This article documents an action research Community-led project with the Merrimans Local Aboriginal Land Council Aboriginal Rangers on the Far South Coast of New South Wales. The Fire and Country Cultural Values Project explored how best to empower Community-led cultural connection that positively influences bushfire management.

The cultural science team in the NSW Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (DCCEEW) is, we think, an Australian first. It is a group of government-employed Aboriginal staff who are supported to practice cultural science. Processes of colonisation have disrupted the sharing of cultural knowledge through family and extended kinship networks. While there has been significant growth in the interest and support for Aboriginal caring for Country practices, work to partner with communities to sustainably regrow cultural capacity and capability remains limited. The Fire and Country Cultural Values Project has led to increases in cultural identity through sharing knowledge; restoring pride, confidence and wellbeing and rebuilding kinship relationships between different communities on the south coast. This has enabled community members to participate in, and provide advice to, bushfire risk management planning to protect tangible and intangible cultural assets.

Position statement

This paper outlines a case study of action research undertaken with the Merrimans Local Aboriginal Land Council (LALC) on the Far South Coast of NSW on Dirringanj Country. The authors acknowledge that the format and writing style used in this paper is that of a traditional academic publication. To influence Western process (as this project aims to do), it is important to communicate in academic journals. However, we need to communicate in both Western and Indigenous ways. To do this, Aboriginal ranger teams are creating paintings as a reflection of their story and journey as part of this project. Beside each painting we display the corresponding scientific papers to demonstrate the different ways of communicating, with both methods respecting the different knowledge systems, but telling the same story.

This paper was written and contributed to by all authors. In some cases, information was provided verbally and transcribed. When cultural knowledge has been provided, it has been referenced or cited using an approach that was developed in collaboration with the NSW Threatened Species Scientific Committee. The approach recognises the significant value of the knowledge held by Aboriginal custodians that has been passed on for generations and should not be considered less than peer-reviewed academic expertise (see Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water Threatened Species Working Group 2024, Appendix A).

Introduction

Historical and ongoing processes of colonisation and discrimination prevent Aboriginal people from carrying out their responsibilities to care for Country.1

A fundamental aspect of Aboriginal place-based relational care, where Country is kin, is the sharing of tens of thousands of years of cultural knowledge through family and extended kinship networks. This practice has been devastatingly disrupted since European settlement and non-Aboriginal people talk of culture being ‘lost’. However, despite pervasive and persistent structural, economic and social barriers, Aboriginal people have continued to practice and share culture. Fundamentally, Aboriginal cultural knowledge is tied to Country, it lives within Country and we believe it can never be lost. Support is needed to regrow cultural capacity and capability.

In recent years, particularly since the 2019 and 2020 bushfires in eastern Australia, there has been a surge in interest and support for cultural land management, particularly ‘cultural burning’ (e.g. Cavanagh 2022; Costello et al. 2021; Wiliamson 2021, 2022; Victorian Traditional Owner Cultural Fire Knowledge Group 2019). Well-meaning research and grant initiatives from government and not-for-profit organisations have abounded. However, we also need to support sustainable regrowth and repatriation of cultural knowledge. This paper explores how to empower Community-led2 cultural connection that positively influences bushfire management. The approach includes how to support Indigenous people to attend government meetings, while also supporting non-Indigenous people to listen and hear what Indigenous people are saying and why. This paper also explores what cultural information products work for the purposes of the community planning and for negotiating in government meetings. To achieve this, there was training in the language and terms used in government meetings and opportunities were provided to reconnect with Country and share knowledge with kin across multiple Aboriginal ranger teams from the LALCs.

Government drivers for change in bushfire management

The Applied Bushfire Science Program (ABSP) within NSW DCCEEW addresses key recommendations from the NSW Bushfire Inquiry3 in 2020 relating to ecosystems, recognition of Aboriginal cultural knowledge and impacts of fire on Aboriginal cultural values (O’Kane and Owens 2020). Specific recommendations addressed include:

- Recommendation 36: Long-term ecosystem and land management monitoring/modelling, improved understanding of ecosystem health and impact of bushfire disturbances.

- Recommendation 19: Quantifying bushfire risk/residual risk and increased research to inform more effective bushfire risk management planning.

