Emergency management in Australia continues along a path of professionalisation. To support that process, a range of activities must be completed and research into the human capacities of the emergency manager role in Australia was undertaken. Emerging from that research is the Emergency Management T-Shaped Transdisciplinary Model. The model provides a framework for the selection, development and recognition of the defined roles of Emergency Manager, Response Manager and Recovery Manager. By using the Emergency Management T-Shaped Transdisciplinary Model the key roles can be identified, discussed, evaluated and adopted. Thus, the development of these roles are described and provide a means to develop understanding of the roles and underlying human capacities requires training, education, certification and policy to be developed and applied in a consistent manner. This will support future emergency management practitioners as well as the professionalisation of emergency management in Australia.

Introduction

Emergencies and disasters affect communities on an ongoing basis. In Australia, the Major Incidents Report (AIDR 2017, p.3) documented 9 major incidents during 2016–17. However, the 2023–24 report showed the number of incidents had risen to 30 (AIDR 2024, p.1). This increase affects individuals, communities and the environment in disparate ways. Individuals may be injured or killed, communities can lose members and the contributions of those individuals to the fabric of the community and the environment may be affected for a short or a long time. There is a rising expectation that the people who have roles to prepare for, respond to or recover from emergencies and disasters have appropriate knowledge, skills and abilities so they can ameliorate the effects of these events.

Emergency management in Australia is undergoing a process of professionalisation (Dippy 2022, p.72). Professionalisation requires a range of activities to be undertaken including the building of extensive theoretical knowledge and legitimate expertise, application of a code of ethics, possession of an altruistic commitment to service and application of a level of autonomy (Peterson 1976, p.573; Yam 2004, p.979). Certification, education and training have been previously explored by Dippy (2020, p.56; 2022, p.68) and forms part of the journey of professionalisation of emergency management in Australia. Exploration of the definitions that can be applied to emergency managers, response managers and recovery managers (Dippy 2025b, p.66) and the concept of disciplines and disciplinary models (Dippy 2025a, p.6) also underpin the development of personnel who lead the prevention of, preparedness for, response to and recovery from emergency events. This paper brings together this previous work on professionalisation into a model, the Emergency Management T-Shaped Transdisciplinary Model, that is a framework to develop future emergency management leaders.

Background

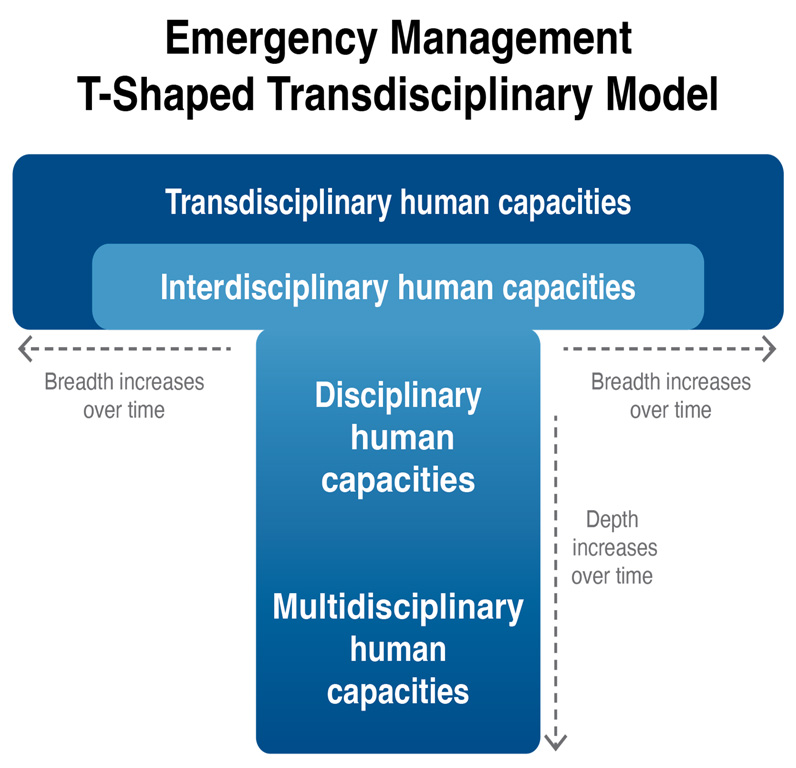

The research to determine the human capacities of the emergency manager in Australia was analysed and the concept of the Emergency Management T-Shaped Transdisciplinary Model was developed. The model incorporates the previously identified definitions of the Emergency Manager, Response Manager and Recovery Manager (Dippy 2025b, p.66). The model also incorporates the concept of emergency management disciplines and the Emergency Management Disciplinary Spectrum that emerged from this research (Dippy 2025a, p.6).

