Warnings aim to empower people to respond to hazards in an appropriate and timely manner in order to reduce the risk of death, injury and damage. An important part of effective warnings is the message.

Research shows there are many influences on people’s responses to warnings, including message characteristics. It is becoming increasingly possible to issue short messages using channels such as social media, hazard apps and cell-broadcast alerting via the mobile network (e.g. New Zealand’s recently implemented Emergency Mobile Alert system). People who issue warnings want to know: how can a warning be written as effectively as possible?

People who receive warnings respond in a variety of ways, according to many factors and influences.1 For example, women are more likely to respond to warnings than men, as are people with dependents, those who have higher self-efficacy (i.e. they believe they are capable of responding), and those with stronger social networks. Observing and understanding the significance of environmental cues, such as the sea receding prior to a tsunami or storm clouds gathering are an influence. Social cues can prompt people to respond, including seeing neighbours prepare, or being aware of transport assistance for evacuation.

The way in which people receive warnings is a factor, including:

- the frequency of message dissemination by the information sources

- the level of detail they contain

- the ability for the alert to disrupt the receiver’s activities

- the equipment requirements.

People’s preferences in accessing channels is also a factor. For example, their exposure to TV, radio, internet, social media and mobile phone usage. The warning message itself can influence responses through content, format, design and accessibility to the receiver.

Situation-specific factors on behavioural response to warnings include whether the person receives the warning message, whether they pay attention to it and how well they comprehend it. Assuming they receive and understand the warning, further influences are their perceptions about the severity of the impending threat that is influenced by their prior experience and proximity to the hazard, their beliefs about the protective action options and their perceptions about the agency issuing the warning (including trust). The action that they take may be to search for further information to fill any gaps in their understanding about the situation. Other situational factors can help or hinder their response, such as physical obstacles or enablers to evacuating, looking for children or pets and helping vulnerable neighbours.

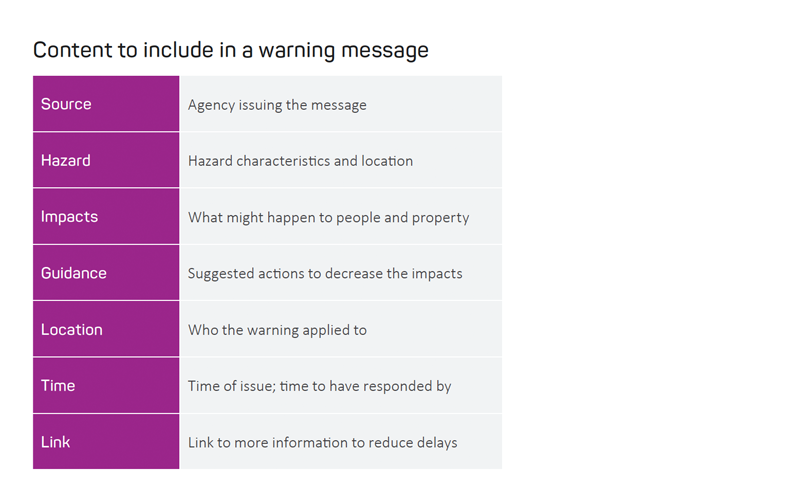

Agencies responsible for warnings can influence these factors so that there is a higher likelihood of an effective and timely response. Ensuring the warning message is optimal is one way to do this. Prior research2 has highlighted the key elements that should be included in a warning message. These are summarised in Figure 1. The optimal order of these elements differs according to the length of the message3, however, it is more important that the message is clear and understandable.

Figure 1. Elements of a warning message

In the context of warning messages up to 1395 characters, longer messages are more effective than shorter messages as they provide enough detail so that seeking more information is minimised. On a mobile phone, having paragraph breaks in text helps make the message easier to read.

A warning message needs to:

- be simple and accurate with no acronyms (including in the source name, unless studies demonstrate that the public understand it)

- be specific enough that people personalise it

- include achievable actions.

If the message is an update, it should say so.

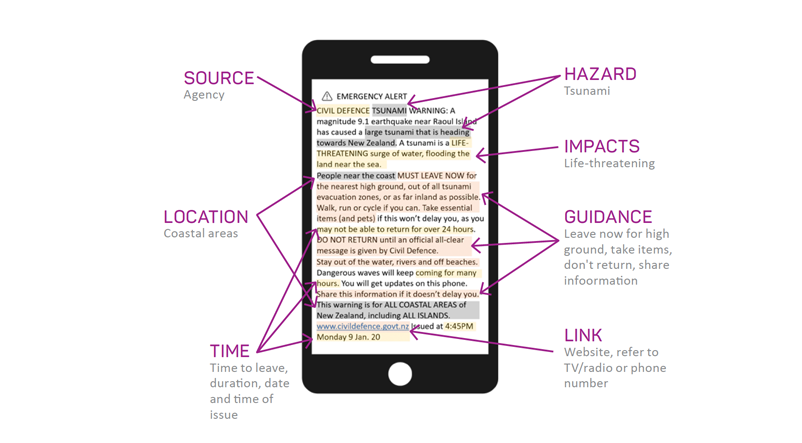

Messages should not use only ALL CAPS because this is perceived as one being shouted at and is more difficult to read. Figure 2 shows an example message and includes the important elements of a message on a mobile device.

Figure 2: Example of short warning message showing key elements shown on a mobile phone.

Guidelines for writing effective short warning messages (Potter 20184) have been used by New Zealand’s National Emergency Management Agency and local government emergency mobile alerts since 2018. The guidelines include templates and examples.

The guidelines are based on evidence from international research and were developed in 2017–18 with a steering group of local and central government agencies who issue emergency mobile alerts in New Zealand. The guidelines were tested in a New Zealand context in 2017 with a sample of public participants (N=28)5. In this research, participants from four locations across Wellington were presented with one of two example emergency mobile alerts about tsunami evacuation. This was to test differences in the guidance messaging and in the format that time was given in relation to their intended actions. Results showed that information about the time should be given in 12-hour format as fewer people understand 24-hour format, however, further research would confirm this. Within five minutes of receiving the message, 86 per cent of participants indicated they would intend to evacuate. However, caution is advised as the sample size in the research was small and not representative of the New Zealand population. Findings highlighted that more education and research is required related to public awareness of tsunami evacuation zones.