Environmental hazards and climate change disproportionately affect Indigenous peoples and raises important concerns for social equity, environmental justice and disaster risk reduction. The under-representation of Indigenous peoples in natural hazard policymaking also impacts on the acceptability and relevance of disaster risk reduction initiatives to First Nations peoples. Indigenous concepts, values and understandings of environmental justice are pertinent to climate change mitigation, transformative practice and sustainable futures. This research was a collaboration between Māori academics and Māori community members and explores local understandings of Indigenous peoples of disaster risk reduction and highlights the need to maintain harmony and balance among humans and in relation to the natural world. Using a papakāinga [traditional village] framework and rongoā [healing systems], the study demonstrates how traditional Māori practices can address environmental challenges such as Per- and Poly Fluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) contamination, land degradation, biodiversity loss and increasing flood events. Findings of this study highlight the importance of Indigenous cultural strengths and holistic frameworks to achieve climate resilience and sustainable futures.

Introduction

Environmental hazards and climate change disproportionately affect Indigenous people, exacerbating existing vulnerabilities and raising significant concerns regarding social equity, environmental justice and disaster risk reduction. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC 2023), Indigenous communities face heightened disaster risks due to their dependence on natural resources, geographic exposure to climate-related events, and limited access to adaptive resources. Working with the Ngāti Raukawa Northern Marae Collective, Ngāwairiki – Ngāti Apa and Ngāti Hauiti ki Rātā from the lower North Island of Aotearoa New Zealand, this research centres the voices of kaumātua [elders] and whānau [families] while exploring how strengthened connections to whenua [land] can enhance mauri [energetic life force] and foster collective wellbeing. Framed by a papakāinga [traditional village] view, the research prioritises intergenerational collaboration to mitigate pressing environmental challenges which are the legacy of colonisation such as confiscation of territory, land degradation, biodiversity loss and flooding while addressing ongoing intergenerational trauma exacerbated by contemporary environmental and social issues.

Interrelating traditional knowledge with contemporary disaster risk reduction strategies enables this study to highlight the importance of maintaining harmony and balance between people and the natural world while sharing how Indigenous perspectives can shape equitable and effective responses to environmental crises. According to Professor Huhana Smith (Smith n.d). Māori knowledge systems such as kaupapa Māori and mātauranga Māori [Māori traditional ancestral knowledge] play critical roles in fostering sustainable environmental practices. Smith suggests that these systems emphasise interconnected relationships between people, land and ecosystems and reflect a deep ecological understanding. Projects formed by these frameworks prioritise the integration of Indigenous knowledge with modern scientific approaches and foster beneficial outcomes for iwi [tribes] and hapū [subtribes] while addressing contemporary environmental challenges. Smith highlights that research outcomes are designed to create shared benefits for all communities (Smith n.d.).

This paper tells the story of one of the Rangitīkei River hapū [family groups] within the Ngāti Raukawa Northern Marae Collective, that is dealing with PFAS contamination of their ancestral lands from the Royal New Zealand Air Force Base at Ohakēā. The hapū address these historical and contemporary challenges by using papakāinga [traditional village framework] and rongoā [Māori healing systems] to foster collective wellbeing, reduce disaster risk and pursue environmental justice.

Note on terminology: This article uses first person pronouns as the primary author is narrating from her experience as a hapū member within the research team.

Site history and PFAS contamination

Indigenous communities worldwide often face disproportionate environmental risks including effects of pollution (Fernández‐Llamazares et al. 2020) and climate change (Redvers et al. 2023). For Indigenous peoples in white, settler-colonial societies additional affects include land alienation or loss, marginalisation, discrimination, food insecurity, poor mental health and reduced resilience (Cormack et al. 2019; Moeke-Pickering et al. 2015; Moeweka Barns and McCreanor 2019). Living along the banks of the Rangitīkei River our hapū [descendants of a common ancestor] have endured intergenerational trauma (Pihama et al. 2014) since the confiscation of ancestral lands through pene raupatu [confiscation by way of the pen] in the 1800s (Richardson et al. 2024). This disconnection from the whenua has profoundly affected the community and the environment, leading to a decline in mauri [life force]. Recently, contamination of traditional homelands and waterways by PFAS chemicals has compounded environmental injustice, threatening health as well as cultural and spiritual wellbeing (Savage and Richardson 2021). These ongoing consequences reflect the challenges documented in the Waitangi Tribunal1 claims as Ngāti Parewahawaha, particularly for whānau at Mangamāhoe.

