Emergency management in Australia is undergoing a process of professionalisation. Those who undertake roles in emergency management are often seeking to be recognised as a professional. To support this process of professionalisation, research into the human capacities of the Australian emergency manager was undertaken. Emerging from that research was the concept of disciplines. It was found that discipline-based thinking when applied to the work of those within the field of emergency management provided a way to describe and explore differences in tasks and roles undertaken. Emerging from this analysis was the Emergency Management Disciplinary Spectrum. The Emergency Management Disciplinary Spectrum demonstrates how application of the concepts of discipline, multidisciplinarity, interdisciplinarity and transdisciplinarity can support the previously defined roles of Response Manager, Recovery Manager and Emergency Manager. The Emergency Management Disciplinary Spectrum provides a model from which to explore the development of future emergency management practitioners and professionalisation of emergency management in Australia.

Introduction

Emergency events are increasingly affecting Australian communities. For example, the Australian Institute for Disaster Resilience (AIDR) Major Incidents Report (AIDR 2017, p.3) noted 9 major incidents in 2016–17 but noted 30 major incidents in the 2023–24 report (AIDR 2024, p.1). These emergency events affect individuals and the environment in disparate ways. People may be injured or killed and communities may lose people-based capability (e.g. emergency responders), cohesion or vital assets. Additionally, the environment may be damaged and take a long time to recover if it does at all. Communities increasingly expect that those who have roles to prevent or prepare for emergency events, or those who lead response or recovery operations have more knowledge, skills and abilities so that they can prevent, reduce or ameliorate the effects of the emergency on individuals, the community and the environment.

Emergency management in Australia is undergoing a process of professionalisation (Dippy 2022, p.72). Professionalisation of emergency management requires that a range of activities are undertaken that include the development of a body of knowledge that can be applied consistently to emergency events (Yam 2004, p.979). The sources of the knowledge required by the emergency manager originate from a broad range of topics. Increasingly, knowledge is sourced from other occupations and is applied to the emergency event in unique and specific ways. Components added to the education of the emergency manager are taken from sectors including agriculture, business services, community services, property services, forestry, health, information and communications, local government, water, public sector management, sport and fitness, tourism, training and education, maritime and transport and logistics (Commonwealth of Australia 2018, pp.73–79). The number of packages that support the education of the emergency manager recognises and contributes to the breadth of skills applied across emergency management. The sources of the knowledge required to manage emergency events may be referred to as a ‘discipline’, for example the discipline of law or the discipline of mental health. It is the application of knowledge arising from those multiple disciplines that is required to manage an emergency event. This paper explores the effects of discipline-based thinking on the management of emergency events.

Background

Research was conducted to determine the human capacities of the emergency manager in Australia. In developing an understanding of human capacities, the concept of disciplines, and more broadly multiple disciplines, arose. The concept of disciplines explains the sources and application of the knowledge and skills underpinning the human capacities of the emergency manager. The emergency manager is the person who leads aspects of the mitigation of, preparation for, response to or recovery from an emergency event.

Emergency management is not yet recognised as a profession in Australia. Dippy (2020, 2022) summarised the requirements for emergency management to be recognised as a profession with reference to the work of Flexner (2001) and Yam (2004). Professionalism requires, among other attributes, an underpinning body of knowledge. The sources of the human capacities and underpinning knowledge applied while managing emergency events arise from different occupations, knowledge areas or themes. While some of the human capacities identified in the research arise directly from previous emergency events, others have developed from existing knowledge areas or occupations.

When existing knowledge areas or occupations are taught within a tertiary environment, they are often referred to as disciplines (e.g. the discipline of medicine or law). By applying disciplines to the exploration of the human capacities of the emergency manager in Australia, a conceptualisation of the development of the individual is formed that can support the evolution of a person into and within emergency management roles. By applying multi-disciplinary thinking to the sources of the information, it supports development of the emergency management body of knowledge and, thus, the professionalisation of emergency management.

This research builds on previous work by Dippy (2025) who defined the roles of the Emergency Manager, Response Manager and Recovery Manager as an outcome of the analysis of the human capacities of previously undefined emergency manager. The analysis that led to these 3 new definitions is continued with this further analysis of the human capacities emerging from his research.

