Queensland’s exposure to high-risk weather events highlights the need to continuously review emergency communication practices. Between July 2023 and April 2024, Queensland faced 26 extreme weather events, including Tropical Cyclone Kirrily, which struck near Townsville in January 2024. This study assesses the alignment of 12 emergency alerts issued during Tropical Cyclone Kirrily in Queensland in January 2024 with the IDEA model (Internalisation, Distribution, Explanation, Action) and guidelines from the Australian Institute for Disaster Resilience. The alerts were assessed for their alignment with the IDEA model’s elements and the clarity of the recommended actions for affected communities. They were systematically analysed to determine their effectiveness in providing timely and understandable messages, their level of personalisation and if they were disseminated through official channels. The findings revealed that the alerts exhibited deficiencies in the IDEA model's internalisation, explanation and action components.

Introduction

Queensland is regarded as Australia's ‘most disaster-prone state’ (Queensland Fire and Emergency Services 2023, p.19). Human activities and climate change increase the chances of emergencies and disasters as well as related dangers from severe weather events (Sloggy et al. 2021; Kankanamge 2021). Improving risk communication is vital to reduce harm, minimise injury and loss to individuals, and to make communities safer (Ogie et al. 2018; McLean and Ewart 2020).

From July 2023 to April 2024, Queensland experienced 26 extreme weather events including floods, bushfires, cyclones and their associated effects (Queensland Disaster Management Committee 2024). On 17 January 2024, Tropical Cyclone Kirrily developed in the Coral Sea. The cyclone reached its peak as a Category 3 system before making landfall roughly 50 km northwest of Townsville as a Category 2 cyclone on the evening of 25 January. The cyclone brought intense rainfall, caused extensive flooding, damaged infrastructure and resulted in power outages that affected 41 local government areas (Australian Associated Press 2024; Gurtner and King 2024; Queensland Disaster Management Committee 2024).

This study evaluates whether the emergency alerts issued from 24 to 26 January 2024 incorporated the essential principles of effective risk communication. To investigate this, the study used the IDEA model (Internalisation, Distribution, Explanation, Action) as described by Sellnow et al. (2017) to analyse the alerts. The IDEA model was chosen for its effectiveness in evaluating crisis messages that require clarity, relevance and actionable guidance. The analysis is informed by risk communication literature and the emergency alert guidelines established by the Australian Institute for Disaster Resilience (AIDR) (AIDR 2021a; 2021b; 2021c). This research is particularly important for communities that are exposed to high-risk weather hazards. This study aimed to identify issues in the communication approaches used during these events. Improved risk communication enables people to make informed decisions and take appropriate actions for their protection (Sellnow et al. 2017; Sellnow-Richmond et al. 2018). This can reduce the potential for loss of life and property-related damage (Coombs 2018). The need for better risk communication is highlighted by the growing cultural diversity of communities in Australia (Ogie et al. 2018; Bromhead 2023) that have different levels of English proficiency (AIDR 2021a) and the influx of people to Queensland from interstate and overseas who may be unfamiliar with the locality’s exposure to extreme weather (ABS 2021a; ABS 2024).

Literature review

Risk communication and the IDEA model

Communicators often face the challenge of advising at-risk individuals on the best self-protective actions to take during emergencies and crises (Coombs 2009; Sellnow-Richmond et al. 2018; Grantham 2023). Communicating risk is often met with societal or cognitive resistance, which can hinder the acceptance of the risks presented (Covello 2006). Over decades of scholarship, a clear pattern has emerged in the elements that shape risk communication. Several scholars emphasise message framing (Fischhoff 2017; Pidgeon 2021), timeliness (Balog-way et al. 2020; AIDR 2021a), source credibility (Mehta et al. 2017), risk perception (Ulmer et al. 2010; Slovic and Weber 2013) and 2-way public engagement (Balog-way et al. 2020; Lazarus 2024). However, effective risk communication is not limited to the dissemination of information (Coombs 2009) because receivers need to base their decisions on factual and instructional indications (Sellnow et al. 2017; Sellnow-Richmond et al. 2018). Literature on disaster warnings emphasises such a need. Individuals are unaware of what constitutes appropriate action during emergencies (Sellnow et al. 2017). Similarly, poorly framed and equivocal messages decrease risk communication effectiveness and undermine the source’s credibility (Sellnow et al. 2017; Mehta et al. 2017; Lazarus 2024). Including instructions about appropriate actions during emergencies increases the effectiveness of communication as it empowers individuals to prioritise their personal safety (Sellnow et al. 2017). Despite this, an information-only approach is often adopted by communicators who may focus on providing scientific information about the risk or the number of people affected (Sellnow et al. 2017). Slovic (2010) suggests this approach decreases the effectiveness of the intended message. Although information is essential, relying solely on it is insufficient if communicators need to prompt action-taking from individuals (Sellnow et al. 2017). Sellnow and Sellnow’s (2013) IDEA model encapsulates the above by offering a clear and effective framework for emergency alert creation (Sellnow et al. 2017; Sellnow-Richmond et al. 2018). The IDEA model is structured in 4 components of internalisation, distribution, explanation and action.

