In view of the unprecedented challenges faced by public sector organisations responding to emergencies and reducing disaster risks, this paper identifies some constraints that influence the effectiveness of disaster risk reduction delivery within communities. By using an institutional theory lens, the paper includes explanation on institutional dynamics within the disaster risk reduction organisational field domain and presents conceptual frameworks based on analyses of the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030. The paper also presents initiatives and institutional arrangements that have shaped the resilience discourse within an Australian context. This work is valuable for academics and practitioners seeking to understand theoretical underpinnings of institutional dynamics.

Background

The task of coordinating emergencies and managing risks is often perceived as the sole responsibility of public sector organisations. This is because of the significant role they play in managing risks, responding to emergencies and providing support to affected people (Renn et al. 2011; Twigg 2015). Although, in a recent study by Tasantab et al. (2023), it was inferred that expectations and demands could emanate from both the community as well as from responding organisations. Given the effects of disasters and the complexities and uncertainties presented, there are often expectations that public sector organisations should provide immediate and longer-term solutions (Hagelsteen and Becker 2019).

The Australian Government established the National Emergency Management Agency1 (NEMA) in September 2022 to deal with Australia’s response to emergencies and disaster risk management at a national level across states and territories. Such a reform may present some constraints for the disaster risk reduction organisational field. These constraints include:

- goal ambiguity and structuration

- resourcing

- socio-cultural systems

- communication.

The term ‘disaster risk reduction (DRR) organisational fields’ is used in this paper to encompass ‘the totality of actors and individual organisations with varying goals, values and interests whose statutory functions cut across reducing disaster risk’ (Toinpre et al. 2018a). To examine this concept, an institutional theory lens is used to dissect aspects of institutional dynamics relating to structure and function.

Institutional theory is a powerful explanatory theory used to examine organisational dynamics (DiMaggio and Powell 1983; Cai and Mehari 2015). It examines policy and management issues as well as the interaction between organisations and the influence of actors on their institutional environment (Lawrence and Suddaby 2006; Lawrence et al. 2011). By using qualitative methods built on constructivism, this paper suggests a pathway towards institutional resilience by deconstructing the priorities developed by the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030 (UNDRR 2015). Since institutions act as fulcrums for attaining standards, ethics, norms and policies, the Sendai Framework could be a significant supporting tool for addressing institutional constraints. This approach can be a panacea for inter- and intra-organisational collaboration to improve DRR outcomes. In addition, it may contribute to informed decision-making, commitment, interest and capacity for stakeholders including private and public sector organisations at various levels of governance, especially as Australia is a signatory to the Sendai Framework implementation (Forino et al. 2019; Paton 2019).

Methodological approach: data search, screening and synthesis

Qualitative research involves worldviews, assumptions, the use of theoretical lenses and the study of research problems that inquire into the meaning individuals or groups ascribe to social problems (Creswell and Poth 2016). Using this mode of inquiry, the researcher collects data by reviewing literature (via sources such as books, journal articles, reports), examining documents, observing behaviours or interviewing participants (Patton 2014; Creswell and Poth 2016). This research uses a qualitative method of a 2-stage literature review to provide linkages between institutional theory concepts, institutional dynamics within the Australian context and the Sendai Framework. The first stage involved a traditional literature review on institutional theory concepts guiding the discourse and the second stage involved a critical review (see Table 1) to identify common barriers that might hinder the efficacy of DRR delivery. Document analysis of the Sendai Framework was also conducted to develop and analyse conceptual frameworks guiding the discussion.

Databases such as Scopus and Google Scholar were used to obtain ‘high-impact’ ranking and quality peer reviewed journals published in English. A ‘phrase-specific’ search on Google Scholar using the search string ‘institutional constraints influencing DRR outcomes’ was used to identify common barriers affecting DRR organisational fields.

