OPINION- Promoting resilience-a contemporary and integrated policy and funding framework for disaster management

Jim McGowan AM

Jim McGowan AM, Adjunct Professor, Griffith University, argues there are new imperatives to drive policy reform for better funding for disaster management

Article

The Federal Government’s announcement of a Productivity Commission inquiry into disaster management arrangements is welcomed. This provides a once-in-a-generation opportunity to build a resilience-based policy framework. A purposeful and methodical review of the policy and funding frameworks would facilitate the development of a contemporary and integrated model for disaster management across Australia. The current frameworks need to be reframed in a manner consistent with the strategic policy objective of promoting greater individual and community resilience. Rather than tinker with existing funding arrangements, a ‘root and branch’ review of the policy and funding frameworks for the prevention, preparedness, response and recovery phases of a cost effective regime for the management of natural disasters is required.

The August 2013 report from the Regional Australia Institute (RAI) entitled From Disaster to Renewal: The Centrality of Business Recovery to Community Resilience1 presents a major challenge for policy makers. It argues that recovery from a natural disaster needs to be viewed within a broader framework of resilience, moving beyond the traditional focus on relief and reconstruction to incorporate local renewal and adaption strategies so that affected communities can adapt to their post disaster circumstances.

The From Disaster to Renewal report draws on the experiences of four towns, Cardwell and Emerald in Queensland and Carisbrook and Marysville in Victoria, recovering from natural disasters.

The report highlights the inconsistency between many of the strategies to assist communities to recover from a natural disaster event and the objective shared by all tiers of government—to build an Australia that is more resilient to natural disaster events that are expected to become both more frequent and more severe. COAG adopted the National Strategy for Disaster Resilience (NSDR) in February 2011. The NSDR advocates ‘a whole-of-nation resilience-based approach to disaster management, which recognises that a national, coordinated and cooperative effort is needed to enhance Australia’s capacity to withstand and recover from emergencies and disasters’.2

It provides not only an aspirational framework for disaster management but also reflects the outcome of a co-operative approach to natural disasters involving Commonwealth, state and territory and local governments.

However, if the policy imperatives are ‘Resilience’ and improving individual and community understanding of risk, reframing the policy and funding frameworks for disaster management is critical. Building resilience requires the integration of all the prevention, preparedness, response and recovery (PPRR) phases. Each of the four phases should provide feedback loops to improve performance, policy development and resourcing priorities. Currently these feedback loops are poorly developed, as evidenced by the disproportionate funding allocations between the response and recovery phases and the prevention and preparation phases. The policy implications of the policy and funding gaps have long-term implications. Currently they not only create significant demands on Federal and State budgets, but also have long-term impacts on national productivity and economic performance.

‘In 2012 alone, the total economic cost of natural disasters in Australia is estimated to have exceeded $6 billion. Further, these costs are expected to double by 2030 and to rise to an average of $23 billion per year by 2050, even without any consideration of the potential impact of climate.

Each year an estimated $560 million is spent on post disaster relief and recovery by the Australian Government compared with an estimated consistent annual expenditure of $50 million on pre-disaster resilience: a ratio of more than $10 post-disaster for every $1 spent pre-disaster.’3

The commitment to and investment in prevention and mitigation has been miserly in comparison to the expenditure of response and reconstruction, despite evidence of the economic returns and resilience benefits that can be expected from such investments. Research from the Bureau of Transport Economics in 2002 showed that flood mitigation can provide a 3:1 return on investment through the avoidance of response and recovery costs. In the USA there is research which shows a 5:1 average return on flood mitigation investment.

The interest by the private sector in the policy frameworks for disaster management is a welcome development. The Australian Business Roundtable for Disaster Resilience and Safer Communities has also called for a commitment ‘to long term annual consolidated funding for pre-disaster resilience and to identify and prioritise pre-disaster investment activities that deliver a positive net impact on future budget outlays.’ In advocating for a more formal involvement by the private sector it recommends the appointment a National Resilience Advisor and the establishment of a Business and Community Advisory Group (Deloitte p. 51).

The RAI report also challenges the traditional narrow focus of ‘Recovery’ from natural disasters. Although community recovery is dependent on business recovery, experiences in Australia and internationally often treat the recovery phase as having too short a time horizon, focusing predominantly on relief and reconstruction (RAI 2013 p. 21).

Policy and funding frameworks for recovery need to be rethought with a much longer-term focus. The RAI report argues that:

‘Recovery arrangements need to be viewed within a resilience framework, which moves beyond relief and reconstruction to incorporating local renewal and adaption to the post disaster environment.’