Leaders and managers have been described in the literature using several shape-based analogies for many years. The ‘T-shaped’ analogy was first used in 1991 by Professor David Guest in the description of an information technology professional (Guest 1991). Johannessen et al. (1999, p.128) expanded the understanding of the analogy in their exploration of knowledge management innovation to describe T-shaped people as those with combined theoretical and practical knowledge that was systemic in nature and spanned multiple ‘branches of knowledge’. This understanding was used by Johannessen and colleagues to propose a typology of knowledge in the innovation sphere (Johannessen et al. 1999, p.128). While Johannessen et al. (1999) present the typology as a quadrant-style model, the concepts of depth and breadth of knowledge that underpin the T-shaped leader remain. Johannessen et al. (1999) state that the innovative concept supports improvement of company competitiveness, knowledge development and integration to generate new knowledge (p.134).

Hansen and von Oetinger (2001) furthered the understanding of T-shaped management with their exploration of the concept’s application in the multi-national petroleum company, BP. The company was an early adopter of the concept of T-shaped managers and this has shown clear benefits of the practice (p.109). Hansen and von Oetinger (2001) examined the concept of T-shaped managers from the perspective of behaviours, unlike previous explorations that were about skills. The authors explicated the concept with the sharing of knowledge occurring across the horizontal part of the ‘T’ as separate from the manager’s deep individual expertise of their area represented by the vertical part of the ‘T’ (p.108).

Lee and Choi (2003) examined knowledge management enablers and processes and hypothesised a positive relationship between the presence of members with T-shaped skills and knowledge creation. They examined major Korean companies and found that T-shaped skills did not affect knowledge creation per se (p.6), but that knowledge creation is associated with cultural factors of collaboration, trust and learning (p.210). Further, they found that the systematic management of T-shaped skills in a T-shaped management system is a crucial element of successful knowledge management (p.213).

Glushko (2008) examined the 2003 emergence of service science as a discipline that was developed in partnership between the University of California, Berkeley and IBM. Service science builds on concepts of multi-disciplinary or trans-disciplinary activities when moving towards a service-based economy (Glushko 2008, p.16). In this development, it was noted that T-shaped people were essential in service areas, but that the definition of the skills held by those people was still fluid and contentious. It was noted that descriptions of the T-shaped person that arose included being empathetic, having the ability to apply different perspectives (i.e. breadth of skills) and having deep business skills and technical understanding; that is, depth of skills (Glushko 2008, p.6).

At the same time as Glushko’s work with IBM, a parallel exploration was occurring in universities in Finland as part of student development for strategic design management (Karjalainen and Salimäki 2008). Three universities worked to understand the application of both wide strategic skills and deep technical expertise while noting that the typical university education only addresses deep technical skill development (p.2). The universities separated the skills on the vertical and horizontal strokes of the ‘T’. The vertical stroke represented discipline-specific information. The horizontal was the interactions of their specific discipline with the other disciplines required for the project (p.6). The T-shaped person was separated from the ‘expert’ who had strong knowledge and expertise in their own area only, and also from the ‘generalist’ (or wide professional) who had some non-expert knowledge across disciplines (p.7). In this analogy, the generalist would be represented by the horizontal bar of the ‘T’; that is, the person with the breadth of skills and the expert by the ‘I’ for their depth of skills.

The use of vertical and horizontal descriptors has been applied in learning environments without the use of the T-shaped analogy. Postma and White (2017) and Snymam and Kroon (2005) used the terms in dental education where vertical training involves very specific topic-based knowledge (e.g. the exterior of a tooth) and horizontal training is about the holistic management of the patient. Dulloo et al. (2017) applied a similar methodology to medical students and Klein (2016) applied this to the education of teachers. By combining vertical (topic specific) and horizontal (broad disciplinary context) teaching it was found that a better overall training outcome was achieved for dentists, doctors and teachers.

