The circumstances faced during emergency incidents are characteristically physical, situational or time-critical, but little is known about how people manage their periods in these extreme settings. This study examined the attitudes, experiences and practices of managing menstruation by emergency services personnel in Australia while deployed operationally. Using a mixed-methods approach, a survey (n=287) collected data about operational roles, period characteristics, period management during operations and period stigmatisation. The findings show that navigating and solving the intersections between periods and the demanding circumstances of deployment is given substantial consideration by people who menstruate. Participants actively found solutions to the various routines, etiquettes and discomforts of menstruation to maintain service to their operational roles, despite problematic influences of period character and menstrual symptoms, menstrual products, hygiene, toileting, privacy and stigmatisation. Such self-determination suggests identity formation as competent first responders who also menstruate. However, externalities of menstruation that could be better accommodated in operational settings include toileting, bodily hygiene, field privacy, menstrual product supplies, used product disposal or cleaning, support, education and training. Attention to menstrual health in workplaces is increasing and should become a normalised aspect of emergency services.

Introduction

Menstruation is a regular occurrence in the lives of girls, women and people who menstruate. Part of a monthly cycle, menstruation is the shedding of the functional layer of the endometrium (the mucus membrane lining the uterus). The functional layer prepares the uterus for implantation by a blastocyst (cluster of dividing cells made by a fertilised egg) and shedding of the functional layer indicates that conception has not occurred (Norwitz et al. 2007). The endometrial (menstrual) cycle consists of 3 phases, controlled by sex steroids (hormones). The proliferative phase (from day 1 to 14 of a 28-day cycle) grows the endometrium. The secretory phase starts at ovulation and prepares the endometrium for implantation by increasing its vascular supply and stimulating mucous secretions (Dhanalakshmi et al. n.d.). Gradual withdrawal of sex steroids causes shrinking and breakdown of the endometrium, leading to the onset of the menstrual phase where the functional layer of the endometrium (consisting of blood and endometrial tissue) sheds and is expelled out of the body through the vagina. This is called menses (also known as a period) and forms day 0–5 of the next endometrial cycle (Dhanalakshmi et al. n.d.). On average, 80 ml of blood is expelled during menses, with about 50% expelled during the first 24 hours of a 3–5 day menstrual phase (Dhanalakshmi et al. n.d.). While the physiology of menstruation is largely known, the construction of social meanings of menstruation are less resolved and vary among cultures, genders and individuals.

Menstruation occurs approximately 300–400 times throughout a lifetime (Norwitz et al. 2007). On any given day, 800 million people worldwide are menstruating (WaterAid 2017). Thus, it is inevitable that the experiences of menstruation will intersect with employment. Management of menstrual hygiene in the workplace is supported by access to water and sanitation facilities, adherence to labour laws (e.g. breaks and leave provisions) and workplace practices (e.g. supervisory permissions, uniforms) (Lahiri-Dutt and Robinson 2008; Sommer et al. 2016; Fry et al. 2022). Barriers to menstrual hygiene in the workplace can arise from lack of sanitation facilities, informal and overcrowded workspaces, stigmatisation of menstruation, being unable to voice rights to water and sanitation and the affordability and availability of menstrual products (Sommer et al. 2016). One of the 5 pillars of menstrual health is the freedom to participate in all civil, cultural, economic and political spheres of life - including employment - free from menstrual-related exclusion, restriction, discrimination or coercion (Hennegan et al. 2021). Thus, it is imperative that workplaces understand, acknowledge and embed practices that support the menstrual health of employees.

Some occupations place employees in situations that generate challenging surroundings in which to manage menstruation. The characteristics of these surroundings may include thermal extremes, remoteness, danger, situational criticality and longevity, required use of protective equipment, lack of privacy, safety regulations, distance from sanitation facilities and insensitive management cultures. For example, female Antarctic fieldworkers described creative ways to manage menstrual health during remote expeditions, camping in low temperatures with required protective equipment, a lack of privacy and being in male-dominated teams (Nash 2023). Female military police described instances where situational criticality or duty regulations inhibited attendance to menstrual hygiene (Phillips and Wilson 2021). Deployed female soldiers reported issues of staying clean, soiling uniforms and interrupting team efforts to attend to menstrual hygiene (Chua 2022). Emergency room doctors reported that busy shifts (situational longevity) delayed the opportunity to take toilet breaks and that lockers with their personal belongings could be some distance away in the hospital (Rimmer 2021). Challenging surroundings are also common to the emergency and disaster management sector. Bushfire (and hazard reduction) grounds, floodscapes, cyclone paths, accident sites, building fires, search and rescue sites, command posts, incident control rooms and evacuation centres may exhibit one or more of the characteristics of challenging surroundings. However, little is known about the management of menstruation by personnel deployed operationally in emergency and disaster settings.

The aim of this study is to examine the attitudes, experiences and practices of managing menstruation by emergency service personnel in Australia while deployed operationally. It seeks to understand how aspects of menstruation are managed in challenging settings and the factors that influence the adoption of menstrual management strategies.

Methods

This exploratory study used a pragmatic, mixed-methods approach (Tashakkori and Teddlie 2008) to interpret the experiences and practices of menstruation management while deployed operationally. Close-ended quantitative and open-ended qualitative data were collected using a questionnaire (Appendix 1). Quantitative items captured the distributional occurrence of aspects of menstruation management during deployment. Qualitative items expanded on some of the quantitative items (Appendix 1) allowing participants to explain practices and experiences in detail. A parallel mixed data analysis (Teddlie and Tashakkori 2009) was applied. Quantitative data are reported as frequency distributions and qualitative responses were analysed thematically to narrate and give experiential insight to the quantitative data.

Recruitment

Study participants were recruited to undertake a survey between December 2022 and June 2023 that was presented online as a questionnaire in the Qualtrics platform. A purposive sampling strategy (Teddlie and Tashakkori 2009) was applied. Conditions for consent required that the participant was over 18, was a staff or a volunteer of an emergency services agency in a role that requires deployment operationally and a person who menstruates, or has done so in the past. People not currently menstruating (e.g. they were pregnant, breastfeeding or menopausal) were invited to contribute and answered by thinking about their experiences when they were menstruating. Participants self-selected into the study. An invitation to participate (including the link to the survey) was advertised through the newsletters, internal communications and social media of Australian emergency management agencies, networks and representative bodies. Agencies from every state and territory were approached with a request to advertise, but the researcher is unsure of the final status of every request. The study was limited to the emergency services sector; those agencies predominantly involved

in responding to natural hazard events. Personnel from ambulance, police and defence were not approached.

The study was conducted under the University of New England Human Research Ethics Committee approval HE22-193.

Questionnaire

Participants completed a questionnaire (Appendix 1) across 5 topics:

- Demographics and operational duties – contextual information on the participant and the nature of their operational role in emergency management.

- Period characteristics – data on participants’ menstrual cycles, menstrual symptoms and use of menstrual products.

- Period management while deployed operationally – data on strategies and experiences of managing menstruation while deployed operationally including planning, situational factors, managing menstrual symptoms, use of menstrual products and menstrual suppression.

- Period stigmatisation in operational settings – data on experiences of period stigmatisation while deployed operationally including assumptive comments about menstrual status, conduct of duties and impacts of stigmatisation.

