Over recent years, many regional and rural communities across Australia have experienced devastating drought, catastrophic bushfires, pandemic, mouse plague and multiple major flood events. A growing body of research has explored children and young people’s lived experience of disasters and has highlighted the centrality of local community efforts in recovery. However, recent disaster events have demonstrated an enduring need to build local community capacity to support children and young people’s recovery. Between 2021 and 2024, Community Resilience Officers (CROs) were deployed to build capacity in northern, southern and central areas of New South Wales and East Gippsland in Victoria. A developmental evaluation captured the practices associated with Community Capacity Building-Disaster Recovery (CCB-DR) and identified conditions that constrained and enabled these practices in different community contexts. This paper analyses this evaluation data through a socio-ecological lens and identifies 5 policy-relevant recommendations to improve practice. These are flexible funding for right time, right place intervention; involving children and young people in dialogue and decision-making; workforce capacity development; resourcing project leadership; and participatory research and evaluation to inform recovery capacity building interventions.

Introduction

Natural hazards disrupt the lives of children, young people, families and communities and leave trauma, grief and uncertainty in their wake (Carnie et al. 2011), and people will likely experience similar events throughout their lives (Ebbeck et al. 2020; Peek et al. 2016; Williamson et al. 2020). Disasters affect the social and emotional wellbeing of children and young people, their relationships with family and peers, interactions with school and recreation, housing and neighbourhood cohesion (Alston et al. 2019; Fothergill and Peek 2015). Yet authorities continue to overlook, dismiss and neglect the views of children and young people in decision-making (Mort and Rodríguez-Giralt 2020). This highlights the largely untapped potential of the agency of children and young people in recovery and the need to build the capacities of adults to support and engage with them (Peek and Domingue 2020).

The Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction: 2015-2030 (UNDRR 2015) states that, ‘Children and youth are agents of change and should be given the space and modalities to contribute to disaster risk reduction’ (p.23). The Advocate for Children and Young People in New South Wales (ACYP 2020) also recognises the need for children and young people’s empowerment, inclusion, choice, visibility, identity and connections and called for opportunities to share stories and to participate in recovery. Learning from children and young people can also build social, economic and environmental recognition for future generations (Sadeghloo and Mikhak 2022). MacDonald et al. (2023a) highlighted that the loss, grief and loneliness of young people continues and there remains a need to increase their empowerment in emergency and disaster preparedness.

Children and young people’s recovery depends on personal, social, situational, cultural and community factors, and their responses change over time (Gibbs et al. 2014; Mooney et al. 2017; Shepard et al. 2017). However, marginalisation and social exclusion can impair their capacities to navigate events and recover well (Peek and Domingue 2020). In this context, the capabilities of adults to support children and young people’s recovery are critical, as is the availability of support (Dyregrov 2015; Freeman 2015; Gibbs 2014; Mooney 2017; Shepard 2017). Community leaders during disasters can help to overcome the barriers of post-event isolation and overwhelmed social infrastructure (Beckham et al. 2023). Caring and supportive relationships also strengthen wellbeing by incorporating ways to cope with stress and grief (Harms 2015). Evaluation of Royal Far West’s Bushfire Recovery Program - a community-based program delivering multidisciplinary psychosocial support through 25 primary schools and 12 preschools - found positive mental health and education outcomes were reinforced by improving the trauma-knowledge and confidence of parents, carers and educators (Curtin et al. 2021).

Informal networks of individuals, groups and communities provide practical and emotional support during and after events (Moreton 2018). Their social capital is crucial to mobilise communities and increase safety, trust and recognition, which facilitate cooperation in the aftermath of disasters (Aldrich and Meyer 2015). Families, schools and communities play critical roles in recovery and preparing children and young people to successfully navigate future events (Masten 2021; Sanson and Masten 2023). The organisations that enable children’s connections with school, peers, recreation and cultural activities provide opportunities and support for building adaptive capacities (Shepard et al. 2017). These organisations may also have a role in building capacities of caregivers to cope and advocate for children and young people’s needs (Fothergill and Peek 2015; Shepard et al. 2017). After disasters, non-government organisations and businesses are uniquely positioned to quickly mobilise resources to support marginalised groups, support coordination and service delivery (Sledge and Thomas 2019).

Such evidence shows the need to explore what is required to build community capacity that supports children and young people’s recovery and preparedness. This includes the role of socio-ecological and participatory processes in resilience and sustainability.

Evaluating community capacity building practices

MacKillop Family Services1 was funded from 2021–24 to work in 4 disaster-affected regions in New South Wales and Victoria to support the recovery and preparedness of children and young people. CROs were deployed to each region and trained in the Seasons for Growth2 and Stormbirds3 programs, which are evidence-based psycho-educational wellbeing programs that help children and young people to navigate change, loss and grief.4 Evaluators from the Centre for Children and Young People at Southern Cross University were engaged to learn about the practices associated with community capacity building for disaster recovery (CCB-DR) that supports children and young people’s recovery and preparedness and the barriers and enablers of practice.