Research methodology

The research question examined was ‘What human capacity demands should inform the development and appointment of an emergency manager?’ To address this question, 20 years of emergency event inquiry reports that had been subject to judicial or semi-judicial inquiries dated between 1997 and 2017 were examined. This 20-year range was selected because many contemporary emergency management principles were in place from 1997. Before this contemporary period of emergency management practice, the response to emergencies was based on cold-war-era civil defence paradigms (Emergency Management Australia (EMA) 1993, p.3). This included military-based command-and-control systems and a focus on nuclear emergency events.

Since 1997 there has been considerable change with the introduction of the AIIMS (AFAC 2017) and similar incident management systems for police and biosecurity agencies (ANZPAA 2012; Department of Agriculture Fisheries and Forestry 2012) as well as the National Strategy for Disaster Resilience (Commonwealth of Australia 2011) and the National Emergency Risk Assessment Guidelines (National Emergency Management Committee 2010).

Judicial inquiries are those that occur in a legal environment such as Coroners or criminal courts. Semi-judicial inquiries are those where there is enforceable, but outside of a formal court environment, requirements to provide information or answer questions. For this research, semi-judicial inquiries were those with a legislative requirement to answer questions such as a royal commission or another formal inquiry piece of legislation. Judicial and semi-judicial inquiries are only conducted for emergency events that have significant consequences for communities, based in part on the complexity or aftermath. The inquiry reports identified a range of human capacities of the emergency manager. Interviews were conducted with authors of 8 emergency event inquiry reports to uncover other human capacities required by the emergency manager.

The literature review examined broader management concepts in conjunction with the emergency event inquiry reports. The analysis of both theoretical and practical literature distilled and showed themes of the human capacities identified. Targeted interviews with 8 emergency event inquiry authors were analysed and themed together with the literature and emergency event inquiry reports. The interviews provided a broader range of human capacities from which to examine the role of the emergency manager.

A Gadamerian philosophical hermeneutic research methodology was applied to this work (Gadamer 2004, 2013; van Manen 1997). The interviews of emergency event inquiry authors and the examination of the emergency event inquiry reports generated over 15,000 pages of text. Further text was added for analysis from the literature review. The Gadamerian philosophical hermeneutic methodology acknowledges and incorporates the researcher’s participation in the field being studied to the analysis of the text being analysed. By rigorously recognising the researcher’s world view (Gadamer 2004, p.xi; van Manen 1997, p.197) through the Gadamerian processes of documenting, reflection and reconsideration, changes are captured and acknowledged. The application of Gadamer’s analysis methodology allows rigorous and replicable findings to emerge from the research.

This paper presents the concept and application of disciplines that arose from analysis of the literature as well as emergency event inquiry reports and interviews. The application of disciplines allowed analysis of identified human capacities. Discipline thinking applied to the human capacities allowed a model to be developed about how human capacities work together in managing emergency events. The model, the Emergency Management Disciplinary Spectrum, was used as a base to develop people who take on leadership roles in emergency events.

Ethics

This research was approved by the Charles Stuart University Human Research Ethics Committee, approval number H19294.

Findings – the Emergency Management Disciplinary Spectrum

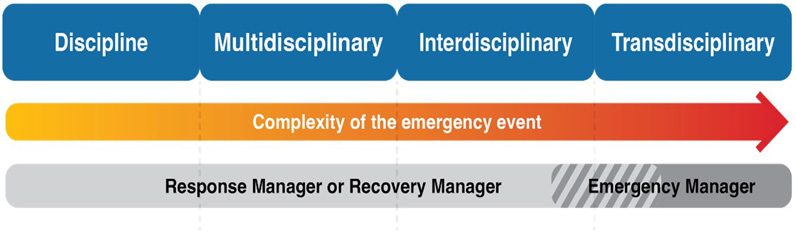

The Emergency Management Disciplinary Spectrum represents the identification of disciplines within emergency management and how those disciplines interact with the human capacities of the defined Emergency Manager, Response Manager and Recovery Manager (Dippy 2025). The concepts of disciplinarity, multidisciplinarity, interdisciplinarity and transdisciplinarity form the basis of the spectrum. To reduce confusion in the application of these concepts, the Emergency Management Disciplinary Spectrum demonstrates the application of disciplines in support of the work of the Response Manager, Recovery Manager and Emergency Manager.

