Introduction

This report documents learnings for working effectively in partnership on cultural fire, drawn from the on-Country1 experiences of the Department of Fire and Emergency Services (DFES) Cultural Fire Program (CFP). The CFP is based within the Karla Katitjin Bushfire Centre of Excellence2 on Bindjareb Boodja (Country), located approximately one hour south of Boorloo (Perth) in Western Australia.

Since its establishment in 2020, the CFP has worked towards 3 strategic objectives:

- To collaborate with partners to facilitate two-way learning to build capacity to undertake and support delivery of cultural burning across Western Australia.

- To enable First Nations Australians to develop, implement, coordinate and promote existing and future cultural fire programs and activities.

- To promote sector and community understanding and awareness of cultural fire.

Over the last 3 years, the CFP has been fortunate to have been invited onto Country by Elders to participate in, and support the undertaking of, cultural burns. Importantly, many of these cultural burns signified a ‘return to Country’, where, due to the multi-generational effects of colonisation and resulting injustices, Elders and traditional custodians have not undertaken cultural burning on their ancestral lands for many decades.

Cultural burning ‘connects the next generation with their Country, maintains cultural obligations and traditional stories, and is an expression of custodial responsibility and cultural continuance’ (Standley et al. 2022). A return to on-Country burning can enable traditional custodians to re-engage with cultural practices, share cultural knowledge, meet cultural obligations to Country and exercise their right to self determination (McKemey et al. 2021). Maclean et al. (2018) recognised significant co-benefits of cultural burning and Costello et al. (2021) state: ‘Cultural land management is an essential part of creating well-prepared and resilient communities and landscapes anywhere in Australia’.

While collaboration between government agencies and First Nations peoples in Australia is growing, there remains many barriers (Costello et al. 2021). Barriers identified through Australian-based research identify a lack of fundamental understanding by non-Indigenous organisations on how to effectively collaborate with First Nations Australians (Sithole et al. 2021) including limited knowledge and awareness of governance structures (Russell-Smith et al. 2022) and engagement protocols (Woodward et al. 2020). Cultural fire programs may assist in moderating these barriers and provide opportunities for the public sector to develop deeper understanding about cultural burning while influencing positive change in public sector practice, including greater willingness and capability to listen to, and engage with, First Nations Australians (Freeman et al. 2021).

Goreng-Menang Elder, Uncle Eugene Eades, said following the first cultural burn in over 60 years on Nowanup Boodja:

In the spirit of true reconciliation, we’ve got to make a step towards one another and make some of the wrongs right again. That was achieved in a big way. It was a long time overdue.

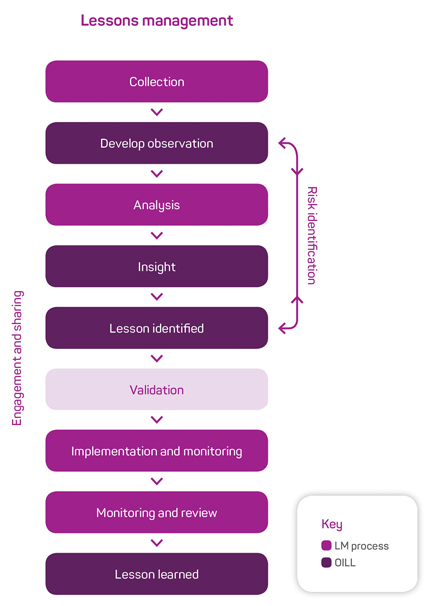

This report describes the application of a formal lessons management approach, aligned with the Australian Institute of Disaster Resilience framework (AIDR 2019), to the CFP and the on-Country activities. To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first time that the AIDR lessons management framework has been applied to a cultural fire program in Australia. The lessons identified here may help individuals, agencies and organisations develop and maintain culturally informed and appropriate methods of engagement to create a culturally safe, respectful and equitable foundation for cross-cultural collaboration.