- Recommendation 26: Adopting a coordinated approach to the integration of Aboriginal land management practices into bushfire programs.

The cultural science team specialises in partnering Aboriginal knowledge and practices with ecological and bushfire sciences to create meaningful outcomes for people and Country; in many cases, bridging the worldly views of Indigenous knowledge with these sciences (Graham 2008). While definitions vary by practitioner, the cultural scientists do ‘science’ their cultural way to fulfil their obligations to care for Country, share knowledge and build capacity within community and government, while documenting the changes they observe. Sometimes intentionally and sometimes not, they also influence policy and practice change within the agencies and organisations they work with and within. This outcome is often achieved through demonstrating to non-Aboriginal colleagues a different way of being on, caring for and being cared for in return, by Country. The team works to enable cultural and ecological scientific methods to work side-by-side by building trusted relationships and bridging Aboriginal knowledge and natural and physical sciences.

Bushfire risk planning

The NSW Government has established a regional based approach to planning and coordinating bushfire mitigation activities across all land tenures through regional Bush Fire Management Committees (BFMC).4 These committees have representation from land management agencies and organisations that have responsibility for bushfire management mitigation and emergency responses. As such, Aboriginal representation on these committees is through the LALCs. However, despite invitations and an open seat at the table, many BFMC meetings do not have any Aboriginal representation. When members of the Community do attend, they often do not feel culturally safe, do not understand the processes and feel that their views are not taken seriously (pers comm Moore, Jan 2022; Anderson 1999). Others recount the challenges faced in protecting cultural heritage from natural disasters (Lissoway and Propper 1988; Marrion 2016).

The purpose of the BFMC is to create risk mitigation plans by understanding each representative’s capacity and resources to develop shared plans of action and implementation. An objective of this project was to help Aboriginal representatives feel culturally confident and safe at BFMC meetings and that future bushfire risk management planning would incorporate cultural mapping and cultural seasonal indicators. The goal is for management planning to be updated yearly based on environmental conditions and cultural indicators (i.e. wet years/dry years).

Methodology: entwined with place

Our methodology is First Nations-led participatory action research and draws on Indigenous, feminist and emancipatory epistemologies (Chilisa 2020). Together with Community, we developed a collaborative methodology that recognises Country, in this case Djiringanj Country, as the key knowledge holder from whom we learn. In doing this, we follow the lead of Bawaka Country researchers who argue that properly acknowledging Country as the ‘author-ity’ of research is an ethical imperative (Bawaka Country et al. 2016). A goal of this methodology is that the outcomes of this action research are owned and driven by the Community. This approach is akin to the ‘right way’ science of McKemey et al. (2022)

Dirringanj Country

Djiringanj Country is part of the Yuin Nation, which consists of 13 tribes (mobs) on the NSW south coast. On Djiringanj Country are significant places that represent creation stories in Yuin culture and we can see the spirit of these creation stories on Country in people and in the cultural practices. Djiringanj Country, like other parts of the Far South Coast, provide places of connection, teaching, learning and cultural practice. These teachings are through Ancestral and spiritual connection to place, kinship to each other and the songlines that guide us on Country.

We have a culture that is alive and, in the present, connects us to ways of being, who we are, our place and roles as Aboriginal people caring for Country. We are the custodians of Country and through the stories and passing on of knowledge we, as Djiringanj people, are able to sustain a living culture into the future. (Avery 2025).

Approach

The project began in 2021 with a Community-led approach to develop foundational understandings of cultural values and options for cultural land management practices that mitigate fire and enable bushfire risk planning that considers cultural rights. Key personnel to the project are Aboriginal knowledge holders and rangers, Elders and the wider local community to determine their understandings of fire effects on cultural values and to empower Aboriginal peoples' inputs to the fire-planning process. As the project continued, it was identified that existing emergency response to bushfires was a key knowledge and capacity growth area for community.

The Senior Cultural Scientist on the project was a Gurrungutti-Munji-Yuin person, respected knowledge holder and Elder, Graham Moore. When looking at the project scope and intended outcomes it was determined that the project needed to focus on a case study where existing relationships existed. Due to the physical location and community ties of members of the cultural science team, south eastern NSW was selected as the broad location. However, this location covers 7 different LALCs who have representation on multiple regional BFMCs.

