This case study summarises key outcomes from a collaborative research project conducted in the Illawarra, NSW in 2017. It outlines ways to inform, engage and partner with people from diverse refugee backgrounds for strengthening disaster resilience.

The project, ‘Resilient Together: Engaging the knowledge and capacities of refugees for a disaster-resilient Illawarra’, responds to a gap in current understanding on how people from refugee backgrounds learn about natural hazards and find safety as they settle into new homes and cities.

The Illawarra is a coastal region comprising the Wollongong, Shellharbour and Kiama local government areas. The project presents important insights for disaster resilience as the Illawarra, a ‘Refugee Welcome Zone’, accommodates new and emerging communities and prepares for climate changes in the coming decades.

The research objective was to understand the diverse experiences, beliefs and everyday practices for disaster resilience among people from culturally and linguistically diverse refugee backgrounds.

Methodology

Following ethics approval from the University of Wollongong Human Research Ethics Committee (ref. HREC 2017/268), the project adopted a two-pronged approach from June to September 2017. With support from Wollongong City Council, the University of Wollongong conducted consultations with 12 local emergency and multicultural agencies and service providers in the Illawarra. The objective was to understand the operating environment in which daily and emergency support is provided for newly arrived and recently settled people from refugee backgrounds. In addition, with assistance from the Illawarra Multicultural Services and the Strategic Community Assistance to Refugee Families, the University of Wollongong conducted semi-structured interviews with 26 people from diverse refugee backgrounds, namely Burma, Congo, Iran, Iraq, Liberia, Syria and Uganda. At the time of the interviews, research participants had been living in the Illawarra for periods of at least six months and up to 15 years. Interviews were conducted at a time and place chosen by the research participants. Interviews were facilitated by community interpreters hired by the project. They were audio recorded with prior verbal or written consent from the research participants.

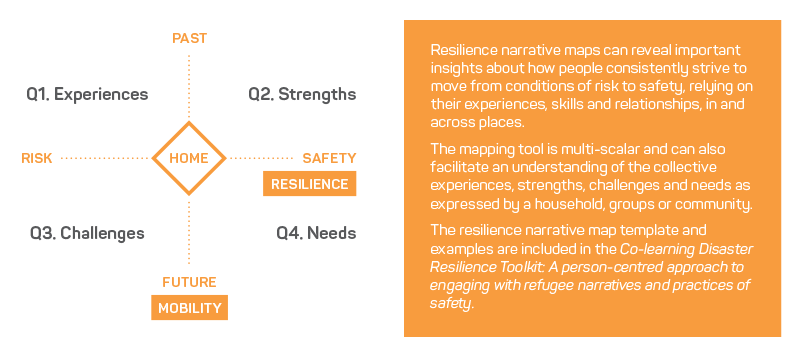

The interviews were transcribed verbatim for analysis. The interview transcripts were anonymised and systematically plotted using a person-centred mapping tool to create resilience narrative maps (Figure 1). The resilience narrative maps show how people strive to move from conditions of risk towards safety, while relying on their past experiences, capacities and relationships.

Findings

The research revealed three particular and unmet needs in the Illawarra. Firstly, people from refugee backgrounds do not have ready access to local hazard and risk information. Ten of the 26 participants reported being caught unaware by bushfires, flash flooding, hail, heavy rain, lightning and strong winds during their first year of living in the Illawarra. Secondly, nine of the 26 participants reported having lived in what they perceived was unsafe, insecure and low-quality housing during the first months of living in the Illawarra. Finally, the research found that people from refugee backgrounds do not receive timely and culturally and linguistically relevant information and training on issues of personal safety and home preparedness.

Figure 1: Resilience narrative map template used in this study.

Key outcomes

Research findings were presented to eight participating institutions1 and 22 community representatives at a workshop in November 2017. During workshop discussions, participants acknowledged the general lack of partnerships between local emergency services, settlement and multicultural services, community-based organisations, places of worship and community leaders. As such, there was no effective outreach and connection with new residents from refugee backgrounds. The research found that local settlement and multicultural services can play a key role in informing newly arrived entrants of local hazards and risks, and how to access safe housing in secure locations, as they are often the first point of contact on arrival. Research participants also emphasised the need for in-home preparedness training and support for socially and physically isolated individuals, especially the elderly and women with young children, in their first language and from a trusted member of the community.

In response to these findings and recommendations, NSW SES invited 20 people from diverse refugee backgrounds to participate in a fast-track training program to form the NSW SES Multicultural Liaison Unit. The unit comprises multicultural community liaison officers from diverse refugee backgrounds. These liaison officers receive ongoing training to support their role and strengthen community capacity to respond to emergencies including flooding, fires and storms. The unit also allows the NSW SES, through the liaison officers, to better reach out to people from refugee backgrounds with hazard and safety information in a timely, relevant and culturally appropriate way. The liaison officers also provide a sustained mechanism for sharing community safety concerns and suggestions with local councils and emergency services.

Conclusion

This research demonstrates how local councils, emergency services, multicultural services and research institutions can effectively engage and partner with new and emerging communities to strengthen disaster resilience. Future work in this area includes designing and implementing more collaborative, accountable, responsive and empowering programs and services with people from diverse refugee backgrounds.