This study explored Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ experiences receiving Aboriginal cultural support from a public health unit in Hunter New England Local Health District in New South Wales. Using an Indigenist research approach, an online survey was conducted as well as yarning with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who had received cultural support while in isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Non-Aboriginal parents and carers of Aboriginal children were also eligible. Of 3,819 eligible individuals, 70 surveys were received with 55 valid responses after excluding 15. Using purposive sampling, 60 individuals were invited to participate in a yarn. Fifty-five participants completed the online survey and reported that the Aboriginal cultural support model they received was helpful and supportive. Yarns revealed valuable insights and lessons learnt for future pandemics. Three themes emerged: 1) cultural and community obligation, 2) culturally centred COVID-19 support and 3) accessing trusted COVID-19 information. This study highlighted the importance of Aboriginal-led pandemic responses. Embedding Aboriginal cultural support into public health responses enables tailored communication, strengthens relationships with Aboriginal communities and reinforces Aboriginal leadership.

Introduction

The World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a worldwide pandemic on 11 March 2020. Australia implemented national lockdown restrictions in March 2020. New South Wales (NSW) introduced a range of public health and social measures to help control the spread of COVID-19, including restrictions on indoor and outdoor movement, wearing masks, non-essential business closures, home isolation and quarantine, travel restrictions and mandatory hotel quarantine for overseas arrivals (Capon et al. 2021).

For many Aboriginal people, the use of punitive and controlling language in public health emergencies, such as ‘surveillance’ and ‘non-compliant’, can evoke painful memories of assimilation and segregation, reinforcing feelings of systemic oppression, control and historical trauma (Donohue and McDowall 2021). Research following the 2009 H1N1 pandemic revealed distrust and scepticism among Aboriginal people and communities because previous pandemic plans were developed without respectful engagement with communities (Massey et al. 2009). This research found that Aboriginal people wanted to work collaboratively with government and be included in the development of pandemic plans and responses that considered specific strategies tailored to Aboriginal peoples based on culturally grounded holistic models of care.

Aboriginal people and leaders were quick to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic at a national and local level. Many Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations (ACCHOs) and remote communities enforced their own measures and lockdowns to avoid the same effects of previous pandemics (Crooks et al. 2020). Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, Hunter New England Local Health District (HNELHD), Population Health had developed and embedded a cultural governance structure into its organisational decision-making to reflect the principles of co-design and two-way learning and sharing. This made it easier to replicate this structure in its COVID-19 Incident Command System (ICS) (Crooks et al. 2021; Crooks et al. 2023). This was done to include Aboriginal people in the prevention, preparedness, response and recovery phases of the COVID-19 public health pandemic response.

As the local COVID-19 response evolved, it was identified by Aboriginal staff members that there was a need to offer culturally responsive support for Aboriginal cases and contacts. In March 2020, the Public Health Aboriginal Team (PHAT), a team of Aboriginal staff from within HNELHD, was established to provide cultural governance in the local Public Health Unit ICS during the COVID-19 response. PHAT ensured that Aboriginal cases and contacts affected by isolation measures were offered holistic culturally appropriate and supportive care (Crooks et al. 2023). The team initially consisted of Aboriginal staff from the Public Health Unit, including a program manager, a registered nurse and an Aboriginal health worker and, as things progressed, the team grew to include clinical and non-clinical Aboriginal staff who were internal and external to HNELHD. PHAT understood that Aboriginal cases and contacts may feel more culturally safe and comfortable speaking to other Aboriginal people with similar lived experiences who could relate to the unique challenges arising from experiences with health services and government agencies. Support provided by the team included telephone calls, provision of food boxes, hygiene packs, health education and support, referrals to healthcare services, access to COVID-19 testing and vaccination as well as advocacy and referrals to other services and support agencies.

This study explored Aboriginal peoples’ experiences with receiving cultural support during the pandemic. The aim of the study was to develop better practices for how Aboriginal people can be supported in public health emergencies. This work was developed, led and conducted by HNELHD Public Health Aboriginal staff members.

Methods

The research team and standpoint

The research team consisted of members of the PHAT who were involved in the development and implementation of the Aboriginal cultural support model during the COVID-19 response in HNELHD. The team included public health practitioners and researchers with expertise in Aboriginal health, cultural governance, qualitative research, epidemiology and health protection. As Aboriginal researchers, we brought lived experience and professional expertise to the study, embedding Aboriginal perspectives to strengthen the integrity of the research.

Study design and setting

This study was conducted from March 2020 to January 2022. HNELHD is one of the largest health districts in NSW. It is approximately 160 km north of Sydney and extends north to the Queensland border and includes a mix of urban, regional, rural and remote communities (see Figure 1). HNELHD provides public health services to approximately 900,000 people, including 87,000 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who represent 25.9% of the total Aboriginal population in NSW (Centre for Epidemiology and Evidence 2024) (Figure 1).

Researchers conducted a mixed-methods study and applied an Indigenist research approach to explore Aboriginal peoples’ experiences in receiving cultural support during the pandemic. This approach aimed to understand what worked well, what did not work well and how Aboriginal people can be supported in future public health emergencies. Indigenist research centres Aboriginal communities and upholds the integrity as sovereign peoples (Kennedy et al. 2022). It means the entire research process is determined by Aboriginal peoples and is conducted in a culturally appropriate and responsive way that aligns with the cultural preferences, practices, struggles and aspirations of Aboriginal people. Yarning, as an Indigenous methodology, was used to gather data. Yarning enabled the collection of stories and insights by eliciting Indigenous worldviews and experiences (Kennedy et al. 2022).