The initial search generated 76 documents, which were screened and filtered based on relevance, title, abstract, keywords and body text. Of the 76 documents, 24 duplicates were removed using Endnote software, leaving 52 documents for scrutiny. In addition, a search was conducted on the Australian Institute for Disaster Resilience Knowledge Hub and NEMA open-source platforms to access and obtain government published reports. Document analysis is a valuable research approach but can be underused in many instances (Merriam and Tisdell 2016). As a segue into further analysis of the DRR organisational field domain, an analysis of the Sendai Framework (specifically priorities 2 and 3) was conducted. Findings were used to prescribe pathways that address identified institutional constraints.

Table 1: Some common institutional constraints within DRR organisational fields.

| Institutional constraints | Contexts | Authors |

| Goal ambiguity and structuration | Response-based collaborative structures relating to organisational roles/responsibilities. Response in post-disaster support and community recovery. Institutional isomorphism in DRR organisational fields. |

Renn et al. (2011); Schipper and Pelling (2006); Toinpre et al. (2018a); Hagelsteen and Becker (2019); Edgeley (2022). |

| Resourcing | Multi-objective optimisation problems. Resource-based approach for examining disaster risks. Capacity development for risk reduction. |

Hu et al. (2016); Satizábal et al. (2022); Imperiale and Vanclay (2020); Hagelsteen and Becker (2019); Ton et al. (2019). |

| Socio-cultural systems: context, ecological framework and diversity | Indigenous worldviews, knowledge and practices for inclusive DRR. Social learning approaches for ecosystem-based risk reduction. Influence of psychological factors on disaster preparedness. |

Paton and Buergelt (2019); Ali et al. (2021); Paton (2019); Cannon (2016); Murti and Mathez-Stiefel (2019). |

| Communication | Community engagement for participatory emergency management. Design and implementation of early warning systems. Influence of disaster risk communication on preparedness. Design of health and environmental communication programs. |

Fakhruddin et al. (2020); Satizábal et al. (2022); Renn (2020); Abunyewah et al. (2020); Goerlandt et al. (2020). |

Institutional constraints affecting DRR organisational fields

Several issues affect DRR organisational fields. These issues arise from plurality of legitimate viewpoints for evaluating decision-making outcomes (Renn et al.2011), the dilemma of responsibility and delegation among statutory entities (Satizábal et al. 2022), uncertainties in communicating risks to the public (Fakhruddin et al. 2020) and limitations posed by restrictions in knowledge integration in practice (Murti and Mathez-Stiefel 2019). Public sector organisations also deal with multiple conflicting logics, demands and expectations (Twigg 2015; Lounsbury and Boxenbaum 2013; Greenwood et al. 2011). However, community-based risk reduction mechanisms are viable for mitigating such issues when it is a shared responsibility and where participation is guided (instrumental) or people-centred (transformative) (Sufri et al. 2020; Twigg 2015). The following sections explore some constraints affecting DRR organisational fields.

Goal ambiguity and structuration

Uncertainties and complexities have been identified as drivers of change within institutions (Root et al. 2015). However, these elements require the adoption of new or the review of existing processes or structures. This means that, at each phase of dealing with complexities, there will be inter- and intra-organisational challenges that require unique capabilities (von Meding et al. 2011; Ahmed and Charlesworth 2015; Seddiky et al. 2020). Complexities may arise from ambiguity due to varying values and perspectives (Edgeley 2022) as well as the emergence of patterns of homogeneity and heterogeneity due to increased dynamic pressures. Dynamic pressures are the institutional constraints triggered by the interactions between structures and processes leading to unsafe conditions (Twigg 2015). Such pressures could also lead to changes in organisational structure or nomenclature. This was observed in the establishment of NEMA.

