Abstract

Traditionally, the human face of emergency services organisations has lacked diversity. However, escalating natural hazard risks due to social, environmental and economic drivers requires a transformation in how these risks are managed and who needs to manage them. With communities becoming more diverse, building community and organisational resilience to more frequent and intense emergency events needs organisations to change from working for communities to working with them.

This requires greater diversity in skills and capabilities in the people who apply them, making diversity and inclusion a moral and business imperative. This paper summarises findings from an assessment of the diversity and inclusion literature relevant to the emergency management sector. Three case studies that are elements of the Bushfire and Natural Hazards CRC project, ‘Diversity and Inclusion: Building strength and capability’ are examined.

The research assessed the current context in which diversity and inclusion exist in each organisation and identified barriers, needs, challenges and opportunities. The major findings provide a basis to develop a support framework for effective management and measurement of diversity and inclusion.

Introduction

As stated in AFAC (2016), ‘Unacceptably low levels of diversity, particularly in urban fire and rescue services’ are widely acknowledged within emergency services organisations. In Australia, over the past two years, this has led to a sector-wide focus on the development of programs to address this deficit. At the sector level, AFAC convened the Male Champions of Change program in 2017 to redefine men’s roles in taking action on gender inequality in industry (Male Champions of Change 2018). It has also seen the growth in numbers of diversity officers in most emergency management organisations and the development of programs, frameworks and policy in this area. These have also been supported by industry conferences, including the Women and Fire Fighting Australasia biannual conferences since 2005 and the Diversity in Disaster Conference 2018.

Emergency management organisations are also responding to increasingly dynamic risks, constrained resources and changing technologies (Attorney-General’s Department 2011, Young et al. 2018a). As a result, these organisations are placing greater emphasis on strategic planning and collaborations that manage shared ownership of economic, social and environmental values. This requires the expansion of skills from traditional tactical response to strategic planning for preparedness, prevention and recovery (AIDR 2013, Bailey 2018, Attorney-General’s Department 2011, Young et al. 2015).

This improves understanding of how risks can affect communities and the development of comprehensive community-wide plans that allocate risk ownership and build resilience (Young et al. 2017). The diversification of activities undertaken by emergency management organisations and the need to represent diverse communities (e.g. Mitchell 2003) heightens the need for more diversity in workforces (Young et al. 2018a, Maharaj & Rasmussen 2018). Achieving this is not a straightforward task.

Project background

The ‘Diversity and Inclusion: Building strength and capability’ project began in July 2017. During the scoping phase, extensive consultation revealed the need to understand what constitutes effective diversity and inclusion implementation. In particular, what this means for emergency management organisations in terms of management and measurement. The research aim, therefore, was to develop a practical framework for the implementation of diversity and inclusion that builds on and leverages current strengths and expertise within emergency management organisations and their communities. Its purpose is to support better management and measurement of diversity and inclusion by providing a platform that uses evidence-based decision-making.

The project has three stages:

- understanding how diversity and inclusion operates within emergency services systems

- developing a suitable diversity and inclusion framework for the emergency services sector

- testing and using the framework.

This paper reports on the results of the first year’s work (2017–18). In this phase, the project examined diversity and inclusion systemically through a values, narratives and decision-making lens across organisation, community and economic themes. Aspects of diversity examined were culture and ethnicity, gender, demographic status (age and education) and disability (physical).

Case studies were undertaken with assessments conducted in the Queensland Fire and Rescue Service (QFES), Fire and Rescue New South Wales (FRNSW) and South Australian State Emergency Services (SA SES). These organisations were selected as representative the sector in terms of size, purpose and organisation structures. Community case studies and a community survey (Pyke 2017, McCormick 2017) were undertaken at the same time, but are not reported here.

Method

The literature review focused on what was effective in terms of diversity and inclusion practice and how it was measured. Literature on the systemic nature of diversity and processes that support its implementation, innovation and change management were sought. Google Scholar and Google Web were searched using the key words ‘effective diversity’, ‘effective inclusion’, ‘measurement of diversity and inclusion’, ‘management of diversity and inclusion’, ‘diversity in emergency services/ emergency management sector’, ‘inclusion in the emergency services/emergency management sector’, ‘systemic diversity’, ‘diversity systems and diversity process’ and ‘change management and innovation’. These terms were also searched substituting ‘organisations’ for ‘emergency services/emergency management sector’. In addition, agency-related searches of emergency management-specific studies and grey literature relative to Australia (ambulance, firefighters, police, State Emergency Services, government) were also undertaken.