Participants and recruitment

This study included individuals who received cultural support during the COVID-19 pandemic in the HNELHD during the study period. Participants were recruited for both an online survey and yarns. Invitations were sent via text message during April 2024. Individuals were given 60 days to accept and complete the survey. Interviews were conducted between May 2024 and November 2024.

Inclusion criteria

Primary participants were Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people aged 18 years and over who had received Aboriginal cultural support. Secondary participants were parents and carers of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children aged under 18 years old who received Aboriginal cultural support. This included non-Aboriginal parents and carers.

Figure 1: Map of NSW showing the health districts with Hunter New England Local Health District in yellow.

Source: NSW Health website www.health.nsw.gov.au/lhd/Pages/default.aspx

Exclusion criteria

Individuals were excluded from the study if they were hospitalised at the time of being a COVID-19 case or contact due to having access to support by Aboriginal Hospital Liaison Officers. People who had passed away since receiving cultural support were also excluded.

Online survey recruitment

Of 3,826 cases and contacts who received cultural support during the study period, 3,819 individuals were eligible and invited to participate in the online survey. Recruitment was conducted via a personalised text message using a mass messaging communications platform that included a link to the online consent form and survey. All parents and carers of children who were aged under 18 years at the time of receiving cultural support were able to complete the survey on their behalf. This included non-Aboriginal parents and carers of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children.

Yarning recruitment

Purposive sampling was used to select participants from the 3,819 eligible individuals to ensure diversity in age, gender and location across HNELHD. Sixty individuals were contacted via text message, invited to participate in yarns and provided with an information sheet and consent form. Survey participants who wanted to take part in a yarn were sent an invitation via MS Teams and an information sheet and consent form.

Data collection and analysis

Data were collected using quantitative and qualitative methods.

Online survey

We collected participant demographics, experiences with cultural support and feedback on the model for future pandemics. The survey consisted of 25 questions, most of which were measured by a 5-point Likert scale (1=strongly agree to 5=strongly disagree). Participants were given the opportunity to provide additional feedback or share their experiences in detail through free-text fields throughout the survey. Survey participants had the option to take part in a yarn.

Participants could complete the survey based on their own experiences or on behalf of a household or family member whom they cared for. Survey data was collected in RedCap and analysed using Microsoft Excel.

Yarns

Yarning was conducted to understand people’s experiences of receiving cultural support during the pandemic. We developed a yarning guide to ensure consistency across sessions while allowing participants to share their stories and experiences freely. The guide included prompts about their experiences, including what made it easier or harder during their isolation and strengths and challenges of the cultural support model.

All yarns were conducted by phone or Microsoft Teams and lasted between 30 and 60 minutes. Aboriginal researchers who were experienced in qualitative methods, conducted the interviews, with one asking questions and others scribing. With participant permission, yarns were recorded. Recordings were not transcribed to maintain authenticity of the yarning process (Bailey 2008; Kennedy et al. 2022). Participants received a store voucher of $20 for their time.

Three Aboriginal members of the research team conducted an inducted thematic analysis of the notes and recordings. The data was coded independently using an online collaborative whiteboard platform (Miro) and then discussed and reviewed to finalise agreed themes. This approach aligns with decolonising methodologies and Participatory Action Research principles, which prioritise Aboriginal worldviews. Qualitative data was analysed in a way that honours and reflects Aboriginal worldviews and respects Indigenous data sovereignty. Embedding Aboriginal perspectives and lived experiences into the thematic analysis ensured that both the process and findings were culturally relevant to Aboriginal communities. This approach enabled themes to emerge while maintaining the principles of Aboriginal knowledge and practice. The online platform tool facilitated real-time discussion and collaboration.

Ethics

This research was approved by the Hunter New England Human Research Ethics Committee of Hunter New England Local Health District, Reference 2022/ETH02532 and the NSW Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council Ethics Committee, Reference 2052/23. Informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Results

Online survey

Of the 3,826 cases and contacts who received cultural support, 7 individuals were excluded because they had passed away, leaving 3,819 eligible participants who were invited to complete the online survey. A total of 1,311 text messages were undelivered (480 messages were not delivered within the time window, 676 failed and 155 were rejected). Seventy responses were received; however, 15 responses were excluded for incomplete data or were deemed ineligible because they had not received cultural support. Fifty-five surveys were completed. The response rate for each question varied. This is possibly due to participants skipping questions that were not applicable to them or could be from survey fatigue or poor recall.

Most respondents who fully competed the survey identified as Aboriginal (n=54) and most were female (n=38). All respondents resided within the HNELHD with most in major cities (n=25), inner cities (n=20) and outer regional (n=7).

Among the respondents, 28 were COVID-19 cases, 8 were contacts of a COVID-19 case and 19 were initially a COVID-19 contact, but then became a COVID-19 case during their isolation. Most respondents were in isolation for 14 days (n=28) while some isolated for 10 days (n=6) or 7 days (n=18) and others (n=5) isolated for different durations.

