In view of the increasing magnitude and frequency of hazards, governments and international bodies are exploring innovative strategies for managing or reducing risks and responding to emergencies. As there is an urgent need for responsiveness, it is crucial to analyse response considering both the rapid and slow onset nature of these events. While public sector organisations grapple with the perpetual challenge of making decisions given the ambiguous, uncertain and complex characteristics of hazards, exploring the nature of institutional pressures emanating from stakeholder expectations and demands, the mechanisms that drive institutional responses and the typology of responses that can be deployed to reduce risks is crucial. This study involved extensive literature review and semi-structured interviews of public sector organisations and international non-governmental organisations funded projects. Both interviews and textual data based on observational findings from a multi-scenario tertiary-level disaster risk management education simulation-based learning activity were analysed thematically to aid the design and development of the framework presented. The findings offer opportunities for authorities and stakeholders to facilitate responsiveness while improving informed decision-making and political will for managing or reducing risks and emergency.

Introduction

Disasters can have multiple negative impacts on nations (IPCC 2014; CRED 2023) that often undermine the capabilities, skills and competencies available to respond before, during and in the aftermath of hazards (Dias et al. 2018; Ward et al. 2018; Shaw et al. 2022). This is in view of the adverse effect of climate change and issues associated with adaptive environmental governance and the perplexities of disaster risks that still presents enormous challenges for disaster risk reduction (DRR) organisational fields (IPCC 2012; IPCC 2014; Johnson et al. 2019). There is also the issue of knowledge management and translation of DRR policies into action (Pigeon 2013; Cleaver and Whaley 2018; Wisner et al. 2014) amid fragmentation, resourcing and risk communication methodologies (Abunyewah et al. 2020; Perera et al. 2020; Toinpre et al. 2025). While there is an urgent need for ‘responsiveness’ to address these issues, it is crucial to deconstruct response as an active and passive concept. This is bearing in mind the interconnected origins of disaster risks and the rapid and slow onset nature of natural hazards.