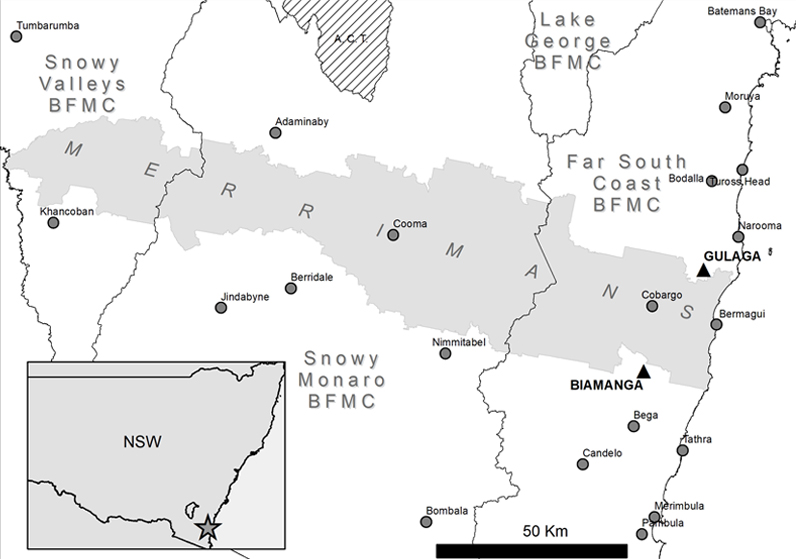

Discussion with Community members led to a decision to focus on Djiringanj Country (see Figure 1) in the area situated between 2 sacred mountains (Gulaga and Biamanga). The area between these mountains consist of Country that supports major movement pathways for Aboriginal people from across south eastern NSW, including inland NSW, who travel for the purposes of ceremony, trade and other cultural practices. These pathways represent a shared space and provide the kinship connection and responsibilities. Exchange of knowledges can be equally shared with all other mobs in the region meaning that as the project grew, responsibility and knowledges can be shared and discovered as one mob.

The Merriman’s LALC was establishing their Aboriginal ranger team and, through engagement with our cultural scientists and this project, we provided operational funds and cultural support for their training and time spent working on this project.

Community-led approach

Consultation with the Board of the Merrimans LALC demonstrated the need for the project to not only support the growth of their new Aboriginal ranger team to become leaders, but to ensure, over time, that the project included the wider community, children and Elders. Maclean et al. (2023) describes the importance of self-determination by Community similar to the way this project is delivered.

Discussions concerning Community data sovereignty were upfront, with agreement that all data and knowledge generated would be stored in a cultural data library, as part of an Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property agreement written into the contract between the DCCEEW team and the Merrimans LALC. The data that has been collected from cultural knowledge (i.e. Traditional Ecological Knowledge, cultural values, cultural indicators) is supported with scientific knowledge at the request of community as they wish to learn from that expertise.

Research questions and project structure

Research questions were developed with Community.

Project questions:

- How can we best support Community to connect back to Country through kinship networks?

- How can Aboriginal culture best contribute to bushfire risk management planning?

Sub-questions:

- How do we support Aboriginal Communities to safely and confidently contribute an Aboriginal perspective into Western bushfire decision-making and planning processes?

- What are the challenges for Aboriginal people to practice their culture in this process/space?

Figure 2 illustrates the project components designed at project initiation by the Merrimans LALC Aboriginal ranger team. The areas in green were designed to enable Aboriginal rangers to contribute to bushfire risk planning. The areas in red are the planning processes that require the representation of Aboriginal engagement for whole-of-government planning. This methodology supports a Community-led approach and allows project components to evolve over time to suit the needs of Aboriginal rangers and, importantly, how Country is speaking.

Each week, 4-5 project team members meet to plan weekly activities and engagements that need to occur. This included setting up a work program for the Aboriginal rangers and managing other non-Aboriginal scientists (including university staff) involved in the program. The non-Aboriginal scientists provided support and partnership on various scientific questions. As at January 2025, there are 35 professionals and scientists who have engaged in on-Country activities, assisting and attending regular weekly or monthly catchups as part of the wider project team.

Figure 1: Location of Merrimans LALC boundary (grey) overlaid with multiple regional BFMC and locations of the mountains Gulaga and Biamanga.