The types of cultural support received by the participants varied. The most common type of cultural support was telephone support (n=43) followed by receiving food boxes (n=30) or hygiene items (n=21). Other support included help with accessing COVID-19 vaccinations (n=5), health advice and support (n=2) and supply of a mobile phone (n=1). Regarding frequency of phone calls, 38 respondents rated them ‘just right’ while 8 respondents felt the calls were ‘not enough’ and 2 felt they were ‘too much’. Seven respondents did not receive any phone calls.

COVID-19 information and advice

Most respondents (n=45) reported receiving enough information from the Cultural Support Team to safely isolate, with 44 out of 45 finding the information easy to understand. Of the 54 participants, 44 indicated the risks of leaving home isolation were clearly explained, while 11 stated they lacked enough information. One survey participant expressed their gratitude stating:

I am very grateful for all the information I received…I learnt from your team which provided me the knowledge to then have the conversations openly with my family members.

Respondents also sought information from other sources during their isolation. The Cultural Support Team was the key source of information (n=28) followed by NSW Health website (n=21), family (n=18), general practitioner (GP) (n=13), social media (n=13), Australian Government Health website (n=10), Aboriginal Medical Service (n=10) and friends (n=10).

Referrals to support services

Fourteen respondents reported being referred to other support services. Most were referred to mental health services (n=5) and COVID-19 home testing (n=5). Other referrals included supported health accommodation (n=1) and medical assessment (n=1).

Preferred sources of information for future pandemics

When asked about future communication during a pandemic, most respondents indicated Aboriginal Medical Services (n=38, 70.4%) as their preferred source followed by NSW Health (n=33, 61.1%) and Public Health (n=23, 42.6%). Other sources included National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (NACCHO) (n=21, 38.9%) and the Australian Department of Health (n=15, 27.8%). Two respondents suggested using mail drops and links with key organisations for future pandemic communication dissemination.

Overall views of cultural support

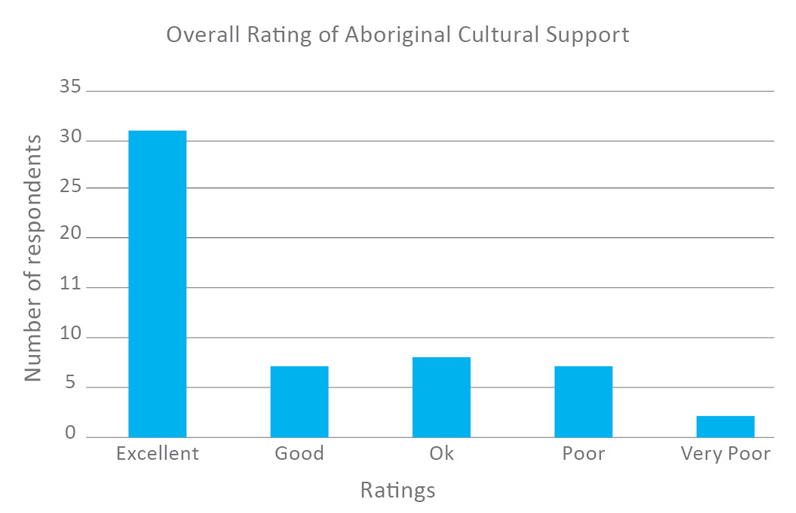

Most respondents (n=46) felt comfortable sharing their personal experiences of COVID-19 with the Aboriginal Cultural Support Team. Forty-one respondents indicated that the support was helpful and supportive and 5 did not comment. Most respondents rated the overall support they received as ‘excellent’ (n=31), ‘good’ (n=7) or ‘ok’ (n=8) (see Figure 2) with 81% stating they were ‘likely’ or ‘very likely’ to recommend cultural support to others. One participant appreciated the knowledge and support they received stating, ‘the support we received was helpful. the team were knowledgeable and friendly’. While another participant stated:

…without a calm, caring voice on the phone I believe my path of health could have gone a bad way. It was only because of their reassurance that I was taken via ambulance to hospital. They contributed to saving my life.

Many participants stated that cultural support is appropriate (n=54) and acceptable (n=55) during a pandemic. There was strong support for the continuation of cultural support and referrals in future pandemics (n=54) (see Table 1). Many respondents were supportive of receiving healthcare over the phone or video (n=43), while 9 were unsure and 3 strongly disagreed. Some appreciated the practical assistance, with one stating, ‘the food and hygiene products were a godsend also as our families were in lockdown also and we were not confident in asking for help from others’. However, another participant shared their frustration at not receiving a food box despite requesting one:

I believe it was a fault by our local services who on 2 occasions promised to drop one off but never did, which was a pity as we were all really sick and had to rely on friends and other family to drop off supplies, including, hygiene, food and medicinal supplies.