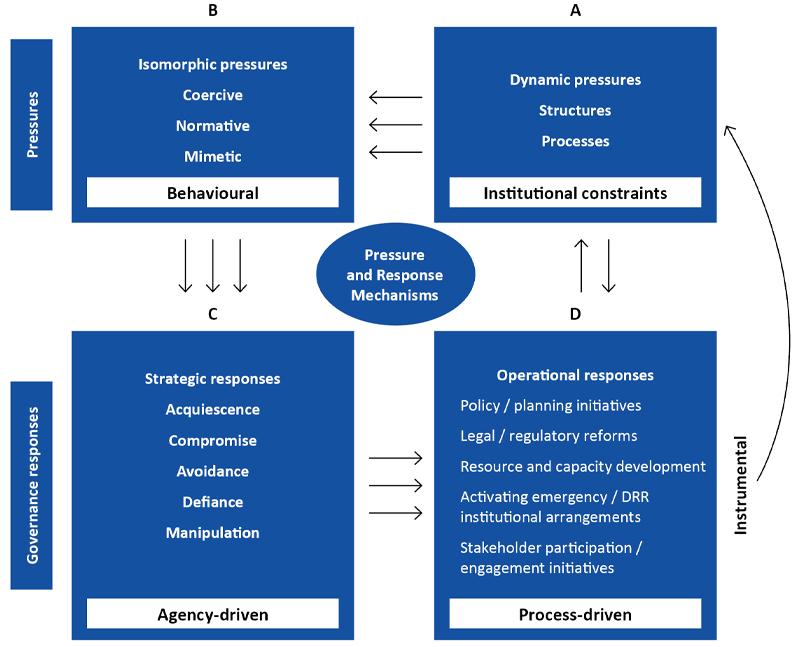

As public sector organisations and international bodies continue to define and explore innovative strategies to address risks (UNDRR 2016), it is crucial to identify institutional constraints that hinder organisational field responses to disaster risks and natural hazards; the institutional pressures that propel responses and the typology of responses that can be deployed to conform or resist pressures (Wisner et al. 2004; DiMaggio and Powell 1983; Oliver 1991). DRR organisational fields in this context refers to ‘the totality of actors and individual organisations with varying goals, values and interests whose statutory functions cut across providing public good and reducing disaster risks’ (Toinpre et al. 2018; Toinpre et al. 2024). Although, the institutional capacity for responding to emergencies and reducing disaster risks may be influenced by resourcing and an awareness of the nature of pressures (Norman 2014; Toinpre 2020), it is crucial to understand the processes through which they may be created, maintained and disrupted (Willmott 2011; Lounsbury and Boxenbaum 2013; Koskela-Huotari et al. 2020). This study therefore presents the Institutional Pressure and Response Mechanism (IPRM) framework to illustrate the complex interactions between pressures and institutional responsiveness while suggesting inter-operational network mechanisms that can assist in bridging response gaps. It analyses 41 semi-structured interviews sourced from public sector organisations and international non-governmental organisations funded projects in Imo State, Nigeria and secondary data sources such as journal articles, books, conference papers, government reports.

The study also builds on the observational findings from a co-authored published study on tertiary-level disaster risk management education simulation-based learning to textually analyse multi-stakeholder institutional response strategies based on case studies from Nigeria and Ghana (Tasantab et al. 2023). The simulation-based learning was designed using a formative assessment approach where information regarding existing flood risk conditions in both case studies were utilised. Finally, this study advocates for an adaptive environmental governance approach for the often-misconstrued notion of ‘response’ through a mutual learning alignment between the academia, public and private sectors. This approach offers opportunities for public sector organisations and stakeholders to enhance responsiveness to persistent risks and emergencies while facilitating informed decision-making, improving political will and significantly contributing to capacity building, competencies and commitment.

Literature review

Disaster risk governance and institutional pressure typologies

The concept of disaster risk governance and what it means to researchers in disaster risk management literature has evolved over the years (Klinke and Renn 2018; Djalante and Lassa,2019; Renn 2020). This evolution has witnessed gradual shifts from a reactive form of response to a more proactive response guided by international and transboundary agreements such as the 2030 Agenda on Sustainable Development, New Urban Agenda, Agenda for Humanity, Paris Agreement on Climate Change and the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030. These frameworks have provided an invaluable platform for decision-makers across various levels of governance to develop and localise institutional mechanisms to effectively reduce disaster risks within their respective jurisdictions (Renn et al. 2018). In addition, an appreciable number of studies have distinctively explored and distinguished between ‘collective decision-making’ (Okada et al. 2013; Ton et al. 2021) and ‘risk governance’ (Renn and Klinke 2014; Klinke and Renn 2018; Renn 2020). These definitions simply put together infers elements of institutional structures and processes aimed at regulating, reducing and controlling disaster risks through collective actions by individuals, groups, regions or nations across the globe.

Vulnerability is socially constructed and mainly driven by limited accessibility to power, structures and resources (Wisner et al. 2014; Oliver-Smith et al. 2017). Just as politics is manifested in visible contests, the ability to set an agenda as well as the underlying ideology that frames perceptions of what is an appropriate course of action, while the power influences how it works, who has it, and how it is deployed (Lukes 2021; Torabi et al. 2022). It is also based on both precedents that emphasises the view of resilience and risk reduction in cities posing the fundamental question over who makes decisions, what sectors or networks are prioritised, which risk conditions are to be addressed and what locations are to be assisted (Djalante et al. 2013; Djalante 2012; Meerow and Newell 2021). This philosophy has been based on the interactions between socio-political and economic ideologies, which have rippling effects on human behaviour and concomitant risk conditions necessitating a more holistic and integrated approach for risk governance and response (Paton and Johnston 2017; Djalante et al. 2013). While the magnification of the effects of hazards is embedded in the level of exposure and susceptibility, the persistence of disaster risks exacerbate effects on communities (Wisner 2022; Wisner et al. 2014). Public sector organisations are likewise susceptible to these risks and have to deploy response strategies based on established symbolic systems (i.e. rules, codes of conduct, laws, values and policies), routines (i.e. protocols, standard operating procedures, roles and scripts) and artefacts (i.e. technology and non-technology-based products/services). Further, the response strategies deployed are subject to the typology of institutional expectations and demands.