Figure 1: The Emergency Management Disciplinary Spectrum.

Figure 1 illustrates the Emergency Management Disciplinary Spectrum and shows the disciplinary concepts applied alongside emergency management events from the simplest to the most complex. The disciplinary concepts are then aligned with the respective role to which they apply; that is, the roles of Response Manager, Recovery Manager or Emergency Manager.

The Emergency Management Disciplinary Spectrum was developed during this research and places the aspects of disciplines applied by the Response Manager, Recovery Manager and Emergency Manager into a simple model. The model shows that the Response Manager and Recovery Manager may operate across a single discipline, for example, firefighting or recovery. They may also work in a multidisciplinary arrangement with other disciplines such as police. Alternatively, they may use their skills in an interdisciplinary manner; for example, assisting an ambulance crew to extract a person from a location at height. The model acknowledges that there is overlap with the transdisciplinary aspect, in that the Response Manager and Recovery Manager may undertake some tasks that align with those of the Emergency Manager by undertaking ancillary transdisciplinary activities; for example, support for prevention activities.

The Response Manager and Recovery Manager are likely to have developed their initial skills in one discipline; for example, they may have started as a police officer or a social worker. Over time they have developed their skills in that discipline. The Response Manager and Recovery Manager may have lead aspects of their work; perhaps having moved to supervisory or managerial positions in their workplace. As their level of knowledge and expertise develops, it is also likely that the Response Manager and Recovery Manager will start to work with others in organisations, including the other organisations’ response managers and recovery managers. By this time the Response Manager or Recovery Manager is developing knowledge to work in a multidisciplinary manner. As the human capacities of the Response Manager and Recovery Manager develop it is likely that they will work with other agencies in an interdisciplinary manner. Working together may commence with joint training or exercising opportunities or may occur at an emergency event.

The Emergency Manager role has aspects of both interdisciplinarity and transdisciplinarity. They may be undertaking the interdisciplinary action of bringing multiple agencies together in support of a lead or control agency. Predominantly, the Emergency Manager will be undertaking the transdisciplinary actions to operate across prevention, preparedness, response and recovery and have a large component of working with the community in undertaking their duties.

Discussion - application of disciplines in emergency management

Interdisciplinarity emerged in this research as a human capacity descriptor for how the Emergency Manager, the Response Manager and Recovery Manager undertake their roles. While interdisciplinarity as a term was raised in one interview, when analysed, the underlying elements arose in all 8 interviews.

To explore and understand interdisciplinarity it is necessary to examine the disciplines that contribute to emergency management. The root of the word ‘interdisciplinarity’ is discipline, an academically used term for a branch of learning (Macquarie Dictionary 2023). Most people commence a professional career in one discipline or area of study and then branch out to other areas. The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) reported in February 2023 that 35% of recognised professionals in Australia had been in their job for between one and 4 years, with only 10% of those remaining in their job for more than 20 years. The ABS (2023) reported that 9.5% of all employed people in Australia had changed jobs during the preceding year (i.e. 2022). Baum (2022) noted that younger workers may have at least 7 jobs in the first 10 years of their career. For example, many people who study law do not go on to become a practicing lawyer but apply the acquired skills in other occupational areas.

The Emergency Manager, Response Manager and Recovery Manager demonstrate a similar career mobility in that many may have an initial job such as an operational firefighter, a police officer or a community development specialist. Over time, that initial role or job changes and the person may become an emergency manager, response manager or recovery manager often in addition to the original role in which they commenced employment. For the purposes of this discussion, based on the branch of learning definition of a discipline, each function is described as a discipline. For example, the function of operational firefighting (which has firefighters undertake a dedicated course of learning) can be considered a discipline as is the function of operational policing. These existing functions (or disciplines) may co-exist with other functions (or disciplines) such as being an Emergency Manager, Response Manager or Recovery Manager. Co-existence of multiple functions in the work of an individual is an initial example of a person undertaking multidisciplinary work.

A discipline has a set of knowledge, skills, behaviours, training (or education) and outcomes that are unique to that discipline. The operational firefighter has knowledge, skills and behaviours that are mostly different to the operational police officer. For examples of discipline-specific knowledge, skills and behaviours see Ahn and Cox (2016), Bruce et al. (2022) and Jones (2009). In this research, the terms ‘knowledge’, ‘skills’ and ‘behaviours’ encapsulate the individual human capacities of the Emergency Manager, Response Manager and Recovery Manager.