Table 1: Aboriginal cultural support survey responses about future pandemic responses.

| Statement | Total responses (n) | Variable | n (%) |

| The Aboriginal cultural support model should be planned, managed and led by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. | 54 | Strongly agree | 36 (66.7%) |

| Agree | 14 (25.9%) | ||

| Unsure | 2 (3.7%) | ||

| Disagree | 1 (1.8%) | ||

| Strongly disagree | 1 (1.8%) | ||

| Aboriginal cultural support should be provided by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. | 53 | Strongly agree | 30 (56.6%) |

| Agree | 14 (26.4%) | ||

| Unsure | 8 (15.1%) | ||

| Disagree | 1 (1.8%) | ||

| Strongly disagree | 0 (0%) | ||

| Aboriginal cultural support should be included in future pandemic responses. | 54 | Strongly agree | 43 (79.6%) |

| Agree | 11 (20.4%) | ||

| Unsure | 0 (0%) | ||

| Disagree | 0 (0%) | ||

| Strongly disagree | 0 (0%) | ||

| Aboriginal cultural support is an appropriate way to support Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people during a pandemic. | 54 | Strongly agree | 37 (68.5%) |

| Agree | 16 (29.6%) | ||

| Unsure | 1 (1.8%) | ||

| Disagree | 0 (0%) | ||

| Strongly disagree | 0 (0%) | ||

| It is acceptable for all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to be offered Aboriginal cultural support during a pandemic. | 55 | Strongly agree | 41 (74.5%) |

| Agree | 14 (25.5%) | ||

| Unsure | 0 (0%) | ||

| Disagree | 0 (0%) | ||

| Strongly disagree | 0 (0%) | ||

| It is acceptable for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to receive Aboriginal cultural support during a pandemic. | 54 | Strongly agree | 42 (77.8%) |

| Agree | 11 (20.4%) | ||

| Unsure | 1 (1.8%) | ||

| Disagree | 0 (0%) | ||

| Strongly disagree | 0 (0%) | ||

| It is acceptable for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to be offered referrals to support services during a pandemic. | 52 | Strongly agree | 43 (82.7%) |

| Agree | 8 (15.4%) | ||

| Unsure | 1 (1.9%) | ||

| Disagree | 0 (0%) | ||

| Strongly disagree | 0 (0%) | ||

| It is acceptable for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to receive referrals to support services during a pandemic. | 51 | Strongly agree | 40 (78.4%) |

| Agree | 10 (19.6%) | ||

| Unsure | 1 (1.9%) | ||

| Disagree | 0 (0%) | ||

| Strongly disagree | 0 (0%) | ||

| Now that we have been through the COVID-19 pandemic, it is more acceptable to receive other healthcare over the phone or video. | 54 | Strongly agree | 29 (53.7%) |

| Agree | 13 (24.1%) | ||

| Unsure | 9 (16.7%) | ||

| Disagree | 0 (0%) | ||

| Strongly disagree | 3 (5.5%) | ||

| It is acceptable to receive health information and advice during a pandemic. | 53 | Strongly agree | 40 (75.5%) |

| Agree | 12 (22.6%) | ||

| Unsure | 0 (0%) | ||

| Disagree | 0 (0%) | ||

| Strongly disagree | 0 (0%) |

Yarning interviews

A total of 9 yarns were conducted. Of these, 2 participants were recruited through purposive sampling, while 7 were sampling, while 7 were recruited through the online survey. Eight participants identified as Aboriginal and one was a non-Aboriginal carer of Aboriginal children. Yarns were conducted between May 2024 and November 2024 and ranged from 30 to 60 minutes.

Yarning provided a deeper understanding of participants’ lived experiences during the pandemic and framed 3 key themes that emerged, as well as actionable lessons to inform future pandemic responses.

Figure 2: Survey participants rating of Aboriginal cultural support received.

Strengths and challenges of personal COVID-19 experiences

Participants shared both enablers and challenges of their pandemic isolation. Strengths included adaptability, resourcefulness and a strong commitment to keeping their communities safe. In addition to the phone calls, practical support including access to COVID-19 testing, food boxes, information and advice and hygiene items was helpful.

Challenges included the inability to safely isolate, as well as the mental health effects of isolation. Participants described struggles accessing groceries and essentials as well as difficulties isolating safely, especially for large families living in small houses, with one participant sharing ‘having to sleep on the lounge with a mask’. Restrictions, not being able to go out, self-isolation and forced isolation had a negative effect on mental health. Additionally, grief and loss took an emotional toll for some participants. One participant shared they were: ‘unable to attend to Sorry Business at the same time which made it really hard’.

Participants shared personal stories of their past interactions and negative experiences with health services: ‘when you have a bad experience from health, that trauma will stay with you forever…you gotta have that trust and rapport, or you will not connect with me’. Some participants who felt very sick when they had COVID-19 refused to go to the hospital because of past experiences: ‘I didn’t go to hospital because of past negative experiences of being sent away’. This highlights the need for culturally responsive and supportive care and trusted Aboriginal health workers working in the health service.

Participants reflected on discriminatory legislation with the fear of government taking away children. This was a real and genuine concern, one said: ‘if I can’t feed my kids, I’ll have my kids removed. The Aboriginal Cultural Support Team were able to break down those barriers about [child protection services]’.

Despite the challenges, participants demonstrated strength, resilience and strong determination to do whatever was necessary to protect their family and community from getting sick.

Theme 1: Cultural and community obligation: keeping mob informed and safe

Participants expressed a strong sense of cultural responsibility and obligation to protect and support each other during the pandemic. They highlighted the importance of keeping everyone well-informed about COVID-19 risks and public health measures, especially those who needed the most protection. One participant reflected how well Aboriginal people were supported during the pandemic:

I realised we weren’t the only ones in our community that were struggling…[we were] sharing and liaising with other groups from all over the state…[and] sharing information that we were able to get from HNE (Cultural Support).

