Introduction

‘Place’ is an unequivocal aspect of people’s experiences of disaster. From phenomena such as ‘topophilia’ marking people’s love of place (Barton 2017) and ‘solastalgia’ capturing one’s sorrow of its destruction (Barton 2017), processes that shine a light on rehabilitating places to build resilience and prepare for disasters are critical. These highly sensory and environmental experiences of disaster strongly relate to First Nations perspectives on connecting with Country and offer a decolonised view of space as inherently linked to time (Smith 2012); a process and not only an outcome (Massey 2012). Such ways of thinking about place supports and accelerates the movement towards place-based programs and community-led processes.

Government, not-for-profit and philanthropic organisations in Australia are increasingly turning to place-based approaches, acknowledging that a collaborative and community-led focus can generate shared understandings that can unlock systemic issues. Place-based programs and initiatives recognise that communities are often best placed to understand their unique local needs. To do this, they facilitate community participation methods to tackle challenges, including entrenched disadvantage and compounding disasters. Programs such as Stronger Places, Stronger People (Geatches et al. 2023), The Nexus Centre (Geatches et al. 2023) and First Nations community-controlled health care initiatives such as those funded by the Lowitja Institute (2024) highlight a burgeoning national place-based reform agenda. In the same vein, the Paul Ramsay Foundation developed diverse place-based resilience-building programs since the 2019–20 summer bushfires such as Fire to Flourish.1 Geatches et al. (2023) point out that such approaches are fundamental to self-determination of First Nations peoples and that this way of working has immense potential to reimagine top-down relationships that have historically created barriers for communities with differing needs. Thus, new opportunities arise for community-led approaches.

With many design, participatory and built environment disciplines naturally working in place-based ways, ‘placemaking’ (Hamdi 2010; Projects for Public Spaces n.d.) and similar ‘co-design’ (McKercher 2020) methods have emerged with the potential to offer innovative pathways that can shift inflexible structures and models. When melded with creative practice, First Nations leadership and research, place-making offers a compelling tool to activate place-based resilience initiatives.

Placemaking on Yaegl Country (Woombah) in 2023.

Image: Yuk Chun (Amy) Kwong

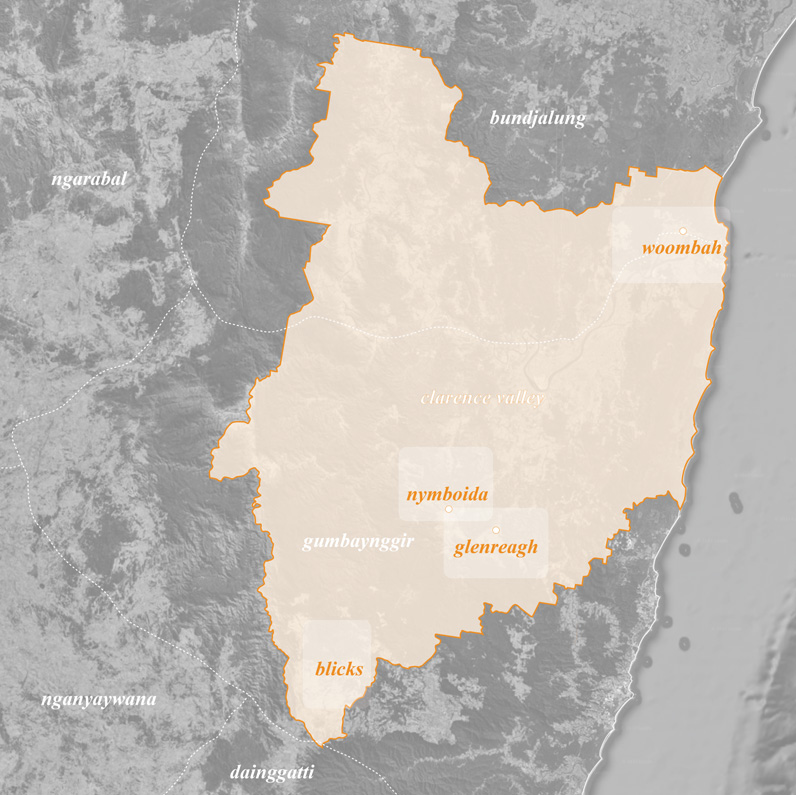

The Placemaking Clarence Valley program (Monash University 2024), a key piece of action research within Fire to Flourish, put such an approach into practice. It is composed of a local community team, design researchers and a group of architecture and urban planning postgraduate students in a novel collaboration. The program was formed to support a group of communities with diverse resilience ideas, many increasing in need following the 2019–20 bushfires. Over 2023–24, 4 localities situated across Bundjalung, Gumbaynggirr and Yaegl Country (Figure 1) came together to generate rich ideas for new or upgraded spaces. This included places and concurrent services that worked in concert across multiple modes for everyday social resilience as well as during emergencies. Doing so revealed that placemaking is a highly relational process that activates participatory principles in place-based settings. It supports community resilience planning through a socially engaged process of co-creating ideas for places as well as through built and infrastructural outcomes generated from that process.

