Cyclone Gabrielle struck Aotearoa New Zealand in February 2023 and was one of the most devastating disaster events in the country’s recent history. Response efforts involved a wide range of stakeholders and exposed critical coordination challenges. This study examined the effectiveness of these responses through 15 semi-structured interviews with representatives from national and local emergency management agencies, non-government organisations and community groups, as well as marae [meeting place] leaders involved in the response. It focused on the coordination among these different actors to identify strengths, gaps and challenges, and to understand the implications for disaster resilience. Findings reveal systemic issues in communication and coordination that hindered timely and equitable response, particularly in reaching people in rural areas, collaborating with Māori communities and engaging volunteers. Cultural disconnects, under-utilisation of local networks and training gaps for surge staff and emergency personnel also limited response effectiveness. The study highlights the need to strengthen pre-disaster relationships with iwi [tribes], marae and community-based groups to enhance workforce preparedness and embed culturally responsive practices.

Introduction

The increasing frequency and intensity of extreme weather events, combined with population growth, inadequate urban planning and rising social and economic inequalities, present significant global challenges. As a result, disaster risk reduction and management (DRRM) has become essential for global and national governance (Akter and Wamba 2019). There is a growing recognition of the role played by DRRM actors in supporting affected people during emergencies and disasters. Response efforts are expected to be rapid, contextually appropriate and align with the priorities of those affected while also catering to local coping mechanisms (Nyahunda et al. 2022). Effective collaboration among stakeholders including government agencies, international organisations, non-government organisations and local communities is crucial to maximise resources and deliver coordinated actions. Such cooperation helps prevent duplication of effort and should reduce the burden on affected people during a crisis (Akter and Wamba 2019; Rawsthorne et al. 2023). Cyclone Gabrielle formed in the Coral Sea in early 2023 and made landfall in Aotearoa New Zealand over 12 to 16 February. The cyclone had devastating consequences for the Hawke’s Bay and Tairāwhiti regions as it brought intense rainfall, 10-minute sustained wind speeds of up to 150 km/h and widespread flooding and landslides. These extreme conditions significantly affected lives, livelihoods and local infrastructure. At the height of the cyclone, approximately 225,000 households experienced power outages and thousands of people were forced to evacuate due to rising floodwaters. Sadly, 11 lives were lost and more than 10,000 people were displaced from their homes. The cyclone caused extensive damage to critical infrastructure along the east coast of the North Island including roads, power lines, water systems and telecommunications networks (MFAT 2023). The total cost of the destruction was estimated at NZ$14.5 billion (New Zealand Government 2023). Cyclone Gabrielle ranks as the second costliest recorded hazard-related disaster in Aotearoa New Zealand; second only to the Christchurch earthquakes in 2011 (Sowden 2023).

For the third time in its history, a State of National Emergency was declared in Aotearoa New Zealand. The New Zealand Government received international assistance from countries such as Australia, Fiji, the United Kingdom and the United States. In the most severely affected regions of Hawke’s Bay and Tairāwhiti, more than 50 organisations participated in the response. However, the scale of the disaster posed significant challenges for the emergency management sector leading to criticisms regarding delays and the appropriateness of the response (Bush 2023). Several months after Cyclone Gabrielle, media narratives framed the event as a ‘wake-up call’, emphasising the urgent need for greater attention to extreme weather risks and their management (Goode 2025).

This study examined the response efforts implemented during Cyclone Gabrielle in the Hawke’s Bay region with a particular focus on coordination and effectiveness. The research aimed to identify best practices, challenges and gaps as well as opportunities to improve response.

Disasters and response efforts: an overview

Disasters are characterised by their economic, human, physical and environmental impacts on communities. People’s experiences of emergencies and disasters can differ widely depending on their economic situation, social networks, access to external resources, belief systems as well as their past disaster knowledge (Appleby-Arnold et al. 2021). They may have highly diverse expectations of external aid agencies, priorities for response and recovery and may develop very different coping mechanisms. It is, therefore, critical that resources are mobilised and actions are conducted in contextually relevant ways that consider the social, cultural and economic aspects that characterise local communities (Graveline et al. 2024: Versaillot and Honda 2024).

Emergency and disaster response should be informed by proper assessments of the effects and needs of communities on the ground (Sarabia et al. 2020). People and community-based organisations are often the first to respond since they live in the areas affected, are familiar with the local geography and are cognisant of the local norms and available resources (Quarantelli 1988). For example, during the 2010 Haiti earthquake, local communities including neighbourhood committees, volunteers, faith-based organisations and community health workers mobilised to help their fellow citizens with rescue efforts, food, water and shelter (Kay and Johnson 2012). These groups leveraged existing networks to coordinate relief efforts, provide emotional support and offer shelter to people affected (Smith and Williams 2013).