Internalisation aims to gain the audience’s attention by explaining the significance of the imminent risk to current circumstances. This component has 3 elements of proximity, timeliness and personalisation. Proximity is when the message includes the geographical location of the risk and its effects on the audience. Timeliness includes the urgency of taking immediate action, conveying how imminent the risk may be. Personalisation specifies that the message must address the audience directly, detailing how the risk could personally affect them and those they care about. It must also use a language that resonates with the audience. Internalisation seeks to answer the question: ‘How am I and those I care about affected (or potentially affected) and to what degree?’ (Sellnow et al. 2017, p.555).

Distribution involves selecting communication channels that aim to make the message accessible to all segments of the affected population. Communicators should consider the audience's diversity and use the most appropriate and varied media to disseminate the message. ‘Effective risk communicators must thoughtfully choose the media through which to share our messages to reach all segments of an at-risk population’ (Sellnow and Sellnow 2013, p.3).

Explanation aims to provide a clear and straightforward account of the unfolding events in an easily presented and accessible way. Messages should be concise and free from scientific jargon, making them understandable to a broad and diverse audience. The explanations are issued by credible sources (experts, doctors, authorities) and include internalisation elements with an emphasis on personalisation (Sellnow and Sellnow 2013). This component aims to answer the question: ‘What is happening, why and what are officials doing in response to it?’ (Sellnow et al. 2017, pp.555–556).

Action indicates that when audience members comprehend the risk event and recognise its relevance to them, they seek guidance on how to minimise their personal risk (Sellnow and Sellnow, 2013). The message at this point needs to provide them with specific options and clear instructions to mitigate the risk. This component aims to answer the question: ‘What specific actions should I and those I care about take (or not take) for self-protection?’ (Sellnow et al. 2017, p.556).

Literacy and social capital

Social capital is acknowledged as it is vital to understand and enhance community resilience. The concept of social capital refers to the exchange of information and the building of trust, relationships and values among individuals, groups, families and communities within a network for mutual benefit (Putnam 1994; McLean and Ewart 2020). Unlike physical capital (tools), human capital (skills and expertise) or economic capital (money), which can be tangible, concrete and often owned by individuals or communities, social capital is generated by the established bonds among people and exists abstractly (Coleman 1987; McLean and Ewart 2020; Behera 2023). The essence of social capital lies in the connections within a person’s network that can be relied on during emergencies. Having a strong social network with other individuals in a community, local emergency services organisations or volunteers is considered crucial for individuals to be better placed during emergencies (McLean and Ewart 2020). Disaster literacy is an individual's capacity to interpret information to make informed decisions about mitigation, preparedness, response and recovery (Genc et al. 2022). It also involves adhering to instructions and choosing the best self-protecting actions to take (Genc et al. 2022). According to AIDR (2021a), 44% of people in Australia experience difficulties with numeracy and literacy in English (p.18). A significant portion of the population (30%) is at a level comparable to Year 7 to Year 10 education, and a further 38% are at a level equivalent to Years 11 and 12 (Equity Economics 2022; ABS 2013). Nearly 23% of the population uses a language other than English at home. This speaks to Australia’s linguistic diversity, with more than 300 languages spoken in the country (ABS 2022). Consequently, ineffective or overly complex messages can deter individuals from making the best decisions during emergencies and severe weather events (Ogie et al. 2018; Grantham 2023). Therefore, considering Australia's demographics, cultural composition and language proficiency, effective communication during emergencies is crucial for policymakers and emergency services to minimise harm and damage to at-risk individuals and communities (Teo et al. 2019; McLean and Ewart 2020; Grantham 2023).