Homogeneity and heterogeneity

Institutional theory concepts that provide clarity on homogenisation and heterogenisation are infusion of value, diffusion, and loose coupling. These concepts explain why organisations merge to maintain their functions or fragment to expand functionalities. Homogenisation often occurs when larger organisations need to deal with institutional constraints such as resourcing or duplication of functions while heterogenisation occurs when organisations need to diversify their functions. These could be associated with adjusting to major political or socio-cultural shifts. Infusion of value is based on the need to add significance beyond the existing culture or traditional beliefs (Kessler 2013; Suddaby 2013). In this context, stakeholders will be more inclined to accept new ideals that improve their quality of life and address their expectations and demands. Diffusion is based on the adoption of practices based on social or community values and is subjective to interpretations of the community adopting such practices. Loose coupling explains the ceremonial adoption of practices or processes that are separate from the original functions for which they were established (Kessler 2013; Suddaby 2013). This study views loose coupling in the context of decentralising or expanding a much larger organisation to explicitly address issues within communities (e.g. business franchises, government ministries, departments, government agencies).

Resourcing

Pioneer work on the Pressure and Release Model suggested that progression towards vulnerability is exacerbated by limited access to power, structures and resources (Blaikie et al. 2004). Risk reduction activities are often affected by the limited quantity of resources available and sometimes multiple conflicting interests among stakeholders particularly on how resources should be allocated (Hu et al. 2016). This is acknowledged as a factor exacerbating vulnerability (Ton et al. 2019). Limited resources may also affect public sector funding, job satisfaction, household income or staff shortages (Hagelsteen and Becker 2019). Resourcing in this context may be tangible (e.g. income, production, tools) or intangible (e.g. knowledge, social networks, health, emergency services) that are crucial to the successful delivery of risk reduction outcomes (Ton et al. 2019).

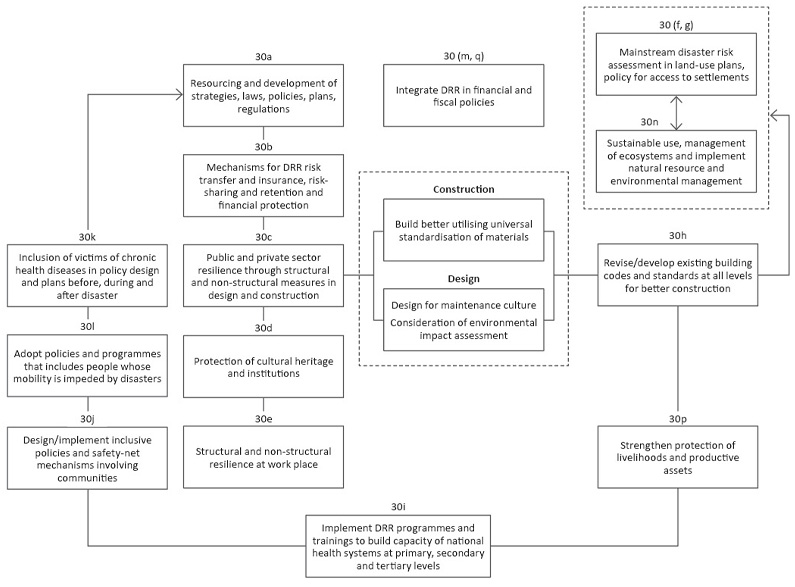

With the increasing effects of climate change across the globe, governments need to choose between avoiding, accepting or transferring the risks posed by events such as flooding, landslides, earthquakes, tsunamis, cyclones, drought and erosion. Prescribed guidelines within the Sendai Framework can be used to develop fit-for-purpose non-structural measures to mainstream risk assessment in land use, ecosystems and natural resource management based on prevailing conditions (especially in the design and construction of critical infrastructure). Deconstructing Priority 3 provides a pathway for DRR organisational fields to implement policies that can address resource constraints. Although the focus of Priority 3 has been viewed from a public-private sector perspective, the authors contribute to the role of ‘academia’ as a stakeholder group by building a knowledge base through exploring the constraints affecting public sector organisations (see Figure 1).

From a public sector organisation perspective, increasing fiscal challenges for investment in risk reduction presents inter-organisational rivalry, especially in the top-down or lateral distribution of resources. This is because of the legitimacy-driven nature of organisations for success manifested through increasing staff strength, expanding operations and achieving DRR targets. Bringing public sector organisation operations together could be crucial for working harmoniously to strengthen institutional functions through collaborative partnerships, knowledge sharing and engagement to address resource constraints (Commonwealth of Australia 2022).