Participants felt a duty to share information provided by the Cultural Support Team to dispel myths, educate others and promote public health practices to keep families and communities safe. They felt an obligation to care for others by sharing knowledge and understanding of the pandemic through their local groups and networks. For example, one participant, a member of a local Aboriginal Men’s Group, shared the information gained from the Cultural Support Team with other men and men’s groups that were unaware of support services available to them, saying, ‘within our org (sic) we started online men’s groups. We were sharing information in these groups’. Participants stressed the importance of education through social and cultural networks and community groups to keep communities informed about pandemic risks because it’s ‘good to educate our community’.

Participants recognised the key role of Aboriginal health workers in breaking down complex pandemic information and sharing both population-wide statistics and local Aboriginal-focused data to identify gaps and prioritise local community support services and response. One participant who worked in community said:

…[when NSW Health stopped sharing the COVID-19 case numbers] I was checking the FluTracking numbers…mainly for my own benefit….but like when there’s big events on, or we are looking at planning things through work, I show my colleagues and sort of say here’s a spike, we need more hand gel at these events or just have masks on standby.

Participants appreciated receiving clear and relatable information and advice that empowered them to have discussions with their families about isolation and public health practices and were ‘able to educate family about support services available for them in other areas…[and] COVID-19 tests, drive through testing, masks, hand hygiene and washing everything’.

Theme 2: Culturally centred COVID-19 support: trust, connection and tailored care

Participants emphasised the need for culturally respectful, community-centred support. The Cultural Support Team’s holistic approach, grounded by an understanding of local cultural contexts, built trust and strengthened connections. Participants valued the tailored support, which was personal and relevant to their individual needs. Cultural support was offered in a variety of ways including phone calls, text messages and emails, food boxes, hygiene packs, medication and referrals to support services. One participant stated regular check-ins from the team were helpful: ‘having someone on the other end of the phone was better and safer’. One mother, whose child was extremely sick, shared the importance of the cultural support phone calls: ‘it’s good when you can talk to them and ask questions. Every question I asked they answered and if they couldn’t help, they gave me a number to call’.

Participants felt the cultural support phone calls were prompt and provided participants with reassurance and a sense of care: ‘they contacted me a couple of days later, a couple of follow-up phone calls and let me know they were there if I needed, I felt supported’. The frequency of phone calls varied and most participants felt it was appropriate and acceptable. One said: ‘we got a couple of calls. It was nice for them to just check in, cause no one else was checking in’. Another said the calls were ‘just right... 4 [calls] was plenty, any more would be too much’. The convenience of the calls was noted as a standout as one participant noted, ‘it was paperless – easy to communicate with, didn't have to tell your story to 50 different people. The information was consistent…and you knew what the phone call was about’.

While most participants found the information and advice accessible and helpful, one noted that literacy barriers affected their ability to fully engage with cultural support, ‘because of my lack of reading skills, I could have received more support in that aspect’. One participant noted that due to low literacy levels, they experienced difficulties home-schooling their children.

Many participants valued the high-level of support provided by the team, with one participant stating:

‘although I told the team I was fine, they still persistently made contact’ and another participant appreciated the ‘personalised phone call made me feel like I was listened to, validated’.

Participants reflected on the holistic support care the Cultural Support Team provided. One participant noted other communities did not receive ‘as much support as Aboriginal people in HNE’ and that ‘a lot of communities were doing it a lot worse than we were, because of the additional support HNE provided’.

There was a deep sense of appreciation and feeling valued, knowing that there was support available. Some said it was ‘unexpected and a surprise’ as well as reassuring to know that someone was caring for their wellbeing. It made people feel good and the education provided by the Cultural Support Team helped make things easier, as stated by one participant: ‘it was nice to know it was there, it made you feel secure, and made you feel good, and made me feel a bit special afterwards’.

The support helped individuals and families and empowered the wider community. One participant stated the team ‘was able to break down the barriers and give all different types of resources to help mob’.

Participants emphasised the Cultural Support Team’s inclusive and compassionate approach made them feel valued and respected, regardless of their position or status:

Basic human rights respect given from the Cultural Support Team to every single person – compassionate and understanding and explained, ‘I understand you don't need it, but we are going to send it to you anyway’…if there was something that I needed, I don't feel bad asking for it.

Another participant noted how the Cultural Support Team supported all individuals in a non-judgemental way stating: ‘[the team] didn't ask who it was for, you helped everyone and just gave it to mob’.

Participants indicated the care provided felt real and genuine, culturally grounded and community focused. This highlights the value of kinship and cultural understanding in fostering trust and providing essential assistance during challenging times. One participant said: ‘The cultural aspect is different, that connection in culture, feels…like a friend checking on me…having a yarn. Keep that there’. Another participant shared their experience of receiving regular phone calls:

…it was at a personal level, friendly, not prying, it was genuine concern for my wellbeing, and that person didn’t know me, but it was what she said it, how she said it, it wasn’t just a 2-minute phone call, we chatted for a while.

The care and support provided by the Cultural Support Team proved to be essential during the pandemic, with one participant stating:

…we would have been lost without you, the community would have been lost without you. I don’t think we would have survived because we didn’t get much help from other people.

