Globally, the frequency and magnitude of weather-related hazards poses significant challenges for governments and the private and the not-for-profit sectors. This paper provides exploratory insight into the challenges that hinder institutional responses to risk reduction. This study specifically considered public sector organisations within disaster risk reduction (DRR) organisational fields. The paper identifies 3 major constraints, which include fragmentation, difficulties in using risk information and cultural identities that affect public sector organisations and community responses. To analyse these issues, an institutional theory lens was used to explain the antecedents under which institutional actors may respond based on events and stakeholder expectations and demands. The findings suggest that challenges hindering response to risks and emergencies are strategic, institutional or operational in nature. A selection of public sector organisations response initiatives is presented within an Australian context with analysis of the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2023 Priority 4. Recommendations and further research to identify and address other institutional constraints and sectors are recommended.

Background

Globally, the frequency and magnitude of hazards arising from climate change pose significant challenges for governments and the private and the not-for-profit sectors. Australia has had its fair share of floods, bushfires, earthquakes, cyclones and drought and the role of the public sector in responding to emergencies and reduce disaster risks is vitally important. This is because public sector organisations are significant institutional pillars that guide societal actions. Public sector organisation functions include substantial investment in critical and social infrastructure, regulatory enforcement and providing channels for collective public action including education, training and communication (Wilkinson 2012; Twigg 2015; Abunyewah et al. 2020). Australia’s second National Action Plan (Commonwealth of Australia 2023) for the implementation of the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2023 (the Sendai Framework) (UNDRR 2015) indicates that the complexities associated with climate change, emergency management and risk governance architecture often makes coordination efforts difficult. Other institutional challenges associated with risk prioritisation, public awareness and engagement as well as social vulnerabilities (Paton 2019; Paton and Buergelt 2019) have been identified.

Given the complexities and uncertainties associated with risk reduction and response, this paper uses a 2-stage literature review to identify institutional challenges that influence public sector organisations and community responses as well institutional theory concepts associated with disaster risk governance. To enhance institutional responses, government reports were analysed to identify response-based interventions from an Australian perspective. The Sendai Framework Priority 4 was deconstructed as a prescriptive guide to simplify rudiments for enhancing disaster preparedness for effective response pre- and post-disaster.

Methodological approach: data search, screening and synthesis

The use of a qualitative method as a mode of inquiry into the meaning individuals or groups ascribe to social problems is one akin to research involving constructivism and the use of theoretical lenses (Creswell and Poth 2016). It involves the collection of data through examining documents, observing behaviours, interviewing participants or reviewing literature using books, journal articles and reports (Creswell and Poth 2016). This study involved traditional and critical literature reviews, which explored institutional response challenges and interventions in pre- and post-disaster stages. The rationale was to provide theoretical underpinnings that explain the antecedent factors that may influence response.

Document analysis is a valuable approach that has been underused (Merriam and Tisdell 2016). Document analysis of government reports was conducted to understand how response in Australia has been approached. The rationale was to integrate aspects of authoritative and credible sources that were peer reviewed and based on a royal commission inquiry into past disaster events including consensus contributions and agreements among government entities and stakeholders. Guiding the document analysis was the intent to identify response-based initiatives and interventions that have shaped the emergency management discourse in Australia. As Australia is a signatory to the Sendai Framework (Paton 2019), Priority 4 was deconstructed to develop a conceptual framework for public sector organisations responses.

Scopus and Google Scholar were used to obtain quality and credible peer reviewed papers published in English. A phrase-specific search on Google Scholar used the search string ‘institutional challenges hindering response to disaster risks and emergencies’ to identify common barriers of public sector organisation response outcomes. An initial search generated 142 documents, which were filtered based on title, abstract, keywords, body text and relevance to the discourse. There were 8 duplicates that were removed using Endnote software and 37 documents were inaccessible. This left 97 documents for scrutiny. In addition, an internet search using Google yielded 25 documents from Australian governments on the Australian Institute for Disaster Resilience Knowledge Hub, the National Emergency Management Agency website and other open source platforms.