In recent times, the use of the T-shaped analogy has expanded in the fields of marketing (Rust et al. 2010), engineering (Elmquist and Johansson 2011; Nesbit 2014), project management (Fisher 2011), water professionals and hydrologists (McIntosh and Taylor 2013a, 2013b; Ruddell and Wagener 2015; Sanchez et al. 2016; Uhlenbrook and De Jong 2012), the service economy (Barile et al. 2015; Demirkan and Spohrer 2015), innovation (Jimenez-Eliaeson 2017) and, most recently, in higher education (Rippa et al. 2020; Saviano et al. 2017).

The T-shaped person has now been explored in US and European contexts. Its use has expanded from a concept to being applied in major multi-national companies. It is being applied in engineering-based industries, including in Australia (McIntosh and Taylor 2013a, 2013b) as well as in academia. This expansion of its use has occurred over a period of 30 years.

The concept of a T-shaped person has matured and was described by Uhlenbrook and De Jong (2012) as a person who is ‘a top expert in one field, but he or she can build bridges to other disciplines and is able to think outside the box’ (p.3478). Uhlenbrook et al. (2012) described the vertical bar as representing a deep understanding of a particular discipline with the horizontal bar representing knowledge, values, ethics, functional, personal and cognitive competence arising from other disciplines. Hansen and von Oetinger (2001) described the horizontal bar as one that represents collaboration; the giving and taking advice and connecting with others (p.111). Both Jimenez-Eliaeson (2017, p.51) and Guimarães et al. (2019) describe this horizontal set of skills as ‘transdisciplinarity’ or being ‘interdisciplinary’. Chan et al. (2020, p.115) summarised all these descriptions to refer to someone who has a deep specialisation (vertical) and broad knowledge and skills (horizontal).

Research methodology

This study examined the question: ‘What human capacity demands should inform the development and appointment of an emergency manager?’.

A 20-year period of emergency event inquiry reports were examined. The period between 1997 and 2017 was used because many contemporary emergency management concepts and principles have been in place since 1997. Before this period of practice, the response to emergencies was based on cold-war-era civil defence paradigms (Emergency Management Australia 1993, p.3). Since 1997, considerable change has occurred. The introduction of incident management systems by bodies such as the Australasian Fire and Emergency Services Council (AFAC) (2017), the Australian and New Zealand Policing Advisory Agency (ANZPAA) (2012) and biosecurity agencies (DAFF 2012) as well as the introduction of the National Strategy for Disaster Resilience (Commonwealth of Australia 2011) and the National Emergency Risk Assessment Guidelines (National Emergency Management Committee 2010) have led to major changes in the emergency management environment in Australia.

The reports analysed for this research were all judicial or semi-judicial in nature. Judicial inquiries occur in a legal environment such as criminal or coronial courts. Semi-judicial inquires, including royal commissions and formal legislated inquires, have a legally enforceable requirement to answer questions and provide information. Judicial and semi-judicial inquiries are conducted for emergency events and disasters that have significant effects on communities based, in part, on their complexity or consequences. The inquiry reports identified a range of human capacities of the emergency manager. Interviews were conducted with authors of 8 emergency event inquiry reports to identify further human capacities required in the management of emergency events.

The literature review incorporated broader management concepts in conjunction with the emergency event inquiry reports. The analysis of the practical and theoretical information sources led to the distillation of themes within the identified human capacities. The interviews provided further human capacities that deepened the thematic analysis of the human capacities applied by emergency managers.

A Gadamerian philosophical hermeneutic research methodology was applied (Gadamer 2004, 2013; van Manen 1997). The interviews of emergency event inquiry authors, examination of emergency event inquiry reports and the literature review generated over 15,000 pages of text. The Gadamerian methodology acknowledged the researcher’s participation in the field and any potential effect to the analysis of the text. The application of the Gadamerian methodology allowed rigorous analysis to occur that included acknowledgment of the researchers world view (Gadamer 2004, p.xi; van Manen 1997, p.197) within the process of documentation, reflection, reconsideration and change in a manner that was captured and acknowledged. The application of Gadamer’s analysis methodology allowed rigorous and replicable findings to emerge from the research.