Ethics approval was obtained from Southern Cross University, number 2022/005 in February 2022.

Methods

Evaluation was informed by a socio-ecological and multi-systems perspective (Masten 2021) and aligned with the Recovery Capitals Framework (Quinn et al. 2022). Inherent in this approach is the value of participatory processes in resilience building and sustainability (Quinn et al. 2022; Sharifi et al. 2017). Developmental evaluation provides evaluative data to inform social innovation related to complex social issues and environments and contributes to action-based learning. Integral to social change projects, developmental evaluation approaches uncover and interpret processes and outcomes to inform learning and decision-making for continuous adaptation (Mitchell et al. 2021). The Theory of Practice Architectures (Kemmis et al. 2014) provided a theoretical and methodological resource to conceptualise and explore practices associated with CCB-DR. Theory of Practice Architectures also supported evaluators to ‘zoom in’ on practices where they happened and to ‘zoom out’ to identify the individual, interpersonal, organisational, environmental, cultural and systemic contexts that enable and constrain practices (Nicolini 2012).

Nine reflective practice session groups, each of 1.5 hours with between 2 and 6 participants, were facilitated by evaluators. The groups explored what their communities in each region needed, how CROs might respond and what they learnt. Additional data was collected through 7 semi-structured one-hour interviews and full-day observation of an online workshop. Feedback from children and young people was gathered by CROs during their facilitation of Seasons for Growth and Stormbirds programs and CCB-DR activities. CROs and the project lead also contributed to data analysis. Evaluators initially identified practices and then developed practice descriptions with evaluation participants to ensure accuracy and salience. Findings were synthesised with current evidence to draft recommendations that participants refined for better relevance for their communities.

CROs brought a range of experience to this work. All held relevant degree- or diploma- level qualifications in teaching, psychology or community development. All were trained as Seasons for Growth and Stormbirds program facilitators (called ‘Companions’). Table 1 shows the methods, participants and duration of CRO involvement. The authors interpreted and synthesised the findings in light of evolving literature that was informed by the Theory of Practice Architectures and socio-ecological approaches to disaster resilience.

Table 1: Methods, participants and duration of involvement.

| CRO (project region) | Duration in CRO role | Participated in interview (I), observation (O), reflective practice sessions (RP) |

| CRO 1 (NSW central) | 13 months | I + O + 4 x RP |

| CRO 2 (NSW central) | 13 months | I + 4 x RP |

| CRO 3 (NSW northern) | 12 months | I + 4 x RP |

| CRO 4 (NSW central) | 6 months | None |

| CRO 5 (NSW southern) | 9 months | 1 x RP |

| CRO 6 (NSW southern) | 10 months | I + 3 x RP |

| CRO 7 (NSW northern) | 5 months | None |

| CRO 8 (Vic East Gippsland) | 18 months | 3 x RP |

| Project Lead | Project duration | I + 9 x RP |

| Manager | Project duration | I |

| External stakeholder (NSW, central) | NA | I |

Findings

Practices associated with disaster recovery community capacity building

The evaluation uncovered 3 practices associated with CCB-DR: establishing relationships for collaboration, identifying and analysing needs and supporting adults in the lives of children and young people to understand and support recovery and wellbeing.

Establishing relationships: CROs established or developed existing relationships with school wellbeing and learning support officers, educators, principals and deputy principals; Elders and First Nations communities; mental health community workers, counsellors and psychologists; emergency services personnel, welfare service providers, local council recovery personnel and volunteers. Later, relationships were established with children and young people at the invitation of these.

Needs identification: The relationships formed the vehicle for ongoing need identification ‘on the ground’ by listening to people’s stories to learn about what had happened locally and important aspects of the community’s history and culture. CROs learnt from individuals and networks of people who shared information and strategies. CROs mapped gaps in support to identify the needs of adults and the children and young people in their lives.

Supporting the supporters: CROs tailored responses in each community to pilot and improve activities in collaboration with community representatives, the project lead and evaluators. In the early stages of the project, CROs reported ongoing hazards affecting these communities and shared the reports of adults feeling overwhelmed and unable to support children and young people, as the project lead explained:

They have the drought, fires, mouse plague, COVID. I have lost track of how many floods that have happened here since then. What we see is that professionals are willing to support children, but they're actually not able to do it at this point in time.