In total, 126 documents were selected based on their salience and relevance to the core theme.

An audit of the images used on the websites of the case study organisations was completed. This included public and archived documents relating to diversity and inclusion activities in each organisation. Images were categorised according to the type of activity represented as well as the ethnicity, age and gender of people or images used. This helped to determine the key visual narrative being presented.

The interviews were held under the guidelines of an ethical research plan within Victoria University. This plan includes provisos that interview recordings and any transcripts made are kept confidential, that people not be identified via reported comments without their consent and that all quotes are used with permission.

Thirty-three, semi-structured interviews of up to an hour long were held with people nominated by each participating emergency management organisation. Interviewees covered a variety of professional and operational departments and ranged from executive to officer levels. This provided a cross-section of employees and diversity of ethnicity and gender. The interviews were recorded and key themes and observations were extracted and synthesised into the following subject areas:

- understandings of diversity and inclusion

- governance, policy and strategy context

- communication

- monitoring and evaluation

- organisation strengths

- barriers

- needs

- benefits

- opportunities

- vision of the future

Follow-up phone conversations were conducted with various interviewees for clarification. Coding across the subject areas was undertaken using a grounded-theory approach. Data and findings were verified with each case study organisation. The three sources of data were synthesised to identify common themes and nuances related to context. Two interviews were undertaken with Gloucestershire Fire and Rescue Service in the United Kingdom. This allowed for comparisons to be made and synergies to be identified that exist beyond the local context and that apply to emergency services organisations. Interviewees remain anonymous.

Challenges for diversity and inclusion practitioners

The literature review (Young et al. 2018b) revealed little consensus as to what is effective. It also revealed the need for empirical evidence to understand this better (Williams & ORielly 1998, Ely & Thomas 2000, Herring 2009, Piotrwoski & Ansah 2010). The role of context emerged as a key factor that could influence organisational effectiveness (Williams & OReilly 1998, Joshi & Roh 2009). Literature specifically covering diversity and inclusion in the emergency services sector was sparse, focusing predominantly on gender, the cultures that exist within emergency management organisations and the barriers to participation, particularly in firefighting agencies (Beatson & McLennon 2005, Branch-Smith & Pooley 2010). Data related to this area was ‘patchy’ and demonstrated ‘a lack of coordinated workforce planning across the industry as a whole’ (Childs 2006, p.33).

There was little direct connection to the innovation and change management literature to guide practitioners, even though the implementation of diversity and inclusion is closely aligned to these areas. Although there were many frameworks and maturity matrices developed for diversity and inclusion, there was no process that could be used to guide practitioners to implement diversity and inclusion within organisations (i.e. they describe what to do, but not how to do it).

There was also no overarching definition of ‘effective diversity’ within the literature. The following is a working definition developed to guide this project:

Effective diversity is the result of interactions between organisations and individuals that leverage, value and build upon characteristics and attributes within and beyond their organisations to increase diversity and inclusion, resulting in benefits that support joint personal and organisational objectives and goals, over a sustained period of time.

(Young et al. 2018b).

The diversity and inclusion nexus

Diversity and inclusion are two sides of the same coin. Diversity is often characterised as what is visible (e.g. ethnicity, physical disability, gender, age) and inclusion as invisible (e.g. education, values, culture, experience). In terms of practice, it can be represented as a two-stage process, moving from a reactive phase of demographic representation to a proactive phase of management and inclusion (Mor Barak 2015). Taking in ‘invisible’ characteristics that consider the whole person is important. Inclusion signifies active engagement where individuals can contribute as their ‘authentic selves’ and feel a sense of belonging within the organisation.

Inclusion is a relatively new area of study. Practice and measurement in this area are still being developed. However, its importance for effective diversity was recognised, especially for service organisations (Mor Barak 2015).

