Bushfire communities and resilience: What can they tell us?

Julie Ann Pooley, Lynne Cohen and Moira O'Connor

Abstract

Article

Introduction

Bushfires are a significant threat to many of our Australian communities. We have seen the devastation that can occur given the recent events like Black Saturday (February 7th, 2009). For these communities and for Australia the cost of this kind of disaster is unmeasurable. However in time to come we will quantify the cost in the given measures we have come to recognise and still it will possibly be known as the worst natural disaster in Australian history.

It is obviously difficult to understand where one begins to learn from the levels of devastation we see in large disasters like Black Saturday. Royal commissions, internal reviews, lessons learnt forums will all take place and there is no doubt that these are extremely important to understand what happened and to mitigate future events. However as researchers one of the most important things we can offer to the table is our research. It is an important opportunity to provide information, aid in understanding and offer experience with which our process of healing and recovery may continue and the cycle of prevention and preparedness begin.

This case study of a semi rural outer metropolitan community was undertaken to determine which factors are important in understanding the experience of community members living with the threat of natural seasonal bushfires. In order to address this aim an in-depth qualitative approach was used to obtain an understanding of the experience of living with this threat in a contextual, holistic way.

The use of qualitative methodologies allows researchers to examine the experiences, thoughts, feelings and ideas of community members. Qualitative data contributes a quality of ‘undeniability’ through a source of well-grounded, rich descriptions and explanations of processes occurring in communities (Miles & Huberman, 2002; Smith, 1978). Techniques, such as interviews and focus groups allow researchers to obtain knowledge and an understanding of issues for a smaller sample of participants in far more depth (Patton, 1990). These methods are also most appropriate when the researcher is attempting to understand complex systems, values or emotions.

Narrative interviews were used to explore complexities and processes and focus groups were used to validate findings.

For the purpose of this research, a narrative approach was considered most appropriate, as this would provide access to the salient views, values and reality of living in seasonally threatened bushfire community. Further to this, the study used two different techniques in order to obtain a rich and full understanding of the experience of living in a bushfire community. Narrative interviews were used in order to understand the complexities and processes that emphasised the community members’ experience (Mishler, 1991), and a focus group was used to validate the findings that emerged from the interviews with regard to what factors are important in living in a seasonally threatened community.

Research context

The setting for this study is the community of Darlington is a semi-rural eastern suburb of Perth, Western Australia. Located in the heavily timbered hills that lie to the east of Perth (40 kms from the city centre), Darlington forms a backdrop for the city of Perth and the Swan River. Established in 1886 Darlington has a population of 3 449 (1705 males and 1744 females) residents with 1 244 dwellings located in the area (Statistics, 2006). Whilst its location in the hills provides the main attraction for many residents, the natural environment contributes to the seasonal threat of bushfires. The shire area, of which Darlington is a part of, has historically been one of the most threatened, in the metropolitan region of Perth. It is estimated that there were approximately six large fires per year (and a lot of small ones) about twenty years ago.

Stage one - Participants

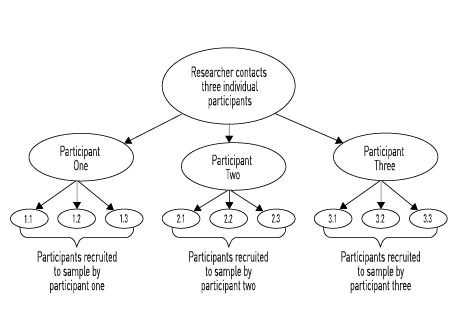

In order to build a sample of community members, a snowballing method of sampling was used (Patton, 1990). The sample comprised 15 participants, 10 females and 5 males, whose ages ranged from 18 to 68 years (M = 38.31; SD = 15.59). The participants came from various parts of the community, for example, some lived and worked in the local community while others lived in the local community but worked outside it.

A snowballing method of sampling was used to select participants in the study.

Materials and procedure

A narrative interview schedule (Reissman,1993) was utilized for all of the interviews. The researcher referred to the narrative storyline and read the following instructions to the participants.