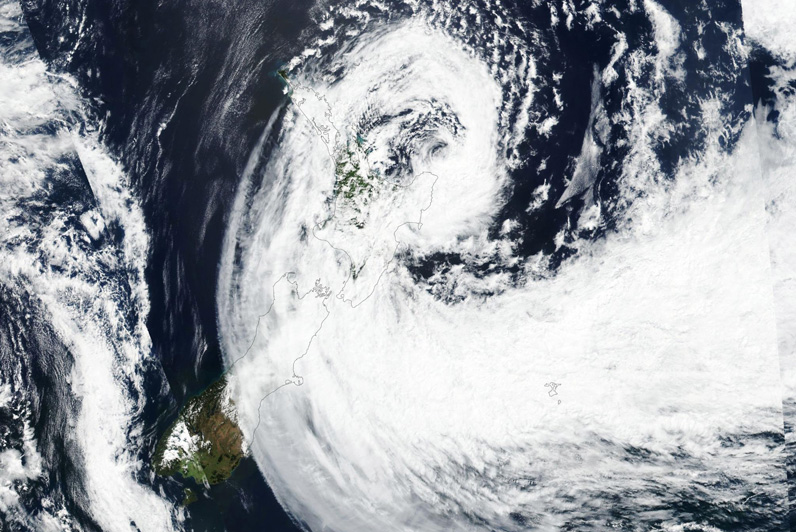

Satellite imagery of Cyclone Gabrielle approaching Aotearoa New Zealand, 9 February 2023.

Image: NASA Worldview, public domain (https://worldview.earthdata.nasa.gov/), photo by Lauren Dauphin, 14 February 2023.

Policymakers, practitioners and scholars widely recognise the importance of integrating community organisations and volunteer groups into disaster response efforts (Skar et al. 2016; Kristian and Fajar Ikhsan 2024). The Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030 (UNDRR 2015) underscores the value of citizen participation in disaster risk management. In Aotearoa New Zealand, the National Disaster Resilience Strategy (MCDEM 2019a) emphasises that emergency response should ‘enable and empower community-level response, and ensure it is connected into wider coordinated responses, when and where necessary’ and specifically calls for ‘building the relationship between emergency management organisations and iwi/groups representing Māori, to ensure greater recognition, understanding, and integration of iwi/Māori perspectives and tikanga in emergency management’ (MCDEM 2019c, p.3). However, in practice, top-down approaches often prevail, overlooking local knowledge and established community networks. Scholars and practitioners frequently highlight coordination challenges when emergency management organisations operate according to legislation, procedures and codes of conduct that may conflict with the informal structures of local communities (Grant and Langer 2019; Haynes et al. 2020). Research emphasises the importance of pre-disaster preparedness and strong inter-organisational relationships to enhance response effectiveness (Le Dé et al. 2024).

Ongoing challenges in coordination among response stakeholders, compounded by a lack of collaboration and competition for limited information and funding, often result in inefficiencies, resource misallocation, service gaps and even chaotic response efforts (Steets and Meier 2012; McLennan et al. 2016). For example, following the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami and the 2010 Haiti earthquake, numerous organisations deployed personnel and resources simultaneously, but without effective coordination, resulting in operational overlap and inefficiencies (Parkash 2015). Similar challenges were observed during the 2011 Christchurch earthquakes, underscoring the need for enhanced coordination within Aotearoa New Zealand’s disaster response framework (Bourk and Holland 2014; Burke 2018). Insufficient collaboration among stakeholders can result in overlapping aid distribution, inefficient resource allocation and unmet needs among affected populations.

Since the late 1990s, various tools and mechanisms have been introduced to improve coordination, such as the Sphere Standards (Sphere Association 2000) and the UN Cluster Approach, first introduced by the Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC 2005) and later detailed in the UNHCR Emergency Handbook (UNHCR 2023). These frameworks are designed to enhance response to humanitarian crises, for example, initiatives that improve inter-agency learning have resulted in the Active Learning Network for Accountability and Performance in Humanitarian Action networks in 1997 (Brown and Donini 2014). The Sphere Standards provide principles and guidelines for the provision of humanitarian assistance and aim to enhance humanitarian responses while holding organisations accountable for their actions. The United Nations Office General Assembly resolution (UNOCHA 1998) emphasises the importance of adhering to humanitarian principles, which include human dignity, impartiality, neutrality and independence. These principles are crucial for effective coordination in times of crisis (Lie 2020). They are geared towards accountability and response ethics and foster trust among affected populations.

The Cluster Approach was developed by the United Nations to enhance cooperation and the exchange of information between different international, national and local organisations operating in the same sector or region (Knox-Clarke and Campbell 2018). At the core of the UN cluster system is the need for coordinated efforts and optimisation of resources and actions in a disaster-affected area. The coordination mechanism has been used by more than 60 countries since its establishment. In Aotearoa New Zealand, the Coordinated Incident Management System (CIMS) is central to coordinating responses during emergencies and disasters. CIMS adapts the Australasian Inter-service Incident Management System© (AIIMS) and the Incident Command System (ICS) from the USA. Such coordination mechanisms have been criticised for not being suitable for coordinating responses required in complex disasters (Buck and Aguirre 2006; Miller et al. 2025). In Aotearoa New Zealand, CIMS serves as the primary framework for managing responses, though critiques persist regarding its accessibility and effectiveness for informal actors such as non-government organisations, community-based organisations, iwi [tribes] and marae (Simo and Bies 2007; Mathias et al. 2022). While formal efforts have been made to increase iwi and marae participation within CIMS structures, their full integration remains in progress and varies considerably across regions.