Vulnerability to hazards is associated with a state of function or dysfunction and nature of control exercised through governance and existing capabilities for risk reduction (Wisner et al. 2014). Hence, DRR is characterised by complex governance arrangements as well as cross-border cooperation (Tierney 2012) among dominant entities. Such entities (e.g. public sector organisations, non-government organisations, multinational corporations) allocate resources to develop systems, routines and artefacts adopted by subsidiary organisations or communities (Resell 2020). In addition, researchers argue that the existence of a common legal environment affects several aspects of an organisation’s behaviour and structure (DiMaggio and Powell 1983; Fadare 2013). The persistence of institutional constraints triggered by these interactions therefore channels root causes into specific forms of unsafe conditions (Wisner et al. 2014; Twigg 2015), which are further revealed through fragility of the physical environment and the economy. This affects livelihoods, household incomes, social groups at risk and limited public action (Wisner et al. 2014; Wisner 2016). Institutional theory therefore offers unique insights into an organisation’s environment in relation to institutional pressures (Oliver 1991). Three forms of institutional pressures propounded by DiMaggio and Powell (1983) that could be internally or externally exerted on public sector organisations and constituents include coercive, normative and mimetic pressures (Oliver 1991; Dhanda et al. 2022). The manner with which these pressures are responded to reflects on the field outcome and ultimately, the similarities exhibited by organisational norms, practices and standards of operation. This best describes ‘institutional isomorphism’. The coercive pressure involves the adoption of practices based on the prescriptions of dominant organisations, which have a higher sphere of influence and could lead to structural reforms (DiMaggio and Powell 1983; Zucker 1987). The normative pressure is linked to professionalism and relates to individual and organisational attainments and legitimacy driven attributes such as set targets and benchmarks, professional standards, standards of practice and certifications (Toinpre et al. 2018). Lastly, the mimetic pressures are manifested through the need for entities to adopt policies or practices under ambiguity and uncertainties (Piccolino 2020). This form of pressure is usually observed when imitating practices from other entities that have proven to be successful.

Institutional response typologies and strategic choices for risk reduction

Public sector organisations respond to stakeholder expectations and demands based on several antecedents. However, most of the response strategies are influenced by the type of pressures (i.e. coercive, normative, mimetic) being exerted and antecedent factors (i.e. cause, context, constituents, control or content). Conversely, depending on the constraints, public sector organisations may not be aware of stakeholder expectations and demands and may be under-resourced to respond, thus necessitating the need to assess pressure typologies and assess responses that can be deployed to improve DRR outcomes. Furthermore, as strategic responses are choices organisations make through self-interest or active agency, it reflects on the principles and standards of practice, organisational interests, resources and capabilities available (Wijethilake et al. 2017). These include:

- acquiescence

- compromise

- avoidance

- defiance

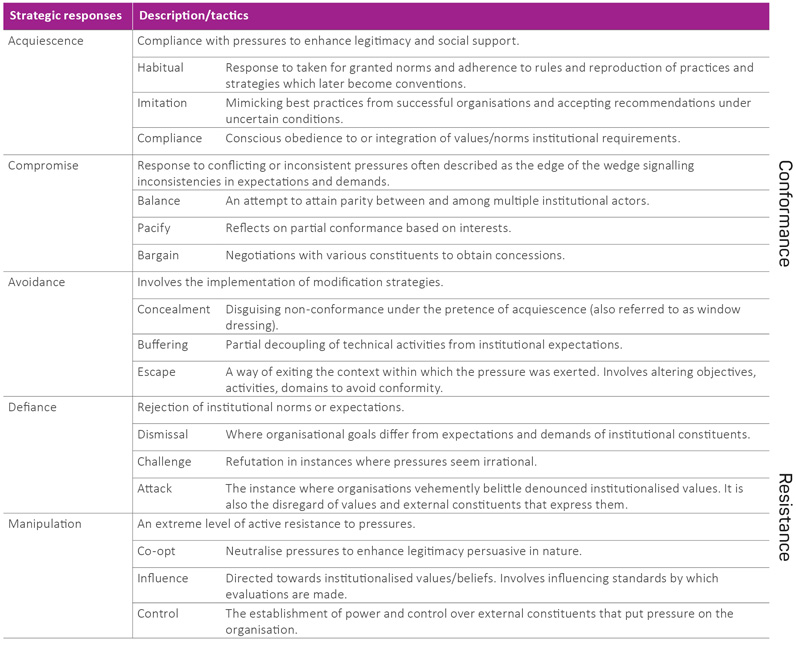

- manipulation (Oliver 1991), see Table 1.