Method

The analysis of emergency alerts involved examining a dataset consisting of 12 alerts collected from the live dashboards as they were published by local government councils. This included 4 alerts on 24 January, 6 alerts on 25 January and 2 alerts on 26 January (Table 1). The focus was to identify whether the warnings satisfied the components of the IDEA model, particularly in terms of timeliness, message framing and personalisation as supported by the AIDR guidelines (AIDR 2021a; 2021b; 2021c) and risk communication literature.

The IDEA model definitions were drawn up as a codesheet. Using 2 researchers, 3 alerts were selected for a pilot coding process. This resulted in substantial similarity between the 2 coding outputs. However, there were differences in the interpretation of internalisation and action components. These were discussed, and the codesheet was updated to provide consistency in analysis. The pilot coding returned a Cohen’s Kappa of 0.57, which is classified as moderate agreement. Upon clarification and further coding, the Cohen’s Kappa was increased to 0.89, which is considered almost perfect agreement.

The alerts were analysed based on the 4 components of the model. For internalisation, the definition as outlined by the IDEA model was used, which looks at how the message holds attention by stressing the urgency of the risk. This included elements of proximity and timeliness that were marked as present or not.

Proximity was marked as present when the geographical position of the cyclone was mentioned. Timeliness was marked as present if information regarding the movement of the cyclone was mentioned. The AIDR guidelines (AIDR 2021b) state that effective alerts must address critical details, including ‘where the threat is, when it will occur, who will be affected, how they will be affected, what they can/should do to respond’ (p.6). Personalisation was assessed based on the alert delivering a personable message. This involves using simple, clear language such as ‘shorter, more common words where possible, removing operational language or jargon (e.g. mention a fire truck rather than a fire appliance), using short, to-the-point sentence construction, and keeping instructions brief and specific’ (AIDR 2021b, p.6). This guideline and scholarship made the element of personalisation another measure marked as present or not. If all parts of the internalisation definition were marked, then the alert ‘satisfied’ the element. If one or more elements were missing, then the component was categorised as ‘not fully satisfied’, and if no elements were marked, then the element was ‘not satisfied’. This procedure was replicated for the other components.

Distribution was satisfied if the official channel for issuing the alerts was used, which was identified as issued by the local government councils via their respective dashboards. The analysis of this element was limited to the alert system, rather than the entire distribution network across the government. Therefore, the distribution element was always ‘satisfied’.

The element of explanation was assessed as present if the message was clear and accessible by:

...ordering information so that the most critical information is first, providing instructions in a logical sequence.

(AIDR 2021b, p.6)

We particularly looked for where the alerts used headings to break up text and help people navigate to the information they require.

Finally, the element of action was assessed as satisfied if the message provided clear instructions to people on how ‘to reduce their personal risk’ (Sellnow and Sellnow, 2013, p.3). AIDR guidelines (2021 b, p.9) were used to determine the presence of elements of actions if the message ‘provide targeted and tailored instructions to at-risk community members about what protective action(s) to take and why these protective actions are necessary’, in line with Sellnow and Sellnow (2013) and Sellnow et al. (2017).

These elements are inherently intertwined with not only the IDEA model being the primary framework but also with the AIDR guidelines and research guiding this study. Combining these resources created a structured framework to evaluate the effectiveness of the alerts and to identify elements that may require enhancement.

Five alerts considered for the study, issued on 24 January 2024, were those found in the emergency alerts dashboard on the Queensland Government Disaster Management website. Community members could access these alerts via a link provided in text messages they received from the emergency services. The remaining 7 alerts were messages sent by the Queensland State Disaster Coordination Centre. Data collected was based on what was available to the researcher who was not at the location of the event. Table 1 lists the 12 alerts used in this study.

Based on the selected literature and methodology, this research responds to the following research question: ‘Did emergency alerts issued during TC Kirrily in January 2024 adhere to key foundational elements of risk communication based on the IDEA model?’.

Ethics statement

Ethics approval was not required for this study as the data used was publicly available and no human subjects were involved in the study. However, analysis used work by Gurtner and King (2024) to conceptualise findings. Those authors provided permission to use the research data and findings.