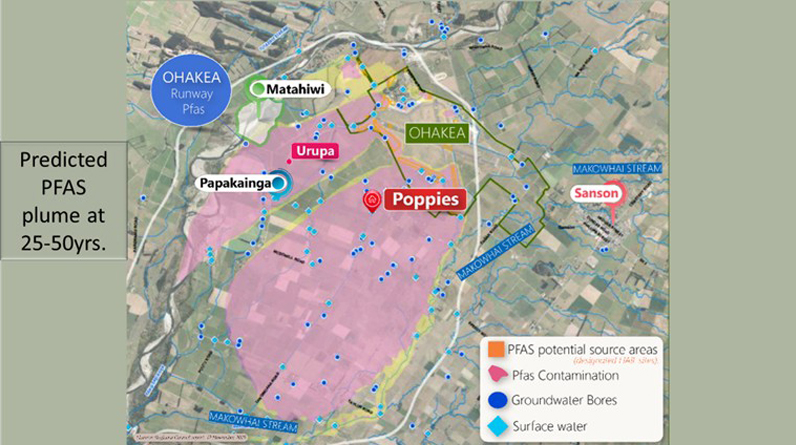

In Aotearoa New Zealand, PFAS, often referred to as ‘forever chemicals’ (Environmental Protection Authority 2023), have been widely used in firefighting foams, particularly at military bases. At the Royal New Zealand Air Force Base Ohakēā, PFAS-containing foams were discharged onto the runway between 1985 and 2005 as a regular part of fire suppression training and emergency operations. This led to environmental contamination. Investigations by the New Zealand Defence Force identified significant PFAS presence in the surrounding soil and water, including the Mākōwhai Stream. The spread of PFAS from the Air Force Base at Ohakēā (see Figure 1) has created a long-term environmental disaster for Indigenous lands to the south. The proximity of the Mangamāhoe eastern boundary to the Air Force Base at Ohakēā has placed our whenua [land] directly in the path of PFAS contamination flow, a chemical that does not break down in water and persists in the environment for generations to come. PFAS is gradually contaminating ground water at a rate of 50-100 metres per year. The plume is expected to expand to approximately 4,300 hectares over the next 50 years, with contamination lasting up to 150 years (Pattle Delamore Ltd 2019). Given the high water table in this area, any flooding worsens the effects, as PFAS is carried into the soil and deposited permanently. Over time, the compound will inevitably spread to the river mouth and surrounding beaches as it is carried in water. Indigenous communities reliant on these lands and waters face inter-generational challenges as the chemical compromises drinking water bores and contaminates the land used for agriculture and customary use. The risk of buying out the remaining ancestral land by the New Zealand Defence Force, as an imposed solution to the contamination, threatens our identity and traditional practices that are tied to the land and waterways.

PFAS contamination has had severe consequences for our community. We can no longer grow kai [food] on our land or drink from groundwater sources, which effects our health, traditional practices and resilience. The Mākōwhai Stream has been contaminated, making it impossible to gather kai. All biota living in the streams and edible vegetation traditionally harvested are now contaminated, rendering traditional food sources unsafe and environmental and health effects are expected to persist (Ministry for the Environment n.d.). The long-lasting PFAS compounds pose serious threats to the environment, traditional landowners and the health of the surrounding communities. Local farmers are aware that PFAS-contaminated concrete from an old runway surface was dumped along the banks of the Rangitīkei River and on Māori reserve land. This act polluted the already neglected riparian river margins, intensifying risk of extending contamination to the land, water and remaining ecosystems.