While human capacities may be shared across disciplines, the exact combination and application of human capacities shape the recognisable discipline. As a community, people are comfortable with the well-recognised disciplines of medicine, nursing and engineering and how those disciplines have developed to be recognised as a profession. Similarly, emergency management functions have human capacities. Emergency management applies different combinations of human capacities depending on the task being undertaken. For example, the human capacities of an Emergency Manager working in the application of building codes during the prevention phase may include the ability to understand and interpret complex law. Conversely, a Recovery Manager working with affected communities after may require human capacities that support psychosocial responses to traumatic events.

Medicine and law are recognised as both disciplines and professions. The recognition of medicine and law as professions is reinforced by the legal protections applied to the use of the terms ‘medical practitioner’ and ‘lawyer’ (see the Health Practitioner Regulation National Law (South Australia) Act 20101 and other Australian state and territory equivalents). Emergency management is not yet recognised as a profession. There is no legal protection of the term ‘emergency manager’ in Australian law.

Many disciplines require a tertiary education program for entry to the profession. For example, medicine and law both require tertiary education for entry to the field. To support this, education programs for professions are referred to as disciplines in the tertiary education context (Macquarie Dictionary 2023). Emergency management does not require a tertiary education for entry.

Many emergency management practitioners undertake vocational training or apply experience built over time to enter the field. Multiple vocational institutions use the term ‘discipline’ when describing their training programs. However, using ‘discipline’ by vocational institutions appears to be based on a dictionary definition, for example ‘a branch of learning’ (Macquarie Dictionary 2023) rather than a formal alignment with a recognised profession. While emergency management may be a training or educational discipline, it is not a recognised profession with a tertiary educational discipline label applied in educational contexts.

The community recognises the outputs of many disciplines. Medicine and nursing have well-known outputs including lives saved after a traumatic event or injury and less well-known outputs such as public health preventative outcomes including food safety, disease tracking and disease prevention. Emergency management has similar known and less well-known outcomes. For example, firefighters respond to fires, but they also contribute to improving building codes and fire prevention through compliance testing and education programs. Police have well-known outputs in the arrest of people suspected of having committed a crime, but less well-known outcomes in crime prevention, management and coordination of emergency events and road accident reduction.

As a person develops in a discipline, their knowledge, skills, behaviours and expertise are expected to improve. The time taken for improvements in knowledge, skills and behaviours will vary between individuals. As this occurs, it could be expected that their outputs as a factor of both quantity or complexity of work will also increase. It may be that with increasing expertise comes a change in roles from team member to supervisor, to manager. The increasing level of activity arises from increased knowledge of the role leads to an increased depth of overall knowledge. Increasing expertise can take a short or long period of time and that time is influenced by the volunteer or career nature of the involvement, training and education undertaken and experience gained. Some of this increase in expertise comes from formal and organisationally required education undertaken by the individual. Some is done by self-development that the individual undertakes in their own time and some by attendance at emergency events.

While this research demonstrated that career or volunteer status should not affect the selection of emergency managers, response managers or recovery managers, the nature of paid employment allows more time to be devoted to skills and knowledge development, which may accelerate skills acquisition. Conversely, skills development periods may be reduced for a volunteer (or career staff member) arriving with an existing selection of skills from a previous career or volunteer experience or education. For example, an ambulance volunteer becoming a police officer will obtain first-aid practical skills that are directly transferable to policing. In addition, communication skills from working with injured and sick people from various backgrounds are also directly transferable to policing roles.

Nicolescu (2014, p.187) stated that multidisciplinarity is the use of more than one discipline. Thus, a multidisciplinary emergency event is one where more than one emergency service provider attends. A vehicle collision could be considered a multidisciplinary event as the disciplines of ambulance, fire and police are all likely to attend. This multi-agency attendance could arise from a single or a multi-vehicle collision and the number of attending disciplines is based on the skills required at the scene, not the number of patients or vehicles.