Table 1: Some response-based challenges in DRR organisational fields.

| Contexts | Response constraints | Authors |

| Contested logics across disciplines. Environmental policies and power dynamics. Complexities of competing demands and expectations. |

Fragmentation | Bertels and Lawrence 2016; Kissinger et al. (2021); Hagelsteen and Becker (2019) |

| Influence of risk communications on intentions to prepare. Relationships between municipal risk communication approaches and development priorities. Design and implementation of early warning systems. |

Information access | Abunyewah et al. (2020); Agrawal et al. (2022); Goerlandt et al. (2020); Satizabal et al. (2022) |

| Indigenous knowledge, worldviews and inclusivity. Risk, transformation and adaptation. Design and implementation of disaster management interventions. |

Cultural identities | Ali et al. (2021); Paton and Buergelt (2019); Paton (2019); Cannon (2016); Imperiale and Vanclay (2020) |

Response-based challenges within DRR organisational fields

The term ‘institution’ has been widely used in disciplines to mean different things. According to Scott (2013), the generally accepted view is that institutions are social structures characterised by a high level of resilience comprising of cultural-cognitive, normative and regulative elements that provide meaning to social life. Disasters often necessitate institutional reforms and a shift in the manner with which communities manage or respond to risks. These shifts may take the form of creating new ways of adapting or responding to disasters or even totally transforming the social, economic or environmental aspects of a community. Marlowe and Lou (2013) identified a 2-way response approach (community-based and public sector-based response) to the magnitude 7.1 earthquake of September 2010 in Christchurch, New Zealand. Community members from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds shared valuable information for mobilising community members and organisations to identify safe shelters amidst other challenges of limited linguistic competencies, social capital networks and the awareness of local hazards (Ward et al. 2018; Marlowe et al. 2022). Table 1 provides some context to the response-based challenges in DRR organisational fields.

Fragmented nature of DRR organisational fields

In DRR organisational fields, teams are drawn from diverse disciplines and bring together personnel with varying backgrounds, experiences and skillsets. Challenges can arise from limited shared understanding of how issues may be assessed and resolved (Renn et al. 2011). This issue is attributed to mindsets and views of fields as fragmented with contesting logics, which influence organisational actions (Bertels and Lawrence 2016; Lounsbury 2007). Given the variance in standards of operations, the manner with which personnel execute plans would differ, which leads to information asymmetry and operational or evaluative disconnects under field conditions. Twigg (2015) suggested that partnering organisations may have different mandates, value systems and ideologies as well as funding streams and may use and interpret terminologies differently. During coordination, organisations are required to make decisions under high degrees of uncertainty and in complex situations due to competing demands from multiple stakeholders. This could lead to ambiguity (Hagelsteen and Becker 2019). Kissinger et al. (2021) also identify fragmentation as a challenge in the environmental policy area indicating conflicting sector goals, disconnects between global and local action and ambition as well as imbalances in power dynamics.

Access to information difficult to use

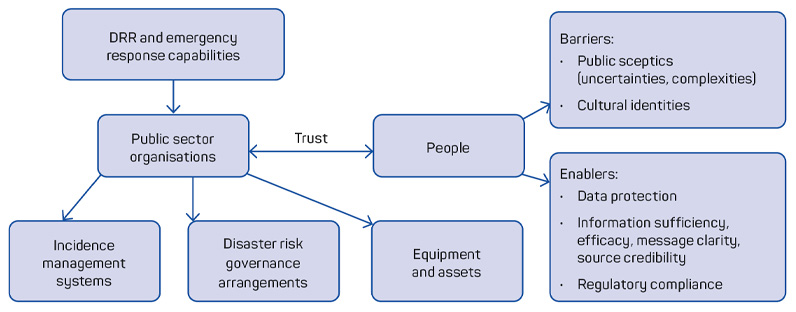

Communication plays a crucial role in organisations as it sets the pace for decision-making and organisational or community actions. It also has a central role in managing disaster risks. The challenge is that communication can take a one-way dimension (mostly in a scientific or quantifiable manner). Hence, it can be difficult to simplify information for diverse populations with varying learning and interpretative needs. DRR personnel also deal with multiple channels of communication to improve responsiveness. A challenge is to identify ways to minimise language barriers for tourists and residents (Teo et al. 2019; Véliz-Ojeda et al. 2020) who may have limited understanding of the dominant language in communities where they dwell. As such, public sector organisations must develop mechanisms through symbols or language translations that can be integrated into information sharing platforms. Abunyewah et al. (2020) suggested that elements of effective risk communication such as trust, information sufficiency, efficacy, message clarity and source credibility are crucial for a community’s participation and receptiveness (see Figure 1). The literature review indicates that for knowledge to be effectively created and disseminated, the transformation or conversion of tacit and explicit knowledge should be considered (Toinpre et al. 2018; UNDRR 2015; Twigg 2015). While this may be a daunting task, communities can use dialogical approaches involving cross-cultural communication mechanisms.

