Introduction

Mass stabbing attacks, while rare in Australia, are not unheard of. Enhanced counter-violence medicine coupled with creating a culture that values active bystanders as immediate responders, can help mitigate the effects and also deter such attacks from occurring in the first place.

The violent stabbing attack that occurred at a Sydney shopping centre on 13 April 2024 (Visontay et al. 2024), is one of the deadliest and most extensive mass stabbing (or any planned mass violence) recorded in Australia in decades. When it comes to understanding violent public attacks, the phenomenon of mass shootings in Australia is well-documented (Chapman et al. 2016). Historical data reveals a total of 14 mass shootings in Australia (McPhedran 2020). A significant number of these incidents, specifically 9, occurred in New South Wales. Notably, the vast majority of these shootings took place before major gun law reforms in 1996. From 1979 to 1996, Australia experienced 13 fatal mass shootings.

Paramedics at the Westfield shopping centre waiting to treat injured people.

Image: Helitak430, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

In stark contrast, in the period post-1996 reform, there has been only one incident (ABC News 2015).

The profiles of the perpetrators indicate that many experienced significant acute life stressors or ongoing difficulties prior to attacks, though a formal diagnosis of mental illness was not commonly recorded (McPhedran 2020). In comparison, less is known about mass stabbing incidents. These events are not as thoroughly chronicled as their shooting counterparts, particularly those not categorised as terrorist acts.

Using the Global Terrorism Database (GTD)1, there has been 6 documented terrorist attacks in Australia that involved knives as the primary weapon and occurrences spanned between 1981 and 2020 (see Table 1). These attacks targeted private citizens and property, with some attacks directed at business entities and police forces. All implicated perpetrators were motivated by Jihadi-inspired extremism. The attacks have led to 6 fatalities.

However, this data does not encompass non-terror-related stabbing incidents, such as that at the Westfield Shopping Centre in Sydney. This suggests a gap in the tracking and understanding of this type of violence. By examining previous studies, only one non-terror-related mass stabbing attack was identifiable in Australia prior to the Westfield attack (Amman et al. 2022).

Historically, knives and sharp objects have not been the most common weapon used in terror attacks in Australia. The terror attack that took place on 16 April 2024 at a church in Sydney against a bishop and a priest is the latest case (Turnbull and Atkinson 2024). Overall, the data on terrorist attacks in Australia indicates a predominant use of incendiary devices. These were used in approximately 70% of the recorded terror incidents. Firearms have been used in 13% of the attacks, while knives and other bladed weapons have been involved in 10%. Explosives, including bombs and dynamite, have been used in about 5% of the cases (Tin et al. 2021).

Public mass stabbings, much like shootings, require the perpetrator to be in close proximity to their victims. This proximity significantly reduces the likelihood that the attacker can escape arrest or avoid being fatally wounded during the intervention. Despite these operational similarities between stabbings and shootings, the strategies for countering them differ significantly due to the accessibility of the weapons involved. While firearms are generally regulated and harder to obtain, knives and other sharp objects are everyday tools, readily accessible and commonly found in households. This accessibility makes preventive policies challenging.

Internationally, the trends in violent acts against the public, particularly mass stabbings, reveal distinct patterns and motivations that vary significantly by region. Data show that the majority of mass stabbing attacks are carried out by lone, male offenders using knives. Notably, half of all documented mass stabbings have taken place in China (Amman et al. 2022).

Table 1: Evaluation data verification and coding.

| Date | City | Perpetrator group | Fatalities | Injured | Target type |

| 16/12/2020 | Brisbane | Jihadi-inspired extremists | 2 | 0 | Citizens and propertya |

| 9/11/2018 | Melbourne | Jihadi-inspired extremists | 2 | 2 | Police, citizens and propertyb |

| 9/02/2018 | Melbourne | Jihadi-inspired extremists | 0 | 1 | Citizens and propertyc |

| 7/04/2017 | Queanbeyan | Jihadi-inspired extremists | 1 | 0 | Businessd |

| 10/09/2016 | Minto | Jihadi-inspired extremists | 0 | 1 | Citizens and propertye |

| 23/09/2014 | Melbourne | Jihadi-inspired extremists | 1 | 2 | Policef |

a. www.couriermail.com.au/subscribe/news/1/?sourceCode=CMWEB_WRE170_a_GGLanddest=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.couriermail.com.au%2Fnews%2Fqueensland%2Fpolice-probe-whether-knife-used-by-rahge-abdi-linked-to-couple%2Fnews-story%2F8369ac8022ddb962f5edfad3fa2052b5andmemtype=anonymousandmode=premiumandv21=GROUPA-Segment-2-NOSCORE

b. www.reuters.com/article/idUSKCN1NE2M3/

c. www.theguardian.com/world/2018/feb/15/sister-of-bangladeshi-student-accused-of-melbourne-stabbing-arrested-in-dhaka#:~:text=Sister%20of%20Bangladeshi%20student%20accused%20of%20Melbourne%20stabbing%20arrested%20in%20Dhaka,-This%20article%20isandtext=The%20sister%20of%20a%20Bangladeshi,attacked%20officers%20with%20a%20knife

d. www.smh.com.au/national/nsw/service-station-worker-fatally-stabbed-in-queanbeyan-police-hunt-for-two-teenagers-20170407-gvfkat.html

e. www.abc.net.au/news/2016-11-24/terrorism-inspired-attacker-ihsas-khan-made-admissions/8054708

f. www.nytimes.com/2014/09/27/world/asia/isis-australia-mohammad-ali-baryalei.html