While the vehicle collision emergency event analogy is a simplified example, the reality of emergency events is considerably more complex. The analogy provides an agency-by-agency example—that is, police attend to undertake policing and the fire service to undertake firefighting. The previous discussions recognising that people have multidisciplinary skills means that emergency events have the potential to be much more complex. Referring to the example of the ambulance volunteer becoming a police officer, their attendance at a vehicle collision could be considered to address the requirements of both a police and ambulance discipline to attend. There is also the complicating factor that some skills are common across disciplines. For example, both police and fire officers are trained in first aid, albeit not to the level of ambulance service members attending the emergency.

To simplify the discussion for the application of disciplines, this paper refers to an individual discipline such as police and fire in these examples. Continuing the simplified emergency event analogy (i.e. without considering that individuals may have multiple disciplinary skill sets) to include different disciplines, interdisciplinarity is where the skills of one discipline are applied to another discipline’s area of work. This event may arise where police are searching an area of scrub and require assistance cutting down trees and bush. In this scenario, a rural fire service, which has members with chainsaw skills, might attend. As this is not a fire event, the fire service would not be using their skills for its core business of firefighting but is applying its discipline-based skills in another discipline (police crime scene) environment. Another example of interdisciplinarity is the application of police traffic management skills at a bushfire event. In these examples, the skills of one discipline are applied to support another discipline’s core business event. The application of skills from one discipline to another illustrates interdisciplinarity.

Up to this point, the discussion of disciplines has been applied to the response of an emergency service agency and the ‘normal’ or core business services that they provide (e.g. a police agency and its role delivering operational policing services or a rural fire agency responding to a bushfire). Emergency events are becoming more complex, with compounding and cascading emergency events increasing in number and severity (AIDR 2024, p.22).

This discussion of disciplines has included the actions of an individual in an agency who is most likely to hold a role delivering the core business services of that agency, such as a firefighter undertaking firefighting duties. As a person develops further skills in an agency their role may change. Those changes may lead to them undertake additional roles as Emergency Manager, Response Manager or Recovery Manager (Dippy 2025). It is to this new or additional role of Emergency Manager, Response Manager or Recovery Manager that the concept of transdisciplinarity is applied and discussed.

Augsburg (2014, p.243) described a transdisciplinary individual as having 4 dimensions:

a) ‘an appreciation of an array of skills, characteristics, and personality traits aligned with a transdisciplinary attitude

b) acceptance of the idea that transdisciplinary individuals are intellectual risk takers and institutional transgressors

c) insights into the nuances of transdisciplinary practice and attendant virtues

d) a respect for the role of creative inquiry, cultural diversity, and cultural relativism.’

Nicolescu described transdisciplinarity as applying methods within, across and outside the individual disciplines (Nicolescu 2014, p.187). Transdisciplinarity includes aspects of multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary action. When considering McGregor’s (2014, p.201) definition that includes removal of boundaries, Mittelstrass’s (2011, p.336) application of transdisciplinarity in either a practical or theoretical sense and Von Wehrden et al.’s (2019, p.876 ) inclusion of academic and non-academic, the application of transdisciplinarity to an emergency is complex. The clarifying literature on this is Jahn et al.’s (2012) work showing that transdisciplinarity is an extension of interdisciplinarity. Jahn et al. (2012) stated that transdisciplinarity includes the community in the provision of the service. Coupled with this is Mittelstrass’s (2018, p.711) recognition that transdisciplinarity occurs when interdisciplinary actions become a permanent feature of the work. An example of moving from interdisciplinary work to transdisciplinary work is moving from the role of operational fire officer to an emergency manager, response manager or recovery manager, where the work entails ongoing linkages with the community.

Returning to emergency event analogies, an interdisciplinary emergency is a complex event where multiple response organisations must provide their skills in the emergency. This could be a major bushfire where each attending organisation is required to provide specific discipline-based skills. In the bushfire scenario, the fire service/s (a discipline) apply firefighting skills to the suppression and control of the fire. The police service (another discipline) applies traffic management, evacuation and emergency management coordination skills. The fire service exercises control of the event with that control extending to include brigades of its own as well as other fire agencies such as metropolitan or forestry brigades.

For the major bushfire example, the Australian-defined terms of command-and-control are deliberately applied due to their broad use in incident management systems. ‘Command’ is the internal management of resources in an agency (AIDR 2023a). Command is described to operate up and down in the agency structure. ‘Control’ is the external management of other agencies at an emergency event (AIDR 2023b) and is described to operate horizontally, from agency to agency, normally by interaction at the agency-lead person level.