(RAI 2013 p. 2)

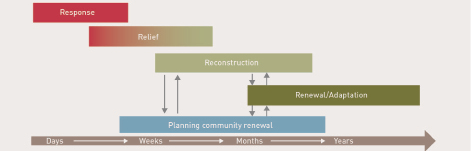

Figure 1 attempts to highlight the different phases of recovery, the relative timing, and the relationships between them.

Figure 1: Phases of recovery

(Source: Adapted from RAI 13 p. 9)

The origins of this policy and funding incoherence, in part at least can be attributed to the overwhelming focus by all three levels of government on the National Disaster Relief and Recovery Arrangements (NDDRA) and the Australian Government Disaster Recovery Payments (AGDRP) to affected individuals (‘hardship grants’). The NDDRA had its origins in Commonwealth and state negotiations dating back to Cyclone Tracy in 1974.

In addition to these Commonwealth ‘hardship grants’ state governments provide cash grants to impacted individuals and families. Generally these national arrangements served communities affected by natural disasters well by providing certainty and clarity as to the type and extent of the support from the various levels of government.

However these arrangements were developed in an era in which the number and impact of disasters was considerably less than has occurred in the last decade. They are reactive in that they are triggered by an event and are consequently focussed on response and the initial recovery. This also reflects when political and media attention is strongest.

There are also policy and operational limitations for the NDRRA. The arrangements are administratively complex. The RAI report notes that the NDRRA

‘generally covers restoration of public infrastructure, (but) does not provide funding for the restoration of the natural environment. This reflects a lack of recognition of the importance of the natural environment component of business recovery. Environmental restoration works were seen as important as the reconstruction of hard assets to business. This is particularly the case where tourism based on the natural environment is a significant contributor to the local economy. Businesses in Cardwell and Marysville rely on the natural environment as the regional “drawcard”.’ (RAI 2013 p. 13)

There are examples where roads, bridges and other critical infrastructure have been repaired using NDRRA funds only to be swept away in the next flood. Current arrangements involve the restoration of those assets. This is shortsighted and ultimately more expensive. The ‘betterment provisions’ were included in the NDRRA in 2007. However,

‘Despite multi-billion dollar recovery bills, it appears that the betterment provisions …have not been widely accessed. Government infrastructure and assets are still being rebuilt like for like and, notwithstanding incremental improvements in design, this misses the opportunity to fundamentally rethink the vulnerability of key infrastructure and plan accordingly.’

(RAI 2013 p. 11)

‘Betterment’ arrangements are consistent with building resilience. Engineered properly, they constitute a more cost effective investment strategy through the avoidance of future response and recovery costs. After a disaster event, the default position should be to rebuild the infrastructure so that it is better able to withstand the next event rather that the current predisposition to restore assets to their previous state.

In relation to the AGDRP, the Report notes

‘Hardship grants, unless carefully structured and targeted, have the potential to undermine the community resilience that sits as the core objective of the National Strategy on Disaster Resilience.’

(RAI 2013 p. 16)

To re-iterate, the NDRRA and AGDRP have been beneficial, particularly to individuals but they preceded the NSDR. It is timely to revisit these arrangements, given the findings and recommendations of the From Disaster to Renewal and the Building our nation’s resilience to natural disasters reports.

The report summarises the finding from research in communities recovering from and adapting to the impact of disasters.

The policy, support and funding arrangements need to be derived from the NSDR and based on the interaction of the prevention, preparedness, response and recovery obligations of all levels of government, local communities, the private sector and individuals. In these times of economic austerity, the imperative of a coherent and comprehensive approach to natural disasters is even more pressing. This is not a cry for additional resources to support the response to and recovery from a natural disaster but rather the redirection of some of these resources to promote community resilience through mitigation strategies and more focused approach to community recovery that recognises business recovery as a pre-condition for that recovery.

Having developed the NSDR, the new imperative is to drive the policy reform processes to give effect to its noble aspirations of building a resilient Australia. Policy and funding frameworks can promote the greater personal and community resilience though the development of a more cost effective and robust approach to how all Australian jurisdictions can respond to current and future challenges caused by the inevitable natural disasters which will impact on the nation.

1From Disaster to Renewal: The Centrality of Business Recovery to Community Resilience, Regional Australian Institute, August 2013. The research was conducted in collaboration with Griffith University and affected towns and communities. Reports and other material from the project are available at www.regionalaustralia.org.au.

2Full report available at www.em.gov.au/Documents/1National%20Strategy%20for%20Disaster%20Resilience%20-%20pdf.PDF.

3Deloitte Access Economics 2013, Building our nation’s resilience to natural disasters - a paper for Australian Business Roundtable for Disaster Resilience and Safer Communities, p8. At: www.australianbusinessroundtable.com.au.