Diversity and inclusion in case study organisations

Most emergency management organisations have civil defence beginnings and have evolved as emergency and response-based organisations that rely on tactical decision-making. The existing institutional, organisational and social systems that have subsequently developed have resulted in dominant characteristics. These can be at odds with those needed for effective diversity and inclusion. It has resulted in a culture where traditions are strong. There is frequently resistance to change and, in the case of firefighting agencies where employment is well rewarded, it can lead to the ‘perfect storm’ of continued occupational exclusion (Hulett et al. 2008, Baigent 2005, Bendick Jr & Egan 2000, Eriksen, Gill & Head 2010).

Each organisation had different approaches to implementing diversity and inclusion. QFES uses a top- down, bottom-up strategic approach; using values and appreciative inquiry to inform organisational change. FRNSW applies a primarily top-down programmatic approach. SA SES uses a bottom-up ‘organic’ approach shaped by the needs of their communities.

These organisations are at different stages of implementation. FRNSW has the longest application of targeted programs. QFES integrates diversity and inclusion as part of implementing wholesale organisational change as directed by the Queensland Government in 2014. SA SES is just starting their formal implementation journey. Each organisation has different strengths related to diversity and inclusion and these are strongly influenced by the organisation’s history and specific context (e.g. governance structures, roles and resources).

A review of past and current public documents, such as annual reports, revealed that QFES and FRNSW had a longer history of diversity and inclusion programs than is reflected in current records. However, programs were not always continuous, especially in the QFES, suggesting that lessons may have been learnt but forgotten, or only existed in parts of the organisation.

Effective practice was found in each organisation. Initiatives of note were the QFES Transforms Leadership Program, the FRNSW Indigenous Fire and Rescue Employment Strategy and the SA SES lateral entry program to increase the representation of women in paid management roles.

Barriers and needs

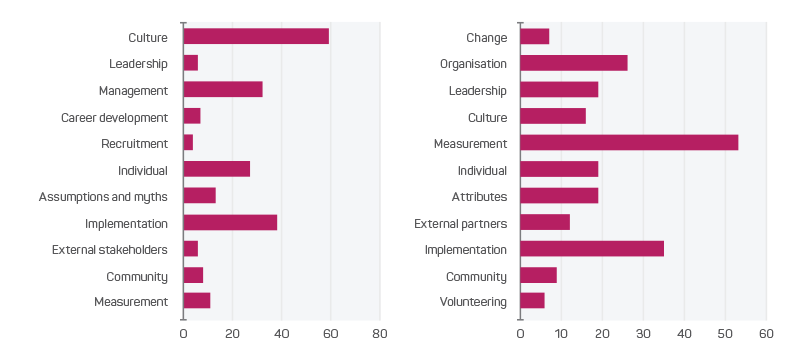

Interviews identified 213 barriers across 11 categories and 221 needs across 8 categories (Figure 1). The high number of responses in relation to barriers and needs could indicate the increasing awareness of diversity and inclusion. It may also be the result of pre-existing barriers and needs being brought to the fore as part of the change process.

Figure 1: Numbers of barriers (left) and needs (right) for diversity and inclusion in the case study organisations. Source: Young et al. 2018a

‘Culture’ within organisations was the largest barrier and ‘Management’ was identified as the largest need. The four smallest categories (Volunteering, Community, Partnerships and Change) are important issues for the emergency services sector that still requires work.

The theme of ‘Culture’ related primarily to aspects of organisational and institutional culture. The predominant barrier identified was the traditional, hierarchical, authoritative and predominantly male culture of organisations. This was reinforced by current structures, resulting in homogeneity that was the antithesis of diversity and a barrier to inclusion.

Important themes were facilitative management and leadership; being transparent and open, implementing actions that enable difference and empowering people to make good decisions. Managers also needed to differentiate between, and proactively manage, difficult and destructive behaviours. Many of the examples of difficult behaviours raised in the interviews were attributed to a lack of awareness where people ‘wanted to do the right thing’ but were unsure of what the right thing was. Needs identified were skills and training related to awareness and capability in areas such as conflict management, knowledge of different cultures, communication and language and the diverse needs of groups and individuals.

