Mental health deployment to the 2011 Queensland floods: lessons learned

Katrina Hasleton, John Allan, Garry Stevens, Rosemary Hegner, David Kerley

Peer-reviewed Article

Abstract

| Following a request from Queensland Health for NSW staff to assist in the mental health response in areas devastated by the January 2011 floods, four teams of mental health staff travelled to Queensland for a series of two-week deployments to support their Queensland colleagues in responding to the flood disaster. This was the first time NSW mental health staff have been deployed interstate and the lessons learned from this deployment were derived from the situation reports, participant feedback and an online survey. The lessons include the need for better communication between incoming and departing teams, the pivotal role of team leaders, and the need to use initiative and a flexible approach in undertaking strategic roles to support the emergency response. The aim of this paper is to document the deployment in order to inform future policy and practice. |

Article

Introduction

In January 2011 widespread flooding in south east Queensland required a massive disaster relief operation. Following a series of regional floods which began in December 2010, severe flash flooding, described as an ‘inland tsunami’, devastated communities in Toowoomba and the Lockyer Valley, killing 21 people (ABC News, Queensland Police 2011). Within days the Brisbane River also rose and by mid-January 23 000 homes had been inundated in Brisbane and Ipswich alone. By late January, 35 people had lost their lives (Queensland Police 2011, Brown et al. 2011, Adelaide Advertiser 2011).

Communications between Queensland Health and NSW Health covered a number of requirements and included specific concerns about the immediate needs of children and adolescents in this large-scale disaster. In addition, support of existing mental health services was required as many of the Queensland workers were either personally affected and/or involved in the wider response. A request from Queensland Health for mental health assistance was forwarded to the NSW Mental Health and Drug & Alcohol Office (MHDAO).

Image: shutterstock.com

Brisbane homes under water in January 2011.

At that time flooding was also an issue in northern and western NSW. The NSW State Mental Health Controller requested the then Northern Sydney Central Coast Area Health Service to assemble an initial team of six mental health staff that would include some child and adolescent mental health expertise and a capacity to support adult mental health service delivery.

Subsequently, three further teams were deployed (from the then South East Sydney and Illawarra Sydney South West and Hunter New England area health services) on two-week rotations over a two-month period. Tasking of the four teams changed as the event phase moved from response to recovery, with primary tasks including:

- Psychological First Aid

- mental health assessments

- supporting existing mental health services

- community outreach with Red Cross

- supporting community processes

Image: D. Kerley

Team 3 ready for deployment. L-R: Hayley Conforti (O.T), Alice Maidment (RN EPIS), Tami Suzuki (SW), David Kerley (CNC CAMHS), Andrea Simpson (CNC EPIS).

The then NSW Health Counter Disaster Unit co-ordinated the deployment and took responsibility for logistics, centralised communication, and briefings prior to departure.

Although within-country deployments of mental health staff, either as specialist teams or members of medical/public health teams, have been documented in places such as the United States (North, Dingman & Hong 2000), to our knowledge no disaster-related mental health deployments have previously occurred in the Australian response context.

Disaster mental health preparedness in NSW

Mental health is one of the five major contributing health service components that constitute a whole-of-health response, both at a state and local health district level. Responses are co-ordinated and managed at the local health district level, with support from state-wide resources should local resources be overwhelmed. Recent events highlight the importance of a well-integrated mental health capacity; notably World Youth Day (2008), the Quakers Hill nursing home fire (2011) and airport responses for people returning from the Christchurch earthquakes (2011) (Hasleton, Stevens & Burns 2011, Kwek, Gardner & Howden 2011).

In calling on local health districts to provide teams for this deployment the State Mental Health Controller drew on a system of preparedness across NSW, the elements of which include:

- strong relationships with the NSW Health Emergency Management Unit, State Disaster Welfare Services, and other key stakeholders

- the Mental Health Disaster Education and Training Program

- the Mental Health Disaster Advisory Group which supports the role of the State Mental Health Controller

- the Mental Health Services Supporting Plan, a supporting plan to the NSW Health Services Functional Area Plan (NSW HEALTHPLAN)

- disaster mental health resources which includes a Disaster Mental Health Manual and a number of practice handbooks on specific elements of mental health disaster response (these and other resources are available on the NSW Health Emergency Preparedness website), and

- the Mental Health Help Line which is a 24-hour phone service that can be activated by MHDAO or by the State Mental Health Controller when a mental health line specific to the event is required.