This paper presents the Emergency Management T-Shaped Transdisciplinary Model that emerged from the analysis. The model brings together the range of concepts and definitions into a pictorial representation that can be used for future development of people who take on leadership roles for emergency events.

Ethics statement

This research received approval from the Charles Sturt University Human Research Ethics Committee (Approval #H19294).

Findings

The Emergency Management T-Shaped Transdisciplinary Model provides a developmental framework for current and future emergency managers, response managers and recovery managers. The model consolidates the defined terms of Emergency Manager, Response Manager and Recovery Manager (Dippy 2025b) and the Emergency Management Disciplinary Spectrum (Dippy 2025a) with the analysis of the literature explored and human capacities that arose from this research.

Figure 1 illustrates the model and shows the application of disciplinary human capacities to the T-shaped leadership concept.

The Emergency Management T-Shaped Transdisciplinary Model was developed as a means to collate and apply identified human capacities. The model consists of a vertical component indicating the depth of human capacities and a horizontal component indicating breadth of human capacities.

Discussion

The development of the Emergency Management T-Shaped Transdisciplinary Model included analysis and theming of the human capacities identified in the research. The themed human capacities support the model. The themes identified from the human capacities also support the training and development of future emergency managers, response managers and recovery managers. Further, the themes provide a framework from which existing emergency managers, response managers and recovery managers can undertake additional personal development and from which public and private organisations can develop their programs and staff (including paid and unpaid staff).

T-shaped leaders were identified by Guest (1991) in relation to the work of information technology professionals (the use of the term ‘professional’ by Guest (1991) related to full time paid staff in information technology, not a recognised profession (as described earlier). This work was later expanded by Johannessen et al. (1999, p.128) who proposed a typology of knowledge for people applying T-shaped skills; people who have both theoretical and practical knowledge across multiple branches of knowledge. The term ‘multiple branches of knowledge’ is the same as the concept of trans-disciplinarity applied to the emergency manager role and described in the Emergency Management Transdisciplinary Spectrum (Dippy 2025a). In essence, the concept of trans-disciplinarity involves multiple disciplines being applied to the resolution of a problem. Trans-disciplinary skills arise from multiple disciplines or branches of learning being applied to the overall emergency event. The emergency manager applies trans-disciplinary skills and knowledge to the prevention of, preparedness for, response to and recovery from an emergency event.

Branches of knowledge also align with the concept of breadth of knowledge that arose in this research. It was identified that an emergency manager requires a broad range of knowledge, skills and abilities. This range or breadth of knowledge, skills and abilities includes developing plans, applying lessons identified, supporting and/or implementing plans, managing community recovery from an emergency event and undertaking lessons management processes. Each of these tasks are based on different areas of knowledge. For example, developing plans may require information relative to the hazards that may result in an emergency event. The hazards that the emergency manager develops plans for include weather-based events, fires, cyber-security events and biosecurity events. Recovery actions may require information arising from human behaviour knowledge bases. Each of these examples is supported by different disciplines or branches of knowledge.

Guimarães et al. (2019) discussed the development of inter- and trans-disciplinary research, noting the need for ‘disciplinary depth, multidisciplinary breadth, interdisciplinary integration and transdisciplinary competencies (i.e. T-shaped training)’ (p.112). This union of trans-disciplinarity and T-shaped learning was also described by Jimenez-Eliaeson (2017, p.51) who posited that a lack of T-shaped learning reduces trans-disciplinary skills and, thus, the number of innovators in the community. Rippa et al. (2020) showed that T-shaped PhD learning methods had positive effects on vertical skills and horizontal capabilities (i.e. transdisciplinarity) of students (p.13).

Connecting the concepts of disciplinarity and T-shaped leadership and learning produces a model that can be applied to emergency management and emergency managers. The model positions disciplinary skills in the vertical component of the T-shape. The vertical component includes the multi-disciplinary aspect of an emergency as it is the joint application of 2 distinct sets of disciplinary skill sets. The horizontal component of the T-shape consists of the inter-disciplinary skills (a small horizontal sub-component only) with the full horizontal component being the trans-disciplinary skills. When the 4 parts of disciplinarity and the overall T-shape are combined, the model emerges as shown in Figure 1.

