Fire and Emergency New Zealand (Fire and Emergency) is committed to developing a diverse and inclusive work force. While wāhine (women) have played an active role serving in urban and rural fire services since the 1940s, they remain significantly under-represented throughout Fire and Emergency, especially in leadership positions. Responding to an identified gap in knowledge about career experiences and expectations of the organisation’s wāhine firefighters, Fire and Emergency commissioned a mixed-methods study. The primary source of data for the study was a series of interviews with 29 wāhine firefighters.1 This was supplemented with relevant administrative data to provide background and context to the interview material. The overall aim of this research project was to foster understanding of wāhine firefighters’ experiences in relation to barriers and enablers of their career development and progression, and thereby provide an important input to the changes required to make positive progress.

Setting the scene

Relevant Fire and Emergency administrative data were analysed to produce a profile of wāhine firefighters within the organisation at the current time, and to show how that profile has changed over time. Key points from inspection of the administrative data (as of 30 June 2022):

- Low representation of wāhine – operational firefighters make-up the majority (72%) of Fire and Emergency’s wider workforce, and yet it is this role within the organisation where the lowest levels of female representation are found:

- wāhine are a minority within career (5.7%) and volunteer (15.0%) firefighting workforces (or 13.5%, when both groups are combined)

- wāhine firefighters are especially under-represented in leadership roles. Wāhine hold just 3.4% of executive officer leadership roles, 2.3% of paid operational leadership roles (Senior Station Officer/Station Officer) and 5.4% of volunteer firefighter leadership roles (Crew Leader or more senior). - Variable but generally slow progress – the representation of wāhine firefighters has increased over time but, compared to other male-dominated industries, overall progress (particularly for career firefighters) has been slow. Gains in representation reflect a steady increase in the proportion of wāhine firefighters within annual cohorts of new recruits, which is occurring at a higher rate than among annual departures. However, progress is uneven, with an uptick in wāhine career firefighters exiting in 2021–22.

- Shorter length of service for wāhine – the average length of service of wāhine firefighters is considerably below that of tāne (men). It takes time for wāhine to progress their career and the tendency for wāhine to have shorter periods of service is limiting the numbers available to move into leadership roles. This is particularly evident for career firefighters where the average length of service for tāne is 17.1 years, but for wāhine just 7.7 years.

- Gender equity indicators poor across countries – comparison of Fire and Emergency service data across other countries suggests Aotearoa New Zealand sits somewhere in the mid-range when compared on gender representation in firefighter roles, as well as other gender equity indicators. It seems that all countries could benefit from work to improve the representation and standing of wāhine firefighters.

Currently, there is no readily available and continuously updated set of indicators by which progress can be monitored (e.g. a dashboard of indicators or regularly produced report), pointing to an area for improvement. Ensuring that data relevant to progression and development of wāhine firefighters are available, published and regularly monitored could play an important role in promoting and sustaining change.

The study showed that low representation of wāhine persists within the operational firefighters of Fire and Emergency’s workforce.

Image: Fire and Emergency New Zealand

Interviews with wāhine firefighters – a complex landscape with variable responses

On completing the interviews with the 29 wāhine, perhaps the most notable finding was the wide variability in the nature of their responses. Significantly, most had high-levels of satisfaction within their respective roles, but their experiences of factors that either hindered or helped them to develop and progress varied greatly. A particular issue (such as brigade leadership) might be experienced by some wāhine as a barrier, while for others it was an enabler. Further, different themes had very different levels of significance across those interviewed.

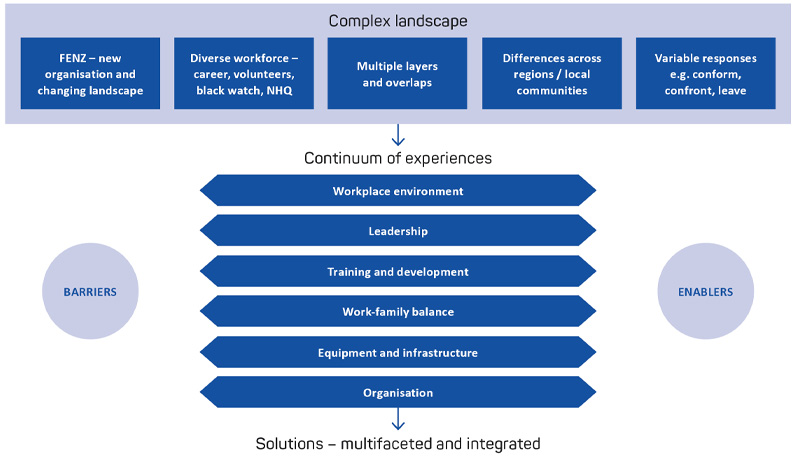

In making sense of the qualitative data, it became evident that a very complex ‘landscape’ underpinned the dataset. An attempt to represent this complex landscape, including the various dimensions along which such variability in responses was observed, is given Figure 1.