Soil testing confirms contamination of the waterways and land (Pennington 2024) and raises concerns for our health, environment and ability to sustain traditional practices. Chemical spread and rising levels of pollutant (Pennington 2024) threaten our connection to the land that affects our physical environment and our cultural identity. Despite precautionary measures from health officials (such as distributing bottled water between 2018 and 2022 until a NZD$12 million piped-water scheme was opened (Pennington 2014)), the long-term health effects have been played down and remain largely unknown. Farm owners as well as local and regional councils are tasked with monitoring the slow-spread contamination. However, full cleanup and recovery could take generations, thus is the magnitude of the environmental injustice faced by our community. PFAS contamination of the land and waterways has impeded customary practices associated with kaitiakitanga [guardianship] and so we are looking towards traditional innovation to address this.

Figure 1: Overlay of whenua including Papakāinga housing, Poppies homestead, the urupā [cemetery] in the plume. The blue circle outside of the plume shows the location of the old runway spoil/Māori reserve land, riparian margin restoration and whānau farm.

Source: Adapted from RNZAF Base Ohakea Investigation: Comprehensive Site Investigation Report (Pattle Delomore Ltd., 2019).

Research design

Kaupapa Māori framework

This study used kaupapa Māori methodologies, prioritising Māori knowledge, tikanga Māori [customary practices] and cultural values (Smith 2012). Kaupapa Māori challenges inequities and seeks transformation through Indigenous-led approaches to research. Using a kaupapa Māori framework, this research adopted a papakāinga [traditional village] lens and is grounded in qualitative methodologies. According to Pihama (2001), kaupapa Māori research prioritises addressing injustices, uncovering inequities and driving transformative change. With whānau at the centre of this inquiry, Winiata (2002) emphasised the importance of researching people at home, by people from home, where ‘home’ typically refers to the marae or papakāinga. This approach ensures that the voices of whānau are faithfully represented and remain true to their origins. Since whānau are often cautious of external researchers, they may withhold important information or provide inaccurate details to protect sensitive kōrero [oral information] unique to their community. Thus, careful handling is critical to maintain the credibility of the kōrero to ensure that Indigenous knowledge is accurately reflected by researchers who are either trusted whānau members of and/or known to the community.

Methods

This research was a collaboration between Māori academics and hapū along the Rangitīkei River in Aotearoa New Zealand. It engaged mātauranga Māori [Māori traditional ancestral knowledge] and local intelligence to develop culturally grounded disaster risk reduction initiatives for hapū along the banks of the Rangitīkei River from the headwaters to the sea in the central North Island of Aotearoa New Zealand. Findings presented draw on several research projects that have been carried out over the last decade, including a report developed by the Ngāti Parewahawaha hapū for our Waitangi Tribunal claim, which is currently in the process of being heard by the Crown.

The research involved:

- qualitative interviews: semi-structured discussions with knowledge holders

- wānanga [gatherings]: collaborative workshops to share knowledge and develop disaster preparedness plans

- focus groups: facilitated discussions about community-led approaches to resilience and recovery

- document review: review of mātauranga from the early 1800s within traditional sources such as whānau manuscripts and recorded and written kōrero [talk].

Participants and recruitment

The trustees of the marae committee sought support to gather evidence on behalf of whānau affected by river flooding and chemical contamination originating from the adjacent Ohakēā Air Force Base. They also emphasised the need to develop disaster preparedness plans to address the ongoing effects of flooding and to improve community resilience. This process helped the development of disaster preparedness plans based on traditional knowledge, collaboration and shared experiences. Participants included whānau, marae trustees, kaumātua [elders] and rangatahi [youth] from hapū along the Rangitīkei River. Recruitment prioritised local connections with participants invited by marae [gathering place for descendants of an ancestor] committees and iwi leaders to ensure culturally appropriate engagement.

Interviews and hui

The research team attended the monthly marae meeting to listen to whānau concerns about disaster unpreparedness, particularly regarding flood and contamination risks. This hui, with 20 whānau in attendance, introduced plans to hold a series of wānanga aimed at sharing traditional knowledge, building resilience and creating response strategies. Twelve whānau of the papakāinga development were interviewed and 50 hui participants (confident in their shared kinship) shared narratives about environmental challenges and traditional knowledge. These discussions aimed to support the development of hapū-based resilience plans and foster community capabilities.