Benefits and opportunities

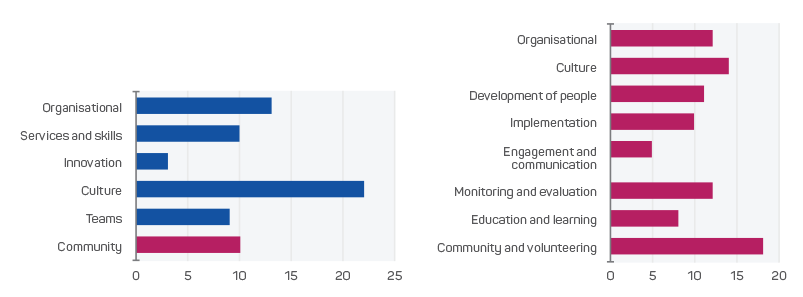

A total of 67 perceived benefits and 90 opportunities were identified during the interviews (Figure 2). Responses indicated a limited understanding of benefits and opportunities, which points to further development in this area.

Benefits fell into two categories: those to the organisation (85 per cent) and those to the communities they serve (15 per cent). Benefits to the organisation fell into five categories (blue bars in the left-hand chart in Figure 2). The largest was ‘Culture’ and the smallest was ‘Innovation’. These included monetary and non-monetary benefits.

Opportunities identified fell into eight areas (right- hand side of Figure 2). The largest categories were ‘Community and volunteers’, ‘Culture’, ‘Monitoring and evaluation’. The smallest were ‘Engagement and communication’ and ‘Education and learning’. If measures of effective diversity are to include opportunities taken and benefits realised, then knowledge of these areas within emergency management organisations could be improved.

The challenge of implementation

Implementation was prominent in the barriers and needs assessment (Figure 1). To date, many activities for diversity and inclusion have been reactive and, at times, counterproductive; focusing attention on ‘achieving diversity’ rather than the more complex implementation of inclusion. The use of quotas was particularly contentious. Participants also felt the ‘stop-start’ nature of programs eroded trust and resulted in a ‘two-steps forward, two-steps backwards’ outcome.

Participant reactions to diversity and inclusion included confusion, fear, resistance and difficult behaviours, particularly in units and brigades. This was exacerbated by the perpetuation of myths and assumptions related to diversity and inclusion as well as stereotyped views of diverse communities and individuals. The current lack of narratives and vision of what a diverse organisation looks like also contributed. Of the interviewees, those who performed operational roles found it difficult to visualise what their future organisations would look like. Without such vision, people are likely to anchor themselves to the past.

Figure 2: Number of perceived benefits of (left) and opportunities for (right) diversity and inclusion in the case study organisations. Source: Young et al. 2018a

Socialisation and priming of diversity and inclusion activities before they were implemented to test target group receptiveness was considered important. The greatest need was a better understanding of the benefits of diversity and inclusion for the organisations, individuals and teams and how it relates to people’s work and activities, particularly at brigade and unit levels.

Discomfort was expressed by people who were unsure about how to respond when a difficult situation arose with a person from a diverse cohort. This could result in ‘action paralysis’. For example, one interviewee was concerned that they might be regarded as racist or sexist if they had to discipline someone who was from a diverse cohort. This highlights that good skills at all levels within organisations are needed so that people feel they can conduct conversations without the risk of the conversation becoming ‘toxic’.

I think it doesn’t matter who you deal with, you just have to be respectful and communicate.

(Firefighter)

Knowledge and understanding of what constituted appropriate communication and language (verbal and non-verbal) was a common theme. Communication needed to be framed appropriately for different areas of an organisation because language (interviewees reported) ‘is different between operations and upper- level management’. It was also considered important to have common agreement on key words to enable consistent interpretation, particularly in relation to values. For example, ‘respect’ in an inclusion context means listening and responding mindfully to all people, whereas in a response context, it could mean being obedient to superiors and those in authority. The use of storytelling was also raised as a powerful tool to create connection to and understanding of diversity and inclusion.

Authentic actions, a diversity of people at leadership levels, long-term programs and trust were all seen as critical for effective diversity and inclusion.

If you see (only) one stereotype, then you may think twice about applying for a job here.

(Manager)

Overall, it is important that organisations provide environments that are ‘culturally and emotionally safe’ where people do not experience negative repercussions if they speak up.