Critique of Aotearoa New Zealand’s emergency management system has centred on its ability to facilitate inter-organisational collaboration during emergencies. Case studies such as the 2010–11 Christchurch earthquake sequence and the 2017 Port Hills fires revealed challenges in multi-agency coordination, including unclear mandates, strained relationships and inconsistent communication (Phibbs et al. 2012; AFAC 2017; Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet 2018; New Zealand Government 2024). In a review of the all-of-government response to the COVID-19 pandemic (Office of the Auditor-General 2022), difficulties were highlighted in unifying diverse agencies under a coherent operational structure (Ongesa et al. 2025). These issues are often driven by differences in organisational culture, priorities and procedures resulting in fragmented and inefficient responses (Comfort 2007).

Background on the Hawke’s Bay region

The Hawke’s Bay region in the North Island is prone to a variety of hazards such as earthquakes, floods, tsunamis, droughts, bushfires and cyclones. The 1931 Hawke’s Bay earthquake remains the deadliest disaster in New Zealand’s history with a total of 256 fatalities. Most of the population lives on floodplains and, even though extensive flood control works have taken place, flooding remains a significant risk (East Coast LAB 2018). Landslides threaten transport networks and economic productivity (e.g. wineries, orchards, tourism). People living in coastal areas experience land erosion, tsunamis, flooding and sea-level rise. Climate change is expected to cause more frequent and intense extreme weather events in this region.

According to the 2023 Census, the Hawke’s Bay region had a population of 175,074 with 64,695 residents in Napier and 85,965 in Hastings (Stats NZ 2024a; Stats NZ 2024b). Māori make up approximately 30% of the population (Stats NZ 2024a). The region has high levels of socio-economic deprivation and a large number of residents live in areas classified within the most deprived deciles of the New Zealand Deprivation Index (NZDep 2023)1 (Atkinson et al. 2024). These characteristics have important implications for emergency planning and response. Given the region’s extensive rural landscape and dispersed population, marae have become essential community-led hubs for response and recovery as they afford culturally grounded and trusted spaces rooted in tikanga Māori [Māori customary practices] and the principles of manaakitanga [hospitality and care] (Hawke’s Bay Civil Defence Emergency Management Group 2024).

Aerial view of flood damage and sediment deposition along the Tūtaekurī River, Hawke’s Bay region, February 2023.

Image: Todd Miller

During emergencies, marae frequently operate as evacuation centres or welfare hubs offering shelter, information and support to individuals and whānau [family]. Because marae occupy a central position within both Māori and wider communities, marae leaders and whānau are able to rapidly mobilise resources facilitate local coordination and act as conduits to distribute essential supplies. This underscores the importance of marae not only as logistical hubs but also as culturally embedded institutions that foster community cohesion, leadership and wellbeing in times of crisis (Kenney and Phibbs 2015). A study conducted with Māori communities in the Hawke’s Bay region highlighted the significance of marae in disaster contexts and emphasised that concepts such as Aroha ki te Tangata [the capacity to provide support within the community] and Manaakitanga are central to the Māori conceptualisation of resilience (Le Dé et al. 2021; Laking et al. 2024).

Method

Careful consideration was given to the methodological design to minimise the burden on affected communities while ensuring the collection of valuable insights. Given the presence of multiple disaster agencies and an overwhelmed local populations, ethical concerns regarding participant wellbeing were prioritised (Gaillard and Peek 2019; Beavan 2023). A decision was made to interview key informants from organisations involved in disaster response rather than local community members so as to not add extra pressure and avoid research fatigue.

The recruitment process included key informants from central and local government agencies, non-government organisations and marae who were identified using purposive sampling and existing professional networks. Participants were selected for their direct involvement in the Cyclone Gabrielle response to provide a comprehensive understanding of the response efforts.

There was an attempt to capture a wide range of perspectives by interviewing participants operating at different scales and representing organisations with diverse roles. The number of interviews was determined based on the principle of data saturation, where additional interviews are unlikely to yield new insights. Interviewees expressed their own opinions and did not speak on behalf of their organisation. This distinction was made clear in the ethics documents provided to interviewees and was emphasised before each interview.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 15 key informants:

- 3 from central government agencies

- 4 from local government agencies

- 2 from non-government organisations

- 3 from community-based organisations (marae)

- 3 from emergency services organisations.

The interviews were conducted in person and online between December 2023 and February 2024. Each interview lasted between 30 and 70 minutes depending on the participant’s availability and flow of the interview. The semi-structured format enabled participants to share their views and allowed for general themes to be explored such as inter-agency collaboration, response being socio-culturally adapted and rural response capacity including challenges, gaps and opportunities.

Data analysis followed an inductive thematic approach and was guided by Braun and Clarke’s (2006) 6-step framework. Transcripts were coded to identify themes that emerged from the study. To provide credibility, data triangulation was employed and interview findings were cross-referenced with policy documents and media reports. Participants were provided with summaries of their statements for validation.

Ethics statement

Ethical considerations were central to this research. Participant identities were anonymised and interview recordings and transcripts were securely stored. Informed consent was gained from all participants before interviews commenced. Clear explanations regarding the purpose of the study, voluntary participation and the right to withdraw at any stage was provided. Ethics approval was granted by the Auckland University of Technology (#23/278).

Results

Three key themes emerged from the data analysis:

- coordination and collaboration

- challenges in training and communication

- the importance of building relationships.