Cultural identities impeding risk management

Culture plays a critical role in risk management and influences the manner with which societies perceive and respond to disaster events. People interpret information differently based on their cultural identity manifested through lived experiences, beliefs, traditions, geographic location and gender orientation (Hewitt 2009; Lai 2022; Odiase et al. 2020). This means cultural aspects would determine the choices people make to adapt, avoid or cope with a particular situation. Culture shapes people’s perceptions and responses to a given event (Hewit 2009). For example, response would differ for people residing in mountainous regions experiencing volcanic eruptions or glacial activity compared to people residing in riverine areas experiencing flooding (Bird et al. 2011). This implies that geographic location also influences people’s risk knowledge and behaviours. According to Blaikie et al. (2014), the lack of access to power, structures and resources exacerbates vulnerability and unsafe conditions. Therefore, understanding power positions and the influence on responses to risks is crucial. Also, the representation of vulnerable communities and their inclusion in critical and social infrastructure (i.e. schools, hospitals, recreational spaces, bridges, etc.) investment is of paramount significance (Tierney 2012). Political will to address this can influence wealth distribution and risk reduction investment in exposed communities. While people living in communities with access to amenities and resources are better able to relocate to safer locations, others living in areas with minimal investment in critical infrastructure may find it challenging to safely relocate. Another consideration is that of trust, loyalty and sense of attachment to the land. Hewitt (2009) described this as a dilemma between remaining as ‘environmental refugees’ and ‘perceptions of safety’.

Figure 1: Institutional antecedents for disaster risk reduction and response.

Institutional pressures and antecedents for public sector organisation responses

Understanding institutions and how they work is beneficial to identifying response mechanisms that address stakeholder expectations and demands to reduce risks within communities. The lack of organisational analysis presents a challenge to DRR organisational field actors especially for those involved in designing and implementing projects, informing policy dialogue and coordinating development efforts across various levels of governance. For example, in the wake of the summer bushfires 2019–20, some states responded by declaring a state of emergency (Commonwealth of Australia 2020). Table 2 lists examples of events that activated institutional and operational responses to DRR in Australia.

Public sector organisations are subject to 3 forms of institutional pressures (coercive, normative and mimetic) both internally and externally. Coercive pressures manifest through an organisation’s adoption of practices or processes prescribed by a dominant organisation. Normative pressures stem from meeting requirements such as certifications, protocols and standards of operations. Mimetic pressures involve imitating organisational processes or practices that have proven to be successful (DiMaggio and Powell 1983; Scott 2013; Toinpre et al. 2018). Various stakeholder groups, including public sector organisations officials, and the public can exert these pressures. Table 3 categorises some institutional responses to constraints based on event-triggered activations listed in Table 2.

Exploring antecedent factors through which public sector organisations respond to pressures provides a rationale to analyse organisational behaviour under varying circumstances (Oliver 1991). The willingness and commitment of organisations to conform or resist coercive, normative or mimetic pressures depends on:

- why the pressures are being exerted (cause)

- what entities are that exert the pressures (constituents)

- what sort of pressures are being exerted (content)

- where the pressures are emanating from (context)

- by what means the pressures are being exerted (control).

An understanding of these conditions may assist public services organisations effectively respond to disaster risks under varying conditions. These antecedents often shape DRR and emergency response capabilities.

Table 2: Examples of response-based activations in Australia 2003–2019.

| Events | Year | Response initiatives / activations |

| Bushfires in the Australian Capital Territory | 2003 | Restructured emergency management arrangements Developed a Strategic Bushfire Management Plan (SBMP) |

| Indian Ocean tsunami | 2004 | Quad partnerships between Australia, the United States, Japan and India |

| Tropical Cyclone Oswald | 2013 | Betterment funding under Category D |

| North and Far North Queensland monsoon trough | 2019 | |

| 2019-20 bushfire season | 2019 | National Bushfire Recovery Agency Queensland State of Emergency New South Wales State of Emergency |

| [Merge with above] | 2020 | Victoria State of Disaster Australian Capital Territory State of Alert |

| Queensland flooding | 2019 | National Drought and North Queensland Flood Response and Recovery Agency |

| Tropical Cyclone Kirrily | 2024 | Disaster Recovery Funding Arrangements1 |

| COVID-19 pandemic | 2019 | Partners in the Blue Pacific – an initiative between Australia, Japan, New Zealand, United Kingdom and the United States of America |