Organisational characteristics

The characteristics of emergency management organisations that contribute to the status quo and those needed to implement effective diversity and inclusion are very different. This presents a challenge as organisations will need to change to allow for growth of these new characteristics while maintaining their current response capability:

Developing new organisational characteristics starts with understanding the attributes, capabilities and skills that currently exist as well as developing and integrating characteristics that effectively embrace diversity and inclusion.

We recruit a certain type of person to do a certain job, and at some point we ask them to do a very different job, which requires very different skills

(Manager)

Table 1 was extracted from interviews and the literature and compares dominant characteristics of traditional organisations with those of effective diversity and inclusion. The idea is not to replace characteristics in the left column with those on the right, but to identify where these characteristics may already exist in their organisations and communities so that the development and integration of these can be planned, to ensure consistency and enhancement of organisational activities. This can be used to plan transitions and identify where systems and processes may need adjustments.

Table 1: Comparison of typical characteristics with traditional emergency services organisations and those of effective diversity and inclusion.

| Characteristics of emergency services organisations | Characteristics of effective diversity and inclusion |

| Hierarchal | Valuing everyone, equality |

| Tactical | Strategic |

|

Primarily technical skills focused |

Primarily soft skills focused |

|

Authoritative leadership that directs areas of an organisation |

Enabling leadership at all levels of the organisation |

|

Shorter-term decisions |

Long-term visions |

|

Reactive |

Reflexive |

|

Resistant to change |

Continuous change |

|

Traditional - built on the past |

Forward focus - embracing the future |

|

People working for the organisation and communities |

People working with the organisation and communities |

|

Inward thinking with an organisational focus |

Outward thinking across all of society |

|

Directive communication |

Interactive communication |

|

Fixes things within a timeframe |

Not fixable, requires ongoing management for the longer-term |

|

Knowing and not making mistakes |

Not knowing and learning from what doesn't work |

|

Positional power |

Empowerment of individuals |

Source: Young et al. 2018a

Complexities

Emergency management organisations have a distinct organisational structure. They are directed and influenced by external agencies and institutions, such as government, and have limited ability to act in some areas. They often have competing priorities and some are highly resource-constrained, which can make it difficult to sustain programs.

The interviews revealed a number of ‘double-edged swords’ that were both enablers and disablers of diversity and inclusion:

- Team culture was considered a strength for organisations as it supported service delivery. However, the close-knit ‘family’ nature of teams, particularly at unit and brigade levels, could exclude those ‘not in the family’. This could lead to conflicts of loyalties and an ‘us and them’ attitude where individuals prioritise the team over the organisation. This could lead to inappropriate and covering-up behaviours.

- Working conditions in some organisations, particularly in the permanent firefighting cohort, provided a strong motivation for people to join and stay. This leads to low attrition rates that can make it difficult for organisations to change the composition of their workforce.

- A strong sense of organisational identity created a sense of pride but could also create barriers to change.

- Diversity of thought in the organisations was regarded as positive but can create conflict and confuse people if it was not well managed.

- An established response narrative engendered trust in the community and enhanced organisational reputation. However, it could reduce the community’s ownership of disaster risk and create unrealistic expectations as to the level of service agencies can deliver. It could also entrench ‘hero’ narratives. This could reinforce a sense of entitlement, hierarchical approaches and notions of being special, which could be exclusionary.

Findings

Findings from the interviews reinforced conclusions from the literature review that effective inclusion is the critical component that enables effective diversity and that this is a long-term and, at times, difficult proposition.