Coordination and collaboration

Ninety per cent of the participants emphasised the critical importance of a swift response effort. While emergency services organisations rapidly mobilised teams to the affected regions, one-third of participants described the initial operations at the emergency coordination centre as ‘disorganised’ or ‘chaotic’. Perceived confusion regarding roles and responsibilities was seen to have contributed to inefficiencies in response activities. This lack of clarity may have led to duplicated situational assessments and delays in mobilising critical resources:

Overall, the coordination did work, but I think it took a lot of effort and a lot of people to make it work. It could have been a little bit more efficient if there'd been a clearer definition of ‘this is your job’ and ‘this is what you do’, and people stuck to that a bit more, and so a lot of what we were doing was having to negotiate that with other agencies along the way so that we were clear that's your job, this is our job.

(PM11, 07/02/2024)

I think the story of how every organisation turned up with the same piece of paper asking for the same information might say there were some issues, for sure. I think when it came to the showgrounds, I think different organisations have different priorities and different mandates, and sometimes those were conflicting. They struggled to be able to get some of their supplies out as well as they would have liked, I think.(PM04, 05/02/2024)

These challenges illustrate the complexities of collaboration during response operations and the difficulties of aligning efforts towards common objectives. Interviews revealed that some responding organisations lacked adequate preparedness, which led them to resort to ad hoc decision-making during the crisis. The absence of a Common Operating Picture and underdeveloped inter-agency relationships impeded coordination and resulted in miscommunication, role ambiguity and delays in decision-making:

There were huge gaps because there was no playbook for planning, preparedness and about coordination. The response was appalling because despite New Zealand being flood prone, there was no standardised guidelines for agencies to respond.

(PM15, 22/02/2024)

Cyclone Gabrielle aftermath, Eskdale, Hawke’s Bay - silt deposition and flood damage across orchards in the Esk Valley.

Image: Unsplash, free to use under Unsplash License (https://unsplash.com/photos/pv-SuZjqXNs), photo by Leonie Clough, February 2023.

Participants felt that significant role confusion among agencies in the early response phase hindered situational awareness and collaboration. Despite these challenges, participants emphasised the need for coordinated efforts across government, non-government organisations and community stakeholders. Some effective inter-agency cooperation was evident as reflected in the following examples:

FENZ came and dropped off one of their tents, one of their major incident tents, and that was here for a few months. There was lots of connection with Tai Whenua, the iwi, civil defence obviously at that time.

(PM05, 06/02/2024)

We were very much involved with local Māori leadership. As I mentioned, we were directly involved in [removed name] Marae. And that was really a positive response. And so, we were coordinating with them extensively. And there was, I believe, in those, so yes, we were coordinating with several other churches and so leadership at that level. And in some cases, I saw some good coordination between those church leaders and other government and non-governmental leadership.

(PM02, 19/01/2024)

Rural Advisory Groups (RAGs) provide local councils with a rural perspective on issues affecting rural communities. However, this study found that welfare staff from local government and partner community service organisations (e.g. Red Cross, Salvation Army, iwi-based providers) often lacked an understanding of rural needs and failed to involve advocacy groups such as the RAG to bridge this knowledge gap. For example, animal welfare efforts prioritised domestic pets over livestock, which are vital to farmers' livelihoods. Additionally, connections to rural support and health networks were weak compared to previous emergency events. Both the welfare and logistics functions operated sub-optimally. Logistics personnel initially assessed the needs of isolated communities and later informed welfare providers (already in contact with those communities) that needs like food, medical aid and agricultural support could not be met. This was perceived to be due to insufficient resources, logistical constraints and an inadequate initial assessment of community needs. This contributed to unrealistic expectations among affected communities (e.g. assumptions of immediate delivery of supplies) and consequent gaps in service delivery. One-quarter of the participants from government organisations stated it was difficult to meet the needs of affected people:

I think there's still a gap... disasters are just so huge and they are so complicated... it continues to be hard to... make a guarantee that everybody's requirements are met. (PM09, 06/02/2024)

New Zealand Emergency Management Assistance Team temporary treatment tents established in Hawke’s Bay, February 2023. Image: Todd Miller

The distribution centres involved staff from the Ministry of Civil Defence Emergency Management, New Zealand Defence Force, and iwi and volunteers to dispatch supplies to Hawke’s Bay’s most remote and affected communities. This provided communities with water, food, baby products and generators. Several key informants noted that the planning for distribution centres was unclear and could have benefited from greater delegation at community and marae levels. A decentralised model of aid distribution may have ensured alignment with community-specific needs. The aid packages distributed to people did not adequately cater to the distinctive needs of different communities and demographics such as eldercare facilities and rest homes, remote communities, migrants and refugees and people dependent on regular medications, medical equipment or ongoing treatment. This was partly due to inadequate coordination and duplication of effort. While participants recognised the importance of tailoring aid to these groups, they also acknowledged the logistical and financial challenges of providing highly customised supplies during large-scale emergencies where speed and resource constraints often limit flexibility:

One of the things that was quickly realised as well, but took a bit longer to sort out, was that when it comes to food, what do you call it, when you make up a box for a family and then deliver that box 2 days in a row, there'll be overlap of items that aren't needed. For example, female sanitary items or diapers or baby formula. Those were put into boxes and then at the end of the day at the community hubs you might have loads of pads or something like this that just weren't needed because people didn't need them at that point in time…. And then dry goods and stuff like this. Some of it was desperately needed and then after a while it wasn't so much, and they were looking for other things. They didn't really want or need a stranger's donation (clothes). So, they've got all their clothes, they've got all their stuff. What they needed was something else. It's fuel, it's some staples, but no clothes.