- Supplementary views on menstruation and deployment – data contributed by participants when asked if there was anything they would like to add about their experiences of, or views about, menstruation and deployment that was not covered in Topics 1–4 above.

Quantitative items were answered using Likert-scales with a ‘Prefer not to say’ option. Qualitative items were optional and answered using open-ended written responses with no word limit.

The design of the questionnaire and the language of the items was constructed by the researcher to suit the Australian vernacular and to understand menstruation experiences in relation to operational roles within the Australian emergency management sector. However, the topics and items in the questionnaire were informed by various literatures. The medical literature (e.g. Dhanalakshmi et al. n.d.; Schoep et al. 2019a and 2019b) informed items about the temporal character of the menstrual cycle, the prevalence of menstrual symptoms and associations with gynaecological conditions such as endometriosis, and the impacts of menstrual symptoms on performance. Menstrual suppression (stopping periods through the use of hormonal contraceptives) is frequently adopted by US military personnel for military readiness (Phillips and Wilson 2021; Chua 2022) but the practice is debated medically (see Grant 2000; McGurgan et al. 2000; Thomas and Ellerston 2000). Several items about the use of, and attitudes towards, menstrual suppression were included in the questionnaire because of potential ‘readiness’ parallels with the emergency management sector. Socio-cultural research on menstrual experiences in workplaces (e.g. Smith 2008; Sommer et al. 2016; Barnack-Tavlaris et al. 2019; Phillips and Wilson 2021; Sang et al. 2021; Nash 2023) was used to inform items exploring the strategies used to manage menstruation and the situational factors that may influence menstrual hygiene. Critical menstruation studies is a vast literature critiquing menstruation through lenses of feminism, international development, education, human rights, labour practices, culture and psychology, among others (e.g. Bobel et al. 2020). Two areas of knowledge were considered relevant to menstruation in the emergency services operational setting: period stigmatisation and privacy (e.g. Brooks-Gunn and Ruble 1980; Roberts et al. 2002; Sang et al. 2021). Several items were crafted to understand prevalence of menstrual stigmatisation and preferences for menstruation to be revealed or concealed.

Data analysis

The study is exploratory, rather than explanatory. In the exploratory approach, the results from each topic are analysed separately and not integrated to examine causal statistical relationships between factors. Quantitative items are reported using descriptive statistics. Qualitative items were either summarised into a list of activity occurrences, or inductive thematic analysis used to identify emergent themes. The author coded text by reading for recurrent words/phrases, circumstances or experiences and iteratively condensed these into emergent themes. Each qualitative item was analysed separately.

The dataset of quantitative statistics and selected qualitative responses is available at Appendix 2.

Results

Sample description

The final sample contained 287 useable responses consisting of 261 complete responses and 26 incomplete responses. Incomplete responses were included where the participant answered one or more of the period management or stigma items. A total of 384 survey interests were registered but 97 were excluded because they were incomplete and unusable (50), did not give consent (36), were from males who did not menstruate (7) or were unreliable because of straight-lining (4). The seven male responses provided only qualitative answers about managing menstruation in operational settings. These were deemed cognate with the aim of the study but were analysed and interpreted independently.

People have a range of gender identities and menstruate (including girls, women, non-binary, boys, men, transgender). In this study, participants identified as female (97.9%) and non-binary (2.1%). No menstruating participants identified as male, intersex, trans or other (Appendix 2). Thus, the term ‘women and non-binary participants’ was used when reporting or interpreting data (APA 2020). Participant use of the binary terms women/men or female/male is retained in quotes, as are the terms used in cited literature. The gender-neutral term ‘person’ was used in the questionnaire (Appendix 1), although it was necessary in some items to use the binary women/men and female/male to imply generalised (but imperfect) distinction between women as menstruators and men as non-menstruators. The term men/male is used when referring to the 7 male-identified non-menstruators who contributed to the survey and in the discussion to imply a generalised binary of women as menstruators and men as non-menstruators.

Table 1: Organisation, role, deployment experience and menstrual status of survey participants.

| Characteristic | Items | n | % |

| Organisation | Land management agency (including forestry) | 20 | 7.0 |

| Local government | 1 | 0.3 | |

| Metropolitan fire service | 6 | 2.1 | |

| Non-government organisation | 1 | 0.3 | |

| Rescue agency | 1 | 0.3 | |

| Rural/country fire service | 221 | 77.0 | |

| State emergency service | 15 | 5.2 | |

| State government | 22 | 7.7 | |

| Prefer not to say | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Role | Staff | 70 | 24.4 |

| Volunteer | 193 | 67.2 | |

| Staff and volunteer | 24 | 8.4 | |

| Prefer not to say | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Number of deployments | Less than 5 | 47 | 16.4 |

| 5 to 10 | 53 | 18.5 | |

| Greater than 10 | 186 | 64.8 | |

| Prefer not to say | 1 | 0.3 | |

| Menstrual status | Menstruating | 194 | 67.6 |

| Suppressing menstruation using hormonal contraceptives | 28 | 9.8 | |

| Peri-menopausal (the transition to menopause) | 24 | 8.4 | |

| Menopausal or post-menopausal | 33 | 11.5 | |

| Not menstruating (pregnant or breastfeeding) | 5 | 1.7 | |

| Other* | 3 | 1.0 | |

| Prefer not to say | 0 | 0.0 |

*The ‘Other’ responses all indicated status as post-hysterectomy.

Topic 1: Demographics and operational duties

The age of participants ranged from 17 to 70 years (mean=40 years). Length of service in the emergency management sector ranged from less than 1 year to 50 years (mean=13 years). Participants were associated with a range of emergency services organisations. Most responses were from rural or country fire services (Table 1). Thus, there is bias in the results towards experiences of managing menstruation in firefighting settings. Participants were staff or volunteers (or both) and most had been deployed operationally more than 10 times (Table 1).

The operational duties and roles described by participants included firefighting (bushfire, hazard reduction, structural fire), aviation search and rescue, road accident rescue, storm and flood assistance, flood rescue, vertical rescue, remote-area firefighting, HAZMAT incident response, strike team deployment, basecamp deployment, incident management roles, control centre roles, state operations centre roles, station officers, disaster recovery, evacuation centre roles, biosecurity response, pandemic response, land-based search and rescue, surf lifesaving, catering, logistics, peer support, public information provision, community liaison and engagement, incident management, radio and communications operations, first aid, airbase management, air observation, driver, brigade leader, crew leader, senior leader, animal welfare and rescue, training officer and patrolling. Most participants reported responsibilities in more than one duty or role. The range of duties and roles undertaken by participants highlights the potential for the characteristics of challenging surroundings such as situational criticality and longevity, remoteness and environmental extremes to be generated. One participant wrote:

I am regularly deployed with as little as 2hrs notice to anywhere in the state to any kind of event that requires people. At any point I am fighting bushfires, conducting flood and storm response, rescue, conducting hazard reduction burns, in (an) incident management or control centre team or working in an evacuation centre. I spend my normal working day out in the bush with no bathroom access.