Mintzberg and Waters (1985) argued that strategies may be deliberate (i.e. planned or intentional) or emergent (realised without intention). However, a deliberate strategy is realised exactly as prescribed or intended by an organisation and constituent actors, which result to operational responses.

By operational responses, we refer to deliberate actions aimed at reducing disaster risks. These sorts of responses are typically process-driven and can lead to the design and development of structural or non-structural risk mitigation measures using physical (e.g. critical infrastructure such as bridges, dams, culverts, dykes), social (e.g. community-based DRR initiatives) or economic (i.e. fiscal or monetary policies) instruments. In addition, the typology of responses deployed directly or indirectly mitigates risks by virtue of policy and planning initiatives, legal and regulatory systems, resourcing, capacity development, activation of institutional arrangements, stakeholder accountability, participation and engagement (see Figure 1). It is in view of these measures that the concept of risk governance continues to evolve shifting the discourse away from a government-dominated agenda to a shared responsibility where governance structures, markets and institutional networks are aligned to achieve collective goals (Hasselman 2017; Lange et al. 2013). Although the application of strategic responses and corresponding tactics to institutional processes have been recognised in various studies (Covaleski and Dirsmith 1988), its application to disaster risk management simulation and environmental sustainability studies have been noteworthy (Wijethilake et al. 2017; Toinpre 2020). Table 1 details the institutional response strategies and tactics.

Within DRR organisational fields, coordinating entities may often be inclined to instantaneously making strategic decisions in the best interest of the organisation and the jurisdiction where their statutory functions are undertaken. Hence, in deploying such response strategies it is ideally expected that stakeholder pressures to reduce risks should tend towards conformance. However, limited capacities, resources or awareness of pressures being exerted may result in resistance, which may translate to unsafe conditions that exacerbate vulnerability. Exploring actors and channels for response to pressures is therefore crucial.

Table 1: Typologies of strategic response to institutional processes.

Source: Oliver (1991)

Institutional actors and channels for DRR response

Governance is characterised by multiple and contextual actions, norms and behaviours of groups or individuals that simultaneously operate via formal or informal pathways (Renn et al. 2011; Renn 2014). Three categories of actors as identified by Lemos and Agrawal (2006) are:

- state actors (e.g. multilevel governance arrangements at national and sub-national levels)

- market actors (e.g. private sector)

- social actors (e.g. non-government organisations, community stakeholders).

Disaster risk governance entails bringing multiple actors together to solve complex issues and requires networks for seamless interoperability. Similarly, in instances where responses via emergency services (e.g. paramedics, police, firefighting services, public health organisations, military personnel) and community-based organisations are beyond the capacity of a country, international entities intervene (Perera et al. 2020). Global platforms through which some of these interventions have been developed are the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR), the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and International Risk Governance Council among others.

State actors are renowned for creating enabling collaborative mechanisms, which provide access to procedures and social services. These range from the establishment of technology, information, and communication channels to the design and development of critical infrastructure (Forino et al. 2015; Twigg 2015). DRR practitioners also aid the entire process of implementation (Forino et al. 2015). Market actors develop alliances and finance non-government organisations' campaigns to promote environmental wellbeing and responsible behaviour (Forino et al. 2015; Chadda and Kundal 2023). Corporate social responsibility can be achieved through philanthropy (e.g. donations), contractual (i.e. sponsorships to carryout work for public benefit) and unilateral agreements as well as under adversarial circumstances (i.e. lobbying and public statements on the environmental impact of operations). To address some of response-based challenges, public sector organisations may be required to respond by changing policy and legal frameworks, adopting new strategies or reviewing coordination arrangements (Patterson and Huitema 2019). Although, von Meding et al. (2013) classified response based on the nature of hazards, a fundamental issue still lies in the disjointed approaches to risk reduction. An example is the time-bound nature of rapid and slow-onset events (Moe and Pathranarakul 2006). For example, responding to slow-onset disasters such as gully erosion, famine or drought would require a different approach when compared to earthquakes, flash floods or tsunamis. A limited consideration of the timely nature of hazards and lessons learnt may indicate ineffective or delayed responses (Mude et al. 2009; Wassenhove 2006). However, it is beneficial for public sector organisations to recognise these disparities while mobilising channelling resources efficiently to reduce disaster risks.