Table 1: Emergency alerts collected and analysed.

| No. | Name | Date and time | Type |

| 1 | Whitsunday Islands | 10 am – Wednesday, 24 January 2024 | Full message |

| 2 | Gumlow, Townsville | 12.15 pm – Wednesday, 24 January, 2024 | Full message |

| 3 | Cungulla, Townsville | 12.15 pm – Wednesday, 24 January, 2024 | Full message |

| 4 | Saunders Beach, Townsville | 12.15 pm – Wednesday, 24 January, 2024 | Full message |

| 5 | Burdekin | 12:42 pm – Thursday, 25 January 2024 | Text message |

| 6 | Townsville | 3.51 pm – Thursday, 25 January 2024 | Text message |

| 7 | Whitsundays (Bowen and surrounds) | 4.15 pm – Thursday, 25 January 2024 | Text message |

| 8 | Hinchinbrook | 5.22 pm – Thursday, 25 January 2024 | Text message |

| 9 | Burdekin | 6.20 pm – Thursday, 25 January 2024 | Text message |

| 10 | Townsville | 9.09 pm – Thursday, 25 January 2024 | Text message |

| 11 | Townsville | 6 am – Friday, 26 January 2024 | Full message |

| 12 | Townsville | 8:27 am – Friday, 26 January 2024 | Text message |

Source: Queensland Government Disaster Management at www.disaster.qld.gov.au/disaster-management-portal.

Data analysis

Overview of findings

Table 2 summarises the analysis of the 12 emergency alerts and shows that only one alert fully satisfied the element of internalisation. The majority (11 alerts) failed to fully personalise or make the information relatable to the audience. When examining the element of distribution, all 12 alerts were issued by official channels, thus satisfying this component. The explanation component reveals that 6 of 12 alerts provided clear and understandable information. However, 6 alerts did not fully meet this standard in terms of explaining how the situation developed and in making the message personable.

For the action component, only one alert (Townsville 9.09 pm) satisfied the specific and actionable instructions requirement. The remaining 11 alerts did not meet this standard. This is a significant area for improvement.