While formal research was used to document mātauranga Māori related to disaster risk reduction and hapū resilience, sharing of knowledge through wānanga prompted hapū members to implement programmes to address concerns identified. Actions included establishing a papakāinga, replanting native bush, growing traditional kai off site, reconnecting to the land, learning how to identify and use native plants, teaching traditional cooking methods and sharing rongoā [traditional Māori healing systems such as plant medicine] with disaster-affected communities (Richardson 2024). Richardson et al. (2024) focused on sharing traditional medicine with communities affected by Cyclone Gabrielle.

Research limitations

This study faced some limitations including restricted information, time and resource constraints. While the use of a whānau researcher fostered trust and encouraged whānau to share sensitive kōrero, it is acknowledged that certain mātauranga Māori are protected and cannot be shared. The research was delayed due to COVID-19 pandemic restrictions and difficulties experienced booking marae post-pandemic due to demand for the facility. Limited funding and capacity restricted the ability to fully immerse within the papakāinga [traditional village], which would have provided a clearer understanding of the interwoven dynamics of whānau life, cultural practices and the lived experiences of environmental challenges. For some participants, competing demands on their time may have prevented them from attending or fully participating in collective wānanga activities. Despite these limitations, the research offers important insights while highlighting the need for sustained investment and flexible approaches to Indigenous-led research.

Papakāinga as an analytical template

Papakāinga has been used as a Māori housing tool kit (Rotorua Lakes District Council 2020) as a research topic (Menzies 2023; also see Cram et al. 2020) and as a case study in the development of quantitative kaupapa Māori methodology (Henry and Crothers 2019). However, we are unaware of scholarship that has used papakāinga as a template for organising and interpreting research material. The papakāinga template was developed by the first author and her whānau as the main analytical tool for this research. The template integrates mastery in emotional, cultural, spiritual, physical, environmental knowledge aligning with Māori worldviews and promoting collective wellbeing. Papakāinga [traditional village] highlights kinship, collective living and traditional knowledge systems to restore harmony between people and the environment. As a model for resilience, papakāinga enables whānau to strengthen ties to whenua, recover mauri and foster sustainable futures through Indigenous environment stewardship. The template incorporates the following Kaupapa [principles]:

- Mātauranga: traditional knowledge systems

- Te Taiao: the natural world, whenua and relationships between people and the environment

- Wairuatanga: spirituality, mauri, as well as the cosmological and cosmogonical features that are the basis for Indigenous identity

- Rongoā: traditional healing systems to support holistic wellbeing, balance and harmony

- Whakapapa: genealogy, identity, leadership, customary rights, institutional knowledge

- Kaitiakitanga: sustainability, protection, restoration and stewardship of the natural environment and its relationship to wellbeing

- Whānau: kinship ties, intergenerational support, kāinga, collective living and wellbeing

- Rangatiratanga: self-determination and control over one’s destiny.

Acknowledging centuries of conversations and manuscripts, these themes emerged organically as key elements reflecting traditional knowledge systems and holistic wellbeing. The principles became the agreed overarching template – comprising Mātauranga, Te Taiao, Wairuatanga, Rongoā, Whakapapa, Kaitiakitanga, Whānau and Rangatiratanga – through which all interviews and research materials were analysed. Using a papakāinga lens (a model of collective living on ancestral lands) as a case study, we aimed to identify new possibilities for healing and recovery within the community. At the conclusion of the research, whānau reflected on their participation, sharing insights gained and emphasising the need for this research and the significance of the outcomes identified by kaumātua [elders].

Human ethics approval for the research was obtained from Massey University, approval number OM3 24/01.

Findings

This research shows the transformative potential of interweaving Indigenous knowledge systems into disaster risk reduction and environmental justice initiatives. Indigenous knowledges and practices, such as local environmental indicators for disaster preparedness, can complement modern climate adaptation strategies. The papakāinga framework illustrates how traditional living systems can inform climate-resilient housing, land management and community planning. This section considers papakāinga and rongoā Māori as hapū resilience and disaster preparedness tools.