In terms of motivations, approximately a third of these attacks were reportedly linked to the perpetrator's mental illness. Interestingly, there is a marked correlation between the location of the attack and the attacker’s motive. Incidents driven by mental health issues have been disproportionately more likely to occur at educational institutions. Interestingly, the majority of attackers (90%) were not repeat offenders (Amman et al. 2022).

When examining the geographic patterns of mass violence, stark differences emerge between mass stabbings and mass shootings. Mass shootings are more prevalent in the United States, Russia, Yemen, the Philippines and Uganda. In contrast, mass stabbings occur predominantly in China Japan, Canada, India and Israel, with China accounting for more than half (and by some estimates, over 60%) of global cases (Silva 2023).

Other epidemiological characteristics that can be compared across the 2 forms of mass violence include:

- location of attacks – open areas are the most frequent sites of mass stabbings, contrasting with commercial locations for shootings

- survival of perpetrators – the survival rate of offenders diverges; 77% of stabbers survive the incidents compared to 42% of shooters who survive

- casualty figures – despite differences in modality and context, the number of casualties inflicted by mass stabbings and shootings are surprisingly similar, indicating that both forms of violence are effective at harming groups of people (Silva 2023).

While it may seem intuitive that China and the United States, 2 of the most populous countries in the world, report higher numbers of mass stabbings and shootings the disproportionality of these incidents relative to their populations is striking. Despite comprising less than 18% of the global population, China accounts for over 50% of the world's mass stabbing incidents. In China, where gun control laws are among the strictest in the world, the rarity of firearms may shift the means of mass attacks to weapons that are readily available.

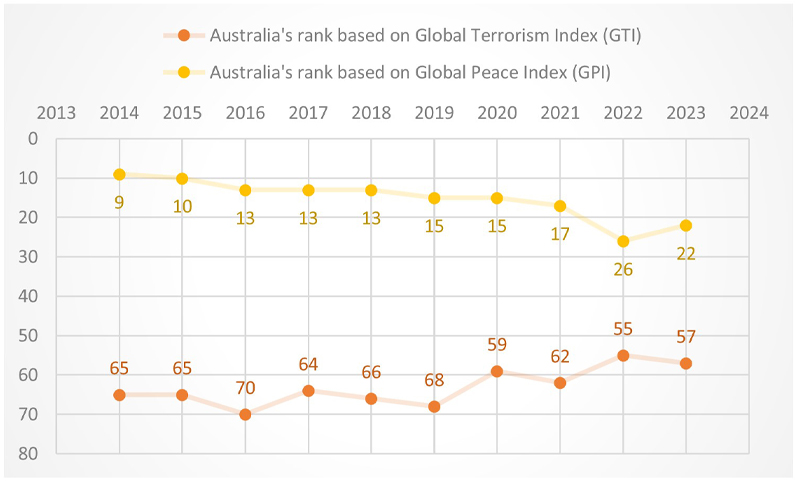

While mass stabbing attacks are a rarity in Australia, the evolving nature of global and domestic threats necessitates ongoing vigilance. In August 2024, the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation raised the terror threat level from ‘possible’ to ‘probable,’ marking the first such escalation in nearly a decade (Haghani and Spaaij 2024). The Global Peace Index (GPI)2 and the Global Terrorism Index (GTI)3 can also be used as barometers for assessing Australia's shifting security concerns and atmosphere over time.

Australia's 2023 GPI score was 1.52, positioning it 22nd globally (higher rankings indicate more favourable positions and safer conditions). This Index is composed of 23 indicators, ranging from perceived criminality in society, homicides, violent crime, jailed population, military expenditure to relations with neighbouring countries and levels of political instability. A tracing of this index over time reflects a slight shift to relatively unfavourable positions compared to a decade ago (Figure 1).

On the terrorism front, Australia currently ranks 57th based on its GTI 2023 score. The GTI assesses the effects of terrorism based on incidents, fatalities, injuries and the number of hostages taken. Similar to GPI, the GTI shows a slight worsening of Australia’s position from 65th a decade ago to 57th place (lower rankings indicate better conditions).

Figure 1 shows Australia’s trends on both these indices. Australia's slightly deteriorating scores in both the GPI and GTI over the past decade could potentially highlight the need for continued and fortified planning and policy adaptation to pre-empt and mitigate emerging and evolving public security threats.