Results: fire and Country cultural values

Drone site mapping

In addition to regrowing and connecting with cultural knowledge, the Aboriginal rangers wanted to increase their knowledge and skills in new technology. Drone mapping was introduced early in the project for 3 reasons:

- it appeals to the Aboriginal rangers (who are young) and they had strong interest in drones

- knowledge holders can no longer access remote cultural sites due to age or health reasons and drone imagery can be provided to Community and Elders so they can immerse themselves in Country, from a sky perspective, to help them reflect on the health of Country and what needs to be done

- there are parcels of land owned by the LALC that need to be treated for bushfire risk management and drones can be used to provide observational records of seasonal indicators, with repeat surveys showing how Country is responding over time to cultural treatments.

Cultural site assessments

This is a key skill for the Aboriginal ranger teams so they can connect with ancestors, understand the Spirit of Country and how Country needs to be managed culturally. The primary law governing Aboriginal heritage in NSW, the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974 (NSW)5, does not acknowledge nor uphold the rights of Aboriginal peoples to govern and safeguard cultural and historical heritage. Consequently, the system often fails to identify and protect significant Aboriginal culture and heritage sites.

Managing and protecting culture and heritage from Aboriginal people’s perspectives involves acknowledging all components of culture and heritage, tangible and intangible, and their interconnections. Aboriginal ranger teams must be able to safeguard and regulate their culture and heritage as a fundamental aspect of self-determination. The cultural and heritage values of a particular location, often referred to as ‘sites’, are determined by the physical evidence of how that site has been used, or is being used, and by knowledge about that place and its relationship to people and other parts of Country.

Due to the nature of this project, the Aboriginal ranger teams walk on Country with knowledge holders and Elders from the project team and also members from Community depending on the subject matter at hand. Due to the kinship relationships with other Aboriginal ranger teams, there also regular opportunities where they are able to share knowledge between themselves.

Figure 2: The Fire and Country Cultural Values Project structure with green circles showing the components designed by Community. The red circles represent the government planning forums to influence. The yellow/brown circle records the journey for learning, sharing and improvements.

Aboriginal land use and fire modelling

Bushfire planning has moved to a risk-based approach using modelling processes. These include showing recorded sites or predictions of cultural assets. However, this is strongly focused on archaeological type information and may not reflect the wider living culture of the values held within Country. The project team created opportunity in the NSW Government technical modelling processes to allow for this type of knowledge to be shared. The team is developing methods to recognise this information within the models so cultural assets and values are assessed transparently along with other assets (i.e. people, property, environment). This means that mitigation methods for cultural values become authorised in government planning process, which should make it easier for Aboriginal ranger teams to obtain funding and insurances to undertake planned works.

Ecological and bushfire science approaches to environmental site training

This component of the project included required training for the Aboriginal ranger teams in Western science methodologies for field sampling of soils, water, plants and animals as well as technologies (computer modelling, photography). Further, training in NSW Rural Fire Service (RFS) regulations and requirements included understanding language, laws and applying for permits, workplace health and safety, attending strategic government planning, fire planning and report writing. From a cultural perspective, training is also about understanding the context of site assessments in terms of other cultural features in the landscape, as well as cultural safety. The aim is to re-discover the existing cultural landscape that was, and still is, present and is now becoming seen and then returning Aboriginal land management mitigation approaches to care for Country (Lake et al. 2017; Pasco et al. 2024; Steffensen 2020).

As the Aboriginal rangers and the ABSP team members developed relationships, the sharing of knowledge grows. This is leading to deep and inspiring dialogue that creates motivation, pride and purpose. Having this shared understanding means the Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal team members can evolve their site assessment to include cultural needs. A common dialogue is that the site training from a Western approach often looks at the subject of interest, monitoring it in great detail, whereas the cultural approach looks at the system through kinship relationships.