Bierema (2019) examined T-shaped professionals (referring to engineers, teachers and artists) and identified a range of horizontal skills that included:

…inquiry, open mindedness, curiosity, compassion, teamwork, communication, listening, emotional intelligence, networking, critical thinking, holistic understanding, organisational skills, program management, perspective, global thinking, cultural competence, resilience.

(p.69)

Figure 1: The Emergency Management T-Shaped Transdisciplinary Model.

Bierema (2019) also noted that the horizontal skills list is not common to all disciplines, but that each discipline’s required knowledge, skills and attitudes (their human capacities) should be identified according to need (p.69). Augsburg’s (2014) transdisciplinary researchers were noted to have qualities (human capacities) ‘such as curiosity about, and willingness to learn from, other disciplines; flexibility; adaptability; openness in mind; creativity; good communication and listening skills; capacity to absorb information; and teamwork’ (p.238).

The human capacities discussed by Bierema (2019) and Augsburg (2014) of teamwork, networking and holistic understanding have commonalities with emergency management (e.g. open mindedness, communication, listening and curiosity). These and other similar human capacities arose during the interviews in this research. The following comments from interviewees noted empathic listening, critical analysis, understanding society, team building, inquiring mind, courage and resilience support. The human capacities identified by the interviewees included human capacities that arise in both the transdisciplinary model and the horizontal aspect of a T-shaped person:

…an empathic listener. So that’s 2 concepts of course, one is to be a listener and the other is to do it with empathy.

(Interview 3)…you need to be critically analysing all the time, and therefore you need to adapt to the situation and be comfortable that, your change in strategy is going to meet the outcome.

(Interview 7)…but they are the ones that understand what the fabric of society is, and that really to me are the people that come to the fore.

(Interview 5)…where you will actually sit down as a team and you will decide the next steps, and it’s not abrogating your leadership its actually engaging the team to get them, I guess, communicate to them what you are doing and how you’re going to go about it.

(Interview 4)…someone who has an inquiring mind, who is able to clearly articulate strategy, clearly articulate what his or her expectations might be, and to commence that dialogue.

(Interview 1)…so, I think some of those people have displayed enormous courage and resilience.

(Interview 2)

Based on these interviews, the model of T-shaped leadership was applied in conjunction with the transdisciplinary model of the Emergency Manager, Response Manager and Recovery Manager (Dippy 2025a). Noting Bierema (2019), that the skills forming the horizontal aspect are not the same across disciplines, the human capacities identified during this research were used to form the horizontal and vertical aspects of the newly applied T-shaped model. The human capacities were analysed and applied to the concepts of breadth of skills and depth of skills.

For the purposes of this research, definitions were established for both breadth and depth. Depth was defined as a ‘skill or behaviour that is developed over a period of time, education or experience within a particular discipline’. Breadth was defined to be a ‘skill or behaviour that is applied when working across disciplines’. Applying Bierema’s (2019) observation that the transdisciplinary skills should be identified for each discipline (p.69), the human capacities identified as breadth are the trans-disciplinary human capacities applied to the T-shaped emergency manager.

Further review of the human capacities listed as related to breadth led to the development of themes including:

- unbounded problem analysis and problem-solving skills including the application of hazard and community information

- understanding of the broad cardinal effects of an emergency event

- ability to communicate omnidirectionally in the management of the emergency

- ability to develop, integrate and lead multi-community teams

- high levels of emotional intelligence

- understanding of risks and the ability to avoid risk paralysis

- self-understanding of skills and abilities and the means of supplementing them with a team-based approach

- understanding and experience of leadership and management styles and the appropriate application of each.

The themes identified in the human capacities aligned with the concept of breadth contain similarities to those identified by Bierema (2019) and Augsburg (2014) but they also contain aspects that are unique to the Emergency Manager, Response Manager and Recovery Manager.

To complete the development of the T-shaped model, it is appropriate to examine the human capacities that form the basis of the disciplinary and multi-disciplinary vertical component of the T-shaped model. The human capacities identified as being aligned with the concept of depth are not discipline-specific but could apply to all disciplines that form the basis of the work of the Emergency Manager, Response Manager and Recovery Manager.