Deployment tasking and transitions

Initial feedback about the deployments was compiled via the deployment co-ordinating team (the then NSW Health Counter Disaster Unit) and MHDAO from situation reports, verbal communications, and operational debriefing processes. Although the anticipated roles had been agreed and briefed, early feedback to the co-ordinating team indicated a lack of clarity about the roles of the first deployed team. A lack of experience with this type of deployment by both the receiving area and the deployed teams appeared to add to this initial uncertainty. The role of the team leader in further briefings and negotiations with local services was paramount in establishing both the first and subsequent teams.

An issue that followed was the changing focus of the deployments over the eight-week period which effectively spanned the early response through to the recovery phase. The nature of the changing roles and related issues facing the teams are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1. Team roles and tasking

|

Team 1 (Jan 17-Feb 2) |

Team 2 (Feb 2-Feb 16) |

Team 3 (Feb 16-Mar 2 ) |

Team 4 (Mar 2-Mar 18) |

|

|

Tasks |

support/assist Crisis and Assessment Team, Emergency Department and mental health team, cover shifts for fatigued staff assist at Ipswich Evacuation Centre and recovery centres community outreach with Red Cross assessments and support for flood related trauma support child care centre staff and parents. |

work with welfare and recovery agencies identify vulnerable groups support ongoing clinical service delivery assess referrals from primary care provide support to community groups, continue to cover shifts for local staff. |

support local staff personally affected by floods continue to cover shifts in local services to replace exhausted staff, and resource and inform local groups and agencies about mental health impacts and self-care. |

presentations and information packages for NGOs deliver resources and education packages for continued use by local agencies and community groups. |

|

Emerging issues |

Lack of definition and multiple roles that changed during the deployment. Major role for team leader in negotiating with local services. |

Trend towards more referrals from primary care. |

Pre-existing local resource/ organisational difficulties apparent. Local staff exhausted. |

Local residents anger at community meetings. |

|

Transition |

Feedback that Team 2 should adopt a flexible approach incorporated into briefing for Team 2. |

Emergency role winding down. Recovery planning not yet implemented. |

Need to respond to changing needs and seek out roles. Handover and briefing for Team 4 not adequate due to timing difficulties. |

Creating exit strategies. |

Post-deployment survey

An email request to complete a confidential online survey was sent to 23 mental health personnel involved in the Queensland flood deployments. The survey was constructed in SurveyMonkey and was distributed via MHDAO in early September 2011—six months after the final full team debrief.

The aim of the survey was to examine the efficacy and outcomes of the deployment in order to inform consideration of future regional or inter-state missions. Respondents were asked a range of open-ended and closed questions about:

- the deployment planning and its management

- the quality of operational briefing/debriefing

- the appropriateness and delivery of their roles and tasking, and

- their recommendations for future mental health deployments.

The survey was completed by 22 of the 23 deployed staff, effectively representing the entire mental health deployment group. Around two thirds of those deployed were female (68 per cent) and over 45 years of age (64 per cent).

Excerpt from report to NSW Health (Team 2)

Two (2) team members are currently working 12 hour shifts (one commencing at 0700 hours and one commencing at 1900 hours) at the Ipswich Hospital conducting Emergency Department mental health assessments.

Team members visited community recovery centres at Fernvale and Esk (one hour north of Ipswich).

Following further discussion with the Fernvale Recovery Centre Team Leader it was agreed to establish a mental health clinic at Fernvale on Thursday. The clinic would serve to assess referrals made by Life Line and other centre staff and provide brief psychological interventions or refer on as required. A flyer for the clinic is currently been made up for distribution by a team member who will be manning the immunisation van at Fernvale tomorrow.

The team is in good spirits.

Planning and management

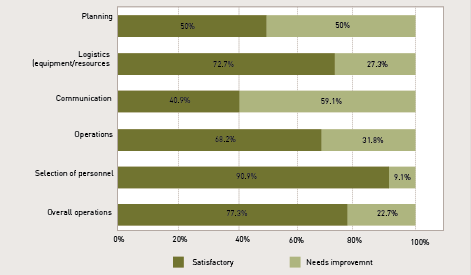

Questions regarding aspects of overall management were rated on a binary scale (‘satisfactory’ to ‘needs improvement’) with the results presented in Figure 1. Most aspects of the deployment were regarded as being satisfactory including:

- selection of personnel (91 per cent)

- overall management (77 per cent)

- logistics including equipment and resources (72 per cent), and

- overall operations (68 per cent).

Areas perceived to ‘need improvement’ related to forward planning for deployments of this type (50 per cent), and communication within deployments i.e. between the deployed team and co-ordinating staff in NSW (59 per cent).