Findings

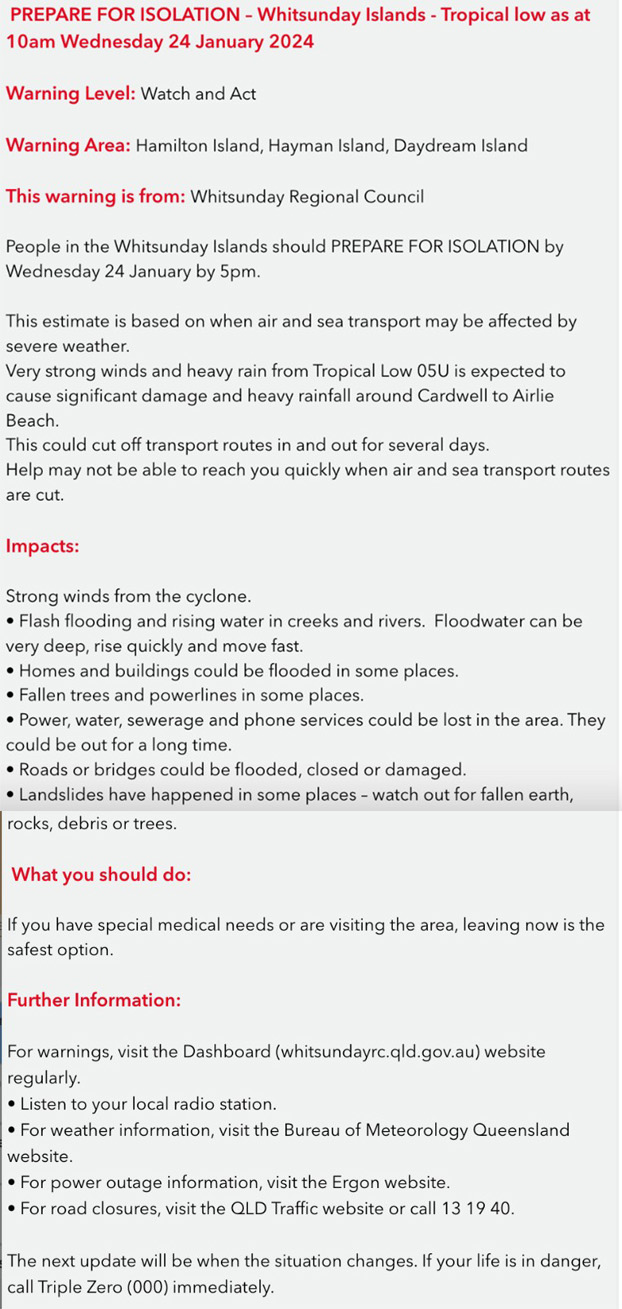

Drawing from Table 2, the first alert analysed was issued by the Whitsunday Regional Council on 24 January (Figure 1). The explanation and distribution components were satisfied, given the message stated the development of the event and it was issued via the official local council dashboard. The internalisation and action components were not fully satisfied as the personalisation element was lacking and specific actions were omitted. This alert states, ‘If you have medical needs or are visiting the area, leaving now is the safest option’. It seems to not be specific to the local population as it lacks options on where people can go and does not provide precise actions to take apart from ‘prepare for isolation’ or ‘listen to the radio’ and ‘visit the dashboard website’. Similar conditions were found in the next 3 alerts issued by the Townsville Local Disaster Management Group for the local government areas of Gumlow, Cungulla and Saunders Beach.

Table 2: Emergency alerts collected and analysed.

| Alerts | Internalisation | Distribution | Explanation | Action |

| 1) Whitsunday Islands, 10 am, Wednesday 24 January 2024 (full message) |

Not fully satisfied | Satisfied | Satisfied | Not fully satisfied |

| 1) Whitsunday Islands, 10 am, Wednesday 24 January 2024 (full message) |

Not fully satisfied | Satisfied | Satisfied | Not fully satisfied |

| 3) Cungulla, Townsville, 12.15 pm, Wednesday 24 January 2024 (full message) | Not fully satisfied | Satisfied | Satisfied | Not fully satisfied |

| 4) Saunders Beach, Townsville, 12:15 pm, Wednesday 24 January 2024 (Full message) | Not fully satisfied | Satisfied | Satisfied | Not fully satisfied |

| 5) Burdekin, 12:50 pm, Thursday 25 January 2024 (text message) | Not fully satisfied | Satisfied | Not fully satisfied | Not satisfied |

| 6) Townsville, 3:51 pm, Thursday, 25 January 2024 (text message) | Not fully satisfied | Satisfied | Not fully satisfied | Not satisfied |

| 7) Whitsundays, Bowen and surroundings, 4.15 pm, Thursday 25 January 2024 (text message) |

Not fully satisfied | Satisfied | Not fully satisfied | Not satisfied |

| 8) Hinchinbrook, 5.22 pm, Thursday 25 January 2024 (text message) |

Not fully satisfied | Satisfied | Not fully satisfied | Not fully satisfied |

| 9) Burdekin 6.20 pm, Thursday 25 January 2024 (text message) | Not fully satisfied | Satisfied | Not fully satisfied | Not satisfied |

| 10) Townsville, 9.09 pm, Thursday 25 January 2024 (text message) cyclone crossing | Not fully satisfied | Satisfied | Satisfied | Satisfied |

| 11) Townsville, 6 am, Friday 26 January 2024 (text message) | Not fully satisfied | Satisfied | Satisfied | Not fully satisfied |

| 12) Townsville, 8:27 am, Friday 26 January 2024 (Text message) | Not fully satisfied | Satisfied | Not fully satisfied | Not fully satisfied |

Source: Queensland Government Disaster Management at www.disaster.qld.gov.au/disaster-management-portal.