On reviewing the human capacities aligned to the concept of depth, the following themes emerged:

- knowledge and understanding of the tactical, operational and strategic aspects of the discipline and organisation

- identification and application of disciplinary and non-disciplinary resources while acknowledging the limitations of those resources

- exhibits a presence that includes leadership, command, openness, confidence, acceptance of responsibility and calmness

- judgement based on ongoing self-development, experience, education, qualification and certification

- ability to communicate omnidirectionally in the management of the emergency

- decision-making in the face of stressors of time and limited information.

The human capacity of communication is present in both the vertical (disciplinary) and horizontal (trans-disciplinary) aspects of the model. While being unable to separate this human capacity into a single category may be considered a fault in the analysis, it occurred because of the importance of communication in bringing together both aspects of the role of the emergency manager and the response or recovery manager. The transcending of communication between the disciplinary and transdisciplinary aspects joins the 2 parts of the model, forming the T-shape and not just a vertical box and a horizontal box placed alongside each other.

The logic of the T in the T-shape

The Emergency Management T-Shaped Transdisciplinary Model arose from the examination of the T-shaped leadership model, which also applies concepts of breadth and depth. While the use of a single letter-shaped model was appealing from a simplicity perspective, this research explored other shapes, descriptions and formats to determine if this was the most suitable way to represent the research outcomes.

The first consideration was the concepts of breadth and depth that emerged as a key means of categorising the identified human capacities. Examination of numerous 2-dimensional representations of thinking, using graph-type models, dynamic shapes and alphabetic characters was undertaken. In emergency management, other alphabetic models are used and accepted but they were not easily aligned with the outcomes of this study. The research sought an explanatory shape, model or diagram that was instinctively understandable and relatable. The T-shaped model was the model identified that met research aims.

The simplicity of the T-shaped model stands out. Existing T-shaped leadership models have successfully applied the concepts of breadth and depth. Application of the model to the discussion of emergency management is simple and logical. The T-shape shows the 2 key aspects of depth and breadth and allows explanation of the growth of both aspects of the model (i.e. depth and breadth) while retaining an outline of the research outcomes that is easy to understand and share.

The expanding non-static nature of the T-shape

A key aspect of the Emergency Management T-Shaped Transdisciplinary Model is the non-static nature of breadth and depth. When examining the concept of depth, no person enters a role, career or profession knowing all there is to know. Human capacities build and develop over time. The ability to apply human capacities to multiple, dynamic emergency events also builds with experience and developing knowledge. In the role of the Response Manager or Recovery Manager, the individual will commence as a practitioner, undertake training and deliver tasks or outcomes. Over a period, their human capacities build. The outcomes become complicated; experience is built. Applying the T-shaped model, the length of the vertical component grows. The quantum of knowledge, skills and abilities, combined with the experience gained in applying those human capacities, should not go backwards. Thus, the length of the vertical component should not shrink. The final length of the vertical component will never be known. Very few people ever profess to know everything about their role or function. Neither a practitioner nor an academic is likely to reach the end of a learning and experience journey.

The vertical component of the model can be said to be infinite. The vertical component is built from many unique building blocks; each may be a unique human capacity or set of human capacities. A building block could consist of a specific technical skill set or task. The total T-shaped vertical component could consist of many subsets of skills or building blocks. The T-shaped model allows that growth to continue. The only criterion for a building block to be considered part of the vertical component is its applicability to the primary discipline of the individual; that is, their disciplinary skills. A practitioner may develop basic human capacities to do their job and those basic human capacities or skills could form one building block of the vertical component. The practitioner may undertake advanced training and add another block to the vertical component. The practitioner can complete disciplinary leadership or specialisation courses or any number of combinations of human capacities. In each case, the totality of their individual vertical component grows. A breakdown of the vertical component will have some common building blocks for similar practitioners while, at the same time, having a range of unique building blocks.

As a practitioner commences developing the depth of their knowledge (their vertical component), they are likely to start developing the breadth of human capacities (their horizontal component). These components form building blocks. The breadth may arise from the existing human capacities the practitioner brings to their role or from working with other practitioners or other agencies or in other roles at multi-agency emergency events or training exercises. The practitioner may undertake other training with an aim of building breadth of human capacities. The criterion for inclusion of a building block in the horizontal component is skills from other disciplines; that is, transdisciplinary skills or human capacities.