(Reflective practice session 2)

Responding to this, CROs initially used psycho-educational approaches to improve the knowledge and skills of adults to support children and young people’s recovery. CROs noted the absence of children and young people in many of these interactions, as a CRO described:

…there's a real gap in disaster recovery conversations that give children a voice. And last week, working with traditional recovery agencies, who are very much into the practical response… [CRO2] brought it back to the voice of the children and their experience; that is where we have a way in.

(Reflective practice session 3)

CRO Wendy Ronalds facilitated the workshop in East Gippsland, Victoria.

Image: Tim Pace

CROs were invited to directly support children and young people, for example, working alongside staff to deliver Seasons for Growth and Stormbirds or designing new programs (e.g.an ecological grief workshop for young people). Some young people reported this was the first opportunity they had to speak about the effects on them of the 2019–20 bushfires. Their feedback of the program was overwhelmingly positive (see https://vimeo.com/842783362/49d341daba).

Practice encompassed:

- raising awareness about children and young people’s participation, recovery and wellbeing

- piloting and refining psycho-educational loss, grief and recovery workshops and training

- reconnecting people to build hope at individual, family and community levels.

A workshop designed for mental health practitioners who are supporting children and young people was adapted for local hospital staff recovering from pandemic-related effects. The workshop was redesigned for disaster recovery personnel and parents/carers and then for children and young people. Rather than ‘doing for’, where conditions allowed, the CROs mobilised, co-facilitated and supported adults from the local community or school to deliver the Seasons for Growth and Stormbirds programs with multiple student cohorts simultaneously. This provided an opportunity to reach a large proportion of students while building capacity of the adults in their lives. In other settings where adults’ capacities were over-stretched, CROs delivered the programs directly with children and young people themselves.

Conditions enabling and constraining CCB-DR practices

The conditions that enabled and constrained CCB-DR practices related to the systemic, environmental and organisational arrangements like funding specifications, ongoing effects of disasters and the pandemic, organisational culture and capacity, and the evidence base informing this research. All evaluation participants identified the constraint of limited funding that prevented organisations from being able to pivot support to those places where the conditions and timing were right for the community. As CRO 3 stated:

Funding is offered for certain areas, or for certain fires, floods. But you can't anticipate what's coming up in the future. It probably needs to be a rolling CRO who can be movable into communities as and when needed, because I felt like I was perched on the side.

Timing is a constant constraint on CCB-DR practices. The COVID-19 pandemic restrictions and ongoing disaster events affected people in most of the New South Wales project, limiting community resources and requiring New South Wales-based CROs to pull back from CCB-DR practices to attend to urgent requests for support. Sensitivity to time between disaster events was important for CRO 8 who was working in small East Gippsland communities during 2023 and 2024:

These towns are really struggling. You know, it's only 4 years and that is nothing in terms of being along the journey. Four years stills feels like it could have happened a few months ago, you know. And the world’s tipped upside down since then.Interpersonally, conditions enabling CCB-DR practices were the quality of local stakeholder relationships, working face-to-face and the team’s sensitivity to the ‘right time’ for interventions.

Organisationally, there was consensus among evaluation participants that project leadership, team collaboration and group reflective practice sustained the hope and motivation of CROs to ‘stick with it’. The project lead role was not funded in the project but was internally funded in response to the complex barriers CROs faced in New South Wales. CROs appreciated the ‘willingness to let me immerse myself into the role in my way… that would probably be the most significant’ (CRO 2). Another CRO noted, ‘We've got a team leader who values people more than targets… we're really, really lucky like that’.

The quality of relationships with external stakeholders was another enabling condition. Being attuned to the exhaustion that existed within the community, CROs were still able to maintain and deepen relationships despite the ‘pure exhaustion’ and ‘overwhelm’ they witnessed. For example, CRO 6 witnessed Elders in a southern New South Wales community calling for support at a local meeting in 2022. Over months, she supported multiple responses, including co-facilitating a culturally adapted loss and grief program with the local First Nations community.

On an individual level, CRO capabilities that assisted CCB-DR included:

- adapting and being flexible

- being embedded within the community

- using trauma and healing-informed practice

- amplifying the voices of children and young people

- having knowledge and skills in CCB-DR.

Analysis of these conditions highlighted the critical systemic funding and environmental conditions that are out of the control of local community organisations. This illustrates the individual, interpersonal and organisational factors that fund support of CCB-DR practices.