Five background domains emerged as central to the complex landscape upon which this study was conducted (see 5 tiles in Figure 1). These included:

- the new and evolving nature of the organisation, with much change occurring since the establishment of Fire and Emergency in 2017

- the diverse nature of the workforce and the differing working conditions for those in ‘career land’ versus ‘volunteer land’

- the complex and overlapping nature of issues involved

regional differences creating a ‘postcode lottery’ of experiences across and within regions - the variability among wāhine not only in what they experienced but in how they typically responded to challenges.

This range of responses was particularly evident in comments from wāhine firefighters in response to gender-based differential treatment. The diversity of responses can be summed up by example (actual) comments made: ‘I don’t see it’, ‘it doesn’t offend me’, ‘I deal with it head on’, through to ‘it exhausts me!’.

The interaction of features and resulting variability in wāhine views and experiences meant the barriers and enablers identified in this study were best considered as continuums of experiences, organised into 6 themes (double-ended arrows in Figure 1). In general, there was more variability than consistency in wāhine views and experiences.

Figure 1: The complex landscape that shapes the experiences of wāhine firefighters.

Barriers and enablers to career development and progression

Six themes emerged in understanding the key barriers and enablers to the development and career progression of wāhine firefighters. The primary focus was on factors affecting career progression, although some themes extended into retention of wāhine firefighters as an integral consideration.2

Workplace environment – the strongest theme to emerge among the wāhine related to experience of their workplace environment, and in particular the effect of culture of that workplace.

I was talking to a friend the other day and I said like... I don't think I'll be accepted as a brigade member. I'm tolerated as a brigade member but, like, I don't know that I'll ever be accepted.

(Volunteer firefighter)

Comments identifying barriers tended to outnumber references to enablers.

- Barriers – wāhine experienced non-inclusive environments that were disempowering and unsupportive of their career progression as well as the existence of subcultures or ‘tribes’ associated with different groups within the workforce served to reduce opportunities for progression and development.

- Enablers – these consisted of a mixture of factors that helped them endure the more hostile aspects of their work environment but also those that were more direct enablers of their career progression. Examples included brigades with an overall inclusive nature and informal mentoring and support from colleagues.

Responses to the study showed that wāhine firefighters easily identified gender-based differential treatment in the workplace.

Images: Fire and Emergency New Zealand

Leadership – the role of leadership emerged as a strong theme among wāhine both as a barrier and enabler to career progression depending on the particular skills and attributes of their leaders. This theme had considerable overlap with workplace environment, with the brigade leader playing a significant role in how the culture of the brigade developed. Brigade leaders could, however, also have more specific impacts on career progression in their roles as mentors and as gatekeepers of training and development opportunities.

- Barriers – leaders could act as a barrier to the retention of wāhine and to their career progression. Experiences ranged from blatant discriminatory behaviour by the leaders of the brigade through to inaction and ineffectiveness that resulted in negative outcomes.

- Enablers – encouragingly, it was more common for wāhine to describe leadership in terms of enablement. This occurred through direct actions such as proactive career guidance (e.g. shoulder tapping), coaching before interviews or training courses and enhanced confidence resulting from affirmation and encouragement.

Training and development opportunities – training and development inevitably were important themes in this study. Within this were experiences of training, particularly courses held at the National Training Centre and access to developmental opportunities.

- Barriers – negative experiences of training and/or the absence of formal career planning were 2 significant barriers to the career progression and development of wāhine firefighters. The former was more specific to wāhine, but the lack of career planning and other opportunities appears to apply equally to wāhine and tāne firefighters.

- Enablers – there were several ways training and development opportunities were experienced as enabling. These included openings and opportunity to develop different skills and people networks within the organisation, positive training experiences enhanced by the presence of female trainers and attendance of other inspirational female-themed professional development opportunities (e.g. conferences).

Work-family balance – despite a majority of the wāhine interviewed being ‘working mothers’ at some stage of their careers (approximately 70%), few brought this topic up without prompting. There was a degree of acceptance of the challenges posed of juggling work and family responsibilities, with the sentiment that ‘you just make it work’ commonly voiced. On probing, it became apparent that childcare was a pervasive issue in relation to career progression for wāhine. Managing childcare responsibilities presented stressful challenges to wāhine firefighters and restricted access to developmental opportunities.