Some response-based challenges in DRR organisational fields

Despite several efforts made by public sector organisations to reduce disaster risks, there are still barriers that hinder positive DRR organisational field outcomes (Birkmann et al. 2010; Krüger et al. 2015; Forino et al. 2018). Challenges which still impact on institutional responses in DRR include contested logics among institutional actors; fragmentation and complexity of global environmental governance (Bertels and Lawrence 2016; van Asselt 2014); integration of Indigenous knowledge, worldviews and inclusivity (Agrawal et al. 2022; Goerlandt et al. 2020) and diversifying risk communication methodologies (Pigeon 2013; Abunyewah et al. 2020). Such barriers may prevent cross-disciplinary dialogue for inclusive and collaborative DRR-focused initiatives (Djalante and Thomalla 2012; IPCC 2012). Formal and informal responses have been identified in the wake of the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami necessitating institutional reforms (Hettige and Haigh 2016; Birkmann et al. 2010). There is also the controversy between ‘response’ as a ‘scientific/technical’ issue and a ‘social construct’ that still lingers (Birkmann et al. 2010; Krüger et al. 2015). The technical responses are often broad-based and presents the public with minimal engagement and participation opportunities (i.e. GIS and other geo-spatial analysis for risk assessment) while institutional approaches are widely criticised for being politically driven arguing the dominance of policy-actors (Forino et al. 2018; Jerez-Ramírez and Pinzón-de-Hijar 2022). However, regardless of the typologies used, public sector organisation responses should be adaptive and focused on risk reduction and resilience building (Ahmed et al. 2020), which may include social capital, competence, economic development and communication for response, which thrives on local level leadership.

Methodology

Research philosophy and data search

This study used a qualitative research method underpinned by constructivist worldview where individuals or groups ascribe meanings to social problems (Creswell and Poth 2016). This approach involves the gathering of data by reviewing documents, books, journal articles or reports (Patton 2014). According to Creswell and Poth (2016), qualitative research is conducted to explore a problem or issue, which requires a complex detailed understanding. Although there are various opinions about the extent to which literature reviews can be conducted, qualitative texts are reviewed to provide a rationale for a problem and positions a researcher’s study within ongoing literature about the topic being discussed (Marshall and Rossman 2010; Creswell 2015).

Literature review was conducted in 3 stages using Google Scholar and other open-source platforms. These sources provide access to high quality peer-reviewed journals and reports published in English, which were retrieved, stored and organised using EndNote 20 software. Creswell and Poth (2016) suggest interpretive and theoretical frameworks to shape qualitative studies. This requires making assumptions, paradigms and presenting frameworks explicitly. The first stage was conducted prior to the study to examine theoretical underpinnings guiding the design of the framework (i.e. Pressure and Release model, Institutional theory and Strategic Response to Institutional Processes) as propounded by Wisner et al. (2014), DiMaggio and Powell (1983) and Oliver (1991), respectively. The second stage involved reviewing literature on institutional constituents and actor networks to identify key antecedent mechanisms and channels that facilitate response. The final stage involved the review of government reports, journal articles and conference papers to explore contextual applications of institutional responses to disaster risks and hazard events. These reviews formed the basis for the design and development of the framework guiding the study.