(PM04, 05/02/2024)

During the response to Cyclone Gabrielle, the Group Emergency Coordination Centre established geographic zones with hubs where communities could gather to provide services to isolated communities in the region, rather than relying on the established marae network. One of the participants from a marae noted that Māori leaders and communities found themselves facing significant frustration regarding the zoning strategy. The zoning approach was intended to divide the disaster response efforts into manageable sections, each overseen by a designated team. The rationale behind the zoning strategy was not explicitly detailed in participant interviews, however, it is possible that factors such as infrastructure (e.g. proximity to main roads, emergency facilities or helicopter landing sites), access constraints (e.g. road access, river crossings or terrain challenges) or logistical efficiency influenced the decision (e.g. ease of coordinating aid distribution).

However, these considerations did not always account for the established networks, governance structures and traditional land divisions of Māori communities, leading to inefficiencies in aid distribution and challenges in coordination. Furthermore, this approach created confusion among Māori wardens and iwi liaisons. Māori wardens play a key role in supporting local communities: they provide cultural leadership, help whānau access critical services and resources, offer advice, coordinate with disaster response organisations and are often among the first on site during an emergency. Poor communication regarding the zoning strategy disregarded the established expertise of mana whenua [Māori who have cultural ties to the land] who felt under-valued in the response efforts. These inconsistencies between external assistance and local cultural norms hindered an effective response in the region:

The challenge with Civil Defence was that they had military and too many people from out of town here, so they didn't understand culturally how to respond.

(PM05, 06/02/2024)

Challenges around training and communication

The findings revealed that both volunteers from Volunteer Hawke’s Bay and staff from Civil Defence Emergency Management lacked adequate training in CIMS, posing a significant challenge in responding to a large-scale disaster. A lack of training was most evident in participants’ limited grasp of how the intelligence, welfare and logistics functions interrelate, which affected operational cohesion. It was not only volunteers but also staff who struggled to understand the interconnections between key functions. This lack of familiarity with CIMS hindered the completion of critical tasks, ultimately affecting the overall effectiveness of the response. A significant discrepancy emerged between those who were confident in using CIMS and those untrained or unfamiliar with its structure, which created operational disconnects:

I witnessed firsthand multiple people who are employed in civil defence, councils and government, full-time basically losing their mind within that first day because they were just completely unprepared for what was going to happen. And yeah, they were just overwhelmed, it was really, it was sad because, you know, when the wheels start to fall off within the centre, you can only imagine, like if we can't get our crap together in the centre, there is no way that we're providing the support that our community needs. Yeah, that's true.

(PM06, 06/02/2024)

So, obviously, CIMS is the framework, CIMS is the guidance, but again, unless you're CIMS trained or have some experience operating within a CIMS structure, you're left unmoored, like you just, you don't have that framework. It's that if you're CIMS trained and if you've worked in this space for long enough, the structure is a very inherent part of your job. You just know it, and you just do it. But because, you know, even the council staff and whose job description says they might need to come and do this stuff, I would say 95% of them aren't trained in that they wouldn't understand that framework or structure and didn’t know where to go and how to perform.

(PM06, 06/02/2024)And definitely just getting our own sort of staff up to scratch with CIMS training and response and exercising the different types of scenarios that we might be in, whether it be flood or volcanic activity or an earthquake.

(PM03, 19/01/2024)

A key challenge in the disaster response was inadequate communication between emergency operations centres (responsible for coordinating response activities at the local or district level) and other agencies during the initial phase. About 80% of interviewees reported difficulties accessing information due to widespread technology failures including cellular network outages, unreliable radio systems and delayed updates from response agencies. These communication breakdowns significantly undermined the effectiveness of the overall response:

Certainly, there was communication gaps physically with cell phones being down. We operate a lot of our systems via a cell phone or via the cell phone network. Not our radios. We could use our radios, but they don't work terribly well in wet [conditions]. So, contacting staff on the ground was sometimes difficult. Not only that, but you can imagine the noise and the conditions they’re working in. So, you know, there were probably equipment failures or people were going into deep water with a radio that was then broken, you know and things like that. So, we had communication issues with our staff.

(PM08, 06/02/2024)

In instances where communication technologies failed, there was a lack of alternative or contingency communication options. Some participants suggested that solutions such as Starlink could be beneficial, as it remains operational during telecommunication breakdowns. Three-quarters of respondents from government organisations also noted that siloed communication flows made it difficult to assess needs and allocate resources efficiently:

It wasn't so much the information gap that was the problem. It was the use of the information that we did have. So, the decisions that were made based on the information that we had. Once the comms went down, we lost telecommunications, we lost power, we lost everything. Once that happened, we then didn't have any information. So, we were making poor decisions based on poor information.

(PM06, 06/02/2024)

Most participants mentioned the absence of regular communication among organisational leadership. This included a lack of routine meetings, incident boards and the absence of a unified system for information sharing, such as a Common Operating Picture and consistent documentation. Additionally, they highlighted the absence of a standardised process for coordinating updates, as interviewees noted:

So, I would say like in terms of receiving information, like the biggest challenge was just that like communication and sharing of data was a bit of a challenge during the whole event.

(PM13, 14/02/2024)

They were doing that as well during the response, I know that, and right at the start, but their tie-in to civil defence just wasn't that good, and how they could share that information and the intelligence and the coordination of that with civil defence wasn't there really. And that was just a critical issue with that system.

