The Oso mudslide: reflections of an emergency manager

Rosemarie Lentini

Journalist, Rosemarie Lentini, talks with John Pennington, founder and Director of the Snohomish County, Washington, Department of Emergency Management.

Article

John Pennington was expecting 22 March 2014 to be another lazy Saturday − until the hill collapsed.

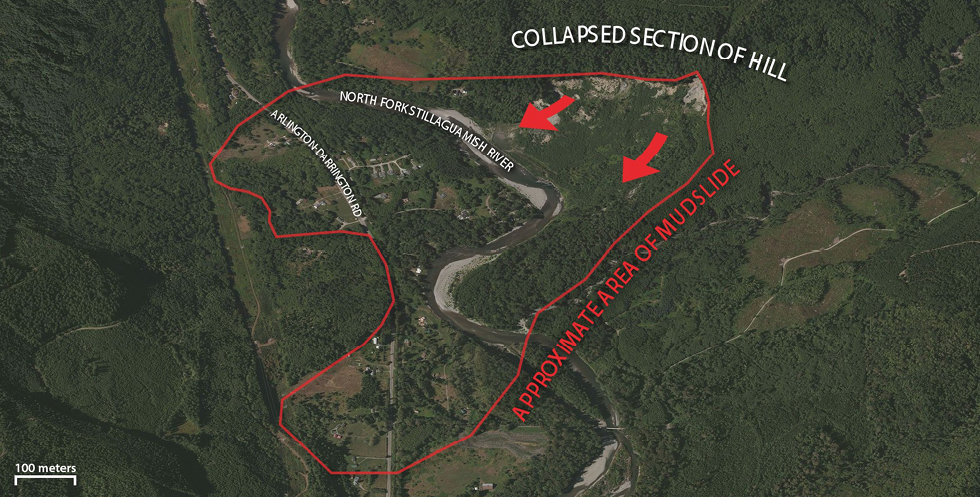

Tonnes of debris above Hazel Slide plunged into the North Fork of the rain-swollen Stillguamish River, creating a tsunami of mud that engulfed the logging town of Oso, Washington state in the U.S. Fast-moving quicksand loaded with trees and rocks killed 43 people, flattened 36 homes, dammed State Route 530 (a major highway), and caused more than $US50 million in damage. One fire chief said Oso looked like it had been ‘put in a blender and dropped on the ground.’1

The world’s attention focused on Mr Pennington, founder and Director of the Snohomish County, Washington, Department of Emergency Management who co-ordinated last year’s 37-day response. The former United States Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Regional Director has led or managed nearly 30 federal disaster responses, including deploying assets to support the Space Shuttle Columbia disaster and hurricanes Katrina and Rita.2 He was a founding executive member of the Anti-Terrorism Advisory Council of Alaska and is a senior member of the Department of Homeland Security’s Urban Area Security Initiative for Puget Sound.

John Pennington, Director of Department of Emergency Management, Snohomish County, Washington. Image: John Pennington

Despite his experience, Mr Pennington said the Oso mudslide − America’s deadliest − changed his view of disasters.

‘I learned from Oso that smaller events can be catastrophic, national level, internationally-focused and personally impactful.

‘This incident was just so complex. Initial reports were that perhaps the slide was 300 yards (274 metres) long by 400 yards (365 metres) wide. And now we know of course that it wasn’t.

‘It was one mile (1.6 km) by approximately one and a half miles (2.4 km) and caused a wave of destruction on a 50-mile (80 km) stretch of one state highway.

‘Because of the splintering of multiple communities, the tribal governments being impacted,3 the salmon, the mass fatalities, the debris management, it was just an extraordinary event that required the most dynamic examples of leadership that we’ve ever experienced and probably would ever experience,’ Mr Pennington said.

Snohomish County is a flooding and landslide-prone area in Washington’s northwest; a region that has experienced eight major presidential disaster declarations in seven years. Hazel Slide, the site of the Oso mudslide, has a history of collapsing, including in 2006. Geologists said Oso was the worst by far.

The mudslide followed weeks of heavy rainfall that, combined with the effects of logging and river erosion, ‘reactivated’ the 2006 slide.4 Recovery will take years.

Although Snohomish County has spent ‘millions of mitigation dollars’ building a resilient emergency management system, the mudslide at Oso exposed some shortfalls. It also revealed the ‘new normal’ in global disasters.

‘I don’t think that most jurisdictions are going to experience Hurricane Katrina or the earthquake in Northridge.5 The State Route 530 slide is the best real-world example of what a catastrophic incident is going to look like for most jurisdictions in the future.

‘Geographically small, geologically large, complex beyond your wildest imagination and requiring every asset and resource,’ Mr Pennington said.

Site of the mudslide in Oso, Washington state. Image: Jack Forbes produced for author

After reflecting on the response effort, Mr Pennington shared his recommendations for ‘fine-tuning’ at the Washington State Emergency Management Association’s annual conference in Spokane, Washington state, in September 2014.6 Some of the recommendations were:

1. Emergency operations centres need strategic ‘think tanks’

Two days into the response, the slide’s enormity came into focus. Emergency operations centre staff were frantically co-ordinating stabilisation efforts and dealing with ‘overwhelming media scrutiny’.

For Mr Pennington, a less reactionary, more strategic approach was needed. He took his deputy director, Jason Biermann, for a coffee to nut out a ‘big picture’ plan.