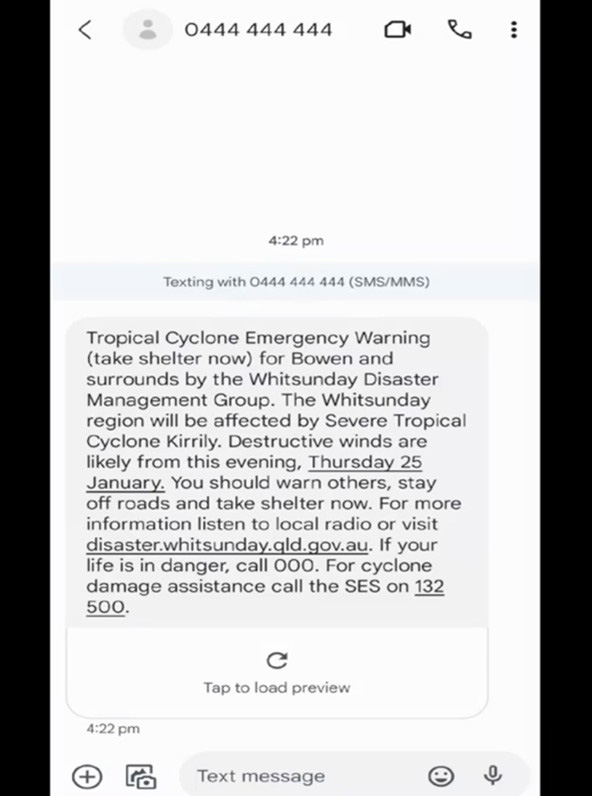

Explanation and distribution were satisfied in these instances, but internalisation and action lacked personalised messages and omitted specific actions to follow. These 3 alerts advised people to ‘decide now where you will go’ and ‘prepare your home’, which are general instructions. They also emphasise specific actions such as ‘block toilets, sinks and drains with sandbags’ or ‘empty and turn off fridges and freezers’. Evacuation procedures and evacuation centres or shelters are indicated in the lower section of the message. Although being issued by different disaster management groups, 5 of the 6 alerts issued on 25 January (the day the cyclone made landfall) presented a similar approach (Figure 2). In this instance, the alerts were text messages sent by the Queensland State Disaster Coordination Centre via the number 0444 444 444. For these alerts, the elements of internalisation, explanation and action were not fully satisfied and distribution was satisfied. The alert for Whitsundays (Bowen and Surrounds), as appeared on mobile phones (Figure 2), includes general instructions like ‘warn others, stay off roads and take shelter now’, which were analysed as not specific enough. The alert for Whitsunday Islands at 10 am on 24 January includes ‘leaving now is the safest option’, while a more direct message could be, ‘make arrangements to stay with family or friends away from the affected areas immediately’. This lack of personalisation and specific actions is consistent across the alerts related to Burdekin (x2), Townsville, Whitsundays (Bowen and Surrounds) and Hinchinbrook.

The alert issued for Hinchinbrook at 17:22 pm on 25 January was the only text message alert that mentioned evacuation centres. The alert issued at 9.09 pm on 25 January 2024 satisfied all the components. The alert warns of the risk associated with the cyclone's eye and adds that Tropical Cyclone Kirrily was making landfall, stressing the importance for people to stay sheltered unless advised otherwise.

It said:

Severe Tropical Cyclone Kirrily is currently crossing the coast as a Category 3. Shelter in place and stay indoors until advised. Winds could stop suddenly if the eye of the cyclone goes over your area. Very dangerous winds could start again quickly.

The last 2 alerts analysed were issued by Townsville Disaster Management Group on 26 January, the day after Tropical Cyclone Kirrily made landfall; one at 6 am and one at 8:27 am. The first alert indicated that the threat had passed and it was safe for people to leave their place of shelter. This message also advised people to be aware of fallen powerlines but did not instruct them on what to do if they encountered one. While distribution and explanation were satisfied, internalisation and action were not fully satisfied as the message could have included specific information and instructions about the most compelling hazards people could encounter and how to deal with them. The second message addresses residents directly and advises them to conserve water due to power outages. Lastly, the message explains why residents need to conserve water, but it does not provide an explanation of what was being done to restore access to water nor provides information on how long it is going to take to restore services.

Figure 1. Emergency alert (full message) for Whitsunday Islands, 10 am on 24 January 2024.

Discussion

To make meaningful interpretations of the data, it is essential to associate the findings with the perspectives of people who have experienced the emergency firsthand. For this reason, while the following examples taken from trending social media applications are not part of the formal dataset used for analysis, their inclusion in the discussion serves a supplementary role. These examples were selected to provide real-world illustrations that contextualise the findings and offer practical relevance.

Figure 2. Emergency alert (text message) for Whitsundays, Bowen and surroundings on 25 January 2024.

TikTok has become an important platform for authorities and communities to share, get information and organise during emergencies (Lewis and Grantham 2022; Stolero et al. 2024). Further examples are drawn from a survey following Tropical Cyclone Jasper in December 2023 and Tropical Cyclone Kirrily in January 2024 (Gurtner and King 2024). These examples demonstrate the broader applicability of the theoretical framework, allowing for a rich discussion of the data. Gurtner and King’s (2024) survey received 267 responses (209 Tropical Cyclone Kirrily, 58 Tropical Cyclone Jasper) from people who experienced these events. The findings shed light on the need to improve communication, particularly related to warnings and evacuation (Gurtner and King 2024). An emergency alert delivering the intended internalisation element remains central to high effectiveness. Emphasising the proximity of the risk and the importance of timeliness increases the perceived personal effect (personalisation) of the risk by the receiver. Only the alert issued for Townsville at 21:09 came close to satisfying the components.