Methodology and results

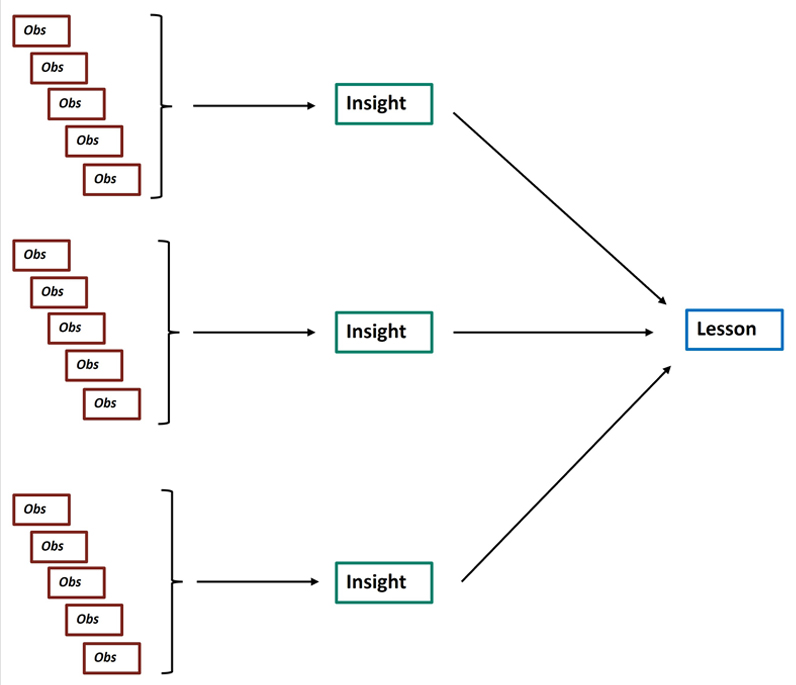

The CFP has applied the ‘Observations, Insights, Lessons Identified, Lessons Learned’ (OILL) methodology as described in the AIDR Lessons Management Handbook (AIDR 2019). Figure 1 shows the OILL process as a structured, replicable methodology that enables large amounts of data and information to be distilled into key messages.

Figure 2 shows how lessons are based on multiple pieces of evidence (observations) that can be grouped into insights that, in turn, can point to a lesson identified.

Figure 1: Elements of a lessons management process (AIDR 2019).

Figure 2: Visual depiction of the OILL process from many observations that can be grouped into insights that create one lesson.

Data collection and observations

For the CFP lessons, observations were collected from events, including training courses, workshops and on-Country activities. Observations were sourced through debriefs, interviews, quotes and personal reflections of Elders, participants, staff and observers involved. Where possible, observations were structured against the elements of a ‘good’ observation (AIDR 2019) and distributed back to those who provided the raw data to check for accuracy and to avoid misinterpretation.

Between May 2022 and March 2024, a total of 547 observations were collected. These were sourced from 14 separate events (n=475) and general reflections on program delivery (n=72). DFES staff contributed 67% of the observations (n=368).

Coding and analysis

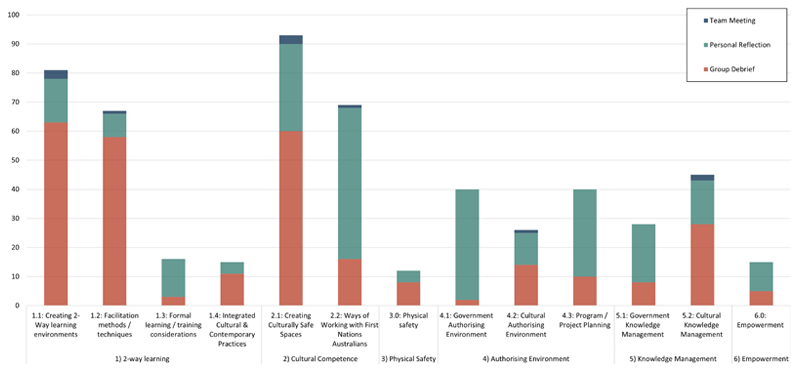

A tailored coding framework was developed for the cultural fire observations with support from Dr Christine Owen, University of Tasmania. The final coding framework, comprising 6 primary and 13 secondary themes, is shown in Table 1. All observations were allocated a primary and secondary code in March 2024. A breakdown of coding results is shown in Figure 3. The primary codes most frequently assigned were Two-way Learning (n=179, 33%) and Cultural Competence (n=162, 30%). Observations were also notably present in Authorising Environment (n=106) and Knowledge Management (n=73). The primary collection methods for observations were debriefs (n=286, 52%) and personal reflections (n=250, 46%).

