Leadership in times of volatility and uncertainty has come under increasing scrutiny. There is a need to critically examine how crisis management leaders develop their leadership practices and what leadership practices are needed to support teams, stakeholders and communities in conditions of transition, change and deep uncertainty. Just over a decade ago, Owen (2013) reported research that examined the gendered nature of incident management. That research included a survey of emergency response agencies that were members of the Australasian Fire and Emergency Service Authorities Council (AFAC). Survey respondents included 476 men and 77 women. In incident management teams the women surveyed were predominately in planning and logistics functional team leader positions and, of the 117 incident controllers/deputy controllers included in the study, only 4 (5%) were women. The research reported that women experienced working in such teams as culturally challenging, in part because of a masculinist culture often referred to as a ‘command and control type attitude’ (Owen 2013, p 7). In considering this, this paper explores the representation of women in leadership positions in emergency management and what attributes women bring to these roles. The paper concludes by proposing a move beyond gendered stereotypes of leadership (masculine/feminine) towards the metaphor of ‘leader as host’.

Background

Traditional ways of leading crisis response, often referred to as ‘command and control’, have been criticised as unresponsive and insufficiently agile in dynamic conditions (O’Rourke and Leonard 2018). The recent reviews of responses to extreme weather emergencies in New Zealand1 identified overconfidence of response leaders and a lack of leadership in building collaborative multi-agency, community-focused capabilities and operating procedures were significant inhibitors to effective response. While ways of organising are changing, the cultural norms of crisis management leaders are also changing. This challenges the traditional conception of leadership towards a more communal (i.e. people-oriented) definition. In this context, new conceptualisations of leadership are emerging that requires effective ways of enhancing stakeholder knowledge as well as innovative skills and abilities to work in teams rather than to focus on pure tasks and outcomes.

Leader as hero – archetypes of command and control

Traditionally, emergency services organisations have been structured hierarchically with clear command-and-control arrangements. Command and control is defined as ‘the exercise of authority and direction by a properly designated commander over assigned and attached forces in the accomplishment of the mission’ (O'Rourke and Leonard 2018, p.3). The framework has its origins in the military and the historical legacy is still present in, for example, the ranking structure (e.g. captains, commanders) used in many organisations.

Stereotypically, masculine qualities such as ambition, independence, dominance and rationality are associated with the traditional, hierarchical component of leadership that is characterised by instrumental behaviours (i.e. being goal-oriented) and represented by the so-called ‘think leader - think male’ stereotype (Schein 1973). In discussing the cultural changes needed in the police force in the United Kingdom, McKergow and Miller (2016) note that while heroic leadership is important in, for example intense situations, this style of leadership risks disempowering those who are being commanded, in part because it privileges the leader ‘over’ the team. They comment that:

...this style of leadership is defined as the strength of the leader’s will and deference of their team, who act almost like an extension of the leader: executing duties without asking questions.

(p.3)

These historic approaches to crisis leadership are in contrast to a more open communicative type – the leader as host (Wheatley and Frieze 2011; McCrystal et al. 2015).

Leader as host – archetypes for engagement

To address the challenges of leading in uncertain conditions in ways that are adaptable, there has been a call for more collaborative and relational forms of working to build multi-stakeholder commitment and engagement in solving ‘wicked’ problems (Dentoni 2018). Leaders need to draw the best out of their teams without treating them as foot soldiers (McKergow and Miller 2016) because only with group input will we be able to generate the solutions needed for novel, complex and wicked problems.

Instead of hierarchical or directive leadership styles, relational leadership is the interactive influence among individuals in groups for which the objective is to lead one another (Pearce and Sims 2002 in Gartzia and Van Engen 2012). Looking for leaders who are adept at consensus-building and engagement requires interpersonally oriented leadership. This includes helping and showing concern for subordinates, looking out for their welfare and being friendly and available, which does not coincide with the traditional masculinist leadership role (Long et al. 2019).

Host leadership acknowledges that in times of uncertainty and volatility leaders are not totally in control of what happens (McChrystal et al. 2015). What they can do is set a context and creates background conditions for teams and other stakeholders to do what needs to be done (Owen et al. 2015). The metaphor of host yields valuable practical connections for leadership development (McKergow 2015).