Theme 3: Accessing trusted COVID-19 information

Participants highlighted the importance of access to trusted, reliable and culturally relevant COVID-19 information. Trusted sources such as Aboriginal health workers, Elders and community champions are essential to navigate complex and sometimes conflicting public health messages. Participants told us that the constant changing of information was confusing, overwhelming and confronting, which led to mistrust. Key sources of information included state and national government health websites, ACCHOs, pharmacists, Aboriginal media, social media and the Cultural Support Team. Many participants felt they trusted and valued the information from the Cultural Support Team. They trusted the information because they trusted the people. One participant stated:

…having connection with who was on the team. Knowing we were getting the right information we could trust and rely on’ and that ‘it’s a face that you know, and someone that you have that trust and faith in.

Participants said that young people felt scared about COVID-19 because of the unknowns and that reassurance from the Cultural Support Team lessened some fears. One said: ‘if [they] didn’t talk to [Cultural Support Team member] as much as they did, they wouldn’t have known how serious it was’.

The Cultural Support Team was acknowledged for providing clear, easy to understand, relevant and relatable advice with one participant stating:

…the information was easier to understand and was able to listen to because the team is known to the community, its different because you’re not likely to listen to those close to you.

The Cultural Support Team collaborated with the ACCHOs across the area and this was recognised as a strength. Participants noted how ‘localised messages that [ACCHO] did in conjunction with Aboriginal cultural support’ were designed and tailored to meet local community needs. Participants received information on topics including hygiene practices, staying away from each other to keep safe, COVID-19 testing and vaccinations, mental health tips, medication, signs and symptoms of declining health and when to seek care. One participant said: ‘the [Cultural Support Team] was able to provide more helpful information and showed us somebody cared. Good to have some information’.

Participants reflected that ‘the [public health] rules at the time didn’t make sense to the community around isolation’ and recommended that pandemic messages be simplified and that the Cultural Support Team could be the translators and deliverers of complex information:

…if they [cultural support] were passing on info…just the facts...[about] what you are allowed to do, not do, more basic so it’s easier to understand, it got very confusing in the end, you didn’t know what you were doing.

Lessons from COVID-19: strengthening future public health emergencies for Aboriginal communities

Participants identified successes and strengths of the cultural support model, including personalised and individual care and support, practical support such as food and hygiene boxes, access to information, regular phone calls and trusted team members who could communicate honestly and directly. One participant praised the Cultural Support Team’s efforts and the difference they made for Aboriginal communities in HNELHD: ‘if mainstream health took a lesson from the Cultural Support Team, you would see big differences’. They also noted the dedication and commitment of the team and importance of prioritising staff wellbeing: ‘at the end of the day our communities need our health workers are healthy’. They suggested improving future public health responses through the use of culturally appropriate community-led responses, strong communication and early engagement with Aboriginal organisations.

Key recommendations for future cultural support

Participants provided recommendations for cultural support:

- Additional efforts to support individuals with lower literacy levels by developing tailored resources and strategies that improve accessibility such as social media messages and videos to enhance online engagement.

- Enhanced promotion and communication through broader advertising and visibility of the Cultural Support Team and increased awareness of local support services.

- Improved accessibility by establishing a cultural support hotline or an online chat function for people to access after hours.

- Using technology systems and platforms to gather background information prior to a cultural support phone call. Communicating with individuals using video calls for more personable and supportive care. Sending text messages and links to online information.

- Partner with Aboriginal stakeholders including ACCHOs as well as local Aboriginal health workers to coordinate on-the-ground efforts in community.

- Partner with Aboriginal communities, for example connect and communicate with Aboriginal peoples in future pandemics using stronger communication messages ‘in a user-friendly way and plain language’ and through a variety of modes including social media platforms, videos and storybooks to attract children and young people. Participants noted the significance of Aboriginal events, gatherings and networks as important for information sharing.

- Improving government and health services systems and responses to support Aboriginal people in future pandemics. One participant stated they observed the hospital was not prepared nor equipped to deal with the influx of Aboriginal cases and the need for health services to be more aware of cultural contexts and needs of the local community, including:

- cultural respect and awareness training: non-Aboriginal health staff undertake cultural respect training to better understand and meet local community needs

- accommodation support: participants acknowledged that some families lived in crowded housing and could not afford to pay for accommodation to safely isolate and suggested Aboriginal peoples be supported with accommodation

- provision of personal protective equipment (PPE): ensuring adequate resourcing and distribution of PPE in Aboriginal communities

- collaboration with other services: all services, government and non-government, work together to plan and prepare for future pandemics to ensure local responses are ready to go.

Discussion

This study highlighted the importance of Aboriginal-led, culturally informed and tailored support for Aboriginal people when responding to public health emergencies. The depth of engagement with participants during the study meant the findings were grounded in lived experiences and provided valuable insights for future public health emergency policy and practice. Aboriginal people can face significant barriers to health care, which are exacerbated during pandemics. This highlights the need for flexible, accessible and responsive health services so that Aboriginal people are not further disadvantaged (Nolan-Isles et al. 2021) or targeted (Boon-Kuo et al. 2021). Participants reported that the Aboriginal cultural support model was acceptable, appropriate and effective, with high levels of satisfaction. Fundamental factors contributing to the model’s success included holistic care and support, trusted relationships with local Aboriginal health workers, development and dissemination of culturally appropriate and relatable communication. Participants valued being able to access clear and reliable information that helped them to keep their families safe during the pandemic. These findings point to the importance of embedding cultural support and Aboriginal representation in local pandemic responses.