“Tell me in your own words the story of the bushfire you were in. I have no set questions to ask you. I just want you to tell me about what happened to you, your family and your friends. Just tell it to me as if it were a story with a beginning, middle and an end. There is no right or wrong way to tell your story. Just tell me in a way that is the most comfortable for you”

Community members became involved by responding to a notice placed at the Darlington Library. A total of 15 interviews were conducted as saturation point was reached. Saturation point occurs when no new information elicited from subsequent interviews (Miles & Huberman, 2002).

Data collection and analysis

For each interview, data collection and analysis occurred simultaneously, and throughout the data analysis process, the data was organised categorically and was repeatedly reorganised and recoded according to themes recognised by the researcher. A list of the major ideas and themes generated were chronicled for each narrative interview and then compared with the ideas and themes resulting from previous narratives. Utilising thematic analysis allows the researcher to organise qualitative data coherently (Miles & Huberman, 2002). The result was a set of themes that were derived from the community members’ narratives.

Stage two

In order to validate the information obtained in stage one, this second stage utilized a focus group to triangulate the data (Searle, 1999). Triangulation relates to the utilization of different methods of data collection within a single study to confirm or validate the focus of the investigation (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). Therefore a focus group was held to explore the perspectives of a range of members in relation to living in a bushfire threatened community.

Participants

Community members involved in the focus were 6 female Darlington residents whose ages ranged from 24 to 72 (M = 35.28, SD = 17.59).

Materials and procedure

The same narrative format was used as with the interview with the focus group participants weaving their stories around one another. Some community members who responded to the noticeboard advertisement expressed the desire to meet together to discuss their experiences of living in a bushfire community. These particular participants formed the focus group.

Data collection and analysis

The focus group data were content analysed through the identification of themes elicited from the data. It was not important to glean quantitative information from the sorted data but to obtain themes that related to the experience of living in a bushfire threatened community. This process was checked and re-checked with a peer to ensure dependability and credibility of the identified themes.

Findings and interpretations

Five main themes were identified in the responses from the community members. The following themes represent those that emerged from the interview analyses. All of these themes were confirmed through analysis of the focus group data.

Sense of Community (SoC)

The first theme, which emerged consistently, was that of sense of community, or as referred to by many residents, ‘community spirit’.

There is a very big community spirit up here, huge actually and we live here because of that.

The components of sense of community, as presented by McMillan and Chavis (1986), appear in the participant responses. First, Membership, where people feel they belong or relate to others. Residents indicated that they feel closer to people in the community, as they had a similar experience of fires.

I think the fires unite you in a sense, there is that sharing type feeling that you get because you’ve all gone through it. I personally feel closer to the people who’ve been through a fire rather than those who haven’t.

Or

I would describe the community of Darlington as unique and insular, a community that is factionalised into smaller sub-groups which could be described as very “cliquey”. The individual groups are very diverse and have very well defined boundaries overlaid with a large amount of elitism.

There is a sense that people share events, like parties, picnics and fires (shared emotional connection). Needs of the individuals are met by living in Darlington (fulfilment of needs) and that this, in turn, produces influence. Sense of community is important to community members in relation to involvement in community activities and safety.

The community spirit is fantastic up here and you can really see that when something really bad happens.

Their sense of community is important to people remaining in the community after a disaster. The strong sense of neighbouring may possibly be a factor that helped people survive economically, emotionally and spiritually.

There is a lot of community spirit here and neighbours work to help one another with clearing and cleaning of their land.

People who actively participate when there is a disaster have positive attitudes toward their community and remain in the community after the crisis has passed, finding a strengthened sense of belonging. The appearance of this theme (SoC) supports earlier research by Bachrach and Zautra (1985), Bishop, Paton, Syme & Nancarrow, (2000), and Paton (1994) indicating that sense of community is an important resource for people in times of stress. Additionally, the present study is qualitative, which adds support to other authors that have addressed the relevance of SoC quantitatively. This also indicates that SoC is relevant across a number of hazard contexts i.e., hazardous waste, salinity and bushfire. The connection point for a sense of community may be the importance of social support networks.

Social networks and social support

Residents identified different social networks operating in the community. Social networks include formal and informal structures/groups in the community.

We have groups that have all manners of function (ratepayers, artists groups, the council….they all rally around the fire's event to get things done.