‘First responders were digging and searching, the helicopters were rescuing, but there had to be some other element co-ordinating the larger portion of the disaster.

‘You have all these personnel who are working tactically and some working strategically, but who is really thinking long-range strategically?

‘What happens if we don’t have this road back open within x-number of days or weeks or months? What are the cultural impacts to the three tribal governments? What happens to the endangered species in the salmon runs? What happens to the river as hazardous materials leach into it?

‘One of the lessons learned is that emergency operations centres need to be augmented by a think tank component.

‘It could have one or two individuals who are not policy makers, they are not people who work traditionally within the emergency operations centre, and they’re not tactical first responders.

‘Their jobs are to … synthesise all the intelligence and plan forward. When we created our own internal think tank, the process started to run more smoothly,’ he said.

One example was the management of community resource centres.

Difficulties arose when individuals seeking accommodation, food vouchers and other materials ‘were having to mingle with relatives of people who had died in the slide,’ he said.

‘Part of that strategic thinking was establishing separate venues so we were successfully able to keep those two populations distinct. Not apart from one another, because they needed support, but distinct from one another,’ he said.

2. Leaders should be empowered to lead

When the mudslide hit, Mr Pennington’s long-standing deputy director retired. His replacement was temporarily deployed, while another employee had joined the department just six weeks earlier. With just 14 staff, Mr Pennington had to co-ordinate about 2000 first responders and volunteers.

‘It was a unified command but it was more of a strategic unified command that I really found myself, to a large extent, facilitating, and it was a very different role for me.

‘I had the authority to co-ordinate the disaster, but the question of “did I have the statutory responsibilities or statutory authority to actually co-ordinate something this large?”, was very uncertain.

‘The final conclusion I drew, and what I instructed my senior staff, was just to lead.

‘If you see any vacuums in leadership, fill that vacuum until an attorney tells you not to do it. And the objective was that I had built very strong leaders here, more than just emergency management professionals.

‘I put them in positions of leadership in domains they were probably not really prepared for, but they succeeded,’ he said.

Snohomish County Emergency Operation Centre was activated in response to the Oso mudslide. Image: FEMA, Steve Zumwalt

3. ‘Regional teamwork’ is achievable with statutory change

Washington state is comprised of 39 counties, each responsible for managing disasters in their jurisdictions. To Mr Pennington, this is not the best use of resources. The Oso mudslide showed that intense catastrophic incidents stretch every resource. If several massive disasters hit at one time, how will responders cope? What’s needed is statutory change.

‘We have to develop a regional construct that will essentially say, yes there are 39 counties but there are actually 10 counties, as an example, which have such strong, robust emergency management functions, that they can become regional anchors to assist the state.

‘You would have state liaisons who come into these regional centres like Snohomish County which is large, robust, very proven, very effective, where we would basically help to manage, in co-ordination with four other counties, an entire region.

‘I think I now have the courage to say this needs to change or we’re going to have real issues,’ he said.

4. Australia and Washington state can learn from each other

Learning from the experiences of other countries is critical to building national resilience, Mr Pennington said.

Australia’s Memorandum of Understanding on Emergency Management Cooperation with the United States, first signed in 2010 and recently re-signed for another five years, facilitates this knowledge exchange.

‘Australia is faced with changing climate as much as we are in the U.S.

‘Where Australia would have raging wildfires that would overwhelm certain areas, the way you respond has to be just more than looking at it as, “Australia has an amazing wildfire risk”. Washington state has to look at it as more than “we have an extraordinary quake risk”.

‘So the term ‘all hazards’ becomes really critical.

‘In a changing world where climate is becoming something we have to face and address, not to mention the social impacts and the cultural impacts of disasters, we have to train to lead as individuals and as organisations.

‘That’s where there is a connection between Snohomish County, Washington state, and Australia.

‘Disasters don’t have borders, they shouldn’t have borders and there shouldn’t be boundaries.

‘While the jurisdictions vary a little, the reality is we’re facing the same thing and had better start speaking the same, common languages or we’re going to start to face unfortunate consequences,’ he said.

Tonnes of debris above Hazel Slide plunged into the North Fork of the rain-swollen Stillguamish River, creating a tsunami of mud. Image: Snohomish County Public Works

Footnotes

1 Snohomish County Fire Battalion Chief Steve Mason interviewed by CBS News, ‘Washington officials warn to expect the worst’. At: www.cbsnews.com/news/oso-washington-mudslide-survivors-starting-to-feel-disasters-impact [28 March 2014].

2 Space Shuttle Columbia disintegrated over Texas and Louisiana, killing seven crew, in 2003. Atlantic tropical cyclones Katrina and Rita hit the US in 2005.

3 Snohomish County has three self-governing Native American communities: the Tulalip Tribe, the Stillaguamish Tribe and the Sauk-Suiattle Tribe.

4 Geotechnical Extreme Events Reconnaissance Association investigation. At: www.geerassociation.org/GEER_Post%20EQ%20Reports/Oso_WA_2014/index.html [22 July 2014].

5 Hurricane Katrina hit America’s Gulf coast in 2005, while the 6.7-magnitude Northridge Earthquake shook Los Angeles in 1994. They are among the costliest disasters in US history.

6 View presentation at www.wsema.com/wsema-conference.