(Participant 71)

Topic 2: Period characteristics

There is not a ‘typical’ menstruator within the emergency services sector. Descriptions of participants’ periods highlight individual variability in the character of periods, preferences for menstrual products and experience of menstrual conditions and symptoms. Most participants (67.6%) were menstrual, while others were suppressing menstruation, menopausal or not menstruating because of pregnancy, breastfeeding or hysterectomy (Table 1). Regular intervals between periods were experienced by 76% of participants, while 23% of participants experienced irregular intervals between periods. Participant periods ranged from 3 to 11 days of bleeding (mean=5.5 days) with 80% of participants reporting that the number of days bleeding frequently or sometimes varied, ranging from 0 to 30 days of bleeding from period to period. As part of day-to-day life and sense of self, the majority of participants (96.5%) found their periods highly or somewhat annoying.

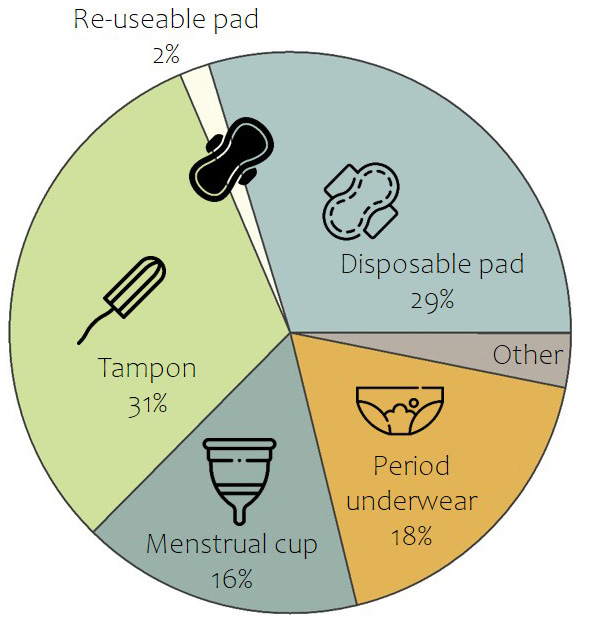

Disposable pads and tampons were the preferred menstrual products for 60% of participants, with the remaining 35% of participants preferring to use menstrual cups, period underwear or re-useable pads (Figure 1). However, participants indicated that they frequently or sometimes used more than one product during their period.

Figure 1: Preferred menstrual product use by survey participants.

Most participants (60%) reported that they had not been medically diagnosed with any menstrual or gynaecological conditions. The remaining respondents commonly experienced endometriosis, menorrhagia (heavy periods) and dysmenorrhoea (menstrual cramps). Many participants reported the co-occurrence of more than one menstrual or gynaecological condition.

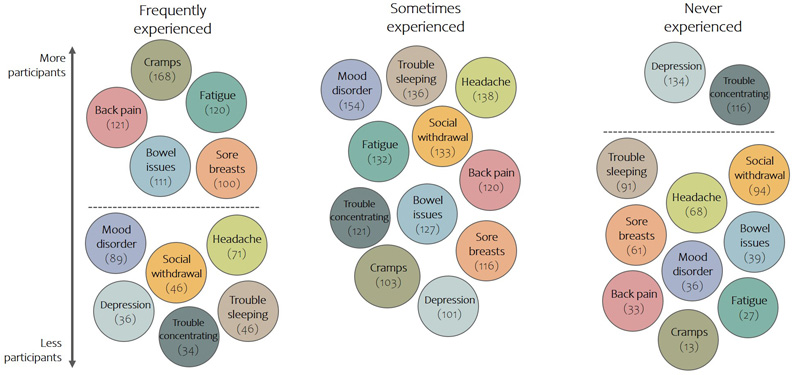

At least one menstrual symptom was experienced by almost all participants (99.7%). Cramps, back pain, fatigue, bowel issues and sore breasts were menstrual symptoms frequently experienced by many participants, whereas depression and trouble concentrating were menstrual symptoms never experienced by many participants (Figure 2). A relatively constant number of participants reported that they sometimes experienced menstrual symptoms (Figure 2). These ‘sometimes’ responses encompassed all menstrual symptoms (Figure 2), highlighting how the occurrence and type of menstrual symptoms may vary from period to period.

Figure 2: Menstrual symptoms reported as frequently experienced, sometimes experienced and never experienced by survey participants. Numbers in brackets are the number of participants reporting a certain frequency of experience of a menstrual symptom, with higher numbers towards the top of the diagram and lower numbers towards the bottom. The dashed line indicates a distinction in the numbers of participants experiencing menstrual symptoms.

Topic 3: Period management while deployed operationally

A range of experiences and strategies were evoked to manage menstruation while deployed operationally, highlighting that the management of menstruation is not passive. Attention is actively paid to the interaction of tasks, teams, performance and menstruation in relation to deployment.

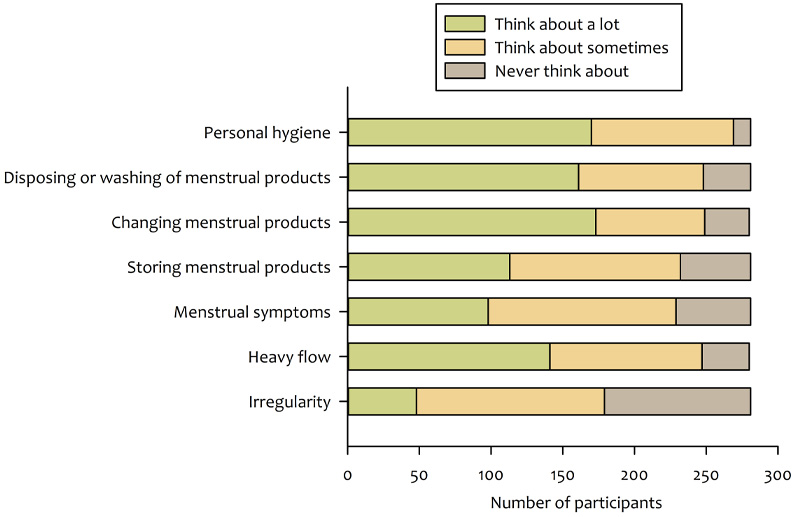

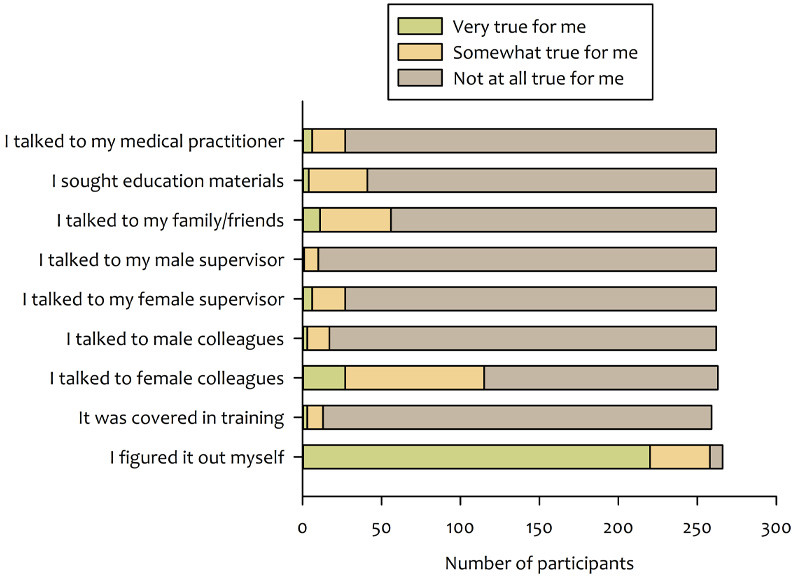

Overall, 77% of participants found it ‘somewhat difficult’ or ‘extremely difficult’ to manage their period while deployed operationally, while 23% found managing their period ‘somewhat easy’ or ‘extremely easy’. Factors arising in the deployment environment such as personal hygiene, disposing and washing of used menstrual products and the changing of menstrual products were the characteristics of periods most often thought about in planning for and during operational duties (Figure 3). For others, characteristics arising from the period such as menstrual symptoms, cramps and fatigue, heavy flow and irregularity were front-of-mind (Figure 3). Most participants learnt about managing periods during deployments by figuring it out through trial and error (Figure 4). A few others talked to female colleagues or family or friends, but learning about managing periods during deployment is rarely covered in training or discussed with male or female supervisors (Figure 4).