Papakāinga and collective wellbeing

The papakāinga framework emerged as a cornerstone to foster collective wellbeing and environmental stewardship within the research. Te Puni Kōkiri (2024) highlighted that papakāinga developments incorporate shared spaces and communal facilities such as gardens and orchards, which promote sustainable living and enhance cultural and spiritual connections. The papakāinga incorporates features that enable Māori communities to adapt, strengthen kinship ties and enhance whānau resilience through collective living. Papakāinga revitalises cultural practices such as karakia [rituals], rongoā [healing systems] and maara kai [village gardens], which support holistic health and environmental sustainability. The papakāinga framework serves as a model for sustainable development that balances human needs with environmental care.

Papakāinga embodies collective living, inter-generational support, a whakapapa [ancestral] connection to whenua [land, waterways, mountains] and a spiritual acknowledgment of overall wellbeing. By revisiting this traditional way of life, we can explore its relevance for whānau wellbeing, modern resilience planning, community health and environmental restoration.

Initial findings suggest that papakāinga strengthens kinship ties and fosters a reconnection with traditional knowledge systems crucial to address emerging environmental challenges. These ancient Māori knowledge systems offer transformative pathways to restore balance and harmony between people and the environment aligning with broader Indigenous understandings of environmental justice. Despite the potential for healing through papakāinga, our whānau continue to confront activities that degrade lands and waterways. Ongoing exposure to environmental hazard disproportionately affects local Indigenous communities (Fernández‐Llamazaresm et al. 2020). This highlights the urgent need for inclusive and culturally relevant sustainable initiatives that recognise and integrate Indigenous concepts of environmental stewardship and justice.

Since the early 1800s, Ngāti Parewahawaha has resided in papakāinga along the Rangitīkei River where our marae was constructed in 1967. The traditional environment of papakāinga considers kaupapa tuku iho [values handed down by tupuna Māori] that underpin our ways of living, interpreting the world and analysing the teachings passed down through generations. Papakāinga illustrate the value of living as a whānau, highlighting hapū and local intelligence, shared hapū mātauranga [local knowledge], tikanga [customs] and kawa [protocols] and, importantly, the capacity for our whānau and mokopuna [generations to come] to build on the vision of sustainability through kaitiakitanga [guardianship].

A new whānau papakāinga at Mangamāhoe opened in January 2025 on the whenua of Ngāti Parewahawaha in accordance with the traditional notion of whānau working and living together in harmony. Rebuilding the papakāinga, restoring the surrounding native flora and addressing PFAS contamination are ways that our hapū are managing the ongoing risk of land confiscation. The stories of whānau have identified how our mātauranga [knowledge] to support papakāinga development mimics traditional notions of living, promotes safe housing for whānau and connects to whānau resilience.

Integration of Rongo ā Papakāinga framework

Research emphasises the holistic health benefits of using Indigenous frameworks, particularly within Māori communities (Reweti 2023; Wilson et al. 2021). Rongoā Māori, a traditional healing system, encompasses spiritual, emotional and physical wellbeing and effectively counters the adverse effects of environmental degradation. Ahuriri-Driscoll et al. (2022) highlighted that rongoā Māori connection with the land is integral to identity and wellbeing and emphasised the reciprocal healing relationship between people and environment. Further, restoring natural ecosystems, such as wetlands and native bush, contributes to environmental health and emotional healing for whānau.

Rongo ā wairua [spiritual wellbeing]

Traditional rituals such as karakia [mediation and prayer] and whakawaatea [clearing] connected participants with atua and celestial beings and reinforced a sense of purpose and balance in responding to environmental challenges (Richardson et al. 2024). At the heart of papakāinga life, karakia is practiced morning and night by specific knowledge holders to acknowledge atua, seek guidance and protect the wellbeing of the whānau. Karakia unites whānau and provides spiritual grounding and connection to foster a collective sense of purpose. When opening the papakāinga in January 2025, a traditional ritual was conducted to protect and reset the mauri [energy] of the site as explained by a hapū member, ‘Whakatō mauri [setting energy to a place] was done at the papakāinga to ensure those that live their flourish’ (PS 2024).