Figure 1: Deconstructing Priority 3: Investing in disaster risk reduction for resilience.

Socio-cultural systems: context, ecological framework and diversity

Successful post-disaster recovery operations are characterised by effective and efficient community-led recovery mechanisms underpinned by existing social (sex, race, gender, wealth distribution) and cultural systems or contexts (i.e. traditions, beliefs, risk perceptions) that influence a community’s level of vulnerability and exposure to hazards (World Bank 2013). These factors also determine a community’s willingness and capacity to contribute to successful risk reduction outcomes as exemplified in Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Christchurch, New Zealand where successful community-based risk reduction outcomes were influenced by stakeholder perceptions, engagement and participation (Walkling and Haworth 2020; Satizábal et al. 2022; Burnside-Lawry et al. 2015).

Ecological frameworks describe the inter-relationships between social structures (ministries, departments and agencies) and processes (policies, legislation and programs) within communities. These can be characterised by competing and often conflicting interests among network organisations due to disconnected policy agendas. Nonetheless, coordinating for resilience may require organisations to align with elements of NEMA’s governance arrangements. The heterogeneous characteristics of communities are often shaped by diversity, which determines the manner within which communities would respond before, during and after a disaster event. It also influences how stakeholders understand risks and act. This implies the crucial need to focus on risk reduction knowledge creation and dissemination (Toinpre et al. 2018b).

Indigenous mechanisms2 for risk reduction have not been widely integrated into the implementation of localised frameworks. As identified by Cresswell et al. (2021), ‘existing environmental management and governance arrangements rarely incorporate adequately Indigenous knowledge, practices, culture and rights and as well equitable distribution of natural resources’. For knowledge to be effectively transmitted across a diverse group of stakeholders, DRR organisational field actors need to communicate in a manner that recognises diversity in community characteristics using local and scientific knowledge.

Communication

In DRR organisational fields, communication is at the heart of every phase of the emergency management cycle and presents challenges for stakeholders in risk governance. These challenges are evident in the dilemma regarding the responsibility of the public to prepare and respond to disasters while contradictorily, the information to be relied and acted on is time-constrained and communities have to depend on states and territories for compliance with top-down directives (Satizábal et al. 2022). This is amidst issues arising from navigating between bureaucracy, information source credibility and other constraints. Communication is significant in preparedness as it is one of the 4 elements of early warning systems after risk knowledge, monitoring and warning and risk response capability (Sufri et al. 2020). It is also important for continuous stakeholder participation and engagement (Ryan and Matheson 2010; Nguyen et al. 2011).

In communities where people have low literacy levels or learning difficulties and disability, it may be difficult for them to understand or act on communicated risks compared to others within the community. Communities with access to contemporary technologies (i.e. remote sensing/GIS equipment) are more likely to better assess, anticipate, communicate risk and possibly act promptly compared to others (Twigg 2015). Institutional change within organisational fields is daunting and often presents mixed views especially when it involves changes in structure, process or statutory function (Twigg 2015). These sorts of changes require constant and clear communication with stakeholders. Capabilities in education, training and risk awareness programs have proven to be significant and viable for knowledge transfer and for providing accurate and reliable forecasts for communities at risk (Abunyewah et al. 2020; Toinpre et al. 2018b).