Figure 3: Characteristics of periods considered in planning for and during operational duties.

Figure 4: Sources of information for learning about or getting advice on managing periods while deployed operationally.

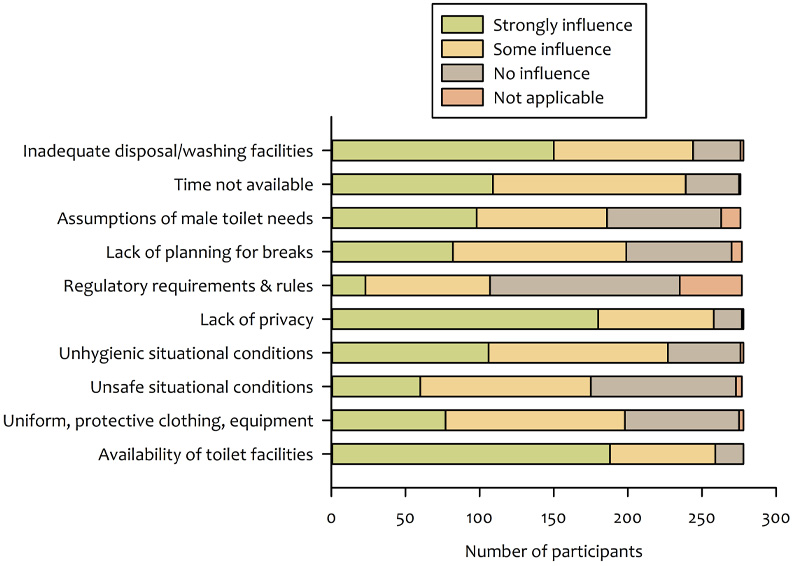

Availability of toilet facilities was considered a key situational factor influencing the management of periods while deployed operationally. Related factors included inadequate disposal or washing facilities for menstrual products, lack of privacy and unhygienic conditions (Figure 5). For others, situational factors such as time availability during busy operations, assumptions of male toileting needs, lack of planning for breaks and uniform or protective clothing influenced how well participants were able to manage their period while deployed operationally (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Situational factors influencing the management of periods while operationally deployed.

Thematic analysis of participant responses describing menstrual management during operations revealed active strategies of product choice (absorbency, avoiding leakage, ease of use, disposal and cleaning), toileting (time criticality, changing and disposing of used products, cleaning re-useable products, creating privacy within the limitations of field locations, hygiene) and preparation (planning, purchasing and carrying products, items for disposal of used products, supplies for symptom management, suppression) (Table 2). Locus of control was core to many practices, conveying a sense that participants recognised the intrinsic nature of menstrual management but paid routine attention to how to best adopt menstrual management practices suited to the circumstances of deployment. Reported practices and experiences of product choice, toileting and preparation show how attention is paid to menstrual management during deployment:

Using a menstrual cup has been the easiest as there is no need to dispose of it. If all else fails you can leave it in for long periods of time without the concern of Toxic Shock Syndrome, and it holds a good amount of blood. Additionally, if there isn't anywhere to wash it or use toilet paper to clean it up it is not the end of the world to tip out the contents and re-insert it.

(Product choice, P56)

I am a crew leader often of all males…During bush firefighter operations when things aren't as hectic I will announce to the team that I'm off to find a tree for cover to squeeze a lemon (I like making jokes about it because then the guys open up and make jokes about themselves taking a slash and shaking hands with a snake), it opens the conversation up to become easier to talk about and for safety reasons everyone then knows where or when someone has gone to the toilet. In the forest, out of sight, I will kick a hole in the dirt or sometimes dig a bit with my hands or sometimes find a large rock to hide my sanitary products under. It's difficult with timing when there is aircraft on the fireline, they're hard to hide from.

(Toileting – privacy, P209)

If I am in a building that has suitable sanitary disposal units it’s not so bad. However, it is sometimes so busy that you can’t leave to go to the toilet as often as you need to and that can lead to leakage and general discomfort.

(Toileting – time criticality, P211)

Due to the uncertainty of operations sometimes (e.g. not knowing accessibility of toilet and waste facilities or break times) means I have taken to carry a "kit" of sorts in my turn out bag with various menstrual products, zip lock bags (for disposal), wipes etc. so I always have some on hand when needed for myself and other firefighters who may need it.

(Preparation, P36)

The Standard Operating Procedures for a brigade is to be fully self-sufficient for 12 hours before relief or assistance might arrive - by default for general hygiene outside of normal toileting I make sure I have my worst case flow and pain covered for double that - no operation I have attended has made any specific effort to providing any personal feminine hygiene coverage.

(Preparation, P166)

Strategies used to manage menstruation included avoidance of deployment because of intractable issues such as situational longevity, period characteristics, lack of facilities or fear of leakage or discovery (Table 2). Unease arising from the theatre of finding toileting privacy privately, forced littering, carrying used products in pockets and backpacks, taking health risks and awareness of field safety compliance can accompany menstruation management during deployment (Table 2). Some participants described avoidant or uncomfortable experiences related to deployment:

As a volunteer firefighter I often have to plan my volunteering around my period. This leaves me at a disadvantage when trying to gain field experience and maintain parity with male field officers.

(Avoiding deployment, P68)

…For volunteer roles I will decline a request for assistance on heavy days of my period as I can’t guarantee in the middle of a land search or on a roof with the (organisation) I will need to stop, find facilities, remove overalls, disrupt operations etc. especially if I am the team leader.

(Avoiding deployment, P249)

…Keeping the tampon in – acknowledging the increased risk of TSS – is preferable to the mortifying risk of being unable to manage with only a pad and underwear and bleeding through.

(Health risk, P110)

…To change a tampon if there wasn’t enough tree cover or privacy I would ask fellow crew mates to stand watch at the work bay doors of the truck and change the tampon there, and then bury the tampon or wrap in a plastic bag until I could dispose of it on return to station or staging area. That could be very embarrassing but we were all adults and also as an older woman it wasn’t so bad. My daughter found it extremely embarrassing but does the same thing.

(Privacy, P149)

Honestly? I reckon there'd be as many used tampons on the fire ground as there are empty water bottles. There’s nowhere else to dispose of them unless you want everyone seeing them - there are options for catering and food disposal, you walk out with a tampon in your hand after hiding behind a burning tree to change it, and it's everyone's business.

(Forced littering, privacy, P131)

Further participant quotes describing strategies for managing menstruation while deployed operationally are given in Appendix 2.