Approach to inquiry and analysis

As Yin (2009) suggests, case studies are suitable strategies for explanatory and descriptive studies. Other researchers agree that they are a suitable form of inquiry, design and a unit of analysis (Creswell and Creswell 2017). Creswell and Poth (2016) also state the use of multiple forms of data such as interviews, observations and documents rather than relying on a single source. The study is therefore based on an extensive literature review, primary data obtained from semi-structured interviews and textual analysis of observational findings from a 2-scenario tertiary-level disaster risk management education simulation-based learning activity conducted at the University of Newcastle, Australia. The simulation participants were assigned roles to depict relevant stakeholder groups within the DRR organisational field. The rationale for this inclusion was to explore how institutional pressures influences responses to flood risk conditions. However, for the purpose of this study, the unit of analysis was organisations and observational findings from the simulation-based learning scenarios where participating students represented communities, public sector organisations and international non-government organisations. A human research and ethics committee approved the data collection process for the selected case studies (number H-2018-0015). Social constructivism as an approach to inquiry involves the analysis of texts (Lincoln et al. 2011). Including textual analysis based on observations from a published peer-reviewed article was crucial to indicate the significance of multistakeholder dialogue in disaster risk governance. Observations from the scenarios were coded manually and the analysis of text aided the design and development of the framework.

Analysis and discussion

Analysing the IPRM framework

The IPRM framework provides a holistic view of the cyclic interactions between institutional pressures and responses that influence DRR outcomes (see Figure 1). In this instance, dynamic pressures (section A) are manifested through institutional structure constraints such as resourcing (i.e. skill-shortages, financing, risk transfer), which lead to dysfunctions in systems and processes (i.e. outmoded planning policies, building codes and land use legislation) ultimately undermining government efforts and local capacities. Where there are limited capacities, there are tendencies for progression of vulnerability to unsafe conditions such as fragile physical environments, which increases the levels of vulnerability and susceptibility to hazards. In instances where institutional constraints are persistent, institutional constituents (stakeholders) therefore exert pressures through expectations and demands for safer physical, social, economic and environmental conditions such as updated building codes and land use legislation and resilient infrastructure (section B).

Figure 1: The Institutional Pressure and Response Mechanism framework.

Isomorphic pressures are drivers of organisational growth, and they encourage competitive markets and propel organisational performance (DiMaggio and Powell 1983). However, the availability of resources, capacity, commitment and the awareness of the nature of pressures being exerted influences the ability for public sector organisations to perform. In any such instances, organisations are presented with the choice of responding using strategic options at their disposal, which may lead to conformance or resistance to mitigate risks (Section C). These forms of responses are often agency-driven and mainly spear-headed by constituents and decision-making entities. Depending on the strategic choices employed, public sector organisations would develop instruments (mainly process-driven) to foster actions aimed at addressing institutional constraints thereby responding to expectations and demands to enhance DRR outcomes (section D). For example, policy and planning initiatives are used as prescriptive tools and procedural guidelines to shape stakeholder behaviours. The legal and regulatory system reforms proffer updated guidelines, which other sectors have to comply with in order to foster public actions in alignment with statutory obligations. For example, existing policies and guidelines for flood risk governance in the Nigerian case study include the National Environmental (Wetlands, Riverbanks and Lake Shores) Regulations, S.I. No. 26 of 2009 and National Environmental (Soil Erosion and Flood Control) (National Emergency Management Agency [Nigeria] 2018). While some of the existing initiatives have been operationally critiqued, there are still avenues to consider updating existing frameworks and mechanisms. The World Bank’s National Erosion and Watershed Management Programme has played a key role in supporting and addressing some vulnerability gaps in partnership with some state governments. Based on the selected case study, participants reflected on mechanisms that facilitate responsiveness for risk reduction, which tend towards a conformance strategy. These included media intervention, international non-government intervention and political interest, as shown in Table 2.

Media intervention

The media plays a significant role in transmitting risk information to the public. Such information is necessary for participation and engagement in DRR initiatives as well as response activations and evacuations before, during and after hazards. The media also plays a key role in shaping community perceptions by building a culture of safety through awareness of risks and measures to address them. Some of such channels include social media (e.g. Facebook, X, Instagram, WhatsApp), television, radio, newspapers and SMS.