Pathways to strengthen resilience: deconstructing the Sendai Framework priorities

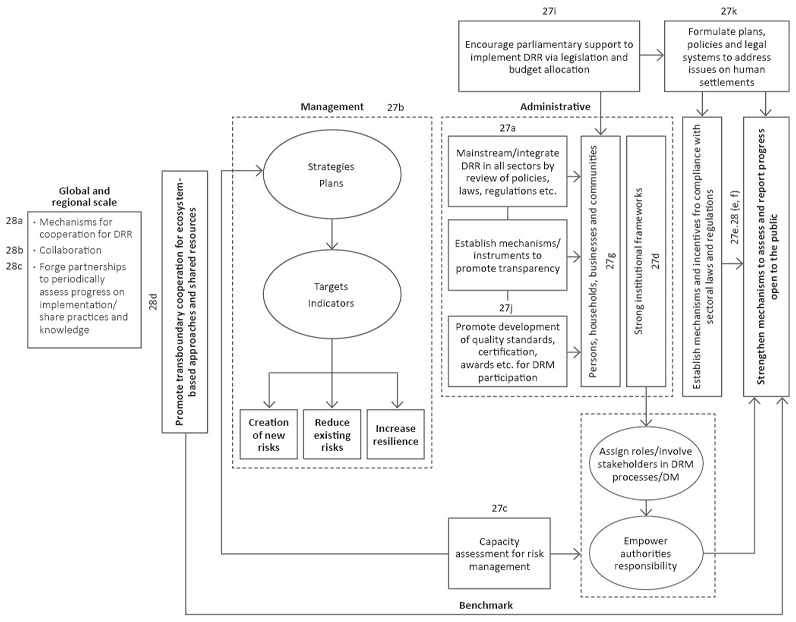

Adapting to institutional change can be challenging. It entails adjusting to new rules, norms, routines or institutional arrangements that may influence how organisations function (see Figure 2). However, effective coordination involves the management of inter-dependencies between individuals and organisations (Raju 2013). Institutional work explains the manner in which institutions are created, maintained, or disrupted (Koskela-Huotari et al. 2016; Willmott 2011). The concept illustrates how individuals or groups manipulate the internal or external functionalities of their institutional environment – an action often described as ‘intentional or purposive’. On the other hand, institutional complexities explain how organisations can deal with complex, contradictory and multiple prescribed logics. The goal of the Sendai Framework involves the implementation of ‘purposive’ inclusive economic, educational, environmental, technological and political policies at various levels of governance. Achieving this entails substantial reduction in mortality as well as complementing actions towards implementation (UNDRR 2015).

The SDFRR Priority 2 is significant to strengthen managerial and administrative functions. The management arm involves the implementation of strategies or plans that are people-centred while aiming to achieve targets and indicators. The administrative arm involves mainstreaming risk reduction in sector frameworks that will aid mechanisms for transparency and the development of quality standards, certifications and awards. In this manner, institutions either passively or actively exhibit normative attributes. With strengthened resilience comes the capacity to improve compliance with laws and regulations, parliamentary support and budget allocation. Through shared roles and responsibilities, strong multi-disciplinary and inter-sectoral networks can be formed. Evaluating the implementation progress of policies, plans and strategies at various levels of governance is crucial for decision-making and actions that support collaboration, cooperation and implementation of shared practices and knowledge. This will help to meet cultural-cognitive, normative and regulative expectations and demands.

Overview of the DRR organisational field domain: an Australian perspective

Australian DRR organisational field domain reforms have been exemplified by the creation of NEMA through a merger with the National Recovery and Resilience Agency and Emergency Management Australia. Table 2 presents some governance initiatives that have shaped the disaster resilience and emergency management policy discourse in Australia building up to this structural reform.

To address institutional constraints, several forward-thinking approaches used to understand the issues that make Australia vulnerable to high-risk hazards have been developed. Some of these are linked to the Sendai Framework priorities (see Table 3) and address 4 areas of:

- understanding disaster risks

- accountable decision-making

- enhancing investment

- governance, ownership, and responsibility (Commonwealth of Australia 2022).

Other bodies operating in this space include the Australia-New Zealand Emergency Management Committee and AFAC, the Australian and New Zealand National Council for fire and emergency services.

These initiatives listed in Table 3 mark the beginning of a major shift from understanding and managing individual hazards to addressing systemic vulnerability, considering future risks in early decision-making and creating options for longer-term risk reduction.