Many participants (40.1%) had said no to a deployment or shift because of their menstrual cycle. Of concern, 7.2% of participants reported that they had experienced physical health issues (e.g. toxic shock syndrome, urinary tract infections) arising from menstruation management or toileting during deployments or shifts. Adjustments in the use of menstrual products to accommodate deployments or shifts was reported by 59.4% of participants. Adjustments were largely directed towards managing period characteristics in relation to the critical longevity or situational environment of deployment. The use of dual products (e.g. a menstrual cup and period underwear, or a tampon and pad), or less preferred products, during deployment assisted with mitigating the uncertainty of toileting, avoiding leakage, increasing absorbency and increasing the time between product changes. Participants described some common practices:

I use disposables when firefighting, whereas normally at home and in the ICC I use period undies, which I prefer. It is not really feasible to take your entire pants off to change on the fireground!

(Product adjustment to deployment environment, P218)

If I’m not (on a) deployment I would normally use pads but during deployments I will use period underwear as you can wear them for longer between changing them which allows me peace of mind when I don’t know when a bathroom stop will be.

(Product adjustment to critical longevity, P60)

One of the driving factors behind a shift from disposable menstruation items such as tampons and pads to reuseables such as cup and underwear was a lack of appropriate places to dispose of these when on deployment or undertaking remote mitigation activities. Lack of private and hygienic places to empty and replace the cup can still be challenging.

(Product adjustment to deployment environment, P96)

Table 2: Summary of open-ended qualitative responses describing aspects of managing menstruation during deployment. For analysis, S = summarised into a list of common activity occurrences of T = inductive thematic analysis showing emergent themes. The full questionnaire is available in Appendix 1.

| Topic and question | Words contributed | n | Analysis | Emergency themes |

| Topic 1: Demographics and operational duties | ||||

| Q1.4 Describe your operational role | 4,050 | 285 | S | n/a |

| Topic 3: Period management while deployed operationally | ||||

| Q3.4 Describe how you manage your periods during operations | 20,871 | 229 | T |

|

| Q3.7 Menstrual symptoms and effects on capacity to conduct operational duties | 5,614 | 157 | T |

|

| Q3.10 Adjustments to menstrual products to accommodate deployments | 2,917 | 135 | S | n/a |

| Q3.13 Use of menstrual suppression | 1,481 | 59 | S | n/a |

| Topic 4: Period stigmatisation in operational settings | ||||

| Q4.9 Describe comments or behaviours experienced | 2,311 | 42 | T |

|

| Topic 5: Supplementary views on menstruation and deployment | ||||

| Q4.15 Additional comments not covered in other topics | 7,058 | 113 | T |

|

The impacts of menstrual symptoms on operational duties varied among participants with 24.4% reporting no impact, 64.1% reporting some impact and 11.5% reporting a great deal of impact. For participants reporting some or a great deal of impact, thematic analysis of the impacts of menstrual symptoms on operational duties revealed attitudinal behaviours that support active continuation, perseverance and commitment through menstrual discomfort (Table 2). Menstrual symptoms are actively managed with the use of over-the-counter medications (e.g. paracetamol, ibuprofen) and attention to hydration, nutrition, fatigue, mood and self-care (Table 2). Routines are also commonly altered to adjust to menstrual symptoms (and their interaction with period management), including declining deployment, avoiding certain tasks or changing the type and location of duties (Table 2). Practices of active continuation, symptom management and task adjustment were reported by participants:

Menstrual symptoms don’t impact the way I carry out duties, they just make it harder for me physically and mentally to do the job…That is to say, the outcome of conducting operational duties is the same but it takes much more physical and mental effort.

(Active continuation, P33)

So far my menstrual symptoms haven't influenced my operational duties significantly, at least not that I am aware of. There may have been some decrease in concentration and increased tiredness, which could have influenced my performance especially in the control centre. This does not affect my performance on the fireground though. The tasks and circumstances on the fireground make me forget that I am on my period. I take paracetamol for headaches.

(Active continuation, symptom management, P191)

I find that I fatigue more easily while having my period. I also need to go to the toilet more often, which is inconvenient when in the field. I also find that at the end of a shift when I am sore and tired, I'm more sore and tired when I've had to worry about managing my period all day, and my lower back pain / cramps can be compounded by the hard physical activity of firefighting.

(Active continuation, P34)

Headaches, cramps and back pain were sometimes an issue, but manageable with pain killers. Periods never affected my response to deployments.

(Active continuation, P69)

Pain and fatigue are the main culprits – I carry painkillers (Panadol/ibuprofen) in my bag and keep food/snacks to eat to help with fatigue.

(Symptom management, P36)

I get a lot more tired and so if I can choose to do so I will do shorter days. If I can’t choose, I will just battle on through until I can get home and fall asleep.

(Active continuation, task adjustment, P29)

I have paracetamol on hand and will use super pads to allow for a long time between changes. I have also taken a role as assistant to the strike team leader in a forward command vehicle rather than actively fight fires on a truck as it is more comfortable.

(Symptom management, task adjustment, P47)

…I carry generic over the counter painkillers which is effective at managing my pain levels and doesn't impact my cognitive function. If I'm angry, snappy or agitated I feel mostly comfortable enough sharing with my colleagues that I've got a case of PMS or asking to be put on a specific task that will keep me from potentially clashing with anyone inappropriately. I haven't had a scenario at an incident where I haven't been able to operate effectively due to pain or discomfort.

(Symptom management, P166)

Further participant quotes describing the effects of and responses to menstrual symptoms while deployed operationally are given in Appendix 2.

The use of menstrual suppression (stopping periods through the use of hormonal contraceptives) specifically to accommodate deployments or shifts was reported by 26.1% of participants. Operational readiness was often mentioned as a driver of the use of menstrual suppression, but participants who had used menstrual suppression held a range of views about their comfort with this practice as part of menstrual and reproductive health:

I am ex-military and would do this often for deployments and field exercises.

(Operational readiness, P37)

It contributed to my decision to take the pill. Over summer I don't have periods to be safe if I am deployed.

(Operational readiness, P49)

I used to take the contraceptive pill to reduce the heaviness of my period to be more available for deployments and to improve acne. I no longer take the pill due to not wanting to be on this long term. I do not feel that menstrual suppression is healthy.

(Operational readiness, reproductive health concerns, P65)

Topic 4: Period stigmatisation in operational settings

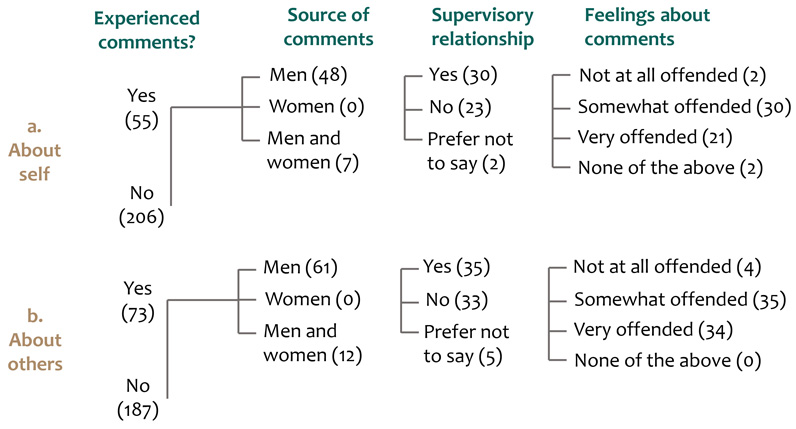

Incidences of period stigmatisation by colleagues were present but relatively infrequent in the study sample. Most participants had not experienced targeted, unwanted or assumptive comments from colleagues about their own menstrual status and the conduct of their duties nor had they observed comments made about others (Figure 6). However, period stigmatisation was experienced or observed by about 25% of survey participants. Targeted, unwanted or assumptive comments about a participant’s menstrual status and conduct of duties most commonly (but not always) came from men, sometimes (but not always) from supervisors, and generally caused offence (Figure 6a). Overhearing targeted, unwanted or assumptive comments about the menstrual status of others and conduct of duties also commonly (but not always) came from men, sometimes (but not always) from supervisors, and generally caused offence (Figure 6b).