The nature of the continual movement in a practitioner’s development will vary. A person may work initially on components of their vertical development as a practitioner until they reach a level that suits them personally or is required by their organisation (disciplinary human capacities). At this time, the practitioner may become recognised as a Response Manager or Recovery Manager if they have gained the required combination of human capacities and other building blocks in their own unique vertical component of development.

The practitioner’s development across the breadth of skills may be a result of exposure and experience built over time or a deliberate and specific development pathway. The individual may seek to become an Emergency Manager. The person may seek to acquire transdisciplinary knowledge, skills or ability-based human capacities via training, tertiary education, experience or any combination of these. What is unique to everyone is the manner and timing of their vertical (disciplinary) and horizontal (transdisciplinary) development. The Emergency Management T-Shaped Transdisciplinary Model allows for the multiple pathways that may be considered by people in emergency manager, response manager and recovery manager roles.

The outcomes of everyone’s journey through the Emergency Management T-Shaped Transdisciplinary Model is unique to that person. While some aspects will be mandated by an organisation or agency (e.g. completion of basic training in the vertical component), the final shape for each person will be different. The Emergency Management T-Shaped Transdisciplinary Model allows the unique aspects of each role to be demonstrated and shown in a consistent manner. Each person will have an individual and unique blend of vertical and horizontal building blocks that describe their knowledge, skills and abilities—their combined human capacities.

The joining of the horizontal and the vertical

This study identified communication as the human capacity that joins the horizontal and vertical components of the Emergency Management T-Shaped Transdisciplinary Model. This finding reinforces the work of Bierma (2019) who identified that a T-shaped practitioners applied communication skills in the horizontal aspect (p.69) and Augsburg’s (2014) finding that communication was an ‘ideal quality’ of transdisciplinary researchers (p.238). Without communication the vertical and the horizontal aspects are not joined and the model fails. The Emergency Manager with their breadth of human capacities must be able to communicate clearly with personnel during the emergency event as well as with multiple other emergency managers, response managers and recovery managers. The complexity of contemporary emergency and disaster events brings the need for effective communication to the fore. This is reinforced in the human capacities identified in this research.

The need for a new model

Several reasons for the new model have arisen. First, this research identified that emergency management in Australia is not yet a profession. However, those who undertake the roles identified as a Response Manager, Recovery Manager and Emergency Manager are currently traversing a path to professionalisation (Dippy 2020, 2022). The path is not uniformly agreed. While the generic actions required for a recognised profession are described in the literature, the application of those generic actions to the field of emergency management is not settled. The Emergency Management T-Shaped Transdisciplinary Model describes a pathway that supports the progression to professionalisation and it can be debated, agreed and implemented by practitioners, employers, governments and stakeholders to achieve professionalisation. The Emergency Management T-Shaped Transdisciplinary Model provides a foundation for the continuing discourse of professionalisation currently occurring in the sector.

The research identified individual human capacities that emergency managers, response managers and recovery managers require to undertake the respective roles. The human capacities are applied at different levels and times during the total management of the prevention of, preparedness for, response to and recovery from emergencies and disasters. The number of human capacities, exceeding 230, does not allow for them to be easily individually expressed when explaining or developing the roles, functions, training and tasks of the Emergency Manager, Response Manager and Recovery Manager. The theming of each human capacity led to identification of 6 themes for breadth and 8 themes for depth. Continually describing the themes does not support the instant application and understanding of the outcomes of this research to the Emergency Manager, Response Manager and Recovery Manager.

In developing the model, informal discussion occurred with practitioners and academics across Australia and internationally at several conferences and forums. Practitioners and academics ranged from those wishing to enter the field of emergency management to highly experienced practitioners and senior academics. This research found that describing each individual human capacity did not promote an overall understanding of the research outcomes. When describing the outcomes using the T-shaped model, even with its simplest description, an understanding of the research outcomes emerged. Understanding increased by using the themes of depth and breadth or discussing individual human capacities.

The Emergency Management T-Shaped Transdisciplinary Model provides a simple, easily understood starting point for discussions of the human capacities of the Emergency Manager, Response Manager and Recovery Manager. To expect others to start or join the discussions based on a list of over 230 individual human capacities is not likely to engender the level of engagement required to implement these findings in the future. Having emergency managers, response managers and recovery managers as well as employers, government and community stakeholders being able to join the discussion of the human capacities by applying a clear model in picture format should simplify adoption.