Table 1: Tailored coding framework for CFP.

| Primary theme | Secondary theme |

| 1) Two-way learning | 1.1: Creating two-way learning environments |

| 1.2: Facilitation methods / techniques | |

| 1.3: Formal learning / training considerations | |

| 1.4: Integrated cultural and contemporary practices | |

| 2) Cultural competence | 2.1: Creating culturally safe spaces |

| 2.2: Ways of working with First Nations Australians | |

| 3) Physical safety | 3.0: Physical safety |

| 4) Authorising environment | 4.1: Government authorising environment |

| 4.2: Cultural authorising environment | |

| 4.3: Program / project planning | |

| 5) Knowledge management | 5.1: Government knowledge management |

| 5.2: Cultural knowledge management | |

| 6) Empowerment | 6.0: Empowerment |

Figure 3: Observations sorted by coding framework (x axis) and collection method (legend).

Developing insights

Insights are developed by grouping similar observations to elicit recurring themes. Applying the coding framework (Table 1) to the observations and producing graphs and tables aids the analysis required to group the data. A total of 91 insights were finalised in May 2024.

Developing lessons identified3

To mitigate potential biases in lesson consolidation, the process transitioned from individual analysis to a group-workshop approach. Following a group workshop, and a process of refinement and internal review in September 2024, a total of 23 lessons were identified from the 91 insights and 547 observations.

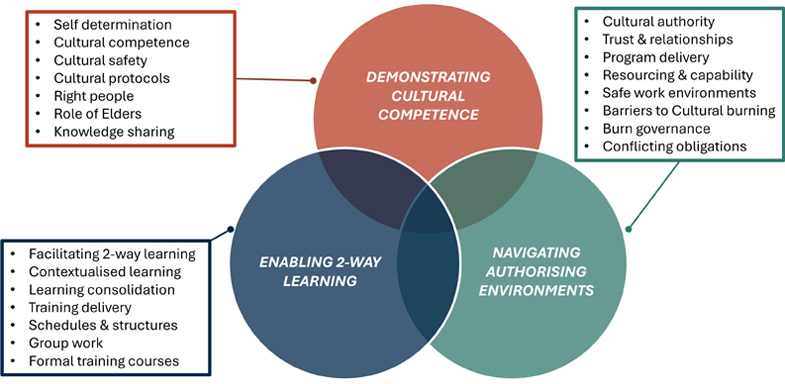

Across the 23 lessons, 3 overlapping focus areas emerged, as shown in Figure 4:

1. Enabling two-way learning (7 lessons).

2. Demonstrating cultural competence (7 lessons).

3. Navigating authorising environments (8 lessons).

4. The key message for each lesson is shown in Table 2.

Table 2: Key messages for the 23 lessons.

| Focus area | Lesson # | Lesson title | Key message |

| Focus Area 1: Enabling Two-way Learning | 1 | Respecting and recognising two-way knowledge sharing opportunities | To maximise the effectiveness of cross-cultural collaborations, two-way knowledge sharing opportunities need to be identified, prioritised and facilitated. |

| 2 | Appropriate training delivery methods | Training and capacity building methods that are experiential, repetitive and rotational will likely be more effective for knowledge creation and retention. | |

| 3 | Contextualised learning | Contextualising training content to settings that are relevant and familiar to participants will enhance learning outcomes. | |

| 4 | Adaptable training schedules and structures | To cater for different learning needs, facilitators need to ensure learning schedules and structures are flexible and adaptable. | |