Thematic analysis of the reported experiences of period stigmatisation commonly described inaccurate attribution of behaviours, moods or requests to menstrual status (Table 2). Also revealed were accompanying strategies used to counteract stigmatisation, and acknowledgment of the importance of support from male colleagues (Table 2). Participants noted:

Just the odd derogatory comment about women being ‘on their period’ and being moody etc. which I shut down very quickly.

(Inaccurate attribution, counteractive strategy, P95)

It is extremely annoying as a female officer to have a correction to someone’s behaviour or work mumbled about as “must be her time of the month”. As I have got older and more experienced I will not tolerate it any longer and will take the person to task. Depending on their vulnerability I will take them aside and discuss it or I will simply call them out then and there. It has been an extremely rare thing to happen in my experience and always felt that the majority of members were extremely aware of the problems it caused for women on the fireground.

(Inaccurate attribution, counteractive strategy, P149)

As I went through menopause I had a particular experience of coming home from a fire on a very hot day after the cool change had come through, sitting 4 across the back in a Cat 1 with me in the middle and getting a hot flush. The crew were absolutely wonderful and immediately wound down all the windows helped me out of my jacket and just carried on with their usual banter of the homeward journey. Those things really matter.

(Support from male colleagues, P149)

Further participant quotes describing experiences of period stigmatisation while deployed operationally are given in Appendix 2.

In an operational setting, many people (42.6%) had disclosed their menstrual status to others, while others (56.6%) had not. Of those who disclosed their menstrual status, most (60.7%) felt ‘very’ or ‘somewhat’ comfortable with the response to that disclosure, while some (34.0%) felt ‘very’ or ‘somewhat’ uncomfortable with the response. The majority of participants (59.3%) preferred to keep their menstrual status completely private in the workplace, while others preferred to keep their menstrual status somewhat private (36.5%) or not at all private (3.8%). Most participants (66.8%) felt that the topic of menstruation should be discussed openly by everyone, men and women, while others (8.7%) felt that the topic of menstruation should only be discussed among women or not openly. Many (23.7%) did not agree that the statements about openness described their feelings. Thus, even though incidences of period stigmatisation are relatively infrequent in this sample, many participants were negotiating the co-existence of personal privacy preferences alongside beliefs that the topic of menstruation should be normalised.

Topic 5: Supplementary views on menstruation and deployment

Four themes were identified from analysis of participant supplementary views about managing menstruation while deployed operationally. First, toileting and hygiene in operational settings, particularly in the field, was front-of-mind and echoed the theme extracted in Topic 3. Access to toilets for urination, defecation and menstruation management, privacy for field toileting, maintaining hygiene (e.g. clean hands), disposal of used menstrual products and planning for toilet breaks were commonly stated views (Table 2). Worker rights, equity or health and safety framings suggested a perceived inattention to toileting as part of operational settings. Participants noted:

I feel it doesn’t affect the job. What does need to be addressed is proper facilities. Males just urinate in the bush. Or they get porta toilets for bowel movements but there is nowhere to discretely or even at all dispose of menstruation products when away from stations on jobs or on deployment…You want to do the task without highlighting the fact…I don’t think we need to make our male colleges talk about it with us. We just need to be able to discretely manage menstruation and a lot of time in logistics that isn’t even a thought.

(Toileting inattention, equity, P62)

I believe that having access to bathroom facilities and access to toilet breaks on deployment or while on a callout is a right that all male and female volunteers should have. This is a major issue that needs to be addressed. My brigade shed doesn't even have a bathroom, which is fine for the men or so they tell me, but as the only active female in the brigade, it is quite frustrating that I can't access a bathroom while on a callout, training, brigade meeting or doing brigade maintenance.

(Toileting inattention, equity, P205)

…I think about people who come from backgrounds of sexual assault or from more conservative religious backgrounds than myself and think that offering better toileting facilities will help them be more comfortable.

(Toileting inattention, equity, P29)

I feel like managing menstruation in operational settings is pretty similar to managing pooing in operational settings; no one talks about it but everyone just gets on with it. Everyone poos, and everyone either menstruates or knows someone who does…

(Toilet access, bodily functions, P221)

Second, the idea that menstrual hygiene products should be, or were already, part of standard ‘kit’ on appliances, in base camps and, in operations centres was commonly mentioned (Table 2). Participants noted how supplies could counteract characteristics of periods such as irregularity or heavy flow, or the uncertain circumstances of operational environments, thereby maintaining operational readiness. A menstrual kit is also a visible mechanism to normalise menstruation and relates to the broader theme of normalisation extracted below. Participants noted:

We now have (organisation) issued feminine hygiene packs on the trucks. It’s a great step to inclusion. And a subtle way of making the men aware it’s an issue. We need to make it normal to talk about.

(Normalisation, P49)

Some time ago we put tampons on our fire trucks at the brigade I volunteer with, these were well received until we got a new captain who disagreed with it so they were removed. It’s only in the last 12 months that the brigade executive agreed to put them back on the trucks and are now a standard item on the weekly check lists.

(Normalisation, P120)

Vehicles (trucks) need to have menstrual products at all times as women can be caught short or underprepared, especially at menopause or puberty.

(Counteracting period characteristics, P69)

At my brigade there had been no consideration for the female or menstruating members. Since I joined, I have fought for certain things on all appliances to ensure our ability to turn out at any time of the month.

(Operational readiness, P248)

Third, responder identity and competency being independent of menstruation status was commonly expressed by participants (Table 2). Self-identity as first responders who are competent, effective and get on with the job while also managing menstruation across a spectrum of ease to difficulty, were described with various narratives. These narratives may have been offered at the end of the questionnaire to counteract the bounded items that asked about menstruation management practices and period stigmatisation experiences. Dichotomies about wanting to normalise menstruation versing attention on menstruation being used to embed existing gender stereotypes or to limit opportunities in male-dominated operational cultures were also raised. Participants noted:

Women are more than capable of getting the job done, whether they are menstruating or not.

(Responder identity, P168)

I don’t actually think it’s an issue at all. The more basic need to have access to bathroom facilities is probably far more important. I’ve never needed accommodations to be made because I may or may not have a period, and I’ve never been on a crew with any other female who has either.