The need for enhanced counter-violence medicine

Counter-Terrorism Medicine (Tin et al. 2021) is rapidly emerging as a critical sub-specialty, reflecting the need to enhance frontline responses to terrorist acts. This includes mass stabbings. The distinct and often more severe nature of injuries inflicted in terrorist stabbings compared to civilian incidents requires the development of specific medical protocols and training for trauma units (Merin et al. 2017).

There are significant differences in terms of trauma preparedness. Terrorist stabbings typically aim to inflict maximum harm, resulting in multiple victims with complex, severe injuries that can overwhelm standard emergency protocols. These incidents often result in simultaneous admissions of multiple patients with penetrating wounds, primarily to the upper body, which are life-threatening and require immediate and specialised care. In contrast, civilian stabbings usually involve fewer victims and less severe injuries, with a different pattern of wound locations, often in the abdominal area.

Figure 1: Australia’s changing GPI and GTI rankings in the world between 2014 and 2023.

The adaptation of trauma care protocols to better handle the unique challenges posed by terrorist stabbings is essential. This includes advanced surgical and medical treatment approaches as well as logistical considerations to efficiently manage the high influx of patients during mass casualty incidents.

The potential role of ‘active bystanders’

Bystanders also play a role in the immediate aftermath of public violent incidents. These individuals can be considered part of the emergency response team, as ‘zero responders’ (Haghani 2024; Haghani et al. 2023) or ‘immediate responders’ (Haghani et al. 2023). These proactive individuals can be pivotal in bridging the gaps before emergency services arrive on the scene. Their quick actions, whether by reporting the incident, confronting the attacker, providing first aid or managing crowd movement, can significantly mitigate the negative effects of the attack.

In cases like the Sydney attack, active bystander interventions proved to be lifesaving. By using impromptu barriers to slow the attacker, providing immediate medical assistance or guiding others to safety, these individuals did more than witness; they actively shaped the outcome of the crisis.

Integrating ‘zero responders’ into emergency preparedness and response can dramatically enhance societal security. Societies benefit immensely when they acknowledge and prepare their citizens to act in crisis situations. Training and supporting zero responders can be considered a key enabler in national security policies.

Different cultures and countries exhibit varying approaches towards zero responders. For example, Israel's Good Samaritan Law (Ashkenazi and Hunt 2019) protects active bystanders from civil liability, compelling them to assist in emergencies and potentially offering compensation for any resultant costs or injuries. Similar provisions exist in Australian law to protect people who assist others who are injured, ill or in danger, although there are differences in legislation across the states and territories.4

Statistically, the presence of more zero responders during an emergency correlates with higher survival rates. While not everyone can be trained for such roles due to willingness or capability issues, research suggests that not all community members need comprehensive training to significantly enhance emergency response outcomes (Haghani and Sarvi 2019; Haghani and Yazdani 2024).

While the role of zero responders is crucial to mitigate the effects of mass violence, it is essential to carefully consider the potential physical and psychological risks they face. The integration of civilians into emergency response should be promoted with these considerations in mind (Australian Red Cross 2024). Active involvement in emergencies can lead to injury or trauma and, without proper training, people’s actions might inadvertently exacerbate the situation. Therefore, it is important to provide structured guidance at a societal level, along with support and recognition, to ensure that zero responders are adequately prepared and protected. Being a zero responder does not mean confronting a hostile attacker or risking lives. An immediate bystander response can take many forms, including identifying a threat at an early stage and alerting fellow citizens or authorities, guiding people to safety, facilitating an evacuation or delivering first aid.

An example is the incident in New York City in 2010 where street vendors in Times Square (ABC News 2010) noticed a suspicious vehicle emitting smoke. Their quick report to authorities led to the discovery and defusing of a car bomb, potentially saving many lives. Preventing terrorist attacks is not solely the responsibility of the public. Businesses and private security providers also play a critical role. High-traffic venues like sports arenas, concert halls and shopping malls can be prime targets for terrorism (Haghani 2024). The vigilance of security personnel, adjusted to the level of existing threats, adds an important layer of protection. A notable example is Richard Jewell (Ishak 2023), a security guard at the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta. Jewell’s keen observation of an unattended backpack, which turned out to contain a bomb, and his prompt action in notifying authorities and assisting in evacuations, ultimately saved many lives.

Unlike other disaster events, the threat of terrorism is dynamic and heavily influenced by our level of preparedness. The likelihood of an attack, particularly on public venues is intricately linked to the perceived robustness of security measures and the overall readiness of society (Australian Government 2018). An aggressor's decision to target a specific venue is shaped by the security posture of the location, which informs their assessment of the likelihood of success or failure of the attack. Being better prepared by strengthening counterterrorism medicine and fostering a culture of vigilant active bystanders and zero responders can significantly enhance collective resilience against such threats and potentially deter them.