| 5 | Recognising and adjusting to participant cues and feedback | To maximise participant engagement, facilitators need to be able to recognise participant cues and feedback and make adjustments in real time. | |

| 6 | Group work and group structures | Structure and arrangement of small groups will influence how people interact due to cultural, social and community dynamics. | |

| 7 | Recognising opportunities to consolidate learning | Facilitators need to recognise and act on opportunities to consolidate learning to support participants gaining greater depth of knowledge, experience and competence. | |

| 8 | Considerations for formal training courses | When delivering formal training programs, facilitators may need to adjust typical delivery methods (to facilitate two-way knowledge transfer) and assessment methods (to enable demonstration of competence) | |

| Focus Area 2: Demonstrating Cultural Competence | 9 | Cultural competence | To ensure cross-cultural collaborations are respectful and meaningful, non-Indigenous people need to develop and demonstrate cultural competence. |

| 10 | Cultural communication and engagement protocols | Aligning to cultural communication and engagement protocols will generate better results when working with First Nations Australians. | |

| 11 | Cultural protocols - the role of Elders | Elders play very important roles when engaging, planning and delivering with First Nations organisations and their participation is critical to ensure success. | |

| 12 | Cultural protocols - the right people | Ensuring you are connecting with the right people is critically important for culturally safe and effective engagement with First Nations people. | |

| 13 | Cultural safety | The extent to which First Nations people perceive an environment to be culturally safe will have a significant influence on their level of participation and engagement in cross-cultural collaborations. | |

| 14 | The importance of cultural knowledge sharing | Sharing of cultural knowledge, including across generations, is very important to First Nations Australians and this can be supported through cultural burning. | |

| 15 | Prioritising principles of self determination | To be culturally relevant, meaningful and effective, government programs need to ensure principles of self determination and empowerment for First Nations Australians are a primary priority. | |

| Focus Area 3: Authorising Environments |

16 | Adhering to the cultural authorising environment | To facilitate First Nations self determination and empowerment, government programs should embed cultural governance and authority at the core of direction setting and decision-making processes. |

| 17 | Building trust, reputation and relationships | Effective cross-cultural partnerships are underpinned by strong working relationships which are built on trust, respect and investment over time. | |

| 18 | CFP delivery considerations | To deliver effectively, the CFP needs to plan diligently yet maintain flexibility, while meeting the needs of our authorising environment. | |

| 19 | CFP staffing and capability considerations | To be effective, the CFP requires staff with a diverse skillset, emotional intelligence and a willingness for continuous learning. | |

| 20 | Creating safe work environments | Creating safe working environments is critical, including risk management and consideration for organisational policy and procedure. | |

| 21 | Barriers to cultural burning | To enable cultural burning initiatives, cultural fire programs need to understand and actively address social, economic, legal and political barriers that can prevent participation for First Nations people. | |

| 22 | Adhering to best practice burn governance | Effective and appropriate risk management requires cultural fire programs to adhere to best practice burn governance when supporting planning, preparation and delivery of cultural burns. | |

| 23 | Respecting and managing conflicting obligations | First Nations people working in cultural fire programs can experience conflicting obligations and commitments across cultural and government settings. |

Figure 4: The 23 lessons identified were organised into 3 focus areas.

Validation of lessons by subject-matter experts

Validation of lessons by subject-matter experts ensures that lessons are accurate, relevant and suitable for implementation (AIDR 2019). Additionally, and significantly, this process is critical to ensuring the appropriate management of cultural knowledge. Respected cultural knowledge holders and experts in cultural burning were approached in December 2024 to review the lessons summaries and provide feedback. The purpose of the validation stage in the cultural fire lessons work was so that lessons:

- respected the intellectual property rights of First Nations Australians

- were presented in a culturally safe and respectful manner

- were accurate and aligned with experience of others.

Findings from the validation process were compiled from written feedback and a group meeting held in February 2025. Importantly, validators agreed that learnings were presented in a culturally safe and respectful manner and were aligned with personal experiences of cultural fire initiatives. Validators also identified opportunities for improvement aimed at framing and contextualising the lessons with real-world examples to assist in practical implementation. These opportunities for improvement have been actioned in the following discussion section.