Figure 2: Deconstructing Priority 2: Strengthening disaster risk governance to manage disaster risks.

Table 2: DRR governance initiatives, frameworks and arrangements in Australia.

| Frameworks, initiatives and focus | Year established | |

| National Disaster Risk Reduction Framework | To mitigate and adapt to disaster risks and improve resilience | 2018 |

| National Strategy for Disaster Resilience | 2011 | |

| National Climate Resilience and Adaptation Strategy | 2015 | |

| Australian Government Crisis Management Framework - V1: Stipulate standing arrangements for Australian government’s response to all crisis, including natural hazards | 2012 | |

| Australian Disaster Preparedness Framework: enhance disaster preparedness for effective response and recovery | 2018 | |

| National Framework to Improve Government Radio Communications Interoperability (2010–2020): Promote interoperability between and within jurisdictions of equipment, data and information | 2009 | |

| Disaster Recovery Funding Arrangements: Provide financial support for disaster recovery | 2018 | |

| National Resilience Taskforce: Provide national direction needed for climate and disaster risks as well as improvement of national resilience across all sectors in Australia | 2018 | |

| Statutory emergency management entities | ||

| Natural Disaster Organisation: To support the coordination and training role of the Department of Defence | 1974 | |

| Emergency Management Australia: Coordinate the Australian government’s activities during crises, provide situational awareness to the government and facilitate Australian government assistance to state and territory governments | 1993 | |

| National Recovery and Resilience Agency: Provide national leadership and strategic coordination for disaster resilience, risk reduction and preparedness for future disasters | 2021 | |

| National Emergency Management Agency: Respond to emergencies, assist communities in recovery and prepare Australia for future disasters | 2022 | |

Conclusion and recommendation

The findings presented in this paper indicate that DRR organisational field constraints are often institutional and operational. The institutional aspects (i.e. rules, laws, routines, procedures, hierarchies, risk governance arrangements) influence how the operational aspects (awareness programs, evacuation, search and rescue, early warning activations) manifest. They largely determine organisational field outcomes. Given the complexities associated with emergency and disaster events, there are several frameworks, plans, committees and stakeholders that provide useful information and guidelines. However, a national consideration of the institutional and operational aspects are necessary because managing disaster risk is a shared responsibility. Fundamental questions are ‘Who does what? When should it be done? How should it be done’. The Australian Government Crisis Management Framework (Commonwealth of Australian 2023) has been a step in the right direction and provides useful information (which is inclusive) on the comprehensive view of the Australian Government’s approach to emergency and disaster management.

In the future, there will be a need for the education and training arm of NEMA to address external pressures by sensitising the public in a manner with which NEMA can enhance its perception as a resilience-driven, adaptive and transformative organisation rather than a reactive or emergency-driven organisation. This will address communication gaps. Another issue is centralisation and decentralisation of roles, responsibilities and terminology used across disciplines, which often appears ambiguous. Recovery itself has been acknowledged as an ‘evolutionary discipline’. It is possible that there could be a career-specific pathway that will cover all aspects of the emergency management cycle. In essence, each phase of the cycle could be a discipline of its own. A pathway to achieve this is by integrating academic and industry learning into tertiary institutions.

This study was limited in that it focused on institutional constraints affecting public sector organisations. Examining constraints affecting other sectors could significantly contribute to the literature and strengthen the DRR organisational field discourse. Further research in these areas is recommended.

Table 3: Some Australian resilience initiatives that align with Sendai Framework priorities.

| Sendai Framework priorities | Framework and initiatives |

| Priority 2: Strengthening disaster risk governance for managing disaster risks | National Climate Resilience and Adaptation Strategy Australian Disaster Preparedness Framework Australian Government Crisis Management Framework Australian National Disaster Risk Reduction Framework |

| Priority 3: Investing in disaster risk reduction for resilience | Network for Greening and Financial Systems Coalition for Climate Resilient Investment Blue Carbon Conservation, Restoration and Accounting Program Aboriginal Emergency Management Program |