Source: Commonwealth of Australia (2020)

Table 3: Categorising some institutional responses to pressures emanating from constraints.

| Institutional constraints | Coercive | Normative | Mimetic |

| Fragmentation | Political commitment | Institutional efficiency | Inter-organisational collaboration |

| Information access | Public sector financing | Information sharing and engagement | Externally institutionalised norms |

| Cultural identities | Regulations | Attitudinal change | Adopting new practices |

Exploring Australia’s institutional responses to DRR

Australia’s DRR organisational field has experienced change. In 2023, the National Emergency Management Agency (NEMA) was established through a merger between the previous National Recovery and Resilience Agency and Emergency Management Australia. This change came with the need for organisational advisory support so that decision-makers are provided with the necessary tools, equipment/assets to respond to demands and expectations from institutional constituents while ensuring incident management systems and governance arrangements are inclusive. As identified in the mid-term review of the Sendai Framework implementation, Australia has agencies and committees such as the Australia-New Zealand Emergency Management Committee2 and Australia and New Zealand Council for Fire and Emergency Services (AFAC)3 to meet its obligations to improve resilience of communities (Commonwealth of Australia 2022). Figure 2 provides examples of multilevel institutional frameworks that complement existing arrangements between Australia’s states, territories and local governments.

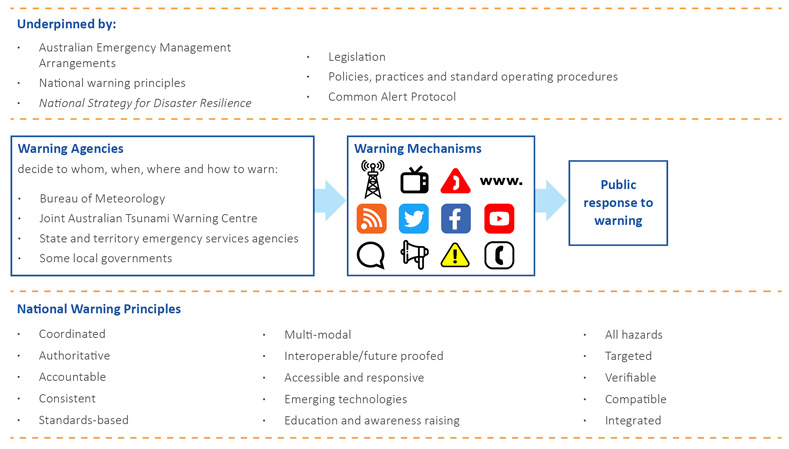

Various organisations deal with fragmentation differently. For example, homogenising the National Recovery and Resilience Agency and Emergency Management Australia to establish NEMA has unified operations in terms of reducing duplication and improving coordination and management of emergencies and disasters. However, the challenge remains in synergising operations across disciplines within the field. Using an inter- and intra-organisational approach through the formation of collaborative partnerships such as the Northern Rivers Resilience Initiative4 (a partnership between NEMA and CSIRO in New South Wales) has prioritised flood resilience through the development of a community-supported solution (see Figure 3 for Australia’s early warning arrangements). Another initiative to address fragmentation has been the Regional Collaborations Program5 that builds linkages in the Indo-Pacific Region to facilitate research and innovation.

Figure 2: Examples of multi-level institutional frameworks and arrangements for DRR in Australia.

Source: Adapted from Commonwealth of Australia (2020), p.112.

Figure 3: Australia’s emergency warning arrangements.

Source: Commonwealth of Australia (2020), p.289.

In terms of access to information, the Australian Institute for Disaster Resilience Knowledge Hub supports and informs policy, planning, decision-making and contemporary practice in risk resilience. Another initiative is the Trusted Information Sharing Network6 that works with industry on critical infrastructure resilience. AFAC is also a trusted source of advice for the field through sharing knowledge, lessons learnt and challenges. Finally, considering the issue of integrating cultural inclusivity into resilience initiatives, the Australian Government through the National Indigenous Australian Agency7 funds the Indigenous Ranger Program8 and Indigenous Protected Areas Program9 to support Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples to combine their knowledge with conservation training to protect land, sea and culture including cultural fire management activities. Other initiatives are Aboriginal Communities Emergency Management Program and the Australian Institute for Disaster Resilience Education for Young People Program10 to improve preparedness and response at a community level.