Discussion

Lessons in practice – Case Study One

In May 2023, the CFP was invited to participate in a cultural burn by Goreng-Menang Noongar Elders on Nowanup Noongar Boodja, undertaken in southwest Western Australia. Burn delivery was led by Goreng-Menang Noongar Elders to achieve a range of Elder-determined cultural objectives and was supported by the CFP plus research and not-for-profit organisations. The burn followed a previous cultural burn in 2022 that involved similar stakeholders and was the first time in over 60 years that Noongar Elders had applied cultural fire to Nowanup Boodja.4 Table 3 and Figure 5 show the 3 lesson focus areas illustrated during this on-Country activity; providing a practical example that may be useful to individuals, agencies and organisations undertaking cultural fire programs.

Lessons related to Focus Area 2: Demonstrating Cultural Competence suggest that non-Indigenous people need to demonstrate culturally informed and competent approaches to build relationships. This can underpin meaningful and respectful engagement with First Nations peoples and organisations. This might include an understanding of engagement protocols (e.g. the importance of invitations – Lesson 10), ensuring Elders are appropriately involved (e.g. when speaking on behalf of a community – Lesson 12) or creating culturally safe spaces (e.g. enabling safe passage for visitors to Country – Lesson 13). While there are recurring principles and protocols across different Country and communities, central to cultural competence is appreciating that there are nuances and differences and seeking to understand these is important.

Consideration of the cultural authorising environment is critical and significantly overlaps with Focus Area 2: Demonstrating Cultural Competence. Cross-cultural engagements often see 2 governance systems operating as different ways of knowing and doing that run in parallel on the same project. These are the government way and the cultural way (Russell-Smith et al. 2022). Sithole et al. (2021) suggest that agencies should ask First Nations communities ‘how do we connect with your structures, and how do you want us to work with you?’ rather than imposing their own agency governance structures. Typically, agencies often rely on their own internal governance arrangements (e.g. committees or working groups) that can lack legitimacy for First Nations peoples (Russell-Smith et al. 2022). Such arrangements can become barriers to collaboration.

While acknowledging the need to respect parallel governance structures, Focus Area 3: Navigating Authorising Environments reinforces that it’s critical for government programs to consciously operate within internal governance policies and procedures, particularly for risk management and health and safety matters. Failure to do so can compromise program reputation, ‘license to operate’ in a government context, resource efficiency and the creation of culturally and physically safe working environments.

Table 3: Demonstrated examples of the lessons focus areas in practice (linking to Figure 5).

| Focus area | First Nations example | Government / agency example |

| Focus Area 1: Enabling Two-way Learning |

The First Nations ranger team are learning about integration of cultural and contemporary methods (e.g. different ignition patterns) and equipment (e.g. wogga (hessian) bags and knap sacks). | Agency staff are learning about cultural knowledge, how this is applied and the benefits of knowledge connection and transfer. Agency staff are learning about cultural protocols. |

| Focus Area 2: Demonstrating Cultural Competence | Cultural knowledge is being shared across multiple generations of Noongar families. Noongar Elders have created a culturally safe environment by welcoming visitors. |

Agency staff are respecting the space for Elder led decision-making and direction. Agency staff are acting in accordance with Elder led directives (e.g. exclusion of fire from sensitive or important areas). |

| Focus Area 3: Navigating Authorising Environments | Noongar Elders are exercising cultural authority by determining cultural objectives and overseeing burn delivery. Elders have invited Noongar traditional custodians and non-Indigenous agency representatives to work collaboratively. |

Agency staff provided guidance on adhering to relevant approval processes and planning requirements. Fire agencies have contributed contemporary methods, knowledge and resources to manage burn delivery risks and spread of fire (e.g. mineral earth control line). |

Figure 5: Cross-cultural collaboration while commencing a cultural burn at Nowanup in May 2023.