(Responder identity, P160)

I take the approach that it's not going to hold me back, but I do have to prepare for it…I know that if I am in a prolonged situation with respite not certain, that I may, at worst case scenario bleed through my uniform. If that were to happen, well too bad for those who may be offended. My focus is on preservation of life not someone’s sensibilities. There have been scenarios where I have been in a vertical rescue harness for over three hours, there is no option to urinate, change tampons etc. It is what it is and due to being hyper-focused on the task at hand I don't find it an issue.

(Responder identity, P234)

…It can be seen as creating another stereotype to manage, but the reality is that people are going to be uncomfortable before it gets better and we have to recognise that we have to stand up to the base level gender discrimination and push beyond. That will make people uncomfortable, but also it might just make men more aware of the silent struggles we women were fighting on the frontline.

(Embedding stereotypes, P196)

In the past I was always quiet about menstruation as I didn't want to create another reason that may be seen as why women shouldn't be on fire ground. Now that I am older and in a brigade with confident outspoken women I embrace being open and discussing managing menstruation in an operational setting.

(Embedding stereotypes, P124)

Let’s not give people more ammunition for exclusionary behaviours please.

(Embedding stereotypes, P85)

Fourth, understanding and normalising menstruation in operational settings was seen as an important endeavour (Table 2). Including menstruation in training and operational practice, talking openly about the topic, learning from experience, connecting with colleagues for support and reducing menstrual stigma and inequality were mentioned by participants as different pathways to understanding. Participants noted:

I think opening up a dialogue about menstruation would be a good thing, seeing as many females are now taking on roles within emergency services. It shouldn’t be something to be ashamed about and having information, education and help will benefit all members.

(Dialogue, P104)

I don’t feel it’s up to the ‘organisation’ to manage menstruation in operational settings but rather to work on de-stigmatisation and general supports for women in operations……

(Dialogue, P146)

I think managing your period while being deployed should be covered as part of basic training. This should be attended by both men and women…. I would be happy to talk about it. Share my experiences, if it helps.

(Training, P191)

As a training instructor, I have started discussing this topic with learners at (courses). I talk about it from an operational preparedness perspective: asking women to consider how their menstrual cycles may impact their ability to perform their duties, and how they might prepare for/manage this, and asking men to bear this in mind when a female colleague asks for toileting concessions over and above what they might consider "normal".

(Training, P213)

I think that the issue does not need to be forced as a topic to be discussed. The women in our brigade talk openly. I don’t discuss it with the male members. But I know if I needed to they would respect and assist in any way if I requested.

(Support from colleagues, P178)

The men in my brigade have been supportive and have never made this an issue. They have wives and children and so this is part of their lives.

(Support from colleagues, P184)

Further participant quotes describing supplementary views of menstrual management while deployed operationally are given in Appendix 2.

The unexpected responses received from non-menstruating men suggest an interest in, and support for, understanding menstruation during deployment. Comments aligned closely with the themes of toilet facilities, situational environments and support as identified by participants who menstruate:

As a male crew leader, I ensure that the women in the crew look after each other in regards to managing menstruation. And if any issues arise then I am available any time to listen privately.

(Support from colleagues, Male 6)

…in my time I have seen almost all females under my command manage themselves with few issues. However, there are issues, the main ones being working in remote areas…, lack of understanding for females when toilets in the field are implemented…, control centres being geared for smaller numbers of staff that is way exceeded in large long-duration incidents…, lack of laundry facilities…

(Toileting, hygiene, privacy, Male 7)

Figure 6: Experiences of targeted, unwanted or assumptive comments from colleagues about a) one’s own menstrual status and b) another person’s menstrual status. The first branch shows the number of participants with this experience, the second branch who the comments came from, the third branch identifies a supervisory relationship and the fourth branch reports how the participant felt upon hearing those comments.

Discussion

The circumstances faced during operations are characteristically physical, situational or time-critical. The findings of this study show that navigating and solving the interplay between periods and the demanding circumstances of deployment is given substantial consideration by the women and non-binary participants in this study. They actively find solutions to the various routines, etiquettes and discomforts of menstruation to maintain service to their operational roles, responsibilities and duties. They find these solutions despite the frequently challenging influences of period character and menstrual symptoms, menstrual products, toileting, privacy and stigmatisation. Such attention to managing menstruation in the demanding circumstances of deployment suggests an identity formation that merges the professional with the menstrual-bodied self, which I label as ‘first responders who also menstruate’. The active problem-solving and service to professional roles identified in this study is similar to that reported in the few studies that have examined menstruation management in other extreme environments, for example the military (Phillips and Wilson 2021), Antarctic expeditions (Nash 2023) and hospitals (Rimmer 2021). This study is the first (to the author’s knowledge) exploring menstruation in the Australian emergency management sector and has observed the practices and experiences of personnel deployed operationally during natural hazard events.

Freedom to participate in all spheres of life, including employment, is a pillar of menstrual health (Hennegan et al. 2021). However, that freedom is often invisibly bounded. Sang et al. (2021) suggested that those who menstruate have additional and distinctive physical and emotional labour to carry out, which they termed ‘blood work’. Aspects of blood work include managing the messy, painful, leaky body; planning access to facilities; avoiding feelings of shame and being stigmatised; and, managing workload in relation to menstruation (Sang et al. 2021). In this study, blood work occurs in the context of the way that women and non-binary participants found solutions to maintain service to their operational roles, responsibilities and duties. In the already demanding circumstances of deployment, participants devoted additional physical and emotional labour to pain management, avoiding leakage, finding facilities, concealing and disposing of used products, suppressing periods with hormones, planning ahead, buying and storing a range of products, bodily hygiene, pushing through discomfort, adaptive unease, forgoing deployment opportunities, concealing menstrual status, adjusting mood, explaining themselves to others, maintaining privacy, caring for self, caring for others, correcting behaviours, reducing stigmatisation for self and others and lobbying for practice change.

That this additional labour is contributed by staff and volunteers in service to operational roles and responder identities is a remarkable testament to the capabilities and commitments of women, non-binary and other gender identified people within the Australian emergency services sector who menstruate. Such labour is unlikely to be recognised through the standard markers of remuneration, allowances, performance appraisal or promotion.

Despite the prevalence of active strategies to manage menstruation while deployed operationally, access to toilet facilities and/or field toileting privacy was consistently identified as an important factor influencing success. Timely changing of menstrual products; the disposal, storage or washing of used menstrual products and attending to menstruation-related bodily hygiene were closely connected to toileting, although participants often noted that toileting supported the bodily functions and wellbeing of all people (e.g. for urination and defecation as well as for menstrual hygiene). The intersections between toileting, privacy and menstruation management resemble those reported in other extreme settings. For Antarctic expeditioners, managing bodily fluids requires practice and pre-planning in shared spaces and within strict temperature-safety and waste-management policies (Nash 2023). For military women, the lack of toilets and showers negatively affected attitudes towards menstruation (Trego and Jordan 2010). A report on toileting in field-based electrical trades showed that women’s amenities were frequently treated as an inconvenience, improperly and/or irregularly serviced or not provided at all (ETU 2021). As suggested by Nash (2023), toilets might be sites used to maintain hegemonic masculine norms and control access to male occupational domains. The diverse range of roles and tasks described by study participants occur within a spectrum of toilet forms, from a built incident control centre or command centre to a temporary staging area to a remote field site. Understanding and supporting the best practices and logistics of toileting in these different operational settings would benefit all deployed personnel.