A common challenge for emergency communicators is getting the audience to internalise messages about risks when the effects are not immediately apparent (Sellnow and Sellnow 2013). Although social media was not analysed in this study, it was observed that many Townsville residents used these platforms to express their concerns (Grantham 2025). For example, one TikTok video showed a woman at home with her child who commented about the unclear messages related to the expected landfall. This video has been removed from the platform, but the dynamics show the importance of emergency alerts, clearly conveying the proximity and relevance of the impending risk to the intended audience, as well as when they can expect it to affect them (Grantham 2025).

Gurtner and King (2024) reported that inaccurate and/or conflicting information could lead to complacency when similar alerts are issued in future events, affecting the risk perception and decreasing the overall effectiveness of the intended messages. Framing messages properly is also critical for effective alerts, as different people interpret the same indication differently (Fischhoff 2017). One of the respondents in Gurtner and King (2024) commented that the map that tracked Tropical Cyclone Kirrily led some people to panic when they saw the forecasted cyclone crossing line in their area. It also caused complacency for other people outside of the area. Crafting messages that indicate the best self-protective actions to take remains a challenge for communicators (Coombs 2009; Sellnow-Richmond et al. 2018) and is in line with this study’s findings related to shortcomings in the explanation and action components. Gurtner and King (2024) also reported that people complained and suggested improvements concerning ‘communication and information, especially in areas of warnings and evacuation’ (p.31). Some respondents stated that warnings started too early and information was given too early or too late. This diluted the warning effectiveness. This also suggests that the alerts leading up to Tropical Cyclone Kirrily’s landfall needed to be timed better despite satisfying the timeliness element of the internalisation component. This example shows the need for alerts to be personalised to the intended audience and is supported by research by Lazarus (2024), Mehta et al. (2017) and Sellnow et al. (2017) about the risk of alerts losing their credibility if not issued in a timely and clear manner with an action-prompting effect.

While the IDEA model provides a good framework to construct emergency messages, meeting the timeliness criterion does not necessarily guarantee that alerts will be issued at the appropriate time. In other words, although the IDEA model promotes the importance of timeliness, it does not inherently ensure that alerts will align with the critical timing required by the affected population. Timeliness is a feature of a message being personable. Another example of the importance of well-crafted alerts can be drawn from an Irish backpacker on her working holiday visa in Townsville expressing her concerns via her TikTok account about not knowing the actions and preparedness steps to take. This video was viewed and used as a practical example of real-world dynamics occurring. In the literature, disaster literacy is directly linked to the level of social capital people enjoy (McLean and Ewart 2020). Although emergency services organisations and Townsville Disaster Management Group sent text alerts, the lack of literacy and the relatively limited social capital of recently arrived migrants and travellers can hinder their understanding of the best self-protective actions to take (Teo et al. 2018; McLean and Ewart 2020).

Gurtner and King (2024) reported that family and friends were among the most important sources of information during Tropical Cyclone Kirrily. The nature of backpackers being away from their families and friends suggests they cannot rely on this network for information. Additionally, it is important that backpackers and tourists may move independently or be part of a group, potentially exacerbating their circumstances. What dynamics might have occurred if non-English speakers were present instead of an Irish national? And where can people with low social capital get this information if the official communications exclude this? In light of these questions, it is important that alerts consider the factors of potentially limited social capital. Queensland experienced significant migration and immigration and has increased its population by 2.64% in 2023, which equates to 140,426 people (ABS 2021a; ABS 2024; iD Community N/D). In particular, official data from the ABS (2021b; City of Townsville 2021) shows that in 2021, 14% of Townsville’s population was born overseas and 39% of Townsville's overseas-born residents use a language other than English. This indicates that newcomers may not possess the same English literacy level and experience as locals.