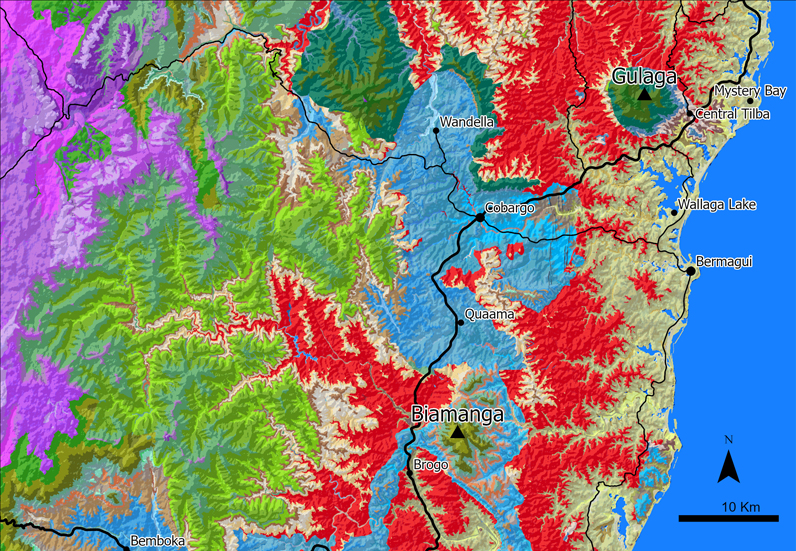

Figure 3: A representation of the dominant types of Country within the study area shown with hill shade from a digital elevation model.

Note: The change in dominant colour represents a change in Country type. The Country type reflects how knowledge holders and Elders interpret Country by recognising soil composition and landscape positions. To reflect this knowledge, a spatial layer of major soils groups and landform features such as ridge tops to lower slopes has been combined. The Country type map is continually refined as field validation occurs on Country.

Cultural values maps

Planning for fire mitigation involves people coming to the BFMC meetings using maps as a common form of language to convey the assets they want to protect. Understanding the use of maps as language and building their own cultural maps gave confidence to the Aboriginal ranger teams to engage in a shared conversation with the committee. We created 3 types of maps:

- Maps that can be shared externally at BFMC meetings that give general information about cultural values.

- Internal maps that provide more detailed information to assist Community to prepare for planning meetings and what information they should share.

- Maps that relate to the seasonal calendar so ultimately the calendar can be represented spatially. This can help communicate where in Country this knowledge would apply. For example, if knowledge was being shared for an area in red (as shown on Figure 3) the knowledge holder could express across tenure that this information can also apply to other parcels of land and, as custodians of Country, they can share conversations about how to work together.

Seasonal calendar

The development of the seasonal calendar is a long-term goal of the project. Huffman (2013) outlines traditional knowledge of Country from around the world and how that should play a greater role in fire management. For the cultural calendar, we will follow an approach similar to McKemey et al. (2021). Its purpose is to provide indicators from Country (McKemey et al. 2020) to guide Aboriginal land management practices that should be implemented and when they should be implemented. This provides evidence for how activities such as cultural fire management can and should be implemented on Country when Country asks. The seasonal calendar approach adds value to the Western approach to determine a fire season but also to outline when they oppose each other and the reasons why. This is particularly important with the challenges of climate change (Metcalfe and Costello 2021) lengthening the fire season (as defined in the Western approach). This is shortening the safe periods for Western-based approaches to hazard reduction. In other words, a seasonal-calendar approach could unlock more opportunities to implement fire in the landscape to care for Country.

The Merrimans Aboriginal ranger team members make observations of seasonal indicators from Country. They record notes of the indicators as well as taking photos of what's happening on Country. They shared those observations with Community members to seek advice and the story of what it could mean for Aboriginal land management decisions. In this way, the whole community is involved in how knowledge is re-discovered. The project team will spatially map the seasonal calendar with data layers such as those represented in Figure 3. The intent is to demonstrate where the knowledge would apply across Country. Thus, when Aboriginal rangers are at the BFMC planning table, they can represent their knowledge and ideas across tenure. For example, they could say: ‘this is what we plan on doing on the land we are responsible for, and this is the same Country that covers your farm, or your national park’. This could open up dialogue about the many options and opportunities for the wider community to care for Country together.