Aboriginal people have been continuously overlooked or considered as an afterthought in public health responses and this is a shared experience endured globally by Indigenous peoples (Markwick et al. 2014). This time, HNELHD aimed to show that it is possible to change the narrative by working collectively to centre Aboriginal families and communities in the response. By prioritising Aboriginal voices and needs, HNELHD ensured that the pandemic response was not only inclusive but helpful and not harmful. The findings suggest that the cultural support model was successful for a few reasons. Firstly, it was developed and implemented by Aboriginal people. This aligns with the findings from the National COVID-19 Response Inquiry Report (Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet 2024) noting that it is crucial to have Aboriginal community-led responses. The report recommended that future public health responses need to be inclusive and better prepared to address the challenges of Aboriginal communities and ensuring those needs are prioritised in emergency management planning. Secondly, the team embedded support options and assistance for Aboriginal cases and contacts. Early engagement with Aboriginal communities and stakeholders helped Aboriginal peoples stay informed of changing information and there was activation of support to areas that needed it (Crooks et al. 2020). Lastly, engaging with Aboriginal stakeholders and organisations throughout the pandemic built trust and strengthened connections. This shows the importance of health systems incorporating cultural values, lived experiences and Aboriginal ways of knowing, being and doing.

Findings

Culturally appropriate and holistic support

Past pandemic plans and responses often overlooked the needs of Aboriginal people and communities, leading to ineffective disease control strategies (Massey et al. 2011). We applied the learnings from previous research, reinforcing the importance of Aboriginal-led and community-focused approaches. This aligns with other research that shows the effectiveness of addressing health inequities during a pandemic (Fredericks et al. 2024). Similarly, the Gurriny Yealamucka Health Service highlighted the importance of community-control and self-determination to enable strong governance and leadership capacity to respond to the pandemic (McCalman et al. 2021).

The Aboriginal cultural support model demonstrated the importance of culturally appropriate and tailored care in building trust between public health and Aboriginal communities. Participants highlighted the profound benefit of a culturally responsive and sensitive approach, which includes holistic support, such as food boxes, hygiene items and phone calls, to address past injustices and sociocultural determinants of health (Stanley et al. 2021).

Communication and trust

Effective communication is crucial for everyone during a pandemic, especially for Aboriginal communities, and must be culturally appropriate to foster understanding, trust and action of public health measures. Participants in this study emphasised the value of receiving clear, relatable and culturally appropriate information from local, known and trusted sources who offer practical guidance are essential for keeping communities safe (Massey et al. 2011). This aligns with other studies showing that trusted messengers of information, such as Aboriginal health workers and community leaders, are crucial in addressing misinformation and communicating public health advice that makes sense for Aboriginal peoples (Finlay and Wenitong 2020; Seale et al. 2020; Walter and Andersen 2013).

Attending cultural and social gatherings, such as funerals and community events, is important for Aboriginal people even when they may be unwell (Massey et al. 2009). Disseminating public health information through significant cultural events and gatherings was suggested to inform community members about pandemics and the associated risks. Tailored and culturally relevant and relatable information can help reduce public health risk to Aboriginal communities (Seale et al. 2020). Participants preferred to receive public health communications primarily through ACCHOs due to their established and trusted relationships with Aboriginal communities (Finlay and Wenitong 2020). This emphasises the importance and role of the Cultural Support Team alongside other reliable and trusted sources of information during a pandemic.

Barriers and challenges

Some participants mentioned how it was a challenge for some families to safely isolate due to large families and inadequate housing, which is consistent with other research where generations live under one roof (Clements et al. 2023). Some participants noted that literacy barriers in understanding public health messages and the inconsistent delivery of resources, such as food boxes, created inequities and gaps in support. One participant shared that homeschooling was hard because of their own low literacy and lack of support. Health literacy and technical support may assist people to understand the reasons for the public health measures and promote and encourage behaviour change (Häfliger et al. 2023; McCaffery et al. 2020; Paakkari and Okan 2020).

Addressing system inequities

Mainstream health services are often an unsafe place to seek healthcare (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2023). Some participants reflected on the historical and ongoing effects of colonisation and assimilation and the fear of child removal as a barrier to accessing healthcare. The Cultural Support Team’s experience and understanding of the issues Aboriginal peoples experience ensured that the team’s planning and response efforts identified and addressed these issues. Being an all-Aboriginal team, efforts were made to ensure Aboriginal cases and contacts felt supported, not reported (Dudgeon et al. 2023). An analysis of the COVID-19 policy response constructs Aboriginal people as vulnerable and mobility as a problem that needed a law-and-order response (Donohue and McDowall 2021). Deficit discourse frames and represents Aboriginal peoples in a narrative that is negative and problem blaming (Chittleborough et al. 2023). To avoid being referred to as ‘poor historians’, having ‘poor recall’ or being ‘non-compliant’, Aboriginal public health leaders ensured that Aboriginal people were included early and not forgotten (McCalman et al. 2021).