Residents were able to describe a wide variety of support ranging from, friends, family, neighbours, to community groups like the State Emergency Service, ratepayers association, the local council and the local volunteer fire brigade. This indicates that the residents of Darlington are aware of the different people within the community that they can call on for help or in times of need.

We began to receive lots and lots of phone calls from people trying to find out what was happening.

It also indicates that the community is fairly well connected and therefore has the structures available to allow members to communicate with each other.

People are made aware where their neighbour’s taps and hoses are in their yards, and they make plans with each about what they will do in the event of a fire. They also swap work and home phone numbers so that they can contact each other. They tell each other about the whereabouts of their kids and their pets.

In concert with the social network literature, this theme suggests that residents are accessing a number of other people, which relates to the size of the network people have and reporting access to different types of people, which refers to the structure of their network. This network is providing the bridge between the individuals and the community of Darlington.

As I reached the main road, the volunteer fire brigade arrived, along with a friend who took the boys and my husband who had been alerted at work and had come immediately home.

In terms of stress-buffering, the Darlington residents are utilizing their support networks and then forming others when needed (Fleming, Baum, Gisriel & Gatchel, 1982; Kaniasty & Norris, 1993; Padgett, 2002). The existence and recognition of the importance of community groups in Darlington may indicate that these social support networks were not necessarily disrupted in the aftermath of a bushfire, as they continue to be salient (Milne, 1977). The importance of the community-based groups/networks also related to coping in Darlington.

Coping

Coping was an important aspect of living in the Darlington community.

We now have a rule also that someone must always be on the property in case of fire.

Coping included a number of coping strategies such as emotional, problem-focused and avoidant. Many plans for managing bushfire threats have developed from problem-focused coping mechanisms.

I was dreadfully concerned about how they would cope once the smoke started to affect them. As well as feeling concerned for my class, I was also trying to contact Dick and Dora and finally located them.

Coping strategies are evident at the individual and community level. For example, the Darlington community has put in place a fine system to deal with those residents that do not clear fire breaks etc, ready for the next summer season.

As a direct consequence of this fire, we have fenced an area around our house and we now only garden in that area.

The coping strategies identified are indicative of the types of coping behaviour presented in the literature in relation to disaster events (Folkman & Lazarus, 1990).

Self efficacy

Related to coping is the way in which residents responded to situations, by doing things that they had planned to do, or made decisions about what to do in the face of little or no information emerged from the interviews and focus group. This is identified as self-efficacious behaviour.

I decided to do a reconnoitre and see what was happening, so I jumped into the van and drove partway down my property. From where I could see the smoke I thought that we didn’t look too badly off but I decided to keep an eye on things in any case.

The self-perceived capability of residents to respond in situations is important in terms of their actual performance and response. Residents indicated that they felt helpless when they did not know what to do, but when they become aware of the things they need to do they start to engage in preventative behaviours, such as gutter cleaning etc.

I felt particularly helpless because I didn’t really know what I was supposed to be doing. Families that live here need to have that sort of knowledge and at least some sort of plan about what they will take from the house in the time of the fire.

These responses indicate that people will make judgments about their ability to carry out actions (Bandura, 1977;1986). In some cases, they will act and in others, they will not. The sense of control needed, in an event where there is no control, is regained when the Darlington residents behaved self-efficaciously. This inevitably enables them to cope (Bandura, 2002).

Now that I know the correct things to do in the event of a fire, I feel that I would always stay at the house rather than leave. I know for example to shut the doors and windows and to watch for the outbreak of spot fires. We have also planted fire retardant trees on our land. We are also very conscious of fire prevention at the beginning of each summer season and do all the required clearing and cleaning of our land and around the house. For example, we move any chopped wood away from the house.

For residents that felt helpless the recognition of a need for a plan of action indicated that with self-efficacy, stress reduction may follow (Millar, Paton & Johnston, 1999).

Community competence

The final theme identified referred to the competence of the community. Community competency describes the processes and mechanisms in the community that takes place in order to carry out living in a bushfire threatened community.

I feel that a direct result of the fire is that people are far more aware now of the fire risk, that they are far more cautious, and that they are far more pro-active about keeping their gardens clean of rubbish etc.