Recording the journey

This Community-led project evolves at a pace that Community and Country are ready for and as new learnings are revealed and developed. To tell the story of this project, it was necessary to record the journey with and for everyone involved (yellow/brown circle, Figure 2). This is done through observation and reflection, testimonials, interviews, videos, photos, cultural storytelling and creation and paintings. The multiple methods are This Community-led project evolves at a pace that Community and Country are ready for and as new learnings are revealed and developed. To tell the story of this project, it was necessary to record the journey with and for everyone involved (yellow/brown circle, Figure 2). This is done through observation and reflection, testimonials, interviews, videos, photos, cultural storytelling and creation and paintings. The multiple methods are opportunities to include everyone and to reach varied audiences, depending on the communication style that suits them best. Culturally, the most effective way to share is through cultural exchanges and gathering. In particular, focusing on the core values of Community for the issue at hand (Ridges et al. 2020).

Kinship connections

This project provides opportunities to reunite kinship. One example was a cultural exchange to Rick Farley Soil Conservation Reserve that was the turning point for this project. Rick Farley is close to the Lake Mungo National Park in south western NSW in rangeland Country. The Rick Farley cultural exchange took place in October 2023 to highlight the connection to Country via pathways and people’s roles and responsibilities. This was a very important part of the training component for the Aboriginal ranger teams where they could connect spiritually as well as physically. Attendees undertook a personal journey of positive cultural discovery; a reward, a rekindling. The ancient lands taught and are still teaching. The meeting on Country with a knowledge holder and an Elder gave the respect that set the theme for the camp. This was not just a physical knowledge gathering but occurred on levels that everyone could take back to their Country; a spiritual awakening for most, a new strength and resilience. The Elders and non-Aboriginal members of the group found it incredibly rewarding to watch the young people grow in many positive ways. Many kinship systems across NSW remain vibrant and active (Rose et al. 2003).

Representatives from the Merrimans, Batemans Bay and Bega Aboriginal ranger teams, the DCCEEW cultural science team, ABSP team, Elders and knowledge holders on Country at Rick Farley Soil Conservation Reserve in 2022.

Image: Graham Moore

Land council fire planning

All LALCs hold various parcels of land and each comes with different fire risk responsibilities. These could be people, property, public assets and infrastructure, the environment and cultural assets and values. For this project, the Merrimans Aboriginal ranger team worked on 2 different parcels of land to determine approaches to return the cultural landscape (as the land is very degraded) while managing the bushfire risk.

Aboriginal engagement in bushfire planning

Revitalising the kinship relationship in the area between the many LALC Aboriginal ranger teams across south eastern NSW is creating the confidence and unified voice to provide representation in the BFMC process. The BFMC non-Aboriginal members are able to understand better ways to engage and provide a culturally safe place for respectful dialogue. In essence, capacity building for BFMCs to understand cultural assets and values as well as Community knowing what information to take to planning meetings and who and when to express that knowledge, so it is effective and listened to.

Results: project outcomes, evidence from 2 case study examples

Indicators of early achievement of the project: inclusion of cultural values in bushfire management

In the early stages of this project, we experienced 2 wider outcomes due to the growth in relationships and trust that were created between the BFMC and the south coast LALC communities. Examples are the Cooma North Ridge and the Cultural Incident Management Exercise to explore the inclusion of cultural assets and values.

Cooma North Ridge

Through this project a new partnership in bushfire management emerged between the Merrimans Aboriginal rangers and the Snowy Monaro BFMC. Cooma North Ridge is a lightly forested ridge line in Cooma that neighbours a significant section of the town. Two works were proposed to reduce the bushfire risk to the neighbouring houses and people. The first, to widen the tracks to allow larger firefighting machinery safe access under emergency conditions (safer standards) and, second, a prescribed burn to reduce fuel loads.

The Cooma North Ridge is known by traditional knowledge holders as an Aboriginal transitional pathway that remains in use today by the local and broader community. The current walking tracks and vehicle tracks are on these pathways. Multiple sites of cultural artefacts have been found in the area where the proposed mitigative works were due to be undertaken. Partnership between the Aboriginal rangers, NSW RFS and Fire and Rescue NSW (FRNSW) led to the following positive outcomes.

Mitigative objective: widening of fire trails

The general areas of the cultural asset were identified on works maps and the Aboriginal ranger teams supplied and installed 2 steel posts about 10 metres either side of each identified cultural asset. Posts were sprayed with red and yellow paint so machinery operators would know not to conduct soil conservation works within this zone (Red - stop works, Yellow - continue works). An inspection of 5 planned turnaround bays occurred, and cultural assets (scatters) were identified. If they were found, they were removed away from the works area.