Incorporating holistic care into the cultural support model highlights the team’s role in acknowledging and addressing fear of disclosing personal information, which is deeply rooted in past policies and practices of forced child removals. Aboriginal people are still fearful of having their children removed due to these experiences (Dudgeon and Walker 2022). By embedding this understanding into the cultural support model to guide conversations with families, we demonstrated the potential of culturally informed care to mitigate intergenerational trauma of assimilation policies. This approach aligns with findings from studies that emphasise the importance of culturally safe and responsive healthcare to build trust with Aboriginal communities (Graham et al. 2022).

Some participants noted the importance of data sharing and understanding local contexts and situations regarding COVID-19 case numbers. Data sharing had been a longstanding barrier that was easy to remove during the pandemic. However, concerns remain that data sharing was no longer in place (Scheibner et al. 2023). Effective information is crucial to identify and activate local support services and should not be limited to state and national governments but should include Aboriginal communities. This approach ensures that local contexts are understood and addressed, leading to effective public health responses underpinned by shared decision-making and self-determination (Jull et al. 2023). Several frameworks emphasise the need for Aboriginal people to exercise greater control over their data (Data Champions Network Working Group 2024; National Indigenous Australians Agency 2022; Rose et al. 2023) while acknowledging and addressing the historical contexts and considers Indigenous data needs (Walter et al. 2021).

Strengths and limitations

There were many strengths of this study. We centred Aboriginal voices and cultural values by conducting research that was informed by Aboriginal people. This enabled the lived experiences of Aboriginal people to come through, ensuring the findings are meaningful for communities. Both quantitative and qualitative research methodologies, underpinned by Indigenist research and participatory action research approaches, provided deeper understandings of Aboriginal people’s experiences of cultural support, allowing valuable insights and suggestions for future pandemic responses. The study captured diverse perspectives and experiences including age, gender and geographical location, to enhance the richness of the findings.

This study had several limitations, including missing or incomplete data for some questions. A key limitation was the considerable time gap between when cultural support was provided (March 2020 to January 2022) and when the study was conducted (April to November 2024). Participants did not indicate when they received cultural support, making it difficult to understand the average time between when individuals were provided support and participation in the survey and yarn. This may have affected recall bias and participant ability to accurately reflect on their experiences. Moreover, there were challenges in follow-up with potential participants for both the survey and yarns, such as disconnected and changed phone numbers, which reduced the ability to reach more people. These factors hindered our ability to understand a wider range of experiences, however, the depth of the insights collated provided valuable learnings and guidance. Some participants may have only shared positive feedback in the yarning session, given that the Aboriginal researchers were also part of the Cultural Support Team. However, we believe participants felt comfortable enough to provide honest feedback. The use of Indigenist research methods, including yarning, ensured participants experiences and perspectives were privileged and contextualised within sociocultural realities. Also, the recruitment approach ensured a diversity of voices.

Recommendations for pandemic policy and practice

Embed cultural governance

Embedding cultural governance and the Aboriginal cultural support model was relatively smooth due to the commitment to privilege Aboriginal representation and ways of doing in the local Public Health Unit (Crooks et al. 2021). However, without the leadership of non-Aboriginal peoples, implementing similar models within a mainstream public health unit may not be as easy or achievable. The success of the cultural support model was attributed to it being led by Aboriginal peoples within a culturally appropriate governance framework (Griffiths et al. 2021). Mainstream public health units could adopt similar approaches by fostering local partnerships with Aboriginal stakeholders, invest in cultural safety and competence training for non-Aboriginal staff and align public health emergency responses with Aboriginal worldviews. Without sustained efforts, Aboriginal peoples’ needs and priorities may continue to be overlooked, which can often perpetuate systemic racism and health inequities (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2023).

Strengthen Aboriginal leadership and partnerships

Strengthening Aboriginal leadership and partnerships can be achieved by investing in an Aboriginal public health workforce and collaborating with ACCHOs to deliver local responses (Wilson‐Matenga et al. 2021)

Tailored and targeted communication

Tailored communication allows for reliable, accessible and culturally relevant information to be developed and disseminated through local and trusted sources, like Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services and other Aboriginal organisations.

Identify and address systemic barriers

Identifying barriers ensures reliable systems and processes are in place to support individuals, families and households (for example food boxes, household cleaning products).

Embed Aboriginal cultural support models in public health practice

Public health should invest and resource programs like the Aboriginal cultural support model to ensure Aboriginal peoples and communities are supported during public health crises like pandemics.

These recommendations support and align with national and state reforms, priorities and plans (Coalition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peak Organisations and Australian Government, 2020; Centre for Aboriginal Health 2024; Department of Health and Aged Care 2021). Sustained investment and efforts are needed to resource public health efforts and build, strengthen and retain an Aboriginal public health workforce to appropriately and adequately plan and respond to public health emergencies in a timely way. Future research could explore the experiences and perspectives of health staff involved in delivering the cultural support model as well as examining best practices for delivering culturally appropriate public health communications with Aboriginal communities.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates the importance of embedding Aboriginal-led, informed and tailored cultural support into public health emergency responses These findings help to inform future public health responses and improve outcomes for Aboriginal peoples. The study highlights the successes of cultural support and provides a model that can be tailored, adapted and replicated in other regions or small or large public health incidents and emergencies.