In terms of identifying specific barriers and enablers, most of the discussions centred around the factors that created special difficulties (barriers) as well as strategies that helped wāhine manage these challenges (enablers).

- Barriers – special challenges to managing childcare responsibilities included childcare being expensive and ill-suited to shift workers, the pressures to do overtime and the ‘massive mum guilt that kicks in’, the burden on families created by residential training courses and the need to travel, challenges of coming back after pregnancy and childbirth. A few wāhine spoke of the effects of being a firefighter on relationships. Those who raised this, described tensions created by them working in (at times) hostile workplaces.

- Enablers – factors that eased barriers included access to support, mechanisms to keep family members informed on childcare needs, the availability of different career paths to suit personal circumstances and - for volunteers - the implementation of local and innovative solutions. The presence of these factors meant wāhine were less likely to be in the position where they had to choose family over career. While these were described as enablers for wāhine, many apply to tāne with caregiving responsibilities.3

Equipment and infrastructure – this theme provoked frequent and animated responses with poor-fitting uniforms and protective gear the most common topic of conversation. Many were exasperated with a lack of improvements despite the issue being around for decades. This theme was distinct in that wāhine spoke only of difficulties experienced with no enabling factors identified.

- Barriers – issues with ill-fitting uniforms, protective gear and inadequate fire station facilities created barriers to the retention of wāhine firefighters as they had negative effects on job satisfaction. They created health and safety concerns, impeded the ability of wāhine to work efficiently and made them feel like they didn’t belong.

‘Nothing is a bigger daily reminder that you don’t belong here than the uniforms’.

(Career firefighter)

Organisational experiences – in general, wāhine did not say a great deal about Fire and Emergency as an organisation. There was a clear disconnect between their own ‘truck world’ and the work of those in national headquarters responsible for the operations of the organisation. This disconnect was evident in low levels of awareness of (or interest in) organisational priorities and values.4 When prompted to share thoughts on their experiences of organisational processes, there was recognition of the role of the organisation in achieving change for wāhine.

‘Organisation’ as a frame potentially subsumes all of the issues dealt with under the theme headings above. Those highlighted were additional organisation-related aspects identified by the wāhine and not accounted for within other ‘themes’.

- Barriers – organisational processes were experienced as inefficient, especially human resources, the complaints resolution process and implementation of roll outs. The appointment processes, in particular, were considered as unnecessarily lengthy, insufficiently transparent and lacked feedback when knock backs occurred. The combined effect was one of de-motivation to participate any further in the process.

- Enablers – wāhine recognised the role of the organisation in achieving progress when working conditions were compared to those of 20, 10 or even 5 years ago. Wāhine also spoke optimistically that Fire and Emergency appeared genuinely committed to improving things and to developing a diverse and inclusive workforce, which was an important consideration for those wāhine planning a long career within the agency.

The study included many responses about poor-fitting uniforms and protective gear that had not improved for decades.

Image: Fire and Emergency New Zealand

Supporting career development and progression

Wāhine identified a range of support activities that they felt would facilitate the career development and progression of wāhine firefighters. Comments included types of support wanted, but also views on how best to implement or deliver the support.

Types of support activities

The types of support activities wāhine identified largely revolved around what was needed to address the barriers or to enhance enablers they had previously identified. Support activities more directly related to career development and progression. These appear first in the list below, while the ones important to wāhine but relating more to retention appear lower down (the ordering below is not intended as to convey prioritisation):

- structured career planning advice – for example, annual performance reviews and professional development planning sessions with ongoing support to achieve career goals identified

- programmes to develop future leaders – establish a systematic approach to identifying and supporting future leaders (including wāhine),including formal mentoring and sponsor-type systems

- accessing developmental opportunities – ensure equitable access to relevant developmental opportunities (e.g. secondments, deployment opportunities, project work, taking on local representative roles)

- making learning more attractive – for example, more females in trainer roles, flexible styles of instruction to suit wāhine, increased use of distance learning where possible and scheduling courses so wāhine have the option of attending with other wāhine

- supportive and inclusive workplace environments – continue this important and complex area of work to enable wāhine to take up opportunities and develop the skills and confidence needed to progress into leadership roles while also maximising their retention

- developing effective and inclusive leaders – provide early and ongoing opportunities to develop leadership skills, supporting wāhine to develop and progress into roles they value as well as continue/expand the concept of male champions to advocate and model inclusive behaviour