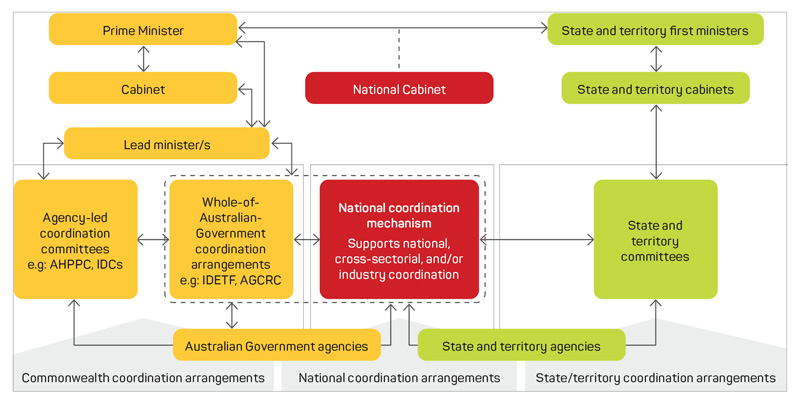

DRR efforts often depend on complex governance arrangements (Tierney 2012). The regulative and normative institutional pillars are based on defining institutional norms that guide emergency management policies and DRR strategies, plans and program implementation. However, in the Australian context, there are attributes that define emergency management systems that include existing arrangements, hierarchies, symbolic systems, routines and artefacts (Rosell and Saz-Carranza 2020; Albris et al. 2020) for national coordination (see Figure 2). There are 3 mechanisms that facilitate a whole-of-government approach; the National Coordination Mechanism, the Crisis and Recovery Committee and the Inter-Departmental Emergency Taskforce. These mechanisms provide situational awareness, advice and data to support decision-making, communication and strategic coordination (Figure 4).

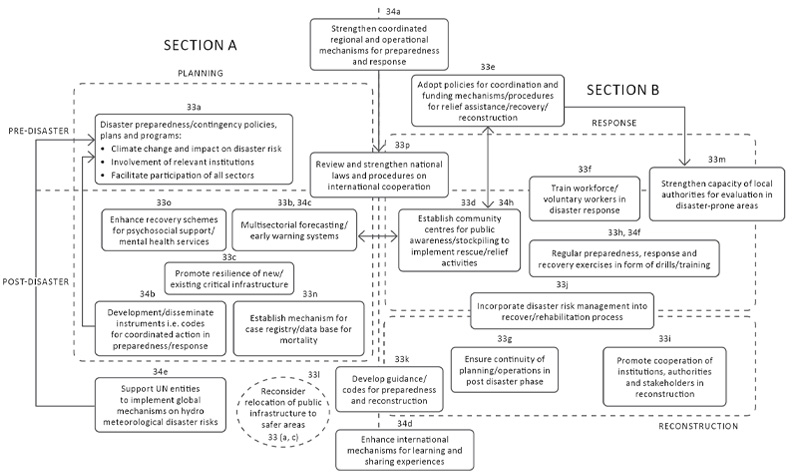

Institutional responses to disaster risk: integrating the Sendai Framework priority

Dealing with each phase of the emergency management cycle presents intra- and inter-organisational challenges that require experience and the right skills and competencies (von Meding et al. 2011; Ahmed and Charlesworth 2015; Seddiky et al. 2020). Responding to pressures may manifest through policy reforms, investment in critical infrastructure, capability enhancement through education and training or review of pre-existing institutional arrangements. The Sendai Framework Priority 4 - Enhancing disaster preparedness for effective response and to build back better in recovery, rehabilitation and reconstruction, emphasises the need to strengthen preparedness for response and taking action to anticipate while ensuring capacities are in place at all levels. Figure 5 shows that Priority 4 is sectioned across pre- and post-disaster actions to include planning (Section A) and response (Section B). Planning involves disaster preparedness policies and plans that include climate change and impact involving relevant institutions required to facilitate DRR participation and engagement. Response deals with harnessing human resources to facilitate participation and engagement. Multi-sector forecasting and early warning (33b, 34c) were identified as stimulants for investment in critical infrastructure (33c) especially those relevant for community evacuation. In addition, the development of codes for coordinated action in response and preparedness (34b) were noted as significant aspects to strengthen laws and procedures on national and international cooperation (33p). These will further yield initiatives for response involving the adoption of policies for coordination and funding mechanisms for relief assistance and recovery/reconstruction (33e). Priority 4 also emphasises on training and enhancing capabilities for response and recovery. This involves conducting drills (33h, 34f), simulations and stockpiling (33d, 34h) to aid rescue and recovery and to strengthen the capacity of local authorities for evacuation. By engaging community stakeholders, public sector organisations can bring continuity of planning and operations (33g) to the post-disaster phase.