In support of Sonn and Fisher’s (1998) argument, the Darlington community indicates competence, as it negotiates what needs to occur to manage and resolve the effects of bushfires, in other words, it copes with adversity.

As well as the strategies used by the school, the local volunteer fire brigade plays a huge part in the community with the work they do all year round.

I was very involved in that one, liaising between schools, ensuring the safety of the children, contacting the police and the fire brigade and making sure that the phones continued to be manned in order for parents to reach us to find out about the safety of their children.

Residents referred to the methods used by the community to plan for the future, and the processes that are employed in times of stress.

Several public meetings were held to plan strategies and organize people for any future dramas of this kind. This was planned right down to little things like neighbours ringing one another to discover if they are at home. The volunteer bush fire brigade does a tremendous job with its cleaning and clearing operations and the local residents who are unable to do this sort of work for themselves really rely on those volunteers to get the job done.

Since that fire, at considerable expense and using money that could have been spent elsewhere, the junior school has taken practical steps to create a safe haven for the children and members of the community in the event of future fires.

These plans are in line with some of Cottrell’s (1976) components of community competence, in particular, the identification and collaboration aspects. Therefore, although the Darlington community does recognize the repertoire of skills it has, other areas (needs identification, working consensus) were not identified, which may be relevant to enhance the community’s ability to cope with future disasters (Cottrell, 1976).

Discussion

The findings suggest a number of important issues. First, the themes that emerged from the present study support the themes that have been documented by other studies in the literature. For example, Bachrach and Zautra (1985) and Bishop et al (2000) identified a sense of community, self-efficacy and coping as important factors for community involvement in dealing with hazardous waste and salinity, respectively. Whereas Kulig (2000) concluded that the concepts of community competence and sense of community are important in understanding how landslide communities cope. The findings of the current study would, therefore, support the notion that these concepts are as salient to this semi-rural bushfire threatened community as they are to a small United States hazardous waste threatened community, an Australian farming community (salinity) and a Canadian rural community (landslides).

Women have very important roles in our community and are key players in community mobilization in pre and post-disaster activities.

Second, although previous studies have suggested that all of these factors may be important to disaster communities few studies have utilized the experience of the community members to determine the salient themes within a disaster community. For example, the studies carried out by Bachrach and Zautra (1985) and Bishop et al (2000) utilized quantitative scales to measure these concepts within a given community. The data collection methods used within the present study is arguably more contextually based as they were conducted with people living in the bushfire threatened community. The approaches used are therefore direct and inclusive. In addition, the use of the qualitative methodologies has provided a starting point to investigate factors that are directly relevant to individuals and to communities. The qualitative exploration of some of these factors in this disaster context adds to the empirical literature. The use of different data collection techniques (interviews and a focus group) strengthens the reliability of the findings through data triangulation (Searle, 1999). Further to this, it must be noted that a majority of the participants involved in this study were women (16 female and 5 male) and therefore the issues raised may be more indicative of female views of a disaster community. However, Enarson (1998) argues that women have very important roles in our community; they transmit knowledge about the family, community and the environment and are key players in community mobilization in pre-disaster and in post-disaster activities. Traditionally disaster research methods utilized have not been inclusive of women.

Finally, the results of the present study suggest that there is no single factor that represents the experience of living in a disaster community. These variables are however central to the way in which the Darlington residents deal with living in a community that is seasonally threatened by bushfires. At the community level, two distinct factors emerged as being important to the Darlington community. For Darlington residents it was the attachment (sense of community) that residents reported which determined their desire to remain in their community, and the way that Darlington, as a whole community, is able to facilitate and manage its processes (community competence) of being a community and coming together when and where necessary that was seen as important to the experience of the individual members.

The themes that emerged suggest that it is a combination of factors that are relevant to a disaster experience at the individual level and the community level. The factors identified (self-efficacy, coping style, social networks, sense of community and community competence) presented a more comprehensive picture of the possible variables that may mediate the disaster experience. It is, therefore, the interplay of these factors that are important to the experience of a community facing a natural seasonal disaster. Further to this is the relationship between, and the combination of, community competence and sense of community. Kulig (2000) refers to the combination of these variables as community resilience (see Pooley, Cohen & O’Connor, 2006). Therefore one of the conclusions from this study results is that by increasing the competence of the community and the attachment residents have for the community you may be targeting and effecting community resilience.