(PM04, 05/02/2024)

Poor communication led to the creation of numerous action plans, situational reports and communications, many of which were contradictory, overlapping or inconsistently shared among response teams. This lack of coordination caused confusion, misalignment in decision-making and delays in response times.

Critical role of building relationship with organisations

The final theme that emerged from the interviews was the need to build or strengthen relationships among response actors (both formal and informal). Cyclone Gabrielle posed significant challenges for those involved in the response including government agencies, non-government organisations and marae. These challenges contributed to strained relationships and some participants expressed resentment due to a perceived lack of support or feelings of neglect caused by bureaucratic processes during a period of severe distress. Three-quarters of the interviewees believed that an opportunity was missed in the early response phase to leverage regional networks and activate existing relationships more effectively:

The Ministry of Social Development Regional Commissioner, who leads government agencies in the region, was poorly connected to local Emergency Operations Centres and Group Emergency Coordination Centres. However, the ministry's 6 service centres, strong relationships with local marae, Waka Kotahi, the Ministry of Education, Te Whatu Ora and Te Puni Kokiri could have helped address challenges faced by the Group. These relationships could have aided in addressing public health issues.

(PM09, 06/02/2024)

Marae demonstrated their capacity to rapidly organise and accommodate large groups and serve as vital community hubs during Cyclone Gabrielle. They played a crucial role in supporting affected communities by providing shelter, food, hygiene facilities and by efficiently coordinating relief distribution. However, iwi, Māori organisations and marae were not systematically integrated into a formal disaster response framework. Many Māori organisations and marae felt that their well-established capabilities in delivering large-scale welfare services were overlooked or hampered by centralised bureaucratic processes:

In the early phases in the coordination centre, Iwi representatives were not included in an inclusive manner, because they should be the conduit to talk to their community. They felt they demonstrated, or they explained to me that they felt like they were put in a corner in an office out of the way and were not included in the response. So, Coordination Centres need to continuously work on how they engage with Iwi, and how they create a safe and inclusive environment. And Māori did not feel included or safe in those early phases.

(PM01, 12/01/2014)

Interviewees reflected on the critical importance of cultivating trust and strengthening relationships prior to emergencies and disasters. Several participants highlighted that proactive engagement, rooted in mutual respect and cultural understanding, was fundamental in improving the effectiveness of response efforts:

And trust comes through relationship. Relationship with emergencies is absolutely key. So, when I'm talking about breaking down those silos, we need to be breaking down those silos now, not when the next cyclone occurs. And so, I think that that's something for us to learn. It's also something for NEMA to learn and CDEM groups and so on. We need to know our communities. Yeah, preparedness is key. And again, these are mantras of mine. But I believe that in emergencies, we can plan for.

(PM02, 19/01/2024)

There needs to be a constant building and maintaining of relationships, which is a two-way street, I guess, because Civil Defence needs to be a better resource to have people out in the community identifying community leaders all the time, identifying Civil Defence centres all the time and then talking to those communities to make sure they know where to go from there. But that also requires the community to prioritise that too.

(PM12, 07/02/2024)

Despite these challenges, interviewees emphasised the resilience and adaptability of most organisations involved in disaster response. Participants recognised the need to harness diverse capabilities through inclusive planning and community-driven approaches. Participants unanimously acknowledged that all actors possessed valuable capacities, however, the primary challenge lay in effectively mobilising these resources and skills during a response. There was broad consensus on the need to remain open to new ideas and the critical importance of community involvement in strengthening crisis response efforts.

Residential property damage following Cyclone Gabrielle, Eskdale, Hawke’s Bay, February 2023.

Image: Unsplash, free to use under Unsplash License, https://unsplash.com/photos/jvPQqn_dsC4. Photo by Leonie Clough, February 2023.

Discussion

Rural communities are generally portrayed as both vulnerable and resilient in the face of disaster. They are characterised by weak infrastructure, limited access to information, reliance on natural resources for livelihood and food, lack of trust in government plans and decisions and limited access to essential services (Vasseur et al. 2017). On the other hand, they often rely on strong local and historical knowledge and social support systems to deal with daily needs and times of hardship. During Cyclone Gabrielle, rural communities in the Hawke’s Bay region faced significant challenges due to loss of telecommunications, major infrastructure damage, destroyed housing, compromised power and water access and disruption to food and fuel that affected communities for an extended period. Despite such challenges, local communities were not passive but quickly organised to deal with the situation. Community hubs such as marae, schools and churches played a critical role in the response by facilitating resource distribution, disseminating information, hosting displaced people and providing emotional support.

This study confirmed a high level of local mobilisation and volunteering during response efforts. Local knowledge and relationships were invaluable for understanding and supporting communities both during and after the disaster. Māori wardens, iwi and marae were crucial in connecting responding agencies and leaders (i.e. through logistic, communication, situational awareness, contextual knowledge), thereby strengthening community relationships.

The emergency and disaster literature has increasingly emphasised that local communities generally self-organise and volunteer during disasters (Gaillard et al. 2019). For example, in the aftermath of the 1931 earthquake in Hawke’s Bay, ‘spontaneous’ volunteers were actively involved in search and rescue, debris clearance and reconstruction efforts (Hill and Gaillard 2013; MCDEM 2019c). Māori communities have historically employed a range of mechanisms and strategies to cope with emergencies and disasters. Recent examples include the 2010 Christchurch earthquake (Kenney and Phibbs 2015), the 2016 Kaikōura earthquakes (Carter and Kenney 2018) and the 2017 Edgecumbe flood (MCDEM 2019c). Marae opened their doors to both Māori and non-Māori, providing shelter, distributing food and offering emotional support to those affected.