This study was not exhaustive; however, it illustrates paths through which the Sendai Framework can be visualised. As public sector organisations responses may be either passive or active, Norman et al. (2014) suggest that, generally, such responses need to be continuously updated to reflect the latest scientific and technical knowledge. This is viable to help decision-makers within DRR organisational fields to consider areas given less attention. Traditions, beliefs and risk perceptions can determine community willingness and capacity to influence response in reconstruction and recovery (as was the case of Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Christchurch, New Zealand). Although in the case of Mostar, the concept of ‘building back better’ after a disaster did not override the role of cultural awareness and heritage preservation as they demonstrated a strong sense of place and cultural identity. For them, reconstructing a bridge and retaining its initial features using the same local materials symbolised the restoration of desecrated values and the re-established a structure of cultural significance.

Figure 4: Australia’s emergency management coordination arrangements.

Source: Commonwealth of Australia (2023), p.31.

Conclusions and recommendations

This study considered challenges that hinder response to risks and emergencies that are strategic, institutional and operational. Responses can be passive or active depending on the nature of antecedents. These aspects are often guided by the nature of pressures (coercive, normative or mimetic) exerted on institutional constituents. The study drew on relationships between institutional theory concepts and aspects of public sector organisation responses to understand institutional dynamics within DRR organisational fields. Given the complexities and uncertainties of disasters, DRR organisational fields are often multi-disciplinary and offer opportunities for different disciplines to work together. Yet, a fundamental challenge to unifying unique elements of varying logics, perspectives and values remains daunting across preparedness, prevention, response, mitigation, reconstruction and recovery. Effective responses are often characterised by trust, information sufficiency, efficacy, message clarity and source credibility. While risk information may be transmitted differently, diversifying information sharing is viable to foster multi-stakeholder responses. In addition, cultural identity issues manifest in difficulties associated with stakeholder characteristics, normative and cultural-cognitive attributes, varying values, cultures and traditions that influence community and organisational response.

Figure 5: Deconstructing the Sendai Framework Priority 4 - Enhancing disaster preparedness for effective response and to build back better in recovery, rehabilitation and reconstruction.

Practical steps that can be taken to bridge institutional gaps are provided in the literature. However, these appear scarce in DRR organisational field discourse using institutional theory. Practically, face-to-face communication by field workers, community mobilisers, extension workers, local meetings and workshops have proven to be effective for knowledge sharing, learning and dialogue that facilitate response. In Australia, constitutional and operational responsibility lies with the states and territories and the autonomous nature of risk management across jurisdictions differs making operationalising arrangements complex. The Royal Commission into Natural Disaster Arrangements (2020) detailed stakeholder challenges associated with understanding and using information. This causes inefficiencies, siloing and duplication of effort and calls for nationally consistent multi-hazard mechanisms for communicating risks. This approach helps to avoid confusion for states and territories using similar mechanisms but conveying different information across each jurisdiction. These gaps are being addressed. For example, the Australian Warning System11 was updated to bring consistency to actions for multi-hazard warning levels. These were the same nationally but had varying symbols and corresponding actions required under each alert level. This issue was also similar for terminologies used for fire danger ratings. Power dynamics is a major factor influencing actions and may emerge from socio-economic status of participating organisations, formal authority, social capital, specialist knowledge and expertise. Efficient accountability mechanisms may resolve some of these issues and propel receptiveness towards adopting practices that are more inclusive and holistic. A limitation of this paper is that it focuses on public sector organisations. Further contributions using other sectors will improve the knowledge base within DRR organisational fields.