Across the globe, countries grapple with strains on resources and the effects of climate change on the ways populations live. Australia’s fresh water supplies are vulnerable and the nation will continue to experience water security issues. Thus, understanding the perceptions of people to the water security threat will assist in developing effective mitigation strategies. To identify these perceptions, a case study of residents in the coastal city of Townsville in north Queensland, Australia, was undertaken. A total of 299 participants were recruited who completed an online survey that, in line with construal level theory, presented water scenarios as proximal and distal in terms of spatial, temporal, hypothetical and social distances. Results were that distal threats and previous exposure to water-security threats elicited higher individual threat perceptions. This research offers considerations for future water security mitigation strategies that encourage water-saving behaviour, particularly in this region.

Introduction

Australia's fresh water supplies are vulnerable (Gleick 2012; Gregory and Hall 2011; Ray Biswas et al. 2023). This vulnerability is intensified by climate change, which has already had major implications for freshwater resources, water management and overall water quality (Beeson 2020; Gleick 2012; Pearce et al. 2013; Ray Biswas et al. 2023). Population growth and increased agricultural and industrial activities also add pressure to already strained water supplies (Gregory and Hall 2011; Sullivan 2020). As a result, there is a greater demand for water but a shrinking supply for the nation.

With climatic events having direct and indirect impacts on the way Australians live and as such events show no signs of reprieve (Bureau of Meteorology 2018; Steffen et al. 2018), there has been a substantial effort to increase water security, particularly freshwater supplies, within the country. These strategies include implementing supply limits, technological advancements in the home, access to water infrastructure, changes in water distribution structure and a significant focus on reducing demand for water (Beeson 2020; CSIRO 2011). Several methods are already in place to reduce residential water usage and water-saving campaigns are among the most common techniques to promote household water conservation (Koop et al. 2019). However, whether these methods effectively encourage desired behaviour and safeguard water supply, in addition to the other common practices (e.g. water restrictions and entitlements) is questionable. This concern is particularly critical for people who do not perceive that they have experienced water insecurity, despite Australia's frequent exposure to extreme weather events.

The conflict between an individual's exposure to and perception of an event is a problem for implementing mitigation strategies that rely on prior knowledge. To effectively engage someone in the appropriate mitigation behaviour, messages need to be relayed to an audience before the event occurs. It is also challenging to create communication that aims to change current behaviour in order to prevent future negative outcomes—people are less likely to behave under such circumstances (Lorenzoni and Pidgeon 2006). There is evidence that threat perceptions are likely facilitators of behaviour in the environmental context (e.g. Kim et al. 2013; O'Neill and Nicholson-Cole 2009; Pardon et al. 2019). Therefore, exploring people’s lived experience and 'distance' via the mechanism of threat may provide valuable information to inform behaviour-change strategies.

Research by Dolnicar and Hurlimann (2009) explored the influence that experience has on pro-environmental behaviour. For example, individual perceptions of water appear dependent on experience and water supply context in a study. Participants of that study were located in Adelaide, South Australia, and Brisbane, Queensland. Both locations had ongoing water security issues and participants were the most open to drinking recycled water (Dolnicar and Hurlimann 2009). In contrast, participants in Darwin, Northern Territory, indicated they had never been subjected to water restrictions and that they did not like the idea of drinking recycled water or that it was ‘disgusting’ to drink water from alternative sources (Dolnicar and Hurlimann 2009).

A study by Milfont et al. (2014) examined the relationship between coastline proximity and belief in climate change and support for a carbon emission policy in New Zealand. The study suggested that participants who lived closer to coastal regions may be more likely to experience weather-related events, consider future events and pay more attention to warnings about weather (Milfont et al. 2014). Results found that proximity to the coast was positively associated with an increased belief in climate change and support for the regulation of carbon emissions. Thus, such individuals would be more likely to engage in associated action, for example, preparedness or mitigation behaviour. These findings are supported by research conducted by Spence, Poortinga, Butler et al. (2011) as well as Haney (2021). These authors found that participants who had direct experience of flooding were more concerned and less uncertain about climate change and felt more confident that their actions would mitigate such a threat. Similarly, Haney (2021) found that experience with a natural hazard led to a greater belief in climate change and preparation for events and this spilled over into higher performance on household pro-environmental behaviours (e.g. recycling). Exposure to previous events or water insecurity influenced the behaviour, intentions and beliefs of participants. However, such research possibly overlooks segments of the population that are exposed to water-security threats and who may not perceive them as water-security issues.