Fire service control at the major bushfire also extends across spontaneous resources such as farmer-supplied fire units and other agencies such as police, ambulance, local government, non-government (e.g. the Red Cross) and other entities. For this example, the fire service appoints an incident controller (AIDR 2023), a role included in the defined Response Manager (Dippy 2025, p.68). The person exercising control of the major bushfire, the Response Manager (or incident controller in this example) works within, across and outside (Nicolescu 2014, p.187) their own agency skill set, and within emergency services and the rest of the world (McGregor 2014, p.201). This requires a practical and theoretical (Mittelstrass 2011, p.336) understanding of the capabilities of all of the agencies responding to the emergency event.

What takes this bushfire example from interdisciplinarity to transdisciplinarity is the interaction with the community. For an interdisciplinary event, the management will be provided by the fire service to the community. For a transdisciplinary event, the management will be provided by the fire service with the community. The transdisciplinary transition of management may be demonstrated when local knowledge is sought, integrated and applied. There is likely to be an embedded role in the incident management team incorporating local knowledge to the management of the emergency. For example, see Recommendation 14 of the 2009 Victorian Bushfires Royal Commission final report (Vol. 2) (Teague et al. 2010, p.90) for a discussion on the application of local knowledge.

Another example of transdisciplinary within the bushfire event is the integration and coordination of farm fire units provided by community members (normally farmers). In this case, emergency services organisations are working with the community and are not doing things to the community. Several of the reviewed inquiry reports identified that the coordination of farm fire units was a gap in the response (Schapel 2008, p.241; Teague et al. 2010, p.102). The farm fire units were not integrated into response activities and their actions did not align with and build on the actions of the responding fire services. The movement from doing to, to doing with the community (as raised by these inquiry reports) is the same issue discussed by interviewee 5 (pp.29–30). If the mindset of the Response Manager or Recovery Manager can be changed from one of interdisciplinarity to one of transdisciplinarity, the outcomes are improved.

The Emergency Manager undertakes a range of roles in the prevention, preparedness, response and recovery aspects of an emergency. They are also operating within, across and outside (Nicolescu 2014, p.187) their own agency skill sets, and within emergency services and the rest of the world (McGregor 2014, p.201). They require a practical and theoretical (Mittelstrass 2011, p.336) knowledge of plans, capabilities and capacities of all of stakeholders. However, the Emergency Manager works with the community to achieve the required outcomes. Working with the community is what differentiates their role from interdisciplinarity—the work of the Emergency Manager is transdisciplinary.

Noting the interviews conducted for this research, that the best outcomes are achieved by emergency managers, response managers and recovery managers applying the transdisciplinary approach to emergency events, the work of Augsburg (2014) supports the examination of what is required from a transdisciplinary individual via the 4 dimensions listed previously.

Interviews conducted for this research sought, in part, examples of human capacities that lead to an effective and appropriate response to emergency events as well as examples of human capacities that may be missing during a response. Re-analysing the interview transcripts considering Augsburg’s (2014) dimensions of a transdisciplinary individual included comments such as:

…someone who has an inquiring mind, who is able to clearly articulate strategy, clearly articulate what his or her expectations might be, and to commence that dialogue.

(Interview 1)

…the ones that understand that there are interconnections between every aspect of life.

(Interview 5)

I think he was also someone very committed to the standard operating procedures, and without some of the adroitness that you could see from the responders on the ground, that understood the need to quote ‘throw the rule book out.

(Interview 2)

…the ability to engage with risk and make the decisions with very limited information, limited ability to validate, and very, very compressed time frames.

(Interview 7)

The interviewees broadly described human capacities observed at, or missing from, an emergency event. During the interview, they were not able to use the defined terms of ‘Emergency Manager’, ‘Response Manager’ or ‘Recovery Manager’ in their responses as it was their descriptions that led to these roles being defined. The interviewees identified human capacities that align with Augsburg’s (2014) transdisciplinary individual dimension (a), in that aspects of an inquiring mind, articulation of strategy, interconnections, adroitness and engagement with risk are an array of skills, or human capacities, align with a transdisciplinary attitude. The interviewees were identifying the need for the Emergency Manager, Response Manager and Recovery Manager role to be transdisciplinary.