Teo et al. (2019), Zahnow et al. (2019), AIDR (2021a) and Bromhead (2023) indicate that language barriers as well as limited social capital for overseas and interstate migrants increase a person’s vulnerability during disasters. While the importance of well-crafted emergency alerts is pivotal to trigger the action-prompting effect desired, warnings rely on the audience's ability to understand and interpret the messages (Bartolucci et al. 2023). This emphasises the relevance of the internalisation component and the AIDR guidelines (AIDR 2021a) about delivering messages in a language that audiences can understand. The only alert satisfying internalisation was the alert issued at 21:09 on 25 January by Townsville because the function of this alert was to advise of Tropical Cyclone Kirrily conditions, which at that stage was crossing the coastline. There was nothing left to instruct or suggest because people had to stay in their place of shelter and wait for the cyclone to pass.

Analysis of the alerts revealed concerns regarding the brevity and lack of detailed, action-oriented instructions in the text messages. As the data shows, the text message alerts from Burdekin (x2), Townsville, Whitsundays (Bowen and surroundings) and Hinchinbrook, apart from indicating to ‘warn others, stay off roads and take shelter now’, did not provide specific actions to take unless people clicked on the link provided. By accessing the full messages of the alerts, people were provided with detailed guidance on actions to take. However, as seen in the alerts from Whitsunday Islands, Gumlow, Cungulla, Saunders Beach and Townsville (x2), their effectiveness is questionable when considering the cognitive and emotional state of recipients. People experiencing stress, panic or fear often struggle to absorb detailed or lengthy information. Additionally, the AIDR guidelines suggest that ‘community members may be reluctant to click on links received via text messages or emails for fear of scams’ (AIDR 2021b, p.11). During such demanding moments, directing people to take additional steps could make communication less effective (Lazarus 2024). When an emergency requires a prompt response, people need clear, actionable instructions directly within the message. Sellnow et al. (2017) suggest it is unreasonable to make people navigate additional steps or click-throughs, resulting in delayed or improper actions. The post-cyclone Townsville alert issued at 6 am on 26 January does not provide specific instructions about what to do when encountering fallen powerlines, apart from advising people to call the authorities. Furthermore, since this was a full message rather than a text message, it raises questions about whether other ‘full message’ alerts provide the necessary instructions. Therefore, to answer the research question, this analysis showed that the alerts could have benefited from a close alignment to the IDEA model components, particularly Internalisation, Explanation and Action. This suggests that failure to satisfy such components is related to the messages not being personable and that the accuracy of the alerts is contingent on how close the threat is to the community. It is possible to observe this given that the final 3 alerts, one when the cyclone was crossing the area and 2 when it had passed, satisfied all the components, although with a few considerations. Based on the IDEA model, distribution was satisfied given that the alerts provided external links, such as the local disaster dashboard, the Bureau of Meteorology website or Queensland Fire and Emergency Services website, as well as encouraged people to listen to the local radio for updates, and they were issued and available for perusal via a trustworthy and consistent channel.

Conclusions

This study examined the effectiveness of emergency alerts issued during Tropical Cyclone Kirrily in Queensland. Through applying the IDEA model, this research provides insights into ways to improve the effectiveness of emergency alerts. The analysis of the alerts based on the IDEA model revealed that while these messages successfully distributed information through trusted channels, they often lacked the necessary personalisation and actionable guidance to motivate the public to take appropriate protective measures. The findings demonstrate that most alerts failed to fully internalise the risk for the intended audience, potentially leading to confusion and uncertainty.

The study did not specifically consider the unique communication methods and cultural nuances of local Indigenous communities, such as the people of Palm Island who were affected by Tropical Cyclone Kirrily. Indigenous cultures have distinct communication styles and channels that differ from mainstream approaches. This aspect could be the focus of future research requiring face-to-face interviews to gather important insights into risk communication effectiveness within these communities.

While the study acknowledged the importance of 2-way communication, community engagement and risk perception, it did not incorporate these aspects into the research methodology. This decision was influenced by logistical constraints, including the need for ethical approval to conduct interviews to gather firsthand perspectives from community members.

This study incorporated TikTok examples to offer practical examples of the dynamics that occur using real anecdotes to illustrate concepts. These examples bring attention to the role of limited social capital and disaster literacy among tourists, effectively corroborating the analysis. However, given that this serves as an example only, it was not formally analysed.

Finally, it is acknowledged that other models or theories could have been used to develop this study. Future research could apply such models to investigate similar problems through different lenses.