Building leadership capability

This paper reports on findings from a review of data collected during the last 5 years of a leadership professional development programme conducted in New Zealand for response and recovery leaders. Response and Recovery Aotearoa New Zealand (RRANZ) is a programme to develop leaders operating in disasters.2 It provides professional training for response and recovery leaders working in the public and private sectors across the country’s all-hazards National Security System at local, regional and national levels. To enter the programme, participants must be working in an emergency response or recovery role. To complete the programme, participants undertake a 7-week online course and complete an intensive week-long face-to-face course. During this period, participants engage in a series of exercises and discussions with a range of experts working in the sector. As part of their preparation for the course, participants undertake a 360-degree feedback process where they provide their perceptions against a Leadership Capability Framework (RRANZ 2019)3 and invite others (peers, managers, direct reports) to provide feedback on their performance against those capabilities.

We have used data collected as part of that feedback process to address the following questions:

- Where are we now in terms of representation in emergency management leadership positions?

- What have we learned about men and women in these leadership roles?

- What comes next?

Representation

To explore whether there are gender4 differences in the ways in which men and women self-report their leadership capability and the degree to which others perceive leadership capability, an analysis was conducted of a database containing 157 responses from alumni who have completed the programme (Table 1).

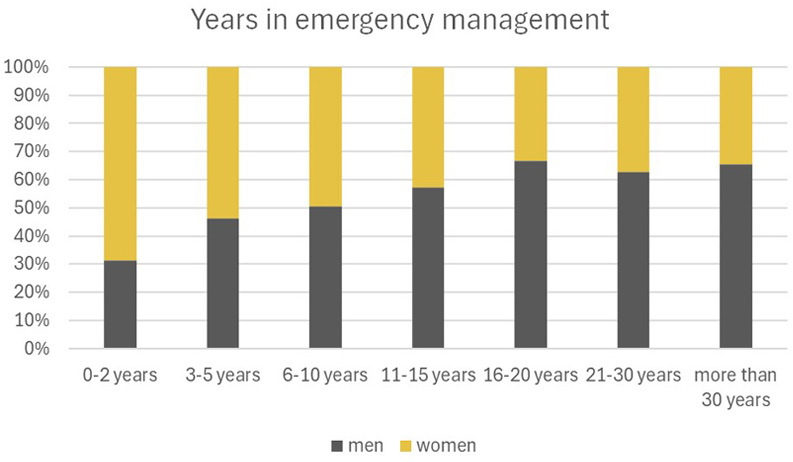

The survey asked participants to report how long they had worked in emergency management. Table 2 shows that women are relative newcomers to working in emergency management, having a median experience of between 3 and 5 years, compared to the men who had between 6 and 10 years. Figure 1 illustrates the proportion of men and women within these experience bands.

Table 1: Responses from the 360 feedback on leadership capability.

| Responses | Self-reports | Other reports |

| Male | 97 (62%) | 645 (61%) |

| Female | 60 (38%) | 418 (39%) |

| Total | 157 (100%) | 1063 (100%) |

Emergency management leadership capability

The response and recovery capabilities used to assess performance are organised into 6 themes.

1. Setting direction: Thinks, analyses and sets direction with long-term objectives in mind, making sound decisions based on complex information where there is uncertainty, ambiguity and significant consequences. Includes:

- strategic thinking - sets and adjusts strategic direction in a dynamic environment to determine wider goals

- information and opportunities - takes an intelligence-driven approach to sense-making, situation development analysis and decision-making to create and maximise opportunity through collaborative use of information

- problem-solving and judgement - makes effective decisions in appropriate timeframes with the right tools

- agility and innovation - generates and adapts to new approaches, is flexible to shift focus and actions, works with pace.

2. Leading people: Builds, leads and extends leaders and teams to bring out the best in people and create a strong and positive culture, shared direction and high performance. Includes:

- achievement through others - delegates and maintains oversight of work responsibilities and leverages the capability of recovery/response management teams, governance, peers and partner organisations to deliver outcomes

- empowerment - enables others to act on initiative to develop and improve their performance

- building culture - shapes, influences and models a culture that empowers others to deliver

- diversity - ensures the workforce reflects and develops diversity of people and perspectives

- lifting team and individual performance - builds cohesive and high-performing teams and brings out the best in direct reports and their people to deliver collective results that are more than the sum of individual efforts

- developing talent - coaches and develops diverse talent to build the people capability required to deliver outcomes.