Although communities rapidly self-organised and were active in the aftermath of Cyclone Gabrielle, there was a need for stronger system and support structures from external organisations. This study suggests that responding agencies generally mobilised quickly despite facing immense challenges of power outages, communication breakdown and infrastructure damage that hindered their ability to deliver aid and coordinate responses efficiently. Many responders highlighted high levels of stress, anxiety and a feeling of being overwhelmed by the scale of the situation. Results showed that a major challenge was the difficulty in accessing remote and isolated communities. The study found that, in some situations, there was a lack of understanding of rural needs, under-utilisation of RAGs, limited connections to rural assistance and health care systems and weak planning related to the establishment and operationalisation of distribution centres. Additionally, poor coordination between local authorities, community networks and marae hampered the effective delivery of aid. This led to delays, unequal access to essential resources and challenges in reaching vulnerable populations, particularly those in remote areas. Laking et al. (2024) pinpointed issues of resource allocation, stressing that, ‘Some communities felt that Iwi-led initiatives, where available, were more responsive and could rally action and support that government agencies did not offer’ (p.143).

The widespread telecommunications failure during Cyclone Gabrielle had profound effects on the coordination of response activities and the ability to maintain situational awareness across the region. While the Civil Defence Emergency Management Act 2002 (CDEM Act)2 requires Civil Defence Emergency Management (CDEM) groups to maintain communication and coordination during emergencies, the implementation of resilient communications infrastructure varied significantly. Within the Hawke’s Bay CDEM Group, coordination centres were equipped with satellite communications, including Starlink, aligning with good practice and expectations. However, these capabilities were not consistently mirrored across partner agencies nor extended to community-level hubs such as marae and rural community points, many of which served as de facto coordination or welfare sites during the response. The disparity in access to satellite communication infrastructure contributed to an operational disconnect between central coordination points and community-led efforts. This limited the flow of critical information and delayed the identification of needs in isolated areas. This gap highlights the need for an inclusive and integrated approach to telecommunications preparedness that extends beyond CDEM facilities to encompass all key actors within the emergency response network. Ensuring interoperable and redundant communications systems that are available and functional across all levels of response is essential to meet the legal obligations of the CDEM framework and the operational realities of distributed, community-driven response environments (Danaher et al. 2023).

In the years preceding Cyclone Gabrielle, the Hawke’s Bay region transitioned to a centralised and regionalised emergency management model under the Hawke’s Bay CDEM Group. This shift, articulated in the 2014–2019 Group Plan, emphasised integrated planning and regional coordination and positioned the Group Emergency Management Office as the central hub for capability development, governance and operational oversight (Hawke’s Bay Civil Defence Emergency Management Group 2014). However, this centralisation relied heavily on a small number of dedicated emergency management personnel, supplemented by multi-agency staff, volunteers and local authority staff whose primary responsibilities lay outside of emergency functions. While the plan identified workforce capability and interoperability as strategic priorities (e.g. BMC1-BMC5), evidence suggests that implementation was inconsistent across the region.

The independent review of Cyclone Gabrielle (Bush International Consulting 2024) highlighted the consequences of this structural shift, noting that Napier Council’s ability to maintain basic functionality was compromised during the event. The review concluded that the council had not met its statutory obligation under Section 64 of the CDEM Act to fully function in an emergency, attributing this to a lack of investment in local capability and institutional knowledge. Although not formally described as a disestablishment, the progressive de-emphasis of local-level response capacity in favour of regional integration had a tangible effect. These pre-existing structural conditions characterised by centralisation, under-resourcing at the local level and uneven capability development directly influenced the region’s ability to respond cohesively and adaptively as Cyclone Gabrielle unfolded.

This study identified communication and coordination challenges between Māori wardens and iwi liaisons and response agencies. This led to a lack of recognition of Māori community service skills and the under-utilisation of their expertise in response efforts. Additionally, the lack of coordination with marae staff in response initiatives limited their ability to contribute effectively, despite their cultural knowledge and community leadership. Participants felt that this lack of inclusion may have weakened coordination efforts, reduced the effectiveness of culturally responsive strategies and overlooked valuable local resources essential for disaster response. These findings match with the post-Cyclone Gabrielle government report, which noted that marae capacities and Māori expertise were ‘either ignored or hampered by bureaucratic decision-making’ (Bush International Consulting 2024, p.6).

Researchers, practitioners and policymakers have increasingly emphasised that the systematic incorporation of Māori leadership and marae networks in emergency management frameworks is paramount to disaster resilience (Kenney et al. 2015; MCDEM 2019c). A key objective of the National Disaster Resilience Strategy is to ‘Build the relationship between emergency management organisations and iwi/groups representing Māori, to ensure greater recognition, understanding, and integration of iwi/Māori perspectives and tikanga in emergency management’ and to ‘enable and empower community-level response, and ensure it is connected into wider coordinated responses’ (MCDEM 2019c, p.3). However, this study indicates that, in practice, substantial gaps remain.