Doing diversity without inclusion is like jumping out of a plane without a parachute. (Executive)

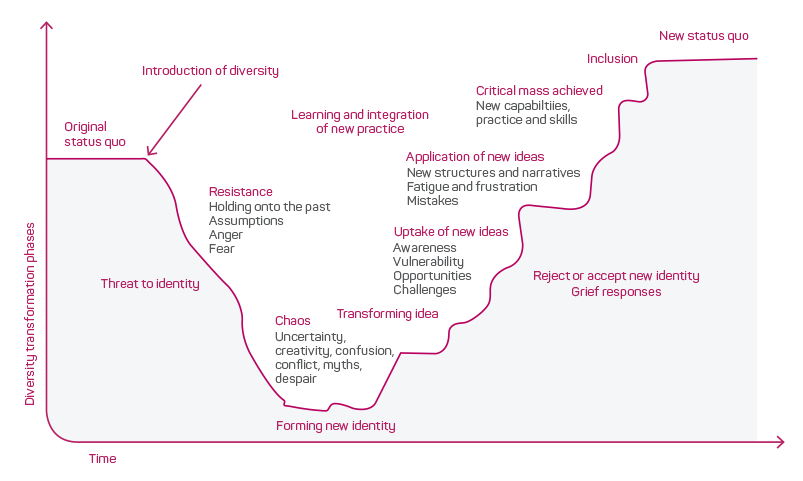

Figure 3: Phases of the diversity and inclusion transformation process. Source: Young et al. 2018a (adapted from Satir et al. 1991, Kübler-Ross 1993, Gardenswartz & Rowe 2003, Rogers 2010)

Key findings:

- Response-based and hierarchical structures, processes and decision-making with ‘fix it’ and ‘fit in’ cultures were predominant in the organisations. These are often considered of lesser value and are at odds with the strategic approach and people skills required for diversity and inclusion.

- There was a lack of awareness of appropriate language use and behaviours in relation to members from diverse cohorts and communities as well as the skills and capabilities they may have.

- Each organisation had different organisational cultures within them and there were cultural gaps, particularly between upper management and brigades and units.

- Interpretations of diversity and inclusion were varied. However, the predominant understanding was it being about ‘men and women’. How different diversity intersects (e.g. a gay member of a culturally and linguistically diverse community in a rural area) and how specific needs arising from this could be managed were less well understood.

- The diversification of skills and tasks in some organisations over the last ten years (Maharaj & Rasmussen 2018) is not fully represented in current public narratives.

- The visual audit of websites found the predominant visual narrative was of men of Anglo-Saxon appearance undertaking response-based activities. This limits the representation of employees and activities undertaken by organisations, which could discourage engagement of diverse cohorts.

- The greatest barrier to diversity and inclusion was culture and the greatest need was in the area of management.

- There was limited knowledge or valuing of the attributes and capabilities of diverse communities and individuals. This is an important component for communication that supports inclusive partnerships.

- Diversity and inclusion was not well integrated into organisational systems and processes nor connected to day-to-day decision-making.

- There are deeply entrenched organisational and personal identities that are linked to heroism and response in many organisations. These were reinforced by media and some communities.

Effective diversity and inclusion is a complex change process that requires innovation and a change in the status quo. Resistance and grief can be expected and are a natural part of change. Implementation is long-term and requires approaches that are strategic, programmatic and allow for bottom-up growth of initiatives and innovation. Figure 3 illustrates the strategic change process of a diversity and inclusion framework for practitioners.

Conclusion

Diversity and inclusion in the emergency services sector sits within a broader context of the overall change organisations are currently experiencing as they adopt more strategic roles in emergency planning and mitigation. To date, implementation has been largely reactive and focused on demographic representation, but organisations are rapidly moving into the proactive phase of developing inclusion.

There is still a tension between diversity as a positive and organisational imperative and diversity programs that divert resources from important priorities. This barrier is a sign that emergency management organisations have yet to embrace diversity and inclusion capabilities and skills as part of day-to-day business activities.

Right now, there is a real opportunity to make a difference and change things for the better. (Director)

In the case study organisations, implementing diversity and inclusion is evolving. Although there is work to be done, existing strengths can be built upon and leveraged. Leaders are emerging and service delivery can be improved through greater understanding of diverse cohorts and their value to organisations. Developing attributes, skills, capabilities, structures and processes that support inclusiveness are critical to positive outcomes.

For emergency management organisations to realise the full potential of diversity and inclusion they must move beyond notions of good and bad to a better awareness and understanding of what works and what doesn’t, and why. It is important for organisations to understand and acknowledge the past and to develop tangible visions of the future where diversity and inclusion is integrated into people’s roles. Being an inclusive organisation that is truly diverse is a long road. However, the rewards are being recognised and progress is already underway.