The World Health Organization calls for menstruation to be recognised, framed and addressed as a health and human rights issue; not as a hygiene issue (World Health Organization 2022). Menstrual health is the state of complete mental, physical and social wellbeing that includes access to information, supportive facilities and services, treatment and care for menstrual-cycle related discomforts and disorders, a positive and respectful environment, choice of participation and freedom from menstrual-related exclusion or stigmatisation (Hennegan et al. 2021). Accommodating menstrual health is increasing as a focus of workplace law and policy. British Standard 30416:2023 seeks to ‘assist organisations to understand which actions relating to menstrual and peri/menopausal health can be taken to protect the welfare of employees in the workplace, and to make the work environment more suitable for everyone’ (BSI 2023, p.2). In Australia, the Senate Community Affairs References Committee is undertaking an inquiry into issues related to menopause and perimenopause. The terms of reference include (but are not limited to) workforce participation and productivity; the level of awareness among employers and workers of the symptoms of menopause and perimenopause and the awareness, availability and usage of workplace supports (Parliament of Australia 2024). An independent review of workplace culture and change at the Australian Antarctic Division, commissioned following the study of Nash (2023), made recommendations to improve workplace safety, including a holistic approach to people, safety and inclusion on-base in Antarctica (Russell Performance Co. 2023). Studies in US military settings suggest that the promotion of women’s health in all aspects, including menstruation, supports professional soldier identities and maintains operational readiness within a traditionally gendered occupation (Phillips and Wilson 2021; Chua 2022). However, acceptance of menstrual health in Australian workplace settings is not entirely resolved in debate, law or practice. For example, Nash (2023) questioned whether, in building inclusive field environments, menstruating Antarctic expeditioners should have to adapt to cisgender male-dominated field environments or whether organisations must adapt to the presence of menstruators. Goldblatt and Steele (2019) remind readers how anti-discrimination laws have been evoked to fight ‘protective’ functions preventing reproductive women from accessing certain occupations and that clear prohibitions against discrimination on the basis of menstruation do not yet exist. The findings in this study about toileting, active menstrual management strategies, responder identities, deployment avoidance and period stigmatisation indicate that much experiential knowledge is held within emergency service agencies and that health policies and guidelines cognisant of managing menstruation in the extreme circumstances of deployment could be built from that knowledge.

This study revealed that most participants learnt how to manage their periods during deployment by ‘figuring it out themselves’, sometimes from colleagues but rarely through induction or training. Qualitative responses signalled a desire for improved understanding and normalisation of menstruation as an aspect of operational practice. However, desire to know more and to de-stigmatise and normalise discussion of menstruation while deployed operationally was also sitting alongside a range of individual preferences for maintaining menstrual privacy in operational settings. The socio-cultural origins of menstrual stigma and taboos are complex but have many documented negative consequences for women’s health, sexuality, wellbeing and social status (Johnston-Robledo and Chrisler 2013). People who menstruate may have internalised hostile-sexist, pathological-behavioural or pollution beliefs, become hyper-vigilant about revealing menstrual status or self-police and monitor presentation through the lens of a critical male gaze (Johnston-Robledo and Chrisler 2013; Nash 2023). Incorporating menstrual education into practice reforms or organisational training would require a sensitive and stigma- or trauma-informed approach that does not inadvertently override the prevailing independence and self-determination reported here as active strategies to manage menstruation in the challenging circumstances of deployment. Listening, documenting and experiential co-learning for flexibility and inclusion may be a path as suggested by the findings of this study.

Social meanings of menstruation by men are often constructed as negative (menstruation as disgusting, to be hidden or controlled) or hostile-sexist (the menstruating woman as irrational, demanding or dangerous) (Peranovic and Bentley 2017). Peranovic and Bentley (2017) found another social construction whereby the views of men (positive and negative) about menstruation were formed through important relationships with girls and women in their lives. All social constructions were revealed in this study. The unexpected interest of men in the survey, and the support from men frequently reported in operational settings by women and non-binary study participants, suggests that many men are seeking to understand menstruation and assist those with whom they have important team or supervisory relationships. Conversely, reported incidences of period stigmatisation may reflect pervasive negative or hostile-sexist views of women and non-binary personnel who menstruate. However, this study was not designed to include men who do not menstruate and there is a need for further research about their perspectives of menstruation during deployment.

Study limitations and future research

There was substantial bias in the sample towards experiences of managing menstruation in firefighting settings (Appendix 2). Initial and follow-up recruitment requests were sent to emergency service agencies in each state and territory but it is not possible to ascertain if requests were ultimately approved and actioned for posting in internal staff bulletins. Recruitment was enhanced in a rural fire agency with a defined research adoption strategy and resourcing. One participant noted:

This is the first time I've seen the service openly use the word menstruation, in their newsletter where they advertised this survey. I was shocked but happy to see it. We have so many amazing people who menstruate in the service and we need to talk about this more often…

(P204)

An exploratory research approach was adopted to examine practices and experience of menstruation during the challenging circumstances of deployment because there was little background literature or previous examination of this topic within the Australian emergency services sector. An explanatory approach, with a different aim and study design, might be applied in further work to test statistical relationships between dependent and independent menstruation variables and demographic co-variates, for example.

It was not the intent of the study to deliver organisational or operational recommendations, only to understand the practices and experiences of menstruation in the extremes of deployment. The voices of participants suggest that responder identities and the labour of problem-solving and independence by people who menstruate must be respected, while also recognising that externalities such as toileting, operational routines, education and training are potential areas of organisational improvement. Future research might ask personnel about how to translate the findings of this study into operational practice, training, logistics and management. Future research might also consider field toileting as a topic of significance; the opportunity costs of choices to avoid deployment or specific tasks; explore how, where and why menstruation stigma and taboo occurs in the emergency management sector and the influence of specific conditions such as endometriosis on managing menstruation while deployed operationally. Given the reported significance of toileting for managing menstruation, equivalent research might explore men’s experiences of managing bodily functions in the extreme circumstances of deployment. The interest of men in this study suggests that it would also be useful to collect views of male-identified personnel about aspects of menstruation management during deployment.

Conclusion

The inevitable intersection between menstruation and occupation is particularly prominent for people deployed operationally in the emergency services where environmental, time or situational criticality may disrupt regular routines of menstrual management. The findings show that people who menstruate navigate the criticalities of deployment and actively find ways to adjust and adapt menstrual management to maintain service and commitment to their operational roles, responsibilities and duties. For some people adjusting and adapting is reasonably easy, but for most there are difficulties of period character, menstrual symptoms, menstrual product limitations, privacy, operational practices and taboos or stigmas to overcome. Attention to menstrual health in workplace settings is increasing and is likely to eventually require organisational leadership and policy responses with greater complexity arising in male-dominated and extreme environments. Both are characteristics of the emergency services sector. Support for women’s menstrual and reproductive health as a normalised part of responder identity is a worthy aspiration, advantaging greater workforce participation, equality and diversity. One participant summed this up:

I believe that women are excellent at managing themselves and their periods for the most part. Some things are beyond their control and difficult to manage, but we do what we can in the situation. I do also believe things could be made a little easier for women to manage this part of themselves that occurs naturally and yet tends to be a taboo subject. I feel incredibly uncomfortable disclosing my menstrual status to anybody in the workplace or operational setting. But it should not be that way, it should be discussed as openly as any other health matter.

(P112)