Mitigative objective: prescribed burn

Given the identification of the cultural assets, the draft prescribed burn plan outlined the general location of the sites and where to keep fire intensity low, if possible. It was recommended this could be done by implementing initial ignitions on these sites before the larger areas were treated via hazard reduction measures and that initial ignitions were conducted by the Merriman Aboriginal rangers. A pre- and post-cultural assets monitoring plan was included so all participants could learn from the exercise through an action-based research approach.

The method allowed a quick and easy solution by liaising and partnering with the Aboriginal ranger teams (as traditional custodians) to ensure the planned works for Cooma North Ridge included cultural considerations without delays or excessive additional costs. Without engagement, the protection of cultural assets would have led to 100 metre exclusion zones making the planned mitigative works difficult to implement.

The engagement of the Merrimans Aboriginal rangers goes beyond current protocols and is testimony to the success of the work to build cultural safety and trusted relationships between the local community, NSW RFS and FRNSW. The teams were able to work together, and modifications were made to the planned activities to allow a mix of cultural and prescribed fire management to take place to ensure asset protection goals were met without damaging cultural sites.

Incident Management Exercise to explore the inclusion of cultural values, South Coast NSW

Following the success of the Cooma North Ridge project, the BFMC members and project team discussed opportunities for the Aboriginal rangers to be included in the control room during a bushfire emergency to provide information on cultural assets and values. To achieve this aspirational goal, significant investment was needed to build deeper relationships and a shared understanding of the significance of protecting cultural sites and Western bushfire management. Training was needed so agency staff and the Aboriginal rangers could learn how to communicate and share the right knowledge at the right time in the right way so quick decisions could occur. Eriksen and Hankins (2014) reported on similar approaches when integrating Indigenous knowledge into firefighting on the ground.

The Cultural Incident Management Exercise occurred in November 2024 and was the first of its kind to bring Aboriginal rangers into the incident control room to experience being involved in the fire management decision-making process. The exercise demonstrated the importance and benefits of ensuring there are cultural custodians present or available who can provide advice to personnel in an emergency response situation. The aim was to consider alternative methods and resource deployment to protect cultural values as well as strengthen relationships between government authorities and the Community. The exercise was attended by 7 Aboriginal ranger teams from south east NSW that were brought together through kinship relationships. These relationships were reinvigorated through this project. In total, 25 Aboriginal rangers attended as representatives of their kinship to Country and its people.

Conclusions

The NSW Bushfire Inquiry 2020 recommendations to include Aboriginal knowledge in decision-making and planning provided the authorising instructions for agencies to interpret how this can be done. Agencies, when responding to changes in the way they undertake business, often create top-down processes for rapid and expansive change. The NSW Government provided this opportunity to explore how we can achieve this (for cultural values and assets) from a grass roots approach. For Aboriginal peoples, this means Community-led (at the pace of the people and Country) and empowering co-design approaches to bring the strengths of the traditional knowledge alongside science-based approaches.

Although it is still early in this project and some aspects (e.g. the seasonal calendar) are longer-term goals, the project team sees the responsibilities of this project’s objectives as a longer journey. The project provides opportunities for relationship development between government agencies and Community. The NSW RFS and NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service have expressed the desire for DCCEEW to support more LALCs and BFMC, given the project's successes to date. Through this trust, people's hearts and minds are opening to explore and try new ways to understand how we can protect the cultural values and assets of Country. The shared learning is what the participants are proud of, regardless of their identity. This is the important to sustain the transformational change we are creating through this project.

Testimonials

As a young generation Elder reflecting on growing up in the old ways talking about land and Country and being taught our ways, this project is providing opportunities to teach the younger generations coming into the future, bringing together all the circles of old ways and new ways. The Elders and knowledge holders have kept this journey going and we always need to keep them present, because they amplify our cultural ways on this project.

Mandy Foster Gamilaroi / Yuin Merrimans Local Aboriginal Land CouncilThe integration of teaching and on-Country learning is what will give this project longevity. It’s all the behind the scenes work that makes this project successful and that is what will set the foundations for a legacy for all our communities.

Blann Davis Wodi-Wodi CEO/ Merrimans Local Aboriginal Land Council