- access to wāhine networks and mentors – for support, guidance, inspiration and as a lever for collective action to provide support for wāhine to contribute to the work of Women in Fire and Emergency New Zealand (WFENZ), increase awareness of achievements and understand and address misperceptions associated with participation in the network

- flexible working and support with childcare – continue to explore options for job/shift sharing to enable flexible working, provision for childcare that is suitable/affordable for those on shift work; adopt family friendly conditions for those attending training courses and support brigade innovations that offer solutions (e.g. volunteer brigade creche and nannies)

- eliminating unconscious bias and structural barriers – removal of unconscious gender bias in language (e.g. more consistent use of firefighter/firefighters than fireman/firemen) and structural barriers in recruitment and appointment processes (e.g. inclusion of wāhine in interview panels, increased transparency around appointments)

- effective resolution of complaints – recognise the valuable role that WFENZ and the Women’s Development team at Fire and Emergency provide as ‘safe places’ to access confidential advice and support; ensure wāhine feel supported, are made aware of the range of options available to them and can retain control over decisions impacting them

- providing ergonomically suitable clothing and gear – this is essential for wāhine to carry out their work safely and effectively and to feel like they belong, ensure wāhine are included in the decision-making around equipment procurement and increase awareness and access to current options to remedy poorly fitting gear (e.g. tailoring, special orders).

The study showed that wāhine were optimistic that Fire and Emergency were committed to developing their roles operationally.

Images: Fire and Emergency New Zealand

Overall approach to delivery – inclusion and respect

One of the consistent messages from wāhine in this study was that they did not want special treatment nor to be singled out in any way because they were wāhine. Instead, they wanted to be seen and valued for their work as firefighters.

‘…it doesn’t feel good being overlooked, but it doesn’t feel good catching the updraft’.

(Career firefighter)

This meant they were generally unsupportive of diversity-led goals achieved through gender-based quotas or targets. Wāhine were, however, supportive of inclusive and equitable practices where they were not disadvantaged because of their gender.

The views of the wāhine in this study align with those found by other researchers, which point to the achievement of effective diversity being a long-term proposition that requires commitment to the creation first of an inclusive culture. Achieving an inclusive and respectful workplace will enable wāhine who are progressing their careers to be able to ‘step up to a place of safety’.

The following 3 aspects of an overarching approach were endorsed by wāhine in this study:

- initiatives that achieve targeted goals for wāhine but delivered as organisation-wide projects – most, if not all, of the support activities identified by wāhine could benefit both wāhine and tāne firefighters and should be delivered as an organisation-wide project without prioritising a gender

- expert advice from wāhine needs to be integrated throughout the organisation – the scale of the work required for wāhine to have equitable access to opportunities to progress their careers needs to be recognised and requires integrated working across the organisation, with expert advice from wāhine embedded across all processes and work programmes

- leverage the strong team-based culture and value placed on high performance – a focus on how team performance can be enhanced through becoming more diverse, adding a wider range of skills and attributes, will be less polarising than simply arguing for more diversity within the workforce simply because it is the ‘right thing to do’.

Conclusion

In understanding the barriers and enablers to the career development and progression of wāhine firefighters, this study found the experiences of wāhine and their responses to these experiences are highly variable (particularly across volunteer brigades). This means wāhine may not need (or want) the same level or types of support and blanket approaches to delivering change may not be effective.

It was also confirmed that there is no ‘silver bullet’ that might rapidly guarantee organisation-wide improvement in the representation of wāhine firefighters in leadership positions. Instead, a multi-pronged approach to the problem is required, with a long-term commitment and an overarching focus on creating inclusive cultures. While wāhine recognised a genuine commitment by Fire and Emergency to improve their working conditions and to ensure they flourish within it, they are frustrated with the perceived slow speed of progress.

The career experiences of wāhine can be viewed as an important indicator of the broader health of the organisation. When conditions improve for wāhine firefighters, all members of the organisation will likely experience a positive workplace. Identifying and delivering outcomes that can be achieved in the short-term (e.g. career planning advice, making training more attractive, providing ergonomically suitable gear and clothing) will be important while longer-term critical changes that underpin many of the other areas of change needed are progressed (e.g. inclusive and respectful workplace environments with effective and supportive leadership).

… women absolutely can nail being a firefighter, and working all the way up the ranks, absolutely. What I ultimately wish is that there were greater levels of support for women to do it – because we do it anyway without it, but could you imagine how amazing it would be if women were as supported as the guys are, could you imagine the kind of leaders we would have? Truly extraordinary.

(Volunteer firefighter)