during the fire season and were often flanked by other senior members of their agency and from other organisations.

The media conferences were used to present messaging related to the unpredictable nature of bushfires and that successfully fighting the fires was dependent on many factors such as wind speed and direction, humidity levels, temperature and terrain. The ACT ESA streamed these conferences live on Facebook, which gave people the opportunity to see the people directly in charge and to build credibility and provide comfort to the viewers. Both agencies took opportunities to mention the good work of firefighters, other agencies and organisations through posts about awards, sacrifices, acts of generosity and gratitude.

Facebook as an official crisis communication tool

In 2010, Government 2.0 emphasised the importance of government to be more open, accountable and responsive and it articulated a commitment to communicate using online technologies (Heaselgrave & Simmons 2016). Public sector organisations are increasingly using social media for corporate and organisational communication and public relations (Macnamara & Zerfass 2012). However, research has found that government agencies are extensively using social media mainly for traditional one-way communication and less for increasing participation and collaboration (Heaselgrave & Simmons 2016, Alam 2016).

Within the framework of official communication during disasters, the ACT Government’s official stance is to provide ‘timely, effective fire danger information, advice and warnings about bushfire events’ specify a wide range of communication methods and the use of appropriate public information protocols (ACT Government 2019, p.38). The NSW Government official plans specifically list social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter and Instagram as appropriate channels for broadcasting warnings and messages (NSW Government 2018, p.14). This shows that the importance of immediate and interactive communication using digital communication tools in a crisis is well recognised. While effective social media communication is well documented, the data in this study demonstrate that both ACT ESA and NSWRFS use Facebook as a one-way (broadcast) communication channel to provide information about bushfires and other emergencies. During the 6 weeks nominated for this study, the ACT ESA posted 397 distinct posts and nearly 50 per cent of those concerned the Orroral Valley/Clear Range fire. NSWRFS posted 216, 13 per cent concerning the fire. On the peak fire days, the number and frequency of posts increased as did the level of detail provided. However, there was little evidence that Facebook was being used as a collaboration or engagement tool. This study did not look in any detail at the public comments on the posts, however, a high-level perusal showed that many of the comments were people ‘tagging’ others to share information and to express gratitude for the work of the agencies, staff and firefighters. There were a considerable number of comments seeking clarification of information posted and information about specific services and local conditions.

In addition, over 98 per cent of active Facebook users accessed it through the app on a mobile device (Statista 2020). As such, information designed for a webpage may not be easily read on a smaller mobile phone screen. Long posts full of text are difficult to read on a mobile device. While the national warning level system provides for the use of a coloured banner, the ACT ESA Facebook posts had the banner at the bottom of the post, which is not visible until the user scrolls down.

Close engagement with communities through dialogue prior to a crisis supports the government in creating the right conditions for community resilience (Eriksson 2018). Through active engagement on social media a robust digital connection and relationship can be formed before a crisis occurs. That is, the organisation is more likely to become a hub for information as people know where to go for information when they need it. A known hub for authorised information can also provide a platform for combating false information and encouraging community and individual preparation activities. Many researchers recognise that crisis communication needs to be based on community engagement principles and practices (Prior & Paton 2008, Steelman & McCaffrey 2013, Sharp et al. 2009), which means extensive community involvement during all phases of the crisis. Prior and Paton (2008) also highlight that the quality of relationships with a community is as important as the information provided.

Conclusion

This study leveraged Steelman and McCaffery’s (2013) framework to highlight where agencies, in their use of Facebook, demonstrated the characteristics of effective crisis communication and identified areas for improvement. Both the ACT ESA and NSWRFS provided timely, accurate and reliable information and used credible and trusted sources and spokespeople. However, several opportunities exist to enhance their use of Facebook.

Strategically targeted engagement with affected communities will enhance government understanding about the maturity level of communities to prepare and respond in times of crisis. Active and ongoing engagement will help build capability and resilience within communities and trust in the organisation. Understanding the social context, what information people need in a crisis and when and how they use it to make critical decisions, will help agencies design effective communication products to promote a better community response.

As the number of Facebook users grows, the usefulness of text data for research is increasing and Facebook has become a useful platform to conduct empirical research about its users. A comprehensive analysis of the words (statements and questions) in the comments would yield a deeper understanding of what information people find useful and, combined with user research to design and test effective communication methods, would provide evidence for organisations to inform future strategic communication planning.