Construal level theory

Convincing individuals to engage in preventative behaviour, particularly when that behaviour attempts to ease the effects of an environmental threat that may occur in the future, is a challenge. People tend to find environmental hazards difficult to grasp given these events can be, at times, invisible, occur gradually and are uncertain (Gifford 2011). Psychological distance is the extent to which an event, object or idea is present in an individual's direct experience (Liberman et al. 2007). For example, the predicted effects of climate change could be argued to be a psychologically distant event to an individual. The immediate effects are hard to detect, the scale is global and the eventual outcomes are uncertain. In other words, climate change is not present in an individual's direct experience. Exploring the effect of psychological distance on threat perceptions may assist in understanding how distance may influence an individual’s threat perceptions about water security.

Construal level theory (CLT) (Liberman and Trope 1998; Trope and Liberman 2003; 2010) was used to examine how psychological distance facilitates the threat perception of people. CLT proposes 4 types of psychological distance that can alter an individual's perception: temporal, spatial, social and hypothetical. CLT describes the relationship between psychological distance and the extent to which an individual's thinking is abstract or concrete. The theory's hypothesis is that the more psychological distance increases, the more abstract one's thinking (Trope and Liberman 2010). Close events encourage a person to act due to the increased ability to focus on situational cues. This is because these events have little ambiguity and uncertainty and individuals can focus on the specific consequences of their actions (Liberman and Trope 2008). In contrast, distant events may be perceived as more uncertain. Evidence suggests that this distance or events being perceived as abstract helps people make decisions that align with their core values and beliefs (Liberman and Trope 2008). Table 1 shows how each component of psychological distance is conceptualised in the current research.

Table 1: Operationalisation of construal level theory psychological distances.

| Distance | Operationalisation example |

| Temporal (time) | Future vs. Past Near future vs. Far future |

| Spatial (physical space) | Near vs. Far Here vs. Over there |

| Social (interpersonal distance) | Self vs. Other Similar vs. Dissimilar Familiar vs. Unfamiliar |

| Hypothetical (likelihood) | Real vs. Hypothetical Likely vs. Unlikely |

Limited evidence has used CLT and the concept of psychological distance in contexts with a high degree of uncertainty, for example, environmental events. In this context, particularly water security, situations may be perceived as uncontrollable and have uncertain consequences (Lorenzoni et al. 2007). Encouraging individuals to view future environmental events as concerning (i.e. having an abstract mindsight) while currently acting to reduce or mitigate such events from occurring in the future (i.e. specific goals) would be the ideal relationship between perception and behaviour in this context.

Research has attempted to explore the effects of manipulating psychological distance on the performance or intention of people to perform pro-environmental behaviours. For example, the relationship between psychological distance and behaviour was investigated by Spence, Poortinga and Pidgeon (2011) who explored and characterised the CLT psychological distances (temporal, social, spatial and hypothetical) concerning climate change. Researchers argued that many people perceive climate change as psychologically distant on all CLT dimensions and this could be the reason for declining concern and increasing uncertainty and scepticism (Spence, Poortinga and Pidgeon 2011). These researchers also aimed to determine if reducing the psychological distance of climate change risk helps promote sustainability behaviour, given the unpredictable and uncertain nature of such events. Participants completed an interview-style survey that asked about cognitive constructs relating to energy and climate change, behavioural intentions, perceptions of climate change and psychological distance dimensions. Results indicated that lower psychological distance, specifically personal and local considerations of climate change, was related to greater concern about climate change. However, in terms of action, the broader global effects of climate change (i.e. greater psychological distance) were more likely to encourage intentions to behave sustainably. The implications of climate change on distant locations may have assisted individuals within the sample considering their preparedness behaviour in response to future threats. However, it did not influence their concern regarding the effects of climate change on their own environment. These findings support that of Kortenkamp and Moore (2006) who suggested that individuals had a greater willingness to cooperate when uncertainty was low, suggesting the effect a temporal influence has on one's desire to cooperate. This finding highlights the influence delayed effects have on decision-making: the more immediate the consequences are, the more likely one will reduce resource consumption (Kortenkamp and Moore 2006).

