Previous disasters in Aotearoa New Zealand, including Cyclone Gabrielle in 2023, have highlighted that Māori have carried out effective and rapid responses during events by providing equipment, resources and support for all people in their local area.

Responses from iwi [tribes], hapū [extended family], whānau [family] and marae [communal gathering spaces] were seen to be highly effective compared with other agencies that were much slower to act during Cyclone Gabrielle. The importance of marae [communal place] during the response and recovery from disasters has been well illustrated following many disasters over the last 2 decades in Aotearoa. However, the wider emergency management system has frequently struggled to fully understand how to support, assist and respect marae operations and opportunities.

Since 2022, we have been working with local marae in Te Whanganui-a-Tara, Aotearoa New Zealand to identify the roles and responsibilities that they may perform in response to and recovery from emergencies to provide better outcomes for whānau, hapū and communities. Marae and Māori entities have the unique capacity and capability to serve communities with on-the-ground manaakitanga [paying respect] in times of response. Marae and Māori entities are spread across the country. Marae can provide food, water and accommodation for large numbers of people and can mobilise kai mahi [volunteer workers] quickly. The evolving Coordinated Incident Management Systems (CIMs) arrangements in Aotearoa New Zealand propose to introduce a new iwi liaison function titled ‘tākaihere’, which means to wrap around.

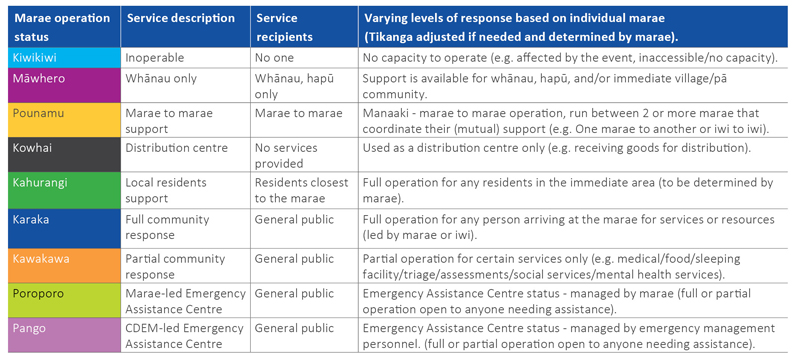

The tākaihere function will liaise with iwi and hapū during a response event. How marae whānau choose to work and connect with the tāikaihere function in the local Emergency Operations Centre is entirely up to them. Each marae can fluidly operate and move their response levels within any of the levels of operation status as indicated by different colours in Table 1.

Marae operating framework

A marae operating framework is presented here that can inform tikanga [static] and kawa [flexible] processes that are applied at each marae. Having this framework, along with the different levels and types of service that might be needed (considered pre-event, but flexible post-event and shared widely and transparently) enables all partners to work together effectively. This minimises cultural safety risks and operational pressure.

The framework’s structure was developed from matauranga [knowledge] of Te Ao Māori, tikanga, kawa and marae practices by the Senior Māori Advisor [the author of this paper]. The framework was discussed as a draft in collaboration with emergency managers to determine how New Zealand Ministry of Civil Defence and Emergency Management (CDEM) might support marae who exercise rangatiratanga [self-determination] during disruptive events to manaaki whānau [support families] and the wider community.

Figure 1. Takapūwāhia Marae community emergency training.

Image: Professor David Johnston

Table 1 provides a summary (at a glance) of service levels and support needed for each marae. It shows how marae might support other marae with their own response. It is anticipated that CDEM and marae could respond to an emergency better with this basic resource. The table illustrates how marae can determine their operation status and flexibly move between, and up or down, as capacity changes during a response. This table can assist planners when communities are moving from response to recovery phases after an emergency event. Training and exercising have been undertaken so people can understand how to apply the framework in a real emergency. Testing of the framework as represented in Table 1 during exercises has highlighted that it was well received and considered a good foundation resource that is simple to use and effective.

Table 1: Marae operation framework.

Māori emergency advisors can use this framework to expose marae to the options they have to quickly stand up their response teams and quicken the support they might require during activation from CDEM. This helps to minimise risks to communities. This framework can also determine how emergency managers who have access to resources can support marae to manaaki whānau, and possibly the wider community, in a disruptive event. This framework can inform what tikanga [static] and kawa [flexible] processes are applied at each marae. Consideration of this framework before an emergency or disaster strikes, and being flexible after the event, will help all parties to work together effectively and minimise cultural mistakes.