Figure 1: Map of Bundjalung, Gumbaynggirr and Yaegl Country and the Clarence Valley Local Government Area on the northern New South Wales coastline.

The community leaders, creative practitioners and researchers who led the program shared 5 learnings that have emerged from the program. These learnings capture anecdotes and evidence of how creative placemaking enhances resilience. However, what was also revealed was the existing barriers to developing robust opportunities to augment such ways of working within the disaster and resilience sector.

Discussing ‘place’ explicitly brings people together

First Nations peoples and communities have known and practised the importance of connection to each other and Country (place) for many generations. This connection has been intrinsically linked to their health, wellbeing, resilience and the ability to prosper. First Nations scholar and educator, Marion Kickett, defined resilience in First Nations communities as:

The ability to have a connection and belonging to one's land, family and culture, therefore an identity. Allowing pain and suffering caused from adversities to heal. Having a dreaming, where the past is brought to the present and the present and the past are taken into the future. A strong spirit that confronts and conquers racism and oppression, strengthening the spirit. The ability not just to survive but to thrive in today's dominant culture.Usher et al. (2021)

Wiradjuri/Ngemba woman, Roxanne Smith, initiated Placemaking Clarence Valley to provide a vehicle that enabled communities of diverse backgrounds to come together, dream of the future and link their lives with the places, spaces and Country they live in.

Exploring needs, connection points and access for services, entertainment and culture highlighted those links and in doing so, broke down many barriers. People’s resistance to ‘dreaming’ dissipated and in turn created a series of connection cogs that helped progress and incite action in the dreams that resonated across the community. The creative and visual practices that focused on the community members' places encouraged even the biggest cynics to eventually ‘jump in the ring’. They wanted to highlight their knowledge, their connection to their places and share dreams about their Country, they wanted to be engaged! They could see this was about them and a better future for all, it was visual, it was physical, it was connected and heartfelt. It had a purpose!

Smith (2024)

Smith’s (2024) observations highlight that people, places, services, systems and Country are interconnected in reciprocal overlapping relationships and resilience can be amplified when groups of people interact and collaborate effectively in a physical context. Although proximity and relationship with physical ‘place’ are what enable people to self-organise and solve problems in a crisis, we cannot extricate the physical aspects of place from a more complicated and dynamic set of social relationships and practices.

Time is critical to place-based initiatives

For researchers and practitioners to gain valuable insights, the importance of exploring a locality, meeting people, visiting homes and experiencing ‘problems’ in real time cannot be overstressed. To truly understand a place, however, can take a lifetime; ‘enough’ time is always an issue.

People from the 4 localities in this program consistently erred away from using the placemaking program to resolve the consequences of recurrent bushfires or vast systemic problems in their areas. This was likely due to insufficient time and that there wasn’t holistic expertise to do so. Rather, people attended with the intention to join a facilitated discussion with fellow community members on how to prepare for a next time, to better help themselves and others, in the context of improving shared places.

To augment this shared understanding and to grapple with the tension of time, the team provided a methodology and creative place-oriented tools to consider next best steps. Specifically, the time barrier was ‘hacked’ by using long-standing relationships the community leaders and extended teams on the ground already had with local people. These pre-existing, deep levels of trust enabled this novel process to emerge powerfully in each context within a relatively short period of time. Thus, despite many of the postgraduate students not fully grasping the underlying rural mindset, social boundaries and, at times, language, they were able to support in effective ways.

Key contributions included synthesising community-led findings into a collective vision and key action projects housed within strategic placemaking frameworks that galvanised well-informed project proposals derived from each locality. Additionally, creative renderings and spatial drawings of proposed solutions to problems, needs and undeveloped potential of sites fast-tracked thinking during the 14-month period of the program.

Supported by seed funding, the prevailing mood was steady and hopeful that meaningful improvements could be made in due course. Critically, projects were catalysed by various creative tools and outcomes designed to assist with decision-making after the research was over.

Creative practices transform how resilience is framed

The program experimented with creative, community-led approaches to build disaster resilience. Rather than focusing on ever-present risks and emergency response, processes considered community needs and priorities during the ‘good’ times too.