By 2023, most CDEM groups in Aotearoa New Zealand had formally included iwi partners in their respective group plans and governance arrangements, reflecting commitments articulated in the Coordinated Incident Management System (CIMS), 3rd edition (MCDEM 2019b)that explicitly emphasises the need for iwi inclusion in emergency readiness and response. In the case of the Hawke’s Bay CDEM Group, the operative 2014–19 Group Plan acknowledged the importance of building relationships with iwi and hapū [sub-tribes] as part of enhancing community resilience and capability. However, the practical implementation of this objective appeared limited. While formal mechanisms for iwi representation existed through the Coordinating Executive Group and advisory networks, this study did not find strong evidence of deep or sustained engagement with iwi in decision-making or planning processes prior to Cyclone Gabrielle. This lack of proactive integration may have constrained opportunities to fully harness the leadership, networks and cultural expertise of iwi. The absence of embedded iwi roles within coordination structures, despite policy guidance and national strategy, represents a critical contextual gap that shaped the character and effectiveness of the regional response effort.

Another significant challenge involved the inconsistent understanding of CIMS among emergency management personnel. Specifically, CDEM staff and volunteers from Volunteer Hawke’s Bay demonstrated inconsistent training, limited operational experience and difficulty comprehending CIMS functions such as intelligence, logistics and welfare. Additionally, responders lacked clarity on the leadership responsibilities necessary for inter-agency coordination and often struggled to adapt to rapidly shifting operational demands. This gap was explicitly identified in the Government Inquiry into the North Island Severe Weather Events (New Zealand Government 2024, p.53), which called for comprehensive reform of the emergency management system and emphasised the need for staff to be ‘appropriately trained and well-versed in the CIMS framework’. This study supports this recommendation, suggesting that all personnel likely to be involved in emergency response should receive regular training and participate in exercises to build operational confidence and develop proficiency within coordination centres, including iwi and marae.

The use of incident command systems such as AIIMS and CIMS reflects an effort to systematise the coordination of multiple organisations during emergencies and disasters. However, critics argue that these frameworks are often ill-suited to the complexity of contemporary disaster environments. Their reliance on rigid hierarchies and linear coordination processes can hinder adaptability in fast-evolving and unpredictable situations and they often lack the contextual flexibility required to respond effectively to diverse local conditions (Comfort 2006). Although CIMS has undergone revisions (2nd edition in 2015 and 3rd edition in 2019) in response to significant events such as the 2010 Pike River mine explosion, the 2011 Canterbury earthquakes and the 2017 Port Hills fires, it continues to rely on a centralised, command-and-control structure that struggles to accommodate emergent, decentralised decision-making in high-complexity contexts (Abbas and Miller 2025). Findings from this study suggest that CIMS may lack the necessary flexibility to respond effectively in dynamic disaster contexts. It appears to fall short in accommodating actors such as volunteers that often play crucial roles in response (Burke 2018). These insights point to the need for a re-evaluation of incident command frameworks to ensure they are sufficiently flexible and capable of adapting to complex, fast-evolving situations (Miller et al. 2025).

Nevertheless, it is important to recognise the considerable advances embodied in CIMS (3rd Edition), particularly the emphasis on flexibility and inclusivity. Compared with earlier iterations, CIMS (3rd Edition) represents a significant evolution in design and intent including greater emphasis on flexibility, scalable coordination and inclusive engagement across national, regional and local actors. Its principles explicitly support devolved decision-making, context-specific adaptation and recognition of non-traditional response partners including iwi, community organisations and spontaneous volunteers. However, the findings from this study suggest a substantial gap between the framework’s intent and its operationalisation in practice. Despite the structural improvements in CIMS (3rd Edition), response agencies appear to revert to hierarchical and rigid coordination mechanisms under pressure and struggle to adapt to the scale and complexity of the event. Limited prior engagement with communities and partners means that the necessary trust, understanding and pre-established roles on which CIMS flexibility relies are not in place. This disconnection between policy and practice illustrates a key learning: the effectiveness of progressive frameworks like CIMS depends not only on their structural content but also on the depth of institutional readiness, cross-agency familiarity and relational capacity developed before a disaster occurs.

Conclusion

This study assessed the effectiveness of the Cyclone Gabrielle response in Hawke’s Bay, addressing the critical question of how coordination between government agencies, iwi and community actors influences disaster outcomes. The research revealed systemic challenges in communication, decision-making and inclusion of Māori and local leadership, while also demonstrating the strengths of community self-organisation, cultural networks and volunteer mobilisation.

To address these limitations, several measures are recommended. First, CIMS should incorporate flexible coordination models that promote decentralised decision-making and adaptability in complex and uncertain situations, such as when isolated rural communities must initiate and manage their own response efforts in the absence of timely external support due to communication outages or access constraints. Second, the formal inclusion of non-traditional responders such as iwi organisations, rural advocacy and support groups and volunteers should be operationalised through clear conventions and designated liaison roles within coordination centres. Third, relationship-building must occur well before disaster events. This includes joint training and preparedness exercises that foster trust and familiarity across the sector.

This study showed that Māori wardens and iwi liaison officers, despite their deep community connections and cultural authority, were often sidelined during response operations or brought in too late to influence decisions. A more proactive approach would involve establishing clearly defined roles for Māori wardens within CIMS, developing formal induction processes to support iwi leader participation in emergency coordination centre operations and sustaining relationship-building activities outside of disaster events.