Table 2: Years working in emergency management.

| How many years of experience (overall) have you had in emergency management? | ||

| Years of experience | Women (Cum%) | Men (Cum%) |

| 0-2 years | 15 | 11 |

| 3-5 years | 19 | 26 |

| 6-10 years | 11 | 18 |

| 11-15 years | 8 | 17 |

| 16-20 years | 4 | 13 |

| 21-30 years | 3 | 8 |

| more than 30 years | 2 | 6 |

| Total | 62 | 99 |

3. Managing relationships: Inspires confidence and builds strong trust relationships, engages with teams, communities, iwi, stakeholders, advocates, political representatives and partners to identify needs, influence actions, negotiate solutions and jointly deliver on response/recovery goals and plans. Includes:

- connecting with people - builds trust and be a leader that people want to work with and for

- engaging with communities - appreciates, partners and supports communities and represents response/recovery effectively and positively in community contexts

- multi-agency collaboration - works collaboratively with lead, partner and support organisations

- leading at the political interface - engages and represents within and between the public sector, iwi, private sector and community leaders to shape, negotiate and implement national, regional, local and community priorities

- communicating with influence - communicates in a clear, persuasive, impactful and inspirational way, listens to others and responds with respect, convinces others to embrace change and take action

- social and cultural intelligence - applies understanding of individual and group behaviour, culture and community dynamics to relationships

- developing networks - establishes and maintains connections that benefit performance.

Figure 1: Proportional representation of men and women by experience in the emergency management sector.

4. Managing self: Self-aware and actively manages own skills, qualities, attitudes and emotional state. Maintains effectiveness, momentum and stability of self and others when facing stress and challenges. Knows own capabilities, strengths and gaps and learns from every situation. Includes:

- self-awareness - leverages self-awareness to improve skills and adapt approach quickly

- curiosity and open-mindedness - shows curiosity, flexibility and openness in analysing and integrating ideas, information and differing perspectives

- honesty and courage - delivers hard messages and makes unpopular decisions to advance the best interests of people and communities

- emotional control - manages own emotional state under pressure and sets the tone for others, helps others maintain optimism and focus

- resilience - shows composure, grit and a sense of perspective when the going gets tough

- ethics and integrity - holds themselves accountable for their actions, respects democratic, professional, ethical and people-values, builds respectful, diverse and inclusive workplaces.

5. Engaging and partnering with Māori: Builds the knowledge, capability and mana to engage with Māori in an effective and valued way. Understands role and responsibilities in relation to the Treaty of Waitangi and actively partners with whānau, hapū and iwi in response and recovery. Includes:

- partnerships under the Treaty of Waitangi - as a leader, understands and promotes the importance and relevance of the Treaty of Waitangi for response and recovery and fulfils partnership obligations under the Treaty

- understanding Te Āo Māori - develops and uses understanding of te reo Māori and tikanga Māori in range of informal and formal settings

- engagement with Māori - engages and builds successful enduring relationships with Māori at iwi, hapū or whānau levels (relevant to the situation) that influences decisions and actions.

6. Delivering results: Translates strategy and decisions into action and plans and prioritises effectively to make sure the right things happen. Focuses on getting things done with and through others to coordinate activities and create change and benefit in communities. Includes:

- achieving ambitious outcomes - demonstrates achievement drive, ambition, optimism and delivery focus to make things happen and achieve results

- organisation and system performance - works collectively across system boundaries and levels of response/recovery, communities, stakeholders, elected officials, government agencies, business and partners to deliver sustainable improvements to systems and communities

- leading change through people - chooses and applies the right change management approaches to the context to support successful change

- programme management - translates strategy into action through managing across projects and change activities to deliver community benefits

- managing work priorities - plans, prioritises and organises work to deliver on short-, medium- and long-term objectives

- resource management - secures and makes the best possible use of resources, capabilities and assets to deliver on objectives.

The following are the questions and options for self and other assessment:

- NA/No opportunity to demonstrate - no or very limited experience in the situations in which you were expected to be able to demonstrate the capability.

- Has opportunity but did not demonstrate - you've had the opportunity but not felt that you could demonstrate the capability.

- Developing - you've demonstrated the capability in some straightforward situations with guidance and advice.

- Competent - you've demonstrated the capability quickly and competently in moderately complex situations, with limited guidance.

- Highly competent - you've demonstrated the capability in major situations in a fluid, flexible, highly proficient manner without guidance.

- Advanced - you've demonstrated the capability in the most severe and complex situations at the highest level.