Gathering in communal spaces, the team used walking, photography, drawing, mapping with tactile materials, listening to Elders on Country and participating in First Nations-led ‘yarning’ to involve people from each locality. People were invited to reflect on their locality's social, natural and cultural assets, including built infrastructure. This holistic thinking, combined with placemaking approaches, enabled participants to leverage local knowledge, identify strengths, enhance adaptability to one another’s ideas and promote forms of social cohesion that are valuable day-to-day let alone in times of crisis.

Accompanying the hands-on placemaking tools was action research designed to contribute to a growing body of evidence on the high social impact of creative recovery approaches (Creative Recovery Network 2023). Importantly, action research provided tangible resources for involved communities (Monash University 2024). Local data, photos, maps, quotes, results of surveys and ballots were presented in accessible formats within placemaking frameworks. These resources facilitated community and stakeholder engagement with a shelf-life well beyond the program’s duration.

Technical barriers inhibit resilience building: placemaking processes help

Place-based initiatives often rely on technical skills to augment the ways in which community-led insights influence resilience building. From discrete processes such as mapping, transposition of paper-based data, grant writing and digital tasks to technical activities such as developing feasibility studies or concept designs, significant challenges exist for communities to take next steps (Cavaye 2001), even when funding is available. This program experimented with how partnerships can bridge these gaps through knowledge and skills sharing. Leveraging the skills of postgraduate students and practice-based researchers bolstered the involved communities by offering technical inputs that might normally require expensive consultancies. An example was the implementation of online and in-person voting systems for community-led decision-making processes.

Good participation rates were achieved through providing participants with highly visual information along with both digital and paper-based voting platforms. In some instances, participation was 32%. Such outcomes show there is still room to improve participation in community-led decision-making but that nuanced systems coupled with technical support can generate strong insights. Additionally, supporting community development with approaches like ‘service learning’ (involving students) can disrupt volunteer fatigue and pro bono consultancy arrangements, which can often lead to a deprioritisation of projects due to personal and financial loads on individuals and organisations.

Successful resilience-building processes depend on ‘deep context’

Smith (2012) indicates that data and research are ‘dirty words’ in many remote and regional communities, particularly those with high populations of First Nations peoples. However, when derived from the ground up and governed in a self-determined way, research can be a powerful asset for local groups to lead their resilience-building initiatives. The program generated various forms of local data that helped groups develop and justify a collective case for change. Discrete research activities were fortified with creatively driven community engagement in parallel with involvement by members of the local council. This meant that diverse touchpoints with the program were available to stakeholders. This also assisted in building momentum towards community-led grants processes culminating in each locality.

An example of how local data informed the research design were the surveys developed and distributed by the leadership team. Surveys were designed in digital and paper formats and were available on social media platforms and at community locations. Surveys used plain language: what were people’s places of interest, how could they be improved and what needs to be protected? Responses identified places of interest that informed the research team’s site and context analysis and placemaking workshop design.

The survey piqued interest in the research and a total of 127 people attended the workshops. A community exhibition of outcomes from the workshops, coupled with feedback forms, allowed participants to explore the survey findings some months later and to see the visualisations of design possibilities along with ways to offer critique. The culminating community-led granting resulted in nearly 400 votes for a range of project applications across the 4 localities and formed the community-led decisions around what was ultimately granted.

The gradual uptick in engagement confirmed the viability of the projects in terms of community needs. Since various projects required planning approvals from local councils, the aggregated community consensus gave councils the confidence to support projects and to participate in the program. To assist in mobilising projects, the local council offered several rounds of regulatory advice along with waiving planning fees so that projects could hit the ground running.

Conclusion

The Placemaking Clarence Valley program experimented with how creative and participatory forms of data generation and community-led research can transform into an engaging and reciprocal process. While focused on place and improvements to physical infrastructure, the process enabled a set of social relationships and practices to emerge. Although there were limitations in the scale of participation reach and breadth, reflections on the learnings provide answers for how creative participatory processes can work better, articulated through a set of emerging principles. Beginning with local people, an acknowledgment of the value of spending time in place together is intrinsic to First Nations peoples’ wellbeing and develops the critical ingredient of relationality, that ultimately, all can benefit from. Using arts, cultural and creative practices to co-design new infrastructure and services provides opportunities to develop meaningful and ongoing discussions and to share knowledge and collaborate. While gathering evidence and evaluation through robust data is important, co-design and placemaking methodologies demonstrate the adaptable processes that place-based programmes need in order to move away from traditional top-down approaches in not only recovery but research.