References

Bachrach, K. M., & Zautra, A. L. 1985. Coping with a community stressor: the threat of a hazardous waste facility. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. Vol. 26, No. 2, pp. 127-141

Bandura, A. 1977. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, pp.191-215.

Bandura, A. 1986. Self-efficacy. In A. Bandura (Ed.), Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory (pp. 390-453). Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice Hall.

Bandura, A. 2002. Growing primacy of human agency in adaptation and change in the electronic era. European Psychologist, Vol. 7, No 1, pp. 2-16.

Bishop, B., Paton, D., Syme, G., & Nancarrow, B. 2000. Coping with environment degradation: salination as a community stressor. Network, Vol. 12, No. 1, pp. 1-15.

Blong, R. 2003. Development of a National Risk Framework. Paper presented at the Australian Disaster Conference, Canberra.

Cottrell, LS, Jr. (1976). The competent community. In BH Kaplan, RN Wilson, & AH, Leighton (Eds.), Further explorations in social psychiatry (pp. 195–209).

Enarson, E. 1998. Through women’s eyes: A gendered research agenda for disaster social science. Disasters, Vol. 22, No. 2, pp.157-173.

Eng, E., & Parker, E. 1994. Measuring community competence in the Mississippi Delta: the interface between program evaluation and empowerment. Health Education Quarterly, Vol. 21, pp. 199-220.

Fleming, R., Baum, A., Gisriel, M., & Gatchel, R. 1982. Mediating influences of social support on stress at Three Mile Island. Journal of Human Stress, Vol. 8, pp. 14-22.

Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. 1980. An analysis of coping in a middle-aged community sample. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, Vol. 21, pp.219-239.

Kaniasty, K., & Norris, F. H. 1993. A test of the social support deterioration model in the context of natural disaster. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 64, No 3, pp. 395-408.

Kulig, J. C. 2000. Community resiliency: The health potential for community health nursing theory development. Public Health Nursing, Vol. 17, No. 5, pp. 374-385.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. 1985. Naturalistic Inquiry. London: Sage Publications.

McMillan, D. W., & Chavis, D. M. (1986). Sense of community: A definition and theory. Journal of Community Psychology, Vol. 14, pp. 6-19.

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. 2002. The Qualitative Researcher’s Companion. London: Sage.

Millar, M., Paton, D., & Johnston, D. 1999. Community vulnerability to volcanic hazard consequences. Disaster Prevention and Management, Vol. 8, No. 4, pp. 255-260.

Mishler, E. G. 1991. Language, meaning and narrative analysis. In E. G. Mishler (Ed.), Research Interviewing: Connect and Narrative (pp. 66-143). Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Paton, D. 1994. Disasters, communities and mental health: Psychological influences on long-term impact. Community Mental Health in New Zealand, Vol. 9 No.2, pp. 3-14.

Patton, M. Q. 1990. Qualitative Evaluation and Research methods. London: Sage.

Pooley, J.A., Cohen, L., & O’Connor, M. 2006. Community resilience and its link to individual resilience in the disaster experience of cyclone communities in Northwest Australia. In D. Paton & D. Johnston ( Eds) Disaster Resilience: An Integrated Approach. Springfield, Illinois: Charles C Thomas

Riessman, C. K. 1993. Narrative Analysis. London: Sage.

Searle, A. 1999. Introducing Research and Data in Psychology: A guide to methods and analysis. London: Routledge.

Smith, J. A. 1978. Semi-structured interviewing and qualitative analysis. Rethinking Methods in Psychology, pp.9-26.

Sonn, C. C., & Fisher, A. T. 1998. Sense of community: community resilient responses to oppression and change. Journal of Community Psychology, Vol. 26, pp.457-472.

Statistics, A. B. S. 2006. Census, 2006, from www.abs.gov.au/ausstats

About the authors

Julie Ann Pooley PhD is a Researcher and Senior Lecturer at Edith Cowan University.

Lynne Cohen PhD is Associate Dean in Teaching and Learning at Edith Cowan University.

Moira O’Connor PhD is a Senior Research Fellow at Curtin University’s Centre for Cancer and Palliative Care.