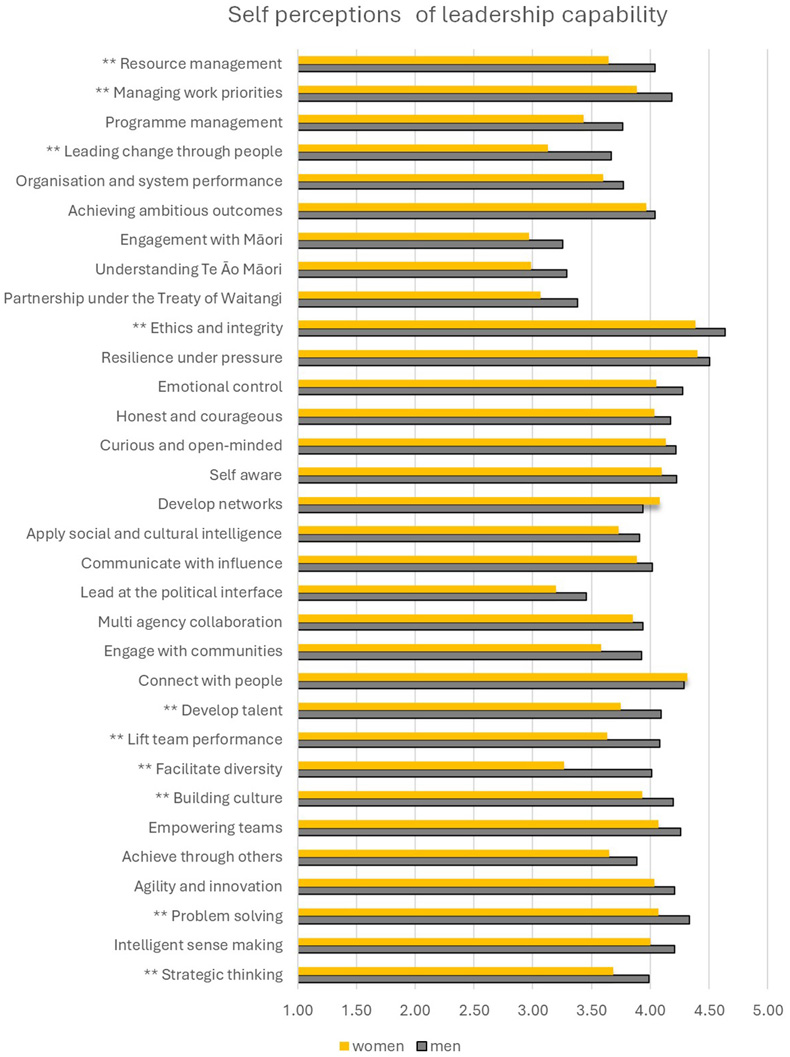

Figure 2 shows that male participants rated themselves more highly than women on all but 2 of the capabilities. The 2 capabilities female participants rated themselves highly on were ‘Connect with people’ (to build trust and to be a leader people want to work with) and ‘Develop networks’ (to establish and maintain connections which benefit performance). Higher self-reports from men may be because they have worked in the emergency management sector for longer. It may also suggest that men regard themselves as capable because they are comfortable and confident with their leadership identity, especially within a traditional culture of command-and-control. This is a common theme in the literature (see Aggestam and True 2021; Garikipati and Kambhampati 2021; Waylen 2021).

Figure 2: Self-assessment on leadership capabilities: women (yellow) and men (grey). Note: Items asterisked ** are statistically significant at the p<.05 level

These findings illustrate that the gender imbalance in emergency management noted a decade ago is gradually changing. However, women underestimate their skills in key emergency management capability areas relative to males and this may influence their willingness to take on, or put themselves forward, for leadership positions.