Image: shutterstock.com

Community volunteers clean up in Fairfield, Brisbane in January 2011.

Operational briefing and debriefing

Perceptions of the operational briefing were equivocal with a small majority (54 per cent) agreeing they had been ‘fully briefed on the mission prior to deployment’. The debriefing process was regarded as more effective with 90 per cent of respondents perceiving they had been appropriately debriefed on completion of their assignment.

Respondents indicated that while the operational briefings were generally comprehensive, some information was factually inaccurate or not up-to-date. For example staff were told to take heavier clothing and prepare for wet conditions and possible mosquito activity, which was ultimately not needed. Conversely GPS were needed by several members to travel around unfamiliar areas but were not considered at

pre-deployment.

Roles and tasking

Respondents were generally confident in their professional skills and background training as it related to the deployment task. However, feedback also indicated a lack of role clarity regarding the deployments themselves. Respondents perceived they had the requisite skills for the deployment tasks they undertook (95 per cent), appropriate background training (86 per cent), were given appropriate organisational support to undertake their roles/tasks (82 per cent) and received effective support from their team leader (100 per cent). Around two thirds of respondents (68 per cent) perceived that they were able to perform a useful role within their specific deployment context and that local services and the community saw their role as useful (77 per cent).

Consistent with the noted findings regarding operational debriefing, only 36 per cent perceived their specific roles and tasks were clearly defined prior to deployment (i.e. briefing stage), with 50 per cent perceiving they were clear only ‘to a degree’ and 13 per cent reporting that they were ‘not clear’. Notably, ratings regarding role and task clarity intra-deployment were lower with 27 per cent (‘clearly defined’), 54 per cent (‘to a degree’), and 18 per cent (‘not clear’).

Figure 1. Satisfaction ratings of deployment planning and logistics: mental health personnel.

Future deployments

Respondents made comments about improvements needed for future interstate deployments of mental health personnel. The key issues identified are summarised as:

- Better intelligence is needed at the time of the operational briefing and pre-deployment e.g. inaccurate information about weather and conditions on the ground resulted in inappropriate equipment and clothing.

- Clearer communication between the deploying and receiving agencies would assist transition of personnel to their field duties. While recognising the ‘fluid’ nature of the early response in particular, some receiving teams were unclear about roles and tasking of the deployed teams, which then required active negotiation on arrival.

- Hand-over between teams was often inadequate. This limited timely and comprehensive briefings regarding roles and tasking, organisational structures and key contacts, which could optimise outcomes.

- Greater recognition of the most likely roles at different post-incident phases would be important e.g. support of local mental health services, psychological first aid/support in evacuation centres in early deployments and community education/development in later phases. Mental health tasking in the interim phase may be less clear.

- As the team leader of Team 2 described, ‘we were too late for the crisis and too early for the recovery phase’.

- Workers felt they were often better received and more appreciated by community members when wearing their ‘greens’ (see team photo) and that for some people this provided an opportunity to raise issues or concerns.

Inter-team communication via social media

Respondents were asked whether future deployments may benefit from having a communication link via social media (Twitter or Facebook), particularly between departing and arriving teams. Having such an option available for future deployments was strongly endorsed, with 95 per cent indicating that they would see this as a useful initiative.

Image: M Gebauer

Flooded petrol station at Toowong, Brisbane in January 2011.

Lessons learned

- Mental health roles and expectations: mental health staff deployed following a major emergency must be prepared to adopt a flexible approach, adapt to changing role expectations, and design a response for the circumstances as they find them.

- Education and training programs: mental health workers need a clear understanding of emergency command-and-control structures as well as how the mental health role fits in the whole-of-health response and with welfare agencies. Familiarity with disaster mental health manuals and other resources is essential.

- Vital role of team leaders: previous research highlights that the negotiating skills of the team leader in the local response context may be a pivotal element in successful team outcomes (Stevens et al. 2008). The role of team leaders also includes promoting team cohesion, ensuring the best fit for varied roles for each team member, adapting to changing circumstances, and keeping channels of communication open.

- The importance of briefing teams: mental health personnel should actively participate in the briefing prior to deployment. Briefings should include emergency response elements, supporting core service delivery, and relieving fatigued local staff.

- Handover and communication between teams: communication activities should be built into the planning stage. If circumstances prevent a face-to-face meeting of outgoing with incoming teams, consider telephone contact between team leaders as a bare minimum.