Why that issue was resolved speedily was because we went there and granted [a] press interview on national television and the interpretation was that […] was blaming government for what happened so immediately they swung into action…

(Public sector organisation R1)

The media was the second most cited response antecedent. Having been identified as a crucial mechanism for stimulating government responses especially in emergencies to provide information relevant for relief, identifying sources of physical, psychological, emotional or financial support. New York’s notification system Notify NYC 311 was used to provide information on emergencies, public health issues and school closures (Eugene et al. 2022). In Australia, the Fires-near-me, Emergency Plus, Bureau of Meteorology weather and hazards-near-me apps have been developed to inform stakeholders on appropriate warnings and preventive measures. The Queensland Remote Aboriginal Media has also been offering a similar service for boosting communication (Commonwealth of Australia 2022).

International non-governmental organisation intervention

International non-governmental organisations such as United Nations Development Programme and United Nations Environment Programme, United Nations Office for Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UN-OCHA), World Bank, Food and Agriculture Organization and the World Health Organization play crucial roles in strategic and operational responses through development programmes and humanitarian assistance. This antecedent factor was referenced 9 times from 3 sources. Often times, disasters overwhelm the capacity of communities whose resources are scarce and may find it challenging to respond effectively and efficiently given the complexities and uncertainties presented.

Funding can stimulate the ministry to work hard. The government also needs to collaborate more with international agencies; United Nations World Health Organization, you know they normally have grants they give to state governments to manage such risks.

(Public sector organisation R30)

In Australia, non-government organisations have been instrumental in managing service provision on behalf of the government. For instance, the Red Cross’s 'Register. Find. Reunite' and Making Cities Resilient campaign launched in 2010 by the UNDRR have been a useful avenue for encouraging effective international, transboundary and local governance for enhancing action, learning and cooperation.

Table: Response antecedents facilitating disaster risk reduction.

| Nodes | Sources | References |

| Media intervention | 8 | 10 |

| International NGO intervention | 3 | 9 |

| Political interest | 6 | 11 |

Political interest

Political interest was the most referenced response antecedent (referenced 11 times from 6 sources). This response antecedent plays a dominant role in the prioritisation of risks. This is often shaped by vested interests and availability of resources for investing in DRR. Furthermore, key issues such as DRR and climate change adaptation are often not considered as major government priorities due to the pressing need for critical infrastructure services such as bridges, roads, telecommunications, schools and hospitals in some countries. However, these are indirect initiatives for addressing risks, which need to integrate aspects of DRR. In addition, resource and capacity development interventions are crucial for enhancing DRR skills and competencies as well as funding mechanisms to implement statutory functions.

The most important thing is for the people that are leading us to have interest in disaster management. If they have interest, they will fund you to carry out your legitimate activities. But where they do not have interest, you will be talking to the wrong people because they do not see the need for all that.

(Public sector organisation R3)

Further, activating emergency and DRR institutional arrangements is crucial. This requires support from governments at national, regional and local levels. Operational responses are often activated by virtue of the strategic response choices and tactics employed by public sector organisations. Based on the observations during the simulation activities, which involved the assigning of roles, participants showed that due to the persistence of risks, communities, public sector organisations and international non-governmental organisations were more likely to experience all 3 forms of institutional pressures. We found that some participants exhibited some level of intuition and improvision while others did not deviate from the script (acquiescence). Participants representing public sector organisations demonstrated willingness to collaborate with communities advocating for a forward-thinking approach to risk reduction (compromise). While some participants did not articulate arguments in an authoritative or tactful manner (avoidance), others felt comfortable with their power positions, as it was daunting to manage multiple interests among stakeholder groups (defiance). On the other hand, some participants displayed domineering roles, which shaped the discourses (manipulation).

Mechanisms bridging DRR organisational field response: a practical context

Given the enormous challenges presented to public sector organisations involved in policy implementation, DRR and climate change policies require bridging governance mechanisms to facilitate multi-level implementation (Raikes et al. 2022). These include inter-organisational networks established for response and recovery categorised into inter-organisational network support, adaptive networking response and interconnected network support (Mutebi et al. 2022). Inter-organisational networks play a key role in facilitating adaptive processes of change, access and distribution of aid (i.e. supply chains) and organisational learning (Thomalla et al. 2006; Forino et al. 2015). Through inter-organisational networking in Bolivia, a shared risk analysis and participatory planning tool utilised by CARE, OXFAM and World Vision was developed to facilitate a collective development process to foster DRR and climate change adaptation initiatives (Srodecki 2011). These networks of interaction are valuable in reducing policy fragmentation, changing organisational cultures, increasing productivity, enhancing efficiency, reducing redundancy and cutting transaction costs (Ward et al. 2018).