Implementation of the Emergency Management T-Shaped Transdisciplinary Model

Implementation of the Emergency Management T-Shaped Transdisciplinary Model requires a range of actions for practitioners and academics. Practitioner engagement will be required to share the model and develop understanding and acceptance in the sector. Academic engagement will include publication of journal articles, national and international conference presentations and ongoing feedback. Engagement with practitioners and academics will allow review, update and refinement of the model. Once stakeholders have reviewed the model, changes can be made across recruitment, selection, training, education and development of practitioners. Training and education packages may need to be modified, selection and recruiting packages may need to be addressed and professional development systems and packages may need to be amended.

Disciplinary skills are developed by vocational training developing skills in the discipline itself. Incorporating the findings of this research in future reviews of the vocational units of competency and qualifications would improve development and depth of skills. Transdisciplinary skills are developed by tertiary education to extend the breadth of skills. This study identified that communication skills are key and communication skills development in vocational and tertiary environments will be required. There is opportunity to update work such as that done by FitzGerald et al. (2017) to produce contemporary standards for tertiary education of emergency managers.

The breadth of skills required is greater than what can be achieved in a tertiary qualification and additional methods to address this gap were identified. Those methods are not included in this paper. An issue that may arise is how to demonstrate that the required depth and breadth of skills acquisition has been achieved. This may be addressed applying an accreditation process that brings together disciplinary skills and abilities (human capacities) as well as transdisciplinary skills and abilities (human capacities). Two international based certification models—those provided by the International Association of Emergency Managers and the International Emergency Management Society—were examined by Dippy (2020). These models could be considered in Australia or an Australian-based model could be developed. The latter would require resources to develop and administer such a certification and ensure it remains fit-for-purpose.

The implementation of the model by practitioners must include consideration of existing professional development activities and programs. While a full implementation model is outside the scope of this paper, examples of activities could include the mapping of existing programs against the model to determine if the professional development activity contributes to the breadth or depth of skills held by an Emergency Manager, Response Manager or Recovery Manager. When the next professional development cycle commences the new activities could be undertaken based on any gaps in previous mappings.

Foreseeable issues and roadblocks

As emergency management is not yet considered a profession, there is no clear path or model implemented to develop people who undertake this important role in the community. This means that implementation of the Emergency Management T-Shaped Transdisciplinary Model will face the same issues and roadblocks as other emerging changes in the field. Issues such as inertia and the lack of understanding of the model may arise. Some practitioners may not continue the path of professionalisation. Some academics may not support the changes to the tertiary education models that will be required. These roadblocks and issues are not unique to this potential model and have been described by Dippy and others when advocating change (Dippy 2025a, 2025b).

The role of champions will be a significant requirement to overcome these issues and roadblocks. Champions can identify potential issues and select appropriate options to address them. Champions can advocate for the model in their respective areas of work. The work of the champions is not separate from, but integral to the ongoing professionalisation of emergency management in Australia.

The identification of issues and overcoming of roadblocks in the implementation of the Emergency Management T-Shaped Transdisciplinary Model is not a separate function from the professionalisation of emergency management. The Emergency Management T-Shaped Transdisciplinary Model can be a catalyst to accelerate the work of professionalisation. The ability to ‘sell’ the model to practitioners, academics, policy makers and the community is key to both implementation of the model and the advancement to professionalisation.

Conclusion

This research establishes a model for the application of the human capacities of the Emergency Manager, Response Manager and Recovery Manager in Australia. The Emergency Management T-Shaped Transdisciplinary Model allows for the description of capabilities required in these defined roles. The development of the model is a contemporary means of describing the roles and functions undertaken by emergency managers, response managers and recovery managers. Proposed development activities supporting the model will require agreement by practitioners and academics and possible changes to vocational and tertiary education offerings. Consideration of the application of an existing certification scheme or development of a specific Australian scheme will support implementation. The Emergency Management T-Shaped Transdisciplinary Model supports professionalisation in Australia by providing a framework for action. The Emergency Management T-Shaped Transdisciplinary Model requires adoption by practitioners, policy makers, academia and the community. The implementation can be undertaken as a series of parallel actions. The implementation actions required are not insurmountable and are within the capacities of emergency management stakeholders, practitioners, policy makers, academics and the community.