Taken together, these findings highlight an important consideration for using CLT psychological distances in the environmental context when predicting behaviour. It suggests that close psychological distance would enable more action to occur, given the certainty of environmental events and their consequences. It should be noted that these studies were based on the large and broad issue of climate change and general environmental events. It would be useful to examine whether the findings were consistent with environmental threats of a small, localised nature, which is the focus on this study. This is supported by research from van der Linden et al. (2015) who suggested that communications should be presented as local, proximal problems with personal risks to facilitate public engagement. This is supported by Scannell and Gifford (2013) who indicated that participants were more receptive to localised messages and information compared to distant or global information.

Specific to the water security context and examining the interplay between global issues and localised events, Deng et al. (2017) investigated the mechanisms that increase an individual’s adaptive behaviour. Researchers applied CLT to the context of water security with participants who lived in a drought-prone area. Results found concrete perception of saving water (i.e. the event is perceived as proximal) plays a significant role in engaging in specific adaptive water-saving behaviours compared to an abstract perception of climate change (i.e. an event that is distal). While the study established an important connection between localised disasters and climate change, there were central points to consider for the current study. First, the sample comprised of high school students, thus limiting the generalisability of the study's findings. Additionally, the study by Deng et al. (2017) did not explicitly examine the individual components of CLT (i.e. the social, temporal, hypothetical and spatial psychological distances), thus arguably not investigating the true utility of the theory in the water-security context. While it is promising that CLT has been applied in the water-security context, these considerations are of key interest to the current study, which also applies CLT to a localised water-related event.

The psychological distance of an event could be argued to affect an individual's threat perception and, as a result, influence mitigation behaviour. In this instance, the proximity of an event or exposure to previous events are also likely behavioural facilitators. Furthermore, examining more localised events, rather than a generalised discussion of environmental events, may provide evidence for using CLT in this context. Communities that have experienced significant water security events, such as Townsville, allow for such investigations between lived experience, threat perceptions and behaviour to occur.

Case study area: Townsville

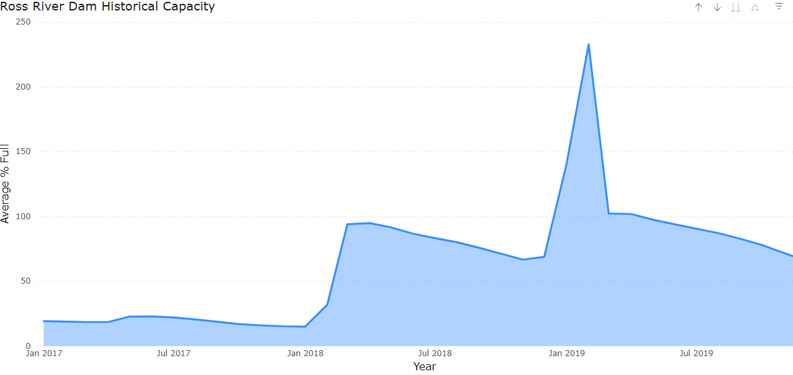

Townsville is a city on the north-east coast of Queensland, Australia and is in a climatically classified ‘dry tropics’ region with a population of 234,283 (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2021). The region's main water supply is the Ross River Dam, which was constructed in 1970 originally for flood mitigation and water storage (Townsville City Council 2020). The Townsville City Council supplies potable and non-potable water to properties within the Townsville local government area, with residents charged for their consumption based on a rate per kilolitre of usage.

Before the current study, the Townsville region had been subject to a water-security threat (drought) for almost 3 years, from November 2015 until May 2018. The area had not previously been drought declared since 2003. On 25 August 2015, the dam level fell below 40% and the Townsville community was first exposed to Level 1 water restrictions. At the height of the drought, the city experienced Level 3 water restrictions, which were enforced in August 2016. Failure to comply with these restrictions led to financial penalties for community members.