Forino et al. (2015) identified 3 forms of partnerships that act as bridging mechanisms. These include public-private partnerships, private-social partnerships and co-management. Lassa (2012) also opined that such intergovernmental interactions in a post-disaster context is characterised by complexities, which have the propensity to trigger formation of new networks and clusters. These have been exemplified through post-disaster reconstruction and the emergence of humanitarian networks for multilevel communication and coordination (Mees et al. 2017). Public-private partnerships are partnerships between state and market actors and act as motivators of investment in DRR and recovery/reconstruction projects, which grapple with limited public financing (Lemos and Agrawal 2006; Forino et al. 2015). Public-private partnerships also aid the expansion of services beyond public sector organisation reach and improves efficiency, responsiveness and resource access (Chatterjee and Shaw 2015).

In response to climate change, Australia has developed a whole-of-economy plan to achieve net zero emissions by 2050 aligning with global commitments towards sustainability (Australian Government 2021; Gajendran et al. 2024). The Australian Government also designed institutional arrangements such as the National Climate Change Adaptation Framework, National Strategy for Disaster Resilience, National Disaster Risk Reduction Framework and Australian Government Crisis Management Framework to support this agenda. In partnership with the Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery, the Australian Government is ensuring World Bank investment in the Indo-Pacific region with a strong focus on risk financing and early action in response. An example of this is Australia’s response in the aftermath of the January 2022 Tonga volcanic eruption. Australia is working with UN women in Fiji, Vanuatu and Kiribati in the Pacific to ensure systems, plans and policies are gender-responsive to empower women in leading solutions for preparedness, prevention, response and recovery (Commonwealth of Australia 2022). Other examples of response-based activations include the establishment of the National Bushfire Recovery Agency in response to the summer bushfires in 2019–20 and the National Drought and North Queensland Flood Response and Recovery Agency in response to the Queensland floods in 2019 (Commonwealth of Australia 2020).

Conclusion and recommendation

In view of the several challenges hindering the efficacy of responsiveness towards the reduction of disaster risks, this study clearly identified some response-based challenges that can be categorised as sources of institutional pressures. DRR organisational networks are therefore subject to coercive, normative and mimetic pressures and prospective studies need to focus on exploring these pressures, response mechanisms to pressures and the concomitant influences of response typologies on DRR outcomes. Although, this has been exemplified illustratively using the IPRM framework, diversifying case study contexts and applications are crucial to holistically explore and ameliorate disaster risk concerns. The findings suggest that key response antecedents may include media intervention, political interest and international non-government organisation intervention. Furthermore, this paper discusses bridging mechanisms such as public-private partnerships, private-social partnerships and co-management that can be leveraged to facilitate responses for interoperability among DRR organisational field constituents in the study location with lessons learned from examples of best practice.

Although, response may be influenced by capacity and awareness of public sector organisations and communities to understand and act, there is need for diversifying communication channels, pedagogies or methodologies for training and retraining of personnel responsible for implementing functions. Conversely, the role of non-government organisations in emergency interventions and DRR cannot be overemphasised. Non-government organisations have over the years played significant roles in response, recovery and reconstruction through community-based disaster risk reduction initiatives, which has led to the conduct of trainings, workshops, community stakeholder meetings and other forms of engagement resulting in progressive outcomes and in raising substantial funds. However, our conceptual idea of the IPRM framework is to accelerate the DRR discourse in the context of recognising a more holistic view of responsiveness not just in the ‘response phase’ of the disaster management cycle, but within DRR organisational fields and particularly in pre and post disaster scenarios. This also includes harnessing and allocating resources required for efficiency of disaster risk governance mechanisms and arrangements and decision-making. Knowledge in this area is scarce and can be extended further to explore challenges and solutions to facilitate responsiveness considering other contexts.