Recommendations: getting the conditions right

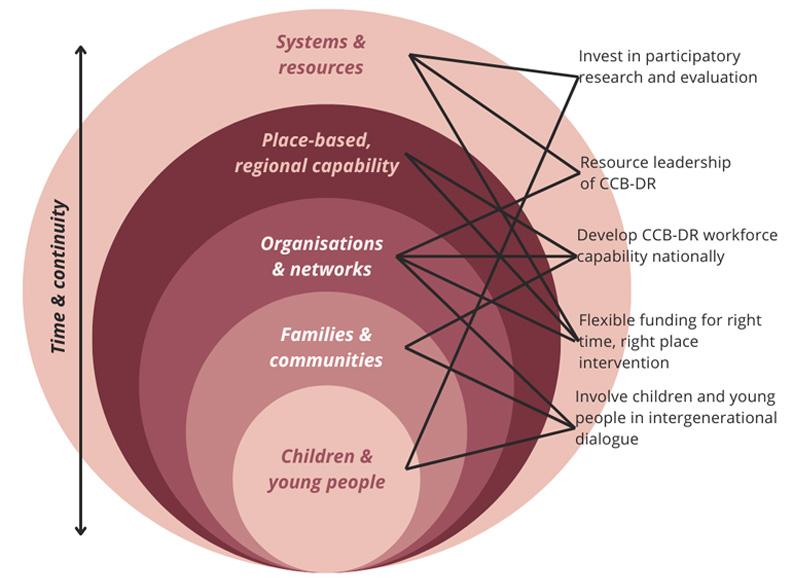

This evaluation provides insights into the practices for building community capacity to enable children and young people’s recovery and resilience. In particular, ways of relating and offering support that lay the groundwork for recovery and resilience. These findings suggest that CCB-DR practices can be improved by setting up the enabling structural, environmental, organisational, family, community and individual conditions and minimising conditions that constrain those efforts. Reflecting on these findings and the available literature, 5 recommendations are offered to set the conditions for improved CCB-DR practice (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Recommendations to improve CCB-DR practices to enable the recovery and wellbeing of children and young people.

Provide flexible funding to enable right time, right place intervention

As disaster events impact on regional communities and we learn more about what is needed for recovery for communities, families and individuals, flexible funding arrangements could enable organisations to identify and respond appropriately to need and build assets, networks and resources in communities as required. Availability of funding at the ‘right time’ and ‘right place’ would enable deployment of CCB-DR practitioners practiced in inter-generational recovery and wellbeing. Organisations need to have long-term connections in communities where socially and economically disadvantaged and marginalised populations have a high likelihood of natural hazard exposure.

Involve children and young people in inter-generational dialogue

Advocates consulting with children and young people affected by disasters urge young people’s inclusion in service design and decision-making (ACYP 2020, 2024; YACVic 2020). Their participation is positively associated with their wellbeing across social, economic and cultural life (Graham et al. 2022; Quinn et al. 2022) and models to enhance their involvement are available (Heffernan et al. 2024; Mort et al. 2018). Yet, according to Healthy North Coast (2023), disaster-affected children and young people report they ‘want a voice and a say in decisions. Many feel as though young people are being ignored’ (p.10). This suggests that still more is needed to achieve inter-generational dialogue and participatory decision-making.

Setting these conditions involves:

- recognising the rights and agency of children and young people

- supporting diverse views

- listening and participating in inter-generational dialogue

- acting on the ideas offered by children and young people.

Develop workforce capability

CCB-DR practitioners need to be knowledgeable and skilled and committed to the communities where they are deployed. They must have relevant experience, including fostering the wellbeing and participation of children and young people. We recommend a national workforce capability project to develop these capabilities in workers and volunteers. Developing CCB-DR competencies could provide a pathway for recognition of community leaders and communities-of-practice will further support communication, learning and innovation.

Resource project leadership

Working across multiple disaster-affected regions,

CCB-DR practitioners need project leaders who can motivate, support and resource them. Senior CCB-DR practitioners need capabilities in mental health and wellbeing, project management, staff support and research and policy knowledge. Investment in CCB-DR leadership provides a pathway from practice to future sustained innovation and policy contribution. We recommend resourcing of CCB-DR project leadership within, or alongside disaster grant rounds.

Invest in participatory research and evaluation

Investment is needed in participatory, developmental and inter-generational research and evaluation to understand the adaptation factors of climate-related hazards in regional and rural communities. A key finding from this project was the way CCB-DR practices strengthen the relationships and connections between adults, children and young people. This could be explored in inter-generational research and evaluation on a larger scale. While this was a small-scale qualitative project and, as such has limited generalisability, larger-scale mixed methods evaluation involving children and young people would be particularly beneficial.

Conclusion

This study analysed evaluation data through a socio-ecological lens and identifies 5 policy-relevant recommendations to improve CCB-DR practice. The study evaluated CCB-DR practices in a number of communities in regional and rural New South Wales and Victoria that were exposed to multiple natural hazards like bushfire, drought, flood and pandemic. CCB-DR can be enhanced by improvements in flexible funding for right time, right place intervention; by involving children and young people in dialogue and decision-making; by implementing specific-skills workforce development; by resourcing project leadership and by participatory research and evaluation to continually improve recovery capacity building interventions.