Image: Peter Galvin, DFES

Lessons in practice – Case Study Two

The CFP delivered 2 bushfire training courses to Danju Rangers in October 2022 and a further one to the same group in September 2023. The purpose of the training was to develop practical skills and knowledge in fire management for the ranger team. The 3 courses are roughly equivalent to the minimum requirements for volunteer firefighters in Western Australia.

In 2022, the courses were delivered using standard fire training delivery approaches with a heavy focus on theory (written training manuals, presentations) delivered in a large training room using largely one-way communication between trainer and trainees with limited practical activities that were undertaken in an urban / built landscape ending with written competency assessments.

Following the 2022 course delivery, the team carried out a debrief to identify opportunities for improvement. While all course participants passed their assessments, it was felt that the standard training delivery approach did not maximise learning outcomes for the ranger crew and adjustments could be made to improve the participant experience, their levels of engagement during the training and the retention of learning outcomes.

Figure 6: Fire training undertaken with Danju Rangers using traditonal delivery methods (first and second image, 2022) and adjusted delivery methods (third and fourth image, 2023).

Images: Pyay Chan, DFES (first and second image), David Windsor, DFES (third and fourth image)

In September 2023, the CFP team was grateful to be invited to deliver further training with Danju Rangers. This time, significantly adjusted delivery methods were used. Training was delivered over 2 days while camping out on-Country and activities focused on creating immersive, experiential learning environments (including multiple small burns), prioritising two-way learning principles, providing opportunities for rangers to lead different sessions and using a range of assessment methodologies. Figure 6 visually compares the differences in training approaches taken from traditional training to on-Country activities.

Through post-training debriefs, the participant experiences and learning outcomes of the 2023 training were significantly enhanced due to the adjustment of training delivery methods. Danju Rangers noted better knowledge retention, greater confidence, improved facilitator and participant interactions and enhanced teamwork. Feedback from the rangers was that this led to a more satisfying and enjoyable experience and, ultimately, a more effective learning environment.

The adjustments made in 2023, and the improvements in outcomes, are directly attributable to a learning culture and iterative refinement of the program delivery.

Importantly, these learning outcomes have been applied to further fire training initiatives such as the Southwest Cultural Burning Project which brought together multiple First Nations ranger teams to enable cultural burning. Participant feedback from fire training delivered by the CFP in 2023 highlighted the value arising from application of the lessons drawn from the Danju experience:

Communication between trainers and trainees reflected a ‘conversation’ style. People were asking questions, bringing others into the conversation, working off each other, discussing things, sharing ideas; it was like a big brainstorm! This style worked well; it was engaging, inclusive and demonstrated everyone had valuable knowledge that can be shared with others.

A range of factors are required for successful two-way knowledge sharing: trust with knowledge holders (Woodward et al. 2020), acknowledgment that different knowledge systems have equal value (Muller 2012) and the need for non-Indigenous peoples to shift from ‘resistance’ or ‘scepticism’ of cultural fire knowledge to a willingness to learn new things (Smith et al. 2021).

Careful facilitation is required to create such environments, which include encouraging dialogue, interpreting cultural cues and feedback, diversifying delivery methods, catering for different learning styles and competence, allowing role models and mentors to lead, structuring small groups appropriately and providing experiential learning opportunities.

Conclusion

Adherence to the AIDR lessons management process has ensured these lessons are directly shaped by demonstrated, real-world experiences. People contributing to debriefing and the collection of observations were physically immersed in the undertaking of the activities and, thus, provided an experiential perspective rather than that of an observer. The CFP will use the learnings from this process in 2 primary ways:

- We will continue to embed learnings in our program delivery and in the establishment of partnerships and collaborations with First Nations people for mutual benefits.

- We will develop knowledge products, resources and trusted advice that provides guidance to other agencies on how to apply these learnings in their cultural burning programs.

For other outcomes, we hope that this will:

- increase the success of cross-cultural collaborations on cultural burning in Western Australia, with potential for broader application

- lead to greater empowerment for First Nations Australians to undertake more cultural burning on their Country.