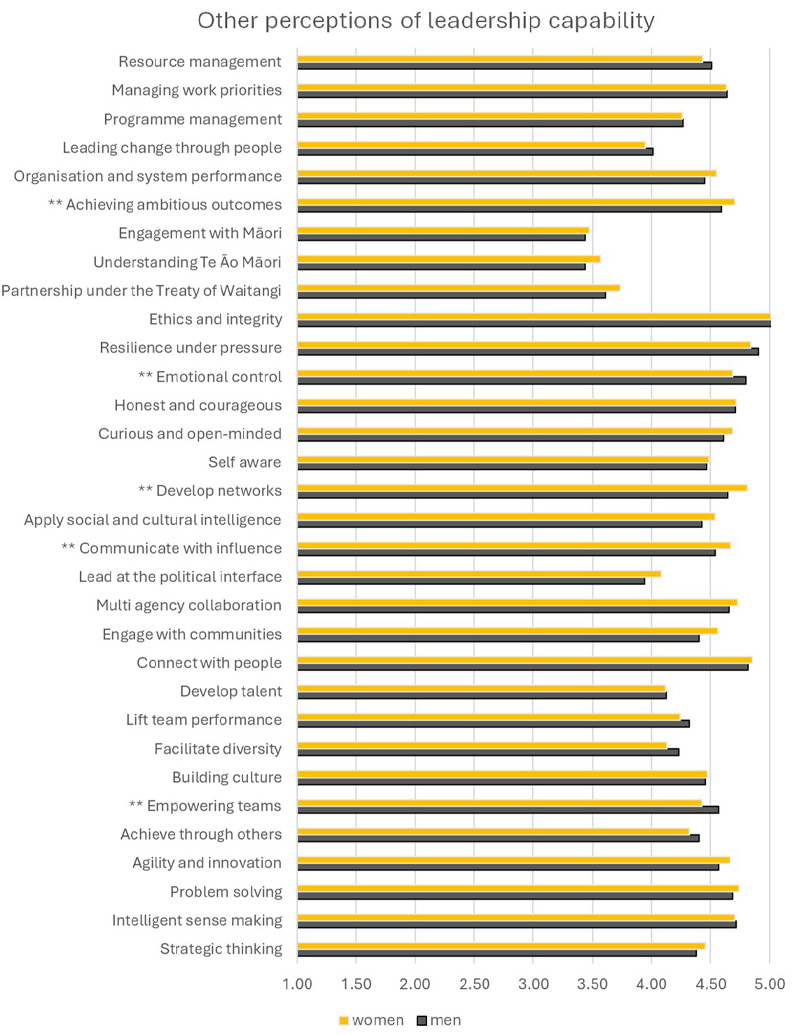

Of interest is that, in contrast, feedback from others on the assessment of leadership capability rated women higher on more than half of the capabilities than their male counterparts. Figure 3 shows that women were rated highly on the capabilities of achieve ambitious outcomes, develop networks and communicate with influence at statistically significant levels. Applying social and cultural intelligence, leading at the political interface, multi-agency collaboration, engagement with communities, agility and innovation, problem-solving and strategic thinking were all reported at higher levels of performance than for men. Feedback received from others indicated men rated higher on leadership capabilities of resource management, empowering teams and emotional control.

Figure 3: Others assessment on leadership capabilities: women (yellow) and men (grey). Note: Items asterisked ** are statistically significant at the p<.05 level.

Discussion

There has been ongoing discourse within the literature about feminine and masculine styles of leadership with claims that female attributes are needed in the future (Blake-Beard, Shapiro and Ingols 2020; Gerzema and D'Antonio 2013; Gartzia and Van Engen 2015; Hardacker 2023). We eschew this approach and instead look to the leader as host as an appropriate metaphor. These data show that while the host leader behaviours show up in this study strongly in women, this is because, arguably, they have been enculturated into adopting behaviours associated with consensual interpersonal interactions. Similarly, masculine leadership styles (e.g. of obtaining resources) are indicated in these data as showing up more in men.

Men and women leaders need to build on the strengths they have developed over time and develop the attributes of hosting. Host leaders integrate the attributes indicated by both genders in this study. Host leaders set the context; they protect their teams by taking on supportive and engaging roles and they enable others to achieve results. Host leaders are not servant leaders because, while they serve, they are also responsible for others in their accountabilities. Host leaders participate in the events they lead and they balance the need to step up and to plan, arrange and direct with the need to step back, nudge where necessary and bring out the best in others (McKergow and Miller 2016). McKergow and Miller (2016) also noted a host leader is clearly an authority figure but one whose authority comes from personal engagement, from attention to detail, connection and invitation. A good host leader knows when to intervene and be proactive and when to step back.

Where to next

These data suggest that women are clearly capable but underrate the qualities they bring to their leadership roles. The data also suggest that male domination within the sector is shifting. While response and recovery roles are including more women, it is important to continue to encourage women into these leadership positions. This requires attention to create work cultures that are supportive to different styles and approaches. In addition, it is important to address any barriers that exist so that workplaces are welcoming (e.g. considering family obligations for men and women).

We suggest it is time to review the Leadership Capability Framework (RRANZ 2019). For example, capabilities such as ‘emotional control’ are no longer fit for interpersonal interactions that require emotional intelligence. Leaders who perceive themselves as expressive (i.e. including traits such as being empathic, sensitive or concerned with other’s needs) are reported in the literature as more effective leaders (Gartzia and Van Engen 2012).

These findings provide opportunities to consider the ways in which differences in leadership identity are both part of the problem (heroic) and part of the solution (host). The findings challenge researchers and practitioners to move beyond gendered identities to ones fit-for-purpose in volatile and uncertain worlds.