Māori spirituality is linked to the environment with loss of mauri ora [balance] linked to unhealthy whenua [land] and languishing native ecosystems (Harmsworth and Awatere 2013). Knowledge of traditional rituals to restore noa [ordinariness] such as karakia [mediation and prayer] and whakawaatea are essential in disaster contexts. For example, following the devastating 6.1 magnitude Christchurch earthquake on 22 February 2011 that killed 185 people and injured thousands, both local and international first responders and Urban Search and Rescue Teams accessed local Ngāi Tahu kaumātua for whakawaatea and to debrief (Phibbs et al. 2015). In this way, rongo a wairua supports mental and physical wellbeing in times of stress as well as in post-disaster contexts.

Rongo ā tinana (physical wellbeing)

The physical health of whānau is closely tied to access to clean water and safe food sources. PFAS contamination has compromised these essentials, highlighting the urgent need for systemic change and restoration of Indigenous food systems based on local environmental knowledge. For example, a hapū member described the importance of traditional mātauranga Māori for planting and disaster planning:

As a whānau we hold hui (workshops) to pass on and practice our mātauranga Māori (traditional ways). By reading the tīkōuka tree in November we can determine whether the season ahead will be wet or dry. This knowledge allows us to prepare for what is coming between December and March, ensuring resilience and readiness for environmental changes.

(PR 2023)

The communal nature of papakāinga enables coordinated planning and mutual support during events such as flooding and drought. Whānau can collectively stock emergency supplies, create evacuation plans and implement sustainable infrastructure such as raised gardens or permeable pathways to reduce flood risks. Maara kai [village garden] initiatives reintroduce sustainable gardening practices rooted in ancestral knowledge as explained by a hapū member:

My great-great grandfathers’ role was to protect the south side of the Rangitīkei Rriver and he was also a provider of kai (food) through a huge maara kai (village garden) which we were told ran a few kilometres along the riverbank and on the current site of Ohakēā Airforce Base. Many traditions were passed down to my father as he too was an avid village gardener, farmer…

(RR 2024)

Restoring customary gardening traditions and growing traditional foods promotes rangatiratanga [self-determination] while ensuring that the inter-generational transfer of knowledge and local food insecurity are addressed.

Rongo ā hinengaro (emotional wellbeing)

Disconnection from the whenua has profoundly affected our community and the environment, which has led to a decline in mental and emotional wellbeing. The communal support system inherent in papakāinga plays a vital role in positive mental health. It provides access to rongoā [traditional healing] passed down through the generations and creates spaces to kōrero [share], reflect and learn, which supports whānau to navigate challenges together. Research indicates that positive mental and emotional wellbeing buffers negative post-disaster psycho-social effects. Receiving and offering help promotes recovery and resilience for individuals and communities through supportive social networks and collective problem solving (Resilience Challenge n.d.).

Rongoā Māori, as a holistic and cultural healing practice, incorporates deep, personal connections with the natural environment. For centuries, whānau Māori have cultivated rongoā, passing its unique knowledge down through generations. The practice is derived from mātaturanga, which many Māori regard as central to their identity (Te Whatu Ora n.d). By embracing rongoā and strengthening communal bonds such as papakāinga, whānau can enhance their mental and emotional wellbeing, particularly in times of adversity, such as contemporary housing insecurity, as explained by a hapū member:

Our papakāinga is also a refuge for those hapū members requiring a retreat or homeless who work on the farm in return for lodgings. Recollections of kaumātua and kuia who would have their own cabins on the papakāinga showed the multi-generations residing there. Living together provided the support that all whānau could benefit from.

(MT 2024)

Rongo ā whānau (family and relationship wellbeing)

Whānau narratives emphasise the deep connection between whakapapa [genealogy] and the expression of rongoā [traditional healing practices] in papakāinga. This interconnectedness strengthens kinship ties through collective knowing and being. Living in a papakāinga provides a foundation where whanaungatanga [relationships] and intergenerational living create opportunities for caring to ensure all whānau members are supported holistically and to collectively practice rongoā. This maintains traditional healing spaces and the ability to pass on matauranga [knowledge] for future generations. A hapū member said:

Our papakāinga is a place where whakapapa (connection) and rongoā (traditional healing) come together. We are connecting to atua (celestial beings), tupuna (ancestors), who did the same, and ensuring our mokopuna (grandchildren) grow up knowing their role in protecting the land and caring for each other for the wellbeing of current and future generations.

(KS 2023)

The papakāinga hosts many wānanga [educational gatherings] where kaumātua [elders] share the whakapapa of protocols and plants used in healing. Whānau learn to see themselves as part of an interconnected system of wellbeing, care and restoration to strengthen both spiritual and physical wellbeing.

Rongo ā wānanga (ancestral knowledge - space to be)

Wānanga [collaborative learning spaces] are essential to foster intergenerational knowledge exchange and create shared strategies for resilience within papakāinga. Regular monthly gatherings at the marae guided the design of wānanga, creating opportunities for iterative learning and collaboration. Wānanga [gatherings] were held at the papakāinga and along the Rangitīkei River to consider environmental challenges such as flooding and land and water contamination. These gatherings helped to explore whakapapa, share ancestral memories, develop disaster preparedness plans and solutions to address flood risks that are grounded in mātauranga Māori and contemporary science. By connecting whānau to tradition and each other, wānanga enhances cultural identity collective wellbeing and resilience as explained by a hapū member:

Tamariki [children] and mokopuna [grandchildren] are central to the transmission of knowledge on the whenua where they live. Including them in wānanga is essential to ensuring the oral transmission of matauranga, as this knowledge is both for them and about them. Their presence at places and spaces of historical significance strengthens their connection to their heritage, ensuring they receive and carry forward the stories and traditions of their whānau.

(PR 2019)

Rongo ā whenua (environmental wellbeing)

Rongo ā whenua embodies the reciprocal relationship between people and the land, emphasising care, respect and restoration. Grounded in kaitiakitanga, it acknowledges that the land sustains the physical, spiritual and cultural wellbeing of whānau. Spinks (2018) documented a 6-year hapū-led project at Lake Waiorongomai and demonstrated that ecological restoration grounded in Māori cultural values leads to transformative change and enhanced the mauri [life force] of both the environment and the community. Practices like maara kai [village gardens] and the protection of waterways are integral to this relationship to help future generations thrive in harmony with the whenua. A hapū member reflected on the effects of land alienation as well as ongoing environmental degradation over her lifetime:

Our papakāinga [homelands] is south of the Ohakēā Airforce Base. There is only one stand of rongoā rākau [native trees] left on our reserve that we now have to protect. All around us is intensive dairy farming. Prior to the settler’s arrival in 1840, our papakāinga was lush with ngahere (native bush), wetlands, birds, animals, insects, and freshwater kai [foods] feeding our emotional and spiritual wellbeing. In my lifetime, I recall the wetlands, but we don’t have any now, so all the animals, birds and Rongoā [traditional herbs] have gone. The presence of the airforce base further restricts the growth of trees as concerns over bird strikes on aircraft remain a priority.

(RR 2023)

Within this papakāinga, whānau have faced significant environmental challenges, including land alienation, contamination of the river from industrial activity and flooding caused by the destruction of native bush and wetlands that traditionally slowed the river. To address these issues, whānau adopted ongoing wānanga to develop ways to mitigate risk both now and into the future. Initiatives are in place to reduce flooding through restoring the ngahere [forest] and wetland ecosystems that are opportunities for healing and reconnection to all that once was. Whānau also actively engage in riverbank restoration, planting harakeke and tīkōuka to stabilise the soil and to filter pollution while reviving habitats for native wildlife. These actions are in line with traditional Māori understandings about the relationship between humans and the environment as explained by one hapū member:

My father shared when we care for the papatuānuku [land], she cares for us. Protecting the whenua (land) and water isn’t just an obligation; it’s a privilege and a legacy we pass on to our mokopuna.