- Impact of uniforms and tabards: staff expressed a lack of comfort wearing uniforms while carrying out community mental health functions. However, in evacuation and recovery centres as the recovery phase began, uniforms provided clear identity and were well-received by other agencies and the public.

- Communication with mental health managers: communication between managers as well as through the central deployment agency would allow for clinical advice and support from within the base service.

- Regular information to family and friends at home: providing clear and regular information provides reassurance and decreases anxiety for those on deployment and their family members. While there may be unavoidable changes in circumstances such as return details, an identified family liaison officer can provide reliable information and reduce undue anxiety for family.

- Manage the impact on teams that remain on standby and/or do not end up being deployed: staff on standby pending a decision to deploy additional teams, need to plan and prepare for work and home absences, and there may be a considerable period of uncertainty. Their contribution should be acknowledged in any post deployment reviews. A comment from one non-deployed team leader was, ‘the willingness to assist and put everything else on hold appears to wane over time’.

- Post deployment: acknowledge teams for their contribution and provide opportunities to review the overall deployment, provide expertise and suggestions to guide future development of mental health deployments.

Conclusion

While mental health responses to such events require a response that is based on the best available evidence, each event presents unique challenges and requires a co-ordinated response tailored to the circumstances. This deployment was provided in response to a request from Queensland Health for NSW mental health staff to help sustain core services and assist with the disaster response. Early challenges about roles and expectations were overcome, with teams undertaking a broader range of roles than had been anticipated.

Future deployments may be enhanced with specific improvement in aspects of communication, planning, and team briefing processes. Broadly however, the knowledge and skills gained from this experience will promote effective future deployments of mental health staff in response to disasters and major adverse events within NSW, interstate and overseas.

References

ABC News, ‘Grantham is a town left in tatters’. 11 January 2011. Archived from original on 26 January 2011. [14 January 2013].

Queensland Police 2011, ‘Death toll from Queensland floods’. [14 January 2013].

Brown R, Chanson H, McIntosh D, & Madhani, J 2011, Turbulent Velocity and Suspended Sediment Concentration Measurements in an Urban Environment of the Brisbane River Flood Plain at Gardens Point on 12–13 January 2011. Hydraulic Model Report No. CH83/11. The University of Queensland, School of Civil Engineering. Brisbane, Australia.

Adelaide Advertiser, ‘Brisbane, Ipswich treading water’. 12 January 2011. [12 January 2013].

National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN) and National Center for PTSD (NCPTSD), Psychological first aid: Field operations guide, 2nd Edition 2006. [12 January 2013].

North, CS, Dingman, RL, & Hong, BA 2000, The American Red Cross disaster mental health services: Development of a cooperative, single function, multidisciplinary service model. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, vol. 27, no. 3, pp. 314-320.

Hasleton, K, Stevens, G & Burns, P 2011, Mental health response for World Youth Day: the Sydney experience. Australian Journal of Emergency Management, vol. 26, no. 4, pp. 48-53.

Kwek, G, Gardiner, S & Howde, S 2011, ‘A firefighter’s worst nightmare’ as multiple deaths confirmed after fire breaks out in nursing home. Sydney Morning Herald, 18 November, 2011.

NSW Health, Disaster Mental Health Manual and Practice Handbooks. NSW Health Emergency Preparedness website.

Stevens, G, Byrne, S, Raphael, B & Ollerton, R 2008, Disaster Medical Assistance Teams: What Psychosocial Support is Needed? Prehospital & Disaster Medicine, vol 23, no.2, pp.198-203.

About the authors

Katrina Hasleton is a Senior Policy Analyst at the Mental Health and Drug and Alcohol Office, New South Wales Ministry of Health where she co-chairs the NSW Health Mental Health Disaster Advisory Group.

Garry Stevens is a Clinical Psychologist and Research Fellow at the Disaster Response and Resilience Research Group, School of Medicine, University of Western Sydney.

Rosemary Hegner is the Director of the NSW Health Emergency Management Unit, Office of the State Health Services Functional Area Coordinator which co-ordinates the whole-of-health response to major incidents, events and emergencies including the deployment to Queensland.

David Kerley was the team leader for team 3 in the Queensland deployment. He has an RN (Mental Health MA(Community and Primary Health) Graduate Diploma (Policy) Clinical Nurse Consultant/Team Leader CAMHS Sydney Local Health District.

Assoc Prof. John Allan is NSW Health Chief Psychiatrist and an Associate Professor at the University of New South Wales. He is the NSW Mental Health Controller under NSW Healthplan.

Correspondence

Katrina Hasleton may be contacted at khasleton321@bigpond.com.