(RR 2024)

Disaster preparedness for whānau and hapū involves traditional environmental knowledge and modern disaster risk reduction strategies to mitigate and respond to flooding and contamination. Wānanga shared narratives of early flood warning indicators, like being informed by whānau up-river, which allows 12 hours for the lower reaches to move stock and prepare. Modern tools such as flood mapping are combined with these insights to create a disaster plan that integrates with tradition. Rongoā Māori is often narrowly viewed as involving plants and trees. However, the atua Rongo embodies ease and peace across all facets of our environment. PFAS contamination which renders lands and waterways unsafe and raises important issues related to Indigenous environmental justice.

Environmental justice and restoration

Environmental hazard and climate change effects are patterned along lines of social inequality, with Indigenous peoples more likely to be affected, which raises important environmental and social justice concerns (Phibbs and Kenney 2022; Phibbs et al. 2024). The under-representation of Indigenous people in disaster risk reduction and environmental justice policymaking also impacts on the acceptability and relevance of sustainability initiatives to First Nations peoples. Indigenous concepts, values and understandings of environmental justice are pertinent to disaster risk reduction, climate change mitigation, transformative practice and sustainable futures (Phibbs and Kenney 2022). In white settler colonial societies, such as Aotearoa New Zealand and Australia, colonisation is a form of ecological violence that degrades Indigenous cultural integrity, health, food security, social resilience and environmental stewardship (Whyte 2018). The PFAS contamination of local whenua has rendered water use, the collection of kai [food] and traditionally harvested edible vegetation unsafe. In this case, the establishment of settler collective continuance through land confiscation, conversion for military purposes and subsequent environmental degradation has occurred at the expense of Indigenous cultural continuance (Whyte 2018).

Local indigenous understandings of environmental justice emphasise the need to maintain harmony and balance among humans and in relation to the natural world (Mihaere et al. 2024; Whyte 2018). A global review by Reyes-Garcia et al. (2019) highlighted that Indigenous peoples and local communities contribute significantly to restoring diverse ecosystems through leveraging traditional knowledge to enhance biodiversity and support ecosystem services. Papakāinga initiatives relocate Māori on ancestral lands, enabling local restoration efforts to effectively address both historical and contemporary environmental challenges. Hapū-led initiatives identified in this research include reintroduction of native vegetation as well as riparian and wetland restoration to mitigate the effects of PFAS contamination and flooding. The Māori concept of kaitiakitanga [guardianship] highlights the reciprocal relationship between people and the environment and focuses on long-term sustainability.

The weaving of Indigenous knowledge and Western emergency management approaches strengthens disaster preparedness and fosters community resilience. For example, Kenny et al. (2023) identified that integrating these epistemic approaches results in efficient and sustainable disaster risk reduction outcomes. Māori academics have highlighted the importance of customary environmental indicators and community-led initiatives in this context. Indigenous communities worldwide often face disproportionate environmental risks. The findings of this research reaffirm that Indigenous-led approaches, grounded in traditional knowledge and practices, are essential to build equitable and sustainable futures. By prioritising cultural strengths and holistic frameworks, communities can effectively address environmental crises while honouring their cultural heritage.

Conclusion

This study highlighted the transformative potential of Indigenous knowledge systems as embodied in the papakāinga framework to address contemporary environmental challenges. By reviving and adapting traditional Māori practices, this study illustrated how communities can reconnect with their whenua, restore mauri and enhance collective wellbeing. The findings advocate for the inclusion of Indigenous voices and methodologies in policymaking to create culturally relevant and sustainable disaster preparedness plans. As the whānau at Mangamāhoe prepared to inaugurate their new papakāinga in 2025, this research reaffirmed the value of Indigenous-led initiatives to confront environmental injustice, rebuild connections to the land and safeguard the wellbeing of current and future generations. Highlighting the role of papakāinga and rongoā in facilitating community resilience may have relevance for other Indigenous and marginalised